Religious Beliefs of Ancient India

Published on: 03-Oct-2024Religious Beliefs of Ancient India

Origin:Evolved over 3000 years with influences from Indus Valley and Aryans.Main Belief:Polytheistic; belief in Brahman as the ultimate reality.Sacred Texts:Vedas; Upanishads; Bhagavad Gita; Ramayana; Mahabharata.Major Deities:Brahma; Vishnu; Shiva; Lakshmi; Ganesha; Parvati.Concept of God:Trimurti (Brahma; Vishnu; Shiva) and the idea of avatars.Religious Practices:Puja; yoga; meditation; temple rituals; sacrifices.Social Structure:Caste system; role of women; religious festivals.Reincarnation:Belief in the cycle of birth; death; and rebirth (Samsara).Other Religions:Jainism; Buddhism; Tantrism; Shramana movements.Hinduism did not originate from a single founder, a single book or a single point at one time, unlike other religious traditions. It contained many different beliefs, philosophies and viewpoints, which were not consistent with each other. The Hindu insight claims that the Oneness expresses itself in many different forms. Hinduism is often labelled as a religion, but actually it is a vast and complex socio-religious body which, in a way, reflected the complexity of Indian society. This religion focused primarily on fulfilling the sexual and other desires of men rather than finding the meaning of life and discovering the creator. That is why even their religious temples contained more images of naked women and their rituals consisted of eroticism and vulgarism rather than modesty and piety. Since their religion treated women as inferior beings and as tools, women were not respected in the ancient and even some contemporary Hindu societies as well.

At first sight, Hinduism appeared to be a polytheistic religion, meaning that its followers believed in many gods. Some people estimated the number of Hindu gods to be in thousands. However, several Hindu Scholars claim that at the heart of Hinduism was really only one true ‘God’— Brahman. Brahman was also called the One, the Ultimate Reality, and the World Soul. The many gods traditionally found in Hinduism really formed part of Brahman. 1 Indologists, who study the language, culture, and history of the Indian subcontinent, have theorized that the major complexity was developed in Hinduism by the merging of the beliefs and practices of two main groups—the people of the Indus Valley in India and the Aryans of Persia. 2

In academic terms the Hindu tradition, or Hinduism, was usually referred to as Brahmanism in its earlier phase, before 300 B.C., and referred to as Hinduism after that. In common usage, the term Hinduism is used for the entire span of the tradition.

For at least two reasons the Hindu tradition contains the greatest diversity of any world tradition. First, Hinduism spans the longest stretch of time of the major world religions, with even the more conservative views setting it as well over 3,000 years old. Throughout this expanse of time, the Hindu tradition has been extremely conservative about abandoning elements that have been historically superseded. Instead, these elements have often been preserved and given new importance, resulting in historical layers of considerable diversity within the tradition. Second, Hinduism has organically absorbed hundreds of separate cultural traditions, expressed in as many as 300 languages. As a result, Hindu tradition is metaphorically like the Grand Canyon gorge, where the great river of time has sliced through the landscape, leaving visible successive historical layers.

Some practices of Hinduism must have originated in Neolithic times (4000 B.C.). The worship of certain plants and animals was sacred, for instance, could very likely have very great antiquity. The worship of goddesses, too, a part of Hinduism today, may be a feature that originated in the Neolithic. 3

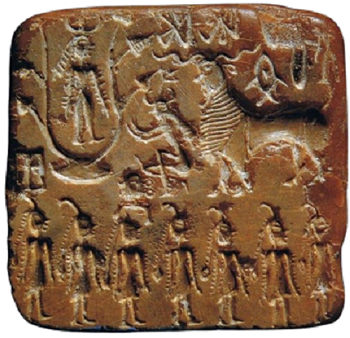

There are several artifacts that suggest religious practices similar to those found in later South Asian traditions. First, there were numerous terra cotta figurines of a female with wide hips, prominent breasts, and an elaborate headdress. Scholars speculate that this image may be a goddess associated with human and agricultural fertility. Second, there are images of animals, some natural and others mythical, on small clay seals. One seal depicts a human figure standing in a peepal tree with a row of what seem to be worshippers below. These may be precursors to the reverence for certain trees and animals found in later ages. There are also a few seals that show a figure seated in what may be a yoga posture. Finally, the great water tanks may indicate an early concern with bathing and ritual purity. 4

Hinduism is something of an umbrella term. It includes any Indian religious practice that does not claim to belong to another religion. Nevertheless, most of these religions share certain characteristics, such as acknowledging the authority of the sacred texts known as the Veda.

According to traditional European scholarship, the religion of the Veda was brought to India about 1500 B.C. The practices that we know the most about, were elaborate public sacrifices sponsored by wealthy patrons and performed by priests. Some parts of the Veda give evidence of what may have been more popular practices: spells and incantations used for medical purposes.

Starting perhaps around 600 B.C. speculation on the Veda gave rise to philosophical texts known as the Upanishads. Somewhat later more practically oriented scholars systematized the Hindu way of life in Smritis or Dharamasatras, the most important of which was the Laws of Manu. Over many centuries mythological material developed into a body of literature known as Ithihasa Purana. It includes the mammoth Epic poem, the Mahabharata, and an especially revered portion of it, the Bhagavad Gita.

From A.D. 500 to 1500, Hinduism as we know it today took shape. Beginning in south India, a movement of devotion to deities (Bhakti) drew people who had supported Buddhism back to Hinduism. Hindus started to build temples to house their gods and goddesses. The orthodox schools of philosophy, especially the various forms of Vedanta, were formulated. Tantrism, a tradition of esoteric rituals, provided alternative means to release. 5

Concept of God

While deriving the concept of God, it is but natural for man to start from the world in which he lives and moves. So, the God of Hinduism, when looked at from this angle, was the Creator. However, He created the entire world, not out of nothing which is illogical, but out of Himself. After creation, He sustains it with His power, rules over it like an all-powerful emperor, meting out justice, as reward and punishment, in accordance with the deeds of the individual beings. At the end of one cycle of creation—Hinduism advocates the cyclic theory of creation—He withdraws the entire world order into Himself.

The Hindu scriptures wax eloquent while describing the qualities of God. He is all-knowing and all-powerful. He is the very personification of justice, love and beauty. In fact, He is the personification of all the blessed qualities that man can ever conceive of. He is ever ready to shower His grace, mercy and blessings on His creation. Fairly speaking, the very purpose of His creating this world is to shower His blessings on the creatures, to lead them gradually from less perfect states to more perfect ones. He is easily pleased by the prayers and supplication of His devotees. However, His response to these prayers is guided by the principle that it should not be in conflict with the cosmic law, concerning the general welfare of the world, and the law of Karma concerning the welfare of the particular individual.

The Hindu concept of God has two special features. Depending upon the needs and tastes of his votaries, He can appear to them in any form they like to worship, and respond through that form. He can also incarnate Himself amongst human beings in order to lead them to His own kingdom. And this incarnating is a continuing process, taking place whenever and wherever He deems it necessary. Then, there is the other aspect of God, as the Absolute. ‘Brahman’ is the name usually given to this aspect. It means what is infinitely big. It is the Infinite itself. It transcends everything that is created. Yet, it is immanent too, immanent in all that is created. 6

Another theory is that divinity is conceived in the Hindu framework in complex metaphysical ways. 7 It is said that fear from natural calamities was the beginning of conception of divine powers. The ancient people of India were greatly afraid of the mysteries of physical forces and phenomena which they could not understand and over which they had no control. Their faithful imagination found the interpretation of life and reality in the concept of ‘animism’ which was nothing but their belief in the existence of doubles or spirits in habituating every living or non-living being. Their animistic beliefs gradually led them to believe in the existence of super-human beings or gods and goddesses who are supposed to be living in their heavenly abode but were controlling the forces and phenomena of nature as well as human life. The ancient sages realized that the whole creation is the manifestation of Brahma or Bhuma. They believed that Brahma was the ultimate reality. Once nothing existed except this absolute. 8

The polytheism of the Hindus, has remained a mysterious riddle. It will continue to remain so until it is viewed in the right perspective. There are three aspects to this polytheism. The three main cult deities consisting of Brahma, Visnu and Siva—along with their consorts, form the first aspect. 9

The key idea here is one of a triple principle referred to as Trimurti. 10 Trimurti, in Hinduism, is a triad of the three gods Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. The trimurti merges the three gods into a single form with three faces. Each god is in charge of one aspect of creation, with Brahma as creator, Vishnu as preserver, and Shiva as destroyer. In combining the three deities in this way, however, the doctrine elides the fact that Vishnu is not merely a preserver and Shiva is not merely a destroyer. Moreover, while Vishnu and Shiva are widely worshipped in India, very few temples are dedicated to Brahma, who is expressly said to have lost his worshippers as the result of telling a lie and is merely entrusted with the task of creation under the direction of one of the other two gods. Scholars consider the doctrine of the trimurti to be an attempt to reconcile different approaches to the divine with each other and with the philosophical doctrine of ultimate reality. 11

Holy Books

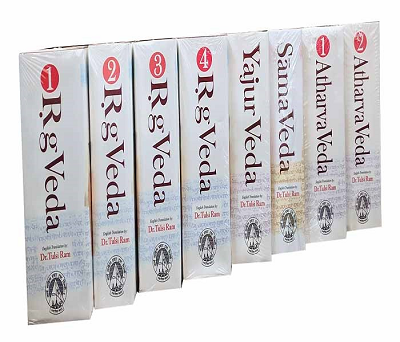

The earliest religious compositions in India are the Indo-European Sanskrit texts, the Vedas. The word Veda means knowledge, and these texts contained information necessary to the performance of sacred fire rituals. It is difficult to date the texts accurately, but scholars believe they were composed between 1500 and 600 B.C. These Vedas were preserved orally. Priestly families passed on the texts from generation to generation, using elaborate mnemonic systems to preserve them accurately.

In the most limited sense, the Vedas are four “collections” (samhitas) of ritual material. The Rig Veda Samhita contains ten books of hymns to various deities. Each of these books was composed by sages belonging to the priestly families who were responsible for preserving the hymnal lore. These hymns were recited by priests during the fire rituals. The Sama Veda Samhita is a book of songs based on the Rig Veda with instructions for their recitation. The Yajur Veda contains short prose formulae and verses, or mantras, used in ritual. The Atharva Veda is a collection of hymns and magical formulae, many of which are not related to the sacrificial ritual, but to matters of daily life. This text was the latest addition and has not been given the same status as the first three, a circumstance that has led scholars to suggest that it may reflect popular, non-Aryan traditions rather than those of the priesthood. Many of the formulae in the Atharva Veda are for ordinary concerns like curing diseases, warding off harmful spirits, and the prevention of snakebite. Each of the Vedic “collections” has three types of additional material and the wider use of the word Veda includes all of these. The first additions, which concern ritual exegesis, are called Brahmanas. The Brahmanas describe rules for the rituals and give explanations about their purposes and meanings. The second additions are called “compositions of the forest” (aranyakas), because, according to tradition, they were composed in the forest by solitary sages. The Aranyakas mostly supplement the Brahmanas, focusing on rites that were not developed in detail in the earlier texts. They also elaborate on the importance of knowing the meaning of rituals by describing the extra benefits that accrue to the ritual performer through this special information. Finally, the Upanishads, the third type of additional material, further develop the ideas of the Aranyakas by explaining the true nature and meaning of the rituals in an age when the focus was shifting away from performance and toward knowledge.

The Upanishads are the latest additions, and were probably composed between 600 and 300 B.C. Although the Vedas are revered as sacred texts, very few modern Hindus know much about them. A few hymns are recited regularly in temples and household liturgies, but the texts are primarily ritual manuals and the bulk of their contents is only studied by priests and scholars. In spite of this, they have tremendous authority in Hindu tradition. The Vedas are described as shruti, “that which was heard” by the ancient sages. The texts contain knowledge that is considered trans-human and eternal. This knowledge was revealed to the sages when they were in meditative states. In some theistic schools the Vedas are said to be authored by God, but others believe the texts are authorless. They simply exist as eternal knowledge and the Vedic rishis (“seers”) were able to “see” that knowledge and transmit it to others. 12

Indus Gods

A theme central to Indus religion appears to be a male/ female duality. The male is best seen on the Proto-Shiva seal and the numerous other examples of this god in Indus art. It is clear that this male deity is represented by the buffalo in spite of the importance of cattle in Indus life. It appears that in some contexts a simple curve of horns was used as a symbol of the great male deity.

The symbolism surrounding the male deity on the Proto-Shiva seal is exclusively animal, suggesting the use of a male god–animal relationship. The phallic objects and baetyls from some Indus sites support the reasoning behind the presence of a male deity. The female deity emerges from the figurines but perhaps most strongly from the ‘Divine Adoration’ theme, with a female inside a plant, often the object of veneration from a male in front of her. The ‘female god–plant’ symbolism complements the ‘male god–animal’ relationship as a kind of opposition. The presence of yonis emphasizes the presence of the female deity in Indus life.

The ‘Heavenly Father–Mother Earth’ seal from Chanhu-daro can be interpreted along a number of dimensions. First, it adds documentation for the male deity, outside the context of the great yogi. It also sustains the notion that the male deity is associated with the bull, in this case the gaur, and animals generally. This seal also informs us about the presence of a female deity, associated with the earth and thereby perhaps with plants. This male–female relationship carries with it a sense of the dualism found in the later notion of shakti. This is a particular form of energy that brings the male–female duality to one. In this sense the two deities may have been ultimately resolved into one supreme Indus deity. But this shakti was not something that was rendered into physical form, or not at least a form that would seem to be present in archaeological finds.

Other Indus gods

One can gather together the two great gods of the Indus Civilization as aspects of the Indus Great Tradition, but there are more representations of gods, or spirits, or god-like creatures. These are the minotaur-like creatures, half-human, half-animal, with claws on the back feet and human feet in the front, the multi-headed animals, tigers with bull horns, humans with horns, ‘unicorns’ with elephant trunks, perhaps ‘unicorns’ themselves as in the terracotta figurines from Chanhu-daro. This is the zoolatry that Marshall discusses, and constitutes what might be considered the Indus ‘Little Tradition’ or the opposing force of ‘evil’, or threat, in the Indus Tradition. 13

Gods of Hinduism

Brahma

Brahma is a divinity who makes his appearance in the post-Vedic Indian epics (700 B.C.–100 C.E.). He has an important role in the stories of the great gods in the epics and Puranas. Brahma is always depicted as having four heads. The story is told that he was once in the midst of extended austerities in order to gain the throne of Indra, king of the gods, when the latter sent a celestial dancing girl, Tilottama, to disturb him. Not wanting to move from his meditative position, when Tilottama appeared to his right, he produced a face on his right; when she appeared behind him, he produced a face behind his head; when she appeared at his left, he produced a face on the left, and when she appeared above him he produced a face above. When Shiva saw this five-headed Brahma he scolded him for his lust and pinched off his head looking upward, leaving Brahma humiliated and with only four heads. He did not attain the role of king of the gods. There are a great many stories about Brahma in Indian mythology. Most commonly he is known as a boon giver who was required to grant magical powers as a reward for ascetics, whether animal, human, god, or demon. Often these beings, ascetics, gods, and the like would become problems for the gods when they became too powerful. 14

Agni

Since the religion of the Rigveda was mainly sacrificial, Agni, the god of fire, naturally got the pride of place. A maximum number of hymns are devoted to describing and praising Agni. He is often eulogized as the supreme god, the creator, the sustainer, the all-pervading cosmic spirit. All other gods are his different manifestations. He manifests himself as fire (Agni) on this earth (Prithvi), as lightning or air (Indra or Vayu) in the sky (Antariksa) and as the sun (Surya) in the heavens (Dyuloka). He acts as a mediator between men and gods by carrying the offerings of men to gods. He is all-knowing and all-powerful. He is all-merciful too. Though an immortal, he lives among the mortals, in every house. He protects them by dispelling their difficulties and giving them whatever they pray for. Without him, the world can never sustain itself.

In later literature, Agni is described as the lord presiding over the southeast quarter. The image of Agni in temples, represents him as an old man with a red body. He has two heads, a big belly and six eyes, seven arms in which he holds objects like the spoon, ladle, fan etc., seven tongues, four horns and three legs. He has braided hair, wears red garment as also the Yajnopavita (the sacred thread). He is attended on either side by his two consorts, Svaha and Svadha. The smoke is his banner and ram, his vehicle. Obviously, this is an anthropomorphic representation of the sacrificial fire. 15

Contrary to the mentioned beliefs of Hinduism about Agni, if we see the details critically, fire (Agni) does not have its own existence without the help of other things like gas, wood, coal etc. Whatever material is required to burn the fire, it comes out from the sand of the earth directly or indirectly. Additionally, fire always burns others including its believers and their belongings.

Shiva

Shiva is a principal deity of Hinduism who is especially revered among the cluster of Hindu groups known as Shaivites. He is widely worshipped by Hindu communities throughout India and the world. Shiva is an ancient Hindu deity that is associated with the paradoxical motifs of destruction and regeneration, eroticism and asceticism, sexuality and celibacy. Hindu religious iconography and mythology simultaneously describe him as a great ascetic as well as co-generator of the universe along with Shakti (the female principle of creation). 16

Shiva is often connected with the Vedic god Rudra (the howler) who is portrayed in the Rig Veda as an outsider god and lord of animals. As befits his powers, Shiva is often portrayed smeared in ash. He dresses in leopard skin and holds a trident with a small drum; a cobra is wrapped around his shoulders and the river Ganges emanates from his matted locks. He is most commonly represented sitting in yogic posture, emphasizing his association with renunciation and asceticism.

Shiva was a god of opposite; he was a fierce ascetic but also prone to sexual excess and anger. The central image of Shiva was a shaft or elongated oval called the linga. In one myth of origin of the linga, Brahma and Vishnu were arguing about who was the supremem creator of the universe. As the two gods continue their dispute, a gigantic shaft or linga of burning light appears. As Brahma and Vishnu unsuccessfuly attempt to span its height and depth, the linga opens to reveal Shiva inside. In this sense, the linga represents a kind of cosmic energy with Shiva as the supreme god who creates, sustains, and destroys.

In other myths, the power of Shiva’s linga is unmistakably sexual. After disturbing the wives of sages in the Pine forest, Shiva is castrated and the universe loses its vital powers and begins to wither and die. In this sense, the linga represents sexual generativity, and Shiva is often presented with an erect penis – a sign not of promiscuity, but of creativity and power. As an ascetic, Shiva holds his sexual power in check and thus overcomes and transmutes the power of passion for the benefit of the cosmos. For images of Shiva used for worship, the oval linga is often represented joined with or penetrating the circular yoni or vulva. The linga and yoni together represent the union of Shiva and Shakti, the masculine and feminine elements in creation. 17

Parvati

Parvati (daughter of the mountain) also called Uma, is considered the wife of Shiva. 18 Parvati, the mountain goddess, is an aspect of the great mother goddess devi. As Parvati, the daughter of Mena, who was married to Himavat, the god of the Himalayans, she was known as the great virgin. She was the sister of the goddess Ganga who was the personification of the sacred river Ganges. Parvati’s relationship with Shiva followed Shiva’s relationship with Sati. When Sati died, the gods wanted Shiva to remarry and decided that Sati should return as Parvati. 19 She was described as virtuous, maternal, and her sexual fidelity to Shiva is never questioned. Parvati’s central purpose was to domesticate Shiva so he may enter the householder stage. Householder was one of the stages on the Hindu path to moksha, the liberation a person from the cycle of reincarnation. The Goddess Parvati teaches that a woman’s purpose was to serve her husband, care for their children and maintain the family. 20

Ganesha

Ganesha (also known as Ganesa or Ganapati) was one of the most important gods in Hindu mythology and he was also worshipped in Jainism and Buddhism. For the Ganapatya Hindu sect, Ganesha was the most important deity. Ganesha was highly recognizable with his elephant head and human body, representing the soul (atman) and the physical (maya) respectively. 21 He was the god of wisdom and eloquence, arts and letters, the remover of obstacles, the first scribe and god scribes and patron deity of literature. He was the god of science and skills, god of seductive eloquence, god prosperity, and ruler of the demon dwarfs, known as the Ganas. Numerous myths surround this popular deity. In some accounts, he was the son of Parvati and Shiva and his siblings are Karttikeya and Kumara. In other renditions, he was born from a mixture of dust and Parvati’s body moisture or the sacred water of the Ganges River. Many of his myths involve his head. Parvati was anxious to show her newborn to Shiva. His searing glance reduced the child’s head to ashes. Brahma advised her to take the first head she could find for her baby. Another myth relates that when Ganesha blocked Shiva’s path to Parvati’s bath, the angry god struck off his head. To keep Parvati happy, he replaced it with an elephant’s head. Ganesha’s head is attributed to Parvati’s wrath in another legend where she was jealous of his beauty and cursed him to be fat with an elephant’s head. 22

Kali

Kali, the consort of Mahakala, the eternal time, represents Shakti, the primordial energy, and the cause of creation, preservation and destruction of all objects of the universe, animate or inanimate. The image represents an integral vision with the inactive purasha, the conscious soul as the lord, and the nature soul as his executive energy. When the Purusha evolves itself in the action of Energy, there is creation and the enjoyment of ananda (bliss), and of becoming. Kali remains in a state of eternal bliss. She showers immense mercy on the devoted worshippers as the creative principle of the world.

Kali was described as dark-complexioned, being infinite like the vast space representing the original state of creation. The goddess was called ‘kali’ because all the three aspects of cosmic function take place in time, the Kaala. 23

Vishnu

Vishnu is one of the three great deities. 24 It fits into brahmanical philosophy very easily. Vishnu was described as a kingly god who is greatly concerned with dharma. He is irrevocably associated with avatara doctrine. It was Vishnu who enters the world in order to preserve order whenever unrighteousness threatens. The idea of successive incarnations allowed Vishnu to absorb other deities, thus bringing different religious traditions together in one system. So, for example, Vishnu incarnated as a dwarf in the Vedas to reclaim the universe from the demons who had dispossessed their gods. The number of incarnations varies from one Purana to another, but the most popular tradition gives ten avataras. Of these, Krishna and Rama, the heroes who ensure the triumph of dharma in the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, are the most widely revered.

Vishnu’s manifestation was not, however, limited to avataras. According to the Vaishnava creation story, all the deities come from Vishnu. Vishnu is Brahman, the cause and substance of the cosmos. He was both the conscious purusha and the material prakriti, the two primordial principles of Samkhya philosophy, and he is also time (kala) which brings about the connection and separation of purusha and prakriti. In the old Samkhya theory, the primordial principles were ultimately separate, but in the Puranas, they are all part of the infinite Vishnu. Creation begins when Vishnu disturbs the equilibrium of the three qualities (gunas) of prakriti, thereby causing prakriti to evolve the elements of existence. These elements come together to form a vast egg resting on the cosmic waters. Vishnu enters this world egg as the creator god, Brahma, and arranges creation. Then he takes the role of Vishnu the preserver and maintains order in the cosmos. Finally, he becomes Shiva the destroyer and dissolves his creation into a great ocean. 25

Durga

A Hindu Goddess, especially popular in eastern India. She was popular with several different names in Hinduism including Adi Parashakti, Devi, Shakti, Bhavani, Parvati, Amba etc. 26 She is usually shown with eight or ten arms that hold weapons and riding either a tiger or a lion. According to their legend, the goddess Durga was created when a powerful water buffalo demon, Mahisha, began to savage the Earth. Each of the gods tried to stop him, but they were unable to, so they decided to combine their powers into one being more powerful than any of them. Perhaps because the Sanskrit word sakti, divine power, was feminine, the being they created was female, Durga. Her images portray her defeating Mahisha. Durga is one of several manifestations of the goddess in Hinduism. She is worshiped by followers known as Saktas. Her major festival is Navaratri, observed in Bengal in the cooler time of the year just after the monsoons. It celebrates Durga's victory over Mahisha. 27

Kama

Kamadeva or Kama was the Indian cupid, the god of love. He was found in the Vedas as a divinity, but his character was developed in the Indian epics and Puranas. More popularly, Kamadeva is known to have been burned to ashes by the third eye of Lord Shiva. In that tale, Shiva was in a state of Meditation and ascetic withdrawal. The gods desperately wanted him to marry and have progeny, because they knew that his offspring would be able to defeat the demon Taraka, who was plaguing them. They sent the god of love to awaken sexual desire by shooting him with his flower arrows. Shiva became angry at Kamadeva for his presumption and he incinerated him with his third eye. Upon the mournful request of Kamadeva’s wife, Rati, Shiva relented and restored the god of love to life, but without a body. This is why he is invisible. 28

Sarasvati

Sarasvati was the Sakti, the power and the consort of Brahma the creator. Hence, she was considered procreatrix, the mother of the entire creation including knowledge, music, art, wisdom and learning. 29 Sarasvati literally means ‘the flowing one’. In the Rigveda, she represents a river and the deity presiding over it. Hence, she is connected with fertility and purification. Here are some of the names used to describe her: Sarada (giver of essence), Vaglsvari (mistress of speech), Brahmi (wife of Brahma), Mahavidya (knowledge supreme) and so on. It is obvious that the concept of Sarasvati, developed by the later mythological literature is already here. The ‘flowing one’ can represent speech also if taken in an allegorical sense. Hence Sarasvati represents power and intelligence from which organized creation proceeds.

She is considered as the personification of all knowledge— arts, sciences, crafts, and skills. Knowledge is the antithesis of the darkness of ignorance. Hence, she is depicted as pure white in colour. Since she is the representation of all sciences, arts, crafts and skills; she has to be extraordinarily beautiful and graceful. Clad in a spotless white apparel and seated on a lotus seat, she holds in her four hands a Vina (lute), Aksamala (rosary) and Pustaka (book). Though these are most common, there are several variations. Some of the other objects shown are: Pasa (noose), Ankusa (goad), Padma (lotus), Trisola (trident), Sahkha (conch), Cakra (discus) and so on. Occasionally she is shown with five faces or with eight hands. Even three eyes or blue neck are not uncommon. In this case she is the Mahasarasvatl aspect of Durga or Parvati. 30

Lakshmi

For obvious reasons, Lakshmi, the goddess of fortune, 31 was more sought after than Sarasvati, the goddess of learning. Being the power and consort of Vishnu, the preserver, she is represented as the power of multiplicity and the goddess of fortune, both of which are equally necessary in the process of preservation.

‘Sri’ or ‘Lakshmi’, as depicted in the Vedas, is the goddess of wealth and fortune, power and beauty. Though there is scope for the supposition that Sri and Lakshmi are two separate deities, the descriptions of them are so identical, that we are tempted to conclude that they represent one and the same deity. Some scholars opine that ‘Sri’ was a pre-Vedic deity connected with fertility, water and agriculture. She was later fused with Lakshmi, the Vedic goddess of beauty.

In her first incarnation, according to the Puranas, she was the daughter of the sage Bhrgu and his wife Khyati. She was later born out of the ocean of milk at the time of its churning. She, being the consort of Vishnu, is born as his spouse whenever he incarnates. When he appeared as Vamana, Parasurama, Rama and Krishna, she appeared as Padma (or Kamala), Dharani, Sita and Rukmini. She is as inseparable from Vishnu as speech from meaning or knowledge from intellect, or good deeds from righteousness. He represents all that is masculine, and she, all that is feminine.

Lakshmi is usually described as enchantingly beautiful and standing on a lotus, and holding lotuses in each of her two hands. It is because of this, perhaps, that she is named as Padma or Kamala. She is also adorned with a lotus garland. Very often elephants are shown on either side, emptying pitchers of water over her, the pitchers being presented by celestial maidens. Her color is variously described as dark, pink, golden yellow or white. 32

Elixir of Immortality

Soma (Sanskrit) or Haoma (Avestan) was a Vedic ritual drink of importance among the early Indo-Iranians, and the subsequent Vedic and greater Persian cultures. 33 This drink was composed from a plant, most likely hallucinogenic, which caused an overwhelming and empowering feeling of intoxication. This intoxication was perceived to be a quality of the gods, who were also said to consume the beverage for purposes of maintaining their immortality. Soma is praised in 120 hymns within the Rig Veda, rendering it one of the most recognized entities in that text. For example, the entirety of the Ninth Mandala of the Rigveda, also known as the Soma Mandala consists of hymns addressed to Soma Pavamana (or "purified soma"). Soma was considered to be the most precious liquid in the universe, and therefore was an indispensable aspect of all Vedic rituals, used in sacrifices to all gods, particularly Indra, the warrior god. Supposedly, gods consumed the beverage in order to sustain their immortality. In this aspect, soma is similar to the Greek ambrosia (cognate to amrita) because it was what the gods drank and what helped make them deities. Indra and Agni (the divine representation of fire) are portrayed as consuming soma in copious quantities. Soma could also bestow the power of the gods upon mortals. When consumed by humans, soma's intoxicating effect represented the temporary replacement of sensory pleasure with that of bliss, or ananda. The effects of this bliss included immortality, poetic insight, enhanched fertility, the ability to heal, the attainment of wealth, and perhaps most importantly, the ferocity of Indra. 34 Although the hymns describe soma as hallucinogenic, one need not take this literally. One can explain such visions in purely psychological terms, as induced or fostered by the priests’ heightened expectations in the sacrificial arena. 35

Four Goals of Life

Another major aspect of Hindu religion that is common to practically all Hindus is that of purushartha, the "four goals of life." 36 The four are artha 37 (prosperity, worldly well-being), kama 38 (pleasure, erotic satisfaction), dharma 39 (right conduct, adherence to social law), and moksha 40 (liberation from the rounds of birth and rebirth). 41

Other Religions

Tantrism

The Sanskrit word tantra has appeared since Vedic times 42 and is a general term for a genre of secret ritually based religious practices. These are most often laid out in texts also known as tantras (loom), so named because these texts weave a distinctive picture of reality. In popular Hindu culture, tantrikas (tantric practitioners) are associated with illicit sexuality, with consuming forbidden things such as meat and liquor, and with having the ability to kill or harm others through black magic. Such power and perceived amorality make tantrikas objects of fear, a quality that some people have used to their advantage. A more neutral assessment of tantra would stress three qualities: secrecy, power, and non-dualism, the ultimate unity of all things. 43

Jainism

Jainism is properly the name of one of the religious traditions that have their origin in the Indian subcontinent. According to its own traditions, the teachings of Jainism are eternal, and hence have no founder; however, the Jainism of this age can be traced back to Mahavira, a teacher of the sixth century B.C, a contemporary of Buddha. Like those of Buddha, Mahavira’s doctrines were formulated as a reaction to and rejection of the Brahmanism (religion based on the Hindu scriptures, the Vedas and Upanisads) then taking shape. The Brahmins taught the division of society into rigidly delineated castes, and a doctrine of reincarnation guided by karma, or merit brought about by the moral qualities of actions. Their schools of thought, since they respected the authority of the Vedas and Upanisads, were known as orthodox darsanas which means literally, ‘views’. Jainism and Buddhism, along with a school of materialists called Carvaka, were regarded as the unorthodox darsanas, because they taught that the Vedas and Upanisads, and hence the Brahmin caste, had no authority. 44

Shramana Tradition

Vedic religion of Iron Age India co-existed and closely interacted with the parallel non-Vedic shramana traditions. These were not direct outgrowths of Vedism, but separate movements that influenced it and were influenced by it. The shramanas were wandering ascetics. Buddhism and Jainism were a continuation of the shramana custom, and the early Upanishadic movement was influenced by it.

As a rule, a shramana was one who renounced the world and led an ascetic life for the purpose of spiritual development and liberation. They asserted that human beings were responsible for their own deeds and reaped the fruits of those deeds, for good or ill. Liberation from such anxiety could be achieved by anybody irrespective of caste, creed, colour or culture. Yoga was probably the most important shramana practice to date. Elaborate processes were outlined in Yoga to achieve individual liberation through breathing techniques (Pranayama), physical postures (Asanas) and meditation (Dhyana).

The movement later received a boost during the times of Mahavira and Buddha when Vedic ritualism had become the dominant belief in certain parts of India. Shramanas adopted a path alternate to the Vedic rituals to achieve liberation, while renouncing household life. They typically engaged in three types of activities: austerities, meditation, and associated theories (or views). At times, a shramana was at variance with traditional authority, and he often recruited members from priestly communities as well. Mahavira, the 24th Jina, and Gautama Buddha were leaders of their shramana orders. According to Jain literature and the Buddhist Pali Canon, there were also some other shramana leaders at that time. 45

Concept of Reincarnation

The Indian belief in the “cycle of lives” has an ancient origin. Souls are believed to cycle through human or animal lives until they are liberated and merge with a higher reality. On rare occasions the tradition refers to reincarnation into a plant or stationary object. The concept appears to have emerged in late Vedic times. Some argue that the idea was present in the Vedic tradition from the beginning, but little evidence can be found in any of the Vedic collections of Mantras, and only very occasional references are found in the Brahmanas, the explanatory portions of the Vedic collections. By the time of the Upanishads the notion of reincarnation seems to have become centrally important.

Some sects in ancient times appear to have believed that every soul must travel through a fixed number of births; one text puts the number at 8,400,000. The Ajivika sect believed that these births were all inevitable and could not be escaped; one could reach liberation only after they were all completed. Many early sects adopted extreme ascetic practices, avoiding any taint of worldly passion, in order not to add to the accumulation of Karma that had occurred from previous lives. Later Hinduism, as well as Buddhism and Jainism, made the notion of reincarnation central to spiritual and religious practice, enshrining the notions of karma and Samsara (the round of birth and rebirth) in Indian culture and practice.

In these traditions, reincarnation results from one’s actions in one’s previous life, one’s karma. 46 In the process of time one might endure a huge number of highly undesirable births; samsara, or worldly existence, was thus a trap one tried to escape. Such escape of rebirth has been the primary obsession of all practice in nearly all Indian traditions (except Islam) up to the present day. Buddhism, does teach the rebirth doctrine and asserts that living beings are reborn, endlessly, reincarnating as Devas (gods), demi-gods, human beings, animals, hungry ghosts or hellish beings. 47 Moksha or Nirvana, the liberation or release from this cycle, is the highest goal in all the major traditions.

One path was severe, world-denying asceticism. Meditative yoga was seen as another way, which allowed one’s mind or consciousness to remove itself from attachment to worldly life and thereby pave the way to liberation. Alternatively, a focus upon God could earn the grace of the divinity and God could help break the bonds of karma. Traditionally it has been said in Hinduism, too, that a true Guru can literally strip away one’s karma, and thus devotion to gurus has become a strong feature of Hinduism. 48

Most people mistakenly believe that the religion of ancient India was a universal one because at that time, Hinduism was the prevalent religion which was based on concocted myths, personal desire and lacked religious equality. Secondly, their concept of God was extremely complicated, confusing and vulgar whereas the concept of God provided by the divine messengers was simple and non-controversial. The ancient Indians chose to believe in the former and were unable to know their creator and spent their lives in misguidance.

- 1 Madhu Baaz Wangu (2009), World Religions: Hinduism, Chelsea House Publishers, New York, USA, Pg. 11.

- 2 Ibid, Pg. 18.

- 3 Constance A. Jones & James D. Ryan (2007), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. XVII.

- 4 Cybelle Shattuck (1999), Religions of the World: Hinduism, Routledge, London, U.K., Pg. 19.

- 5 Robert S. Ellwood & Gregory D. Alles (1998), Encyclopedia of World Religions, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 159.

- 6 Swami Harshananda (N.D.), Hindu Gods and Goddesses, Sri Ramakrishna Nath, Madras, India, Pg. 2-3.

- 7 Elizabeth M. Downing & W. George (2006), Encyclopedia of Religious and Spiritual Development, Sage Publications, London, U.K., Pg. 200.

- 8 Pranab Bandyopadhyay (1995), Gods and Goddesses in Hindu Mythology, United Writers, Calcutta, India, Pg. 5-6.

- 9 Swami Harshananda (N.D.), Hindu Gods and Goddesses, Sri Ramakrishna Nath, Madras, India, Pg. 4.

- 10 Elizabeth M. Downing & W. George (2006), Encyclopedia of Religious and Spiritual Development, Sage Publications, London, U.K., Pg. 200.

- 11 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/topic/trimurti-Hinduism: Retrieved: 01-03-2018

- 12 Cybelle Shattuck (1999), Religions of the World: Hinduism, Routledge, London, U.K., Pg. 20-21.

- 13 John R. Hinnells (2007), A Handbook of Ancient Religions, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., Pg. 481-482.

- 14 Constance A. Jones & James D. Ryan (2007), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 89.

- 15 Swami Harshananda (N.D.), Hindu Gods and Goddesses, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Madras, India, Pg. 7-8.

- 16 New World Encyclopedia (Online): http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Shiva: Retrieved: 01-03-2018

- 17 Yudit Kornberg Greenbag (2008), Encyclopedia of Love in World Religions, ABC-Clio, Oxford, U.K., Vol.1, Pg. 572.

- 18 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/topic/Parvati: Retrieved: 02-03-2018

- 19 Charles Russell Coulter & Patricia Turner (2000), Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities, Routledge London, U.K., Pg. 374.

- 20 Mary Zeiss Stange, Carol K. Oyster & Jane E. Sloan (2011), Encyclopedia of Women in Today’s World, Sage Publications Inc., London, U.K., Vol.1, Pg. 1216.

- 21 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): https://www.ancient.eu/Ganesha/: Retrieved: 02-03-2018

- 22 Charles Russell Coulter & Patricia Turner (2000), ‘Ganesha’ in Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities, Routledge London, U.K.

- 23 Pranab Bandyopadhyay (1995), Gods and Goddesses in Hindu Mythology, United Writers, Calcutta, India, Pg. 75.

- 24 Orlando O. Espin & James B. Nickoloff (2007), An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies, Liturgical Press, Collegeville, USA, Pg. 539.

- 25 Cybelle Shattuck (1999), Religions of the World: Hinduism, Routledge, London, U.K., Pg. 44-45.

- 26 Charles Phillips, Michael Kerrigan & David Gould (2011), Ancient India's Myths and Beliefs, The Rosen Publishing Group, New York, USA, Pg. 98-101.

- 27 Robert S. Ellwood & Gregory D. Alles (1998), Encyclopedia of World Religions, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 104.

- 28 Constance A. Jones & James D. Ryan (2007), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 223-224.

- 29 David Kinsley (1988), Hindu Goddesses: Vision of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Traditions, University of California Press, California, USA, Pg. 55-64.

- 30 Swami Harshananda (N.D), Hindu Gods and Goddesses, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Madras, India, Pg. 79-80.

- 31 James G. Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, The Rosen Publishing Group, New York, USA, Pg. 385–386.

- 32 Swami Harshananda (N.D), Hindu Gods and Goddesses, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Madras, India, Pg. 82-84.

- 33 Chinese Buddhist Encyclopedia (Online Version): http://www.chinabuddhismencyclopedia.com/en/index.p hp?title=Soma: Retrieved: 19-03-2018

- 34 New World Encyclopedia (Online Version): http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entr y/Soma: Retrieved: 19-03-2018

- 35 James G. Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, The Rosen Publishing Group Inc., New York, USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 659.

- 36 New World Encyclopedia (Online Version): http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Hinduism#The_ four_goals_of_life: Retrieved: 02-03-2018

- 37 Artha (wealth) stands for the means by which this life may be maintained—in the lower sense, food, drink, money, house, land and other property; and in the higher sense the means by which effect may be given to the higher desires, such as that of worship, for which artha may be necessary, aid given to others, and so forth. In short, it is all the necessary means by which all right desires, whether of the lower or higher kinds, may be fulfilled.

- 38 The text known as the Kama Sutra is said to have been composed sometime between the second and fifth century. It attempts to define the relationship between a man and a woman. Kama is the Hindu god of love, the word Kama means ‘pleasure’ a meaning that encompasses any pleasure that can be experienced through the senses.

- 39 In Hinduism, dharma refers to all forms of order. Thus, it can refer to the regular cycles of the sun. But in religious terms dharma refers most specifically to the moral standard by which human actions are judged. The impact of this standard is very broad ranging. At its most universally human, dharma is sometimes said to be the Hindu equivalent of the English word "religion."

- 40 One of the four aims, moksa or mukti is the truly ultimate end, for the other three are ever haunted by the fear of death, the ender. Mukti means “loosening” or liberation. It is advisable to avoid the term “salvation, ” as also other Christian terms, which connote different, though in a loose sense, analogous ideas. According to the Christian doctrine (soteriology), faith in Christ’s Gospel and in His Church effects salvation, which is the forgiveness of sins mediated by Christ’s redeeming activity, saving from judgment, and admitting to the Kingdom of God. On the other hand, mukti means loosening from the bonds of the samsara (phenomenal existence), resulting in a union (of various degrees of completeness) of the embodied spirit (jivatma) or individual life with the Supreme Spirit (paramatma). Liberation can be attained by spiritual knowledge (atmajnana) alone, though it is obvious that such knowledge must be preceded by, and accompanied with, and, indeed, can only be attained in the sense of actual realization, by freedom from sin and right action through adherence to dharma. The idealistic system of Hinduism, which posits the ultimate reality as being in the nature of mind, rightly, in such cases, insists on what, for default of a better term, may be described as the intellectual, as opposed to the ethical, nature. Not that it fails to recognize the importance of the latter, but regards it as subsidiary and powerless of itself to achieve that extinction of the modifications of the energy of consciousness which constitutes the supreme mukti known as Kaivalya. Such extinction cannot be affected by conduct alone, for such conduct, whether good or evil, produces karma, which is the source of the modifications which is man’s final aim to suppress. Mokṣa belongs to the nivṛtti marga, as the trivarga appertain to the pravṛtti-marga.

- 41 Constance A. Jones & James D. Ryan (2007), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 150.

- 42 Hugh B. Urban (2003), Tantra: Sex, Secrecy, Politics, and Power in the Study of Religion, University of California Press, Los Angeles, USA, Pg. 4.

- 43 James G. Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, The Rosen Publishing Group Inc., New York, USA, Vol.2, Pg. 688.

- 44 Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Online Version): http://www.iep.utm.edu/jain/: Retrieved: 16-03-2018

- 45 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): https://www.ancient.eu/article/238/initiation-of-religions-in-india/: Retrieved: 17-03-2018

- 46 Karma literally means “action, ” but it also can be generated by words or even thoughts. It is not produced only by the things one does or says, but also by one’s underlying motives. An individual’s good karma will bring a favorable rebirth in heaven as a god or on earth as a wealthy or high-caste human being. Bad karma will bring an unfavorable rebirth. A person’s current social status reveals how properly he or she lived in the previous life. (James G. Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, The Rosen Publishing Group Inc., New York, USA, Vol.2, Pg. VIII).

- 47 Kevin Trainor (2004), Buddhism: The Illustrated Guide, Oxford University Press, Oxford, U.K., Pg. 61-64.

- 48 Constance A. Jones & James D. Ryan (2007), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 364.