Religious Rituals of Ancient Persia – Yasna & Fire-Temples

Published on: 23-Sep-2024(Cite: Hamdani, Mufti Shah Rafi Uddin & Khan, Dr. (Mufti) Imran. (2020), Religious Rituals of Ancient Persia, Encyclopedia of Muhammad  , Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 635-644.)

, Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 635-644.)

The people of ancient Persia didn’t just meddle with the divinely revealed belief system but rather they also did their best in mutilating the divinely revealed way of life with their so-called ingenuity. Consequently, the Persian way of life became idiosyncratic, and in some aspects, gruesome. The rituals practiced by the ancient Persians show that whenever humanity tried to make the blunder of revolutionizing the divine system, things went out of hand and humanity descended in to the abyss of misguidance.

Religious Buildings

The empire of ancient Persia had no single religion, but rather followers from pagan religions and Zoroastrianism inhabited it. Since followers of different religions had specific religious buildings, Persia was home to the fire temples and other temples. The Persians prayed in the open air or at the top of mountains. Darius used the word ayadana that seems to be a general term for 'temples' in Old Persian deriving from the word yada 'to worship'. Other types of sacred places were known as kusukum or hapidanus; both of which received offering rations. 1

Fire and Fire Temples

Herodotus stated that the Persians had neither a temple nor an altar, more cautiously, he called the similarly shaped structures found on Persian sealing altar shaped or altar 2 and five centuries later Strabo confirmed this fact. Cicero states that Xerxes considered it to be very sacrilegious to keep the gods, whose home was the whole universe, shut up within walls. If so, it was not possible that Artaxerxes II, as is often suggested, was the first one to build fire-temples. Cicero also informs us that the Persians considered it wicked to make sacred statues in human form. No fire-temples were found either at Pasargadae or Persepolis. The Achaemenians only used altars as is evident from Persepolis and seals containing altars.

The later Achaemenians in the 4th century B.C., particularly Artaxerxes II, built temples to the water-goddess Anahita and so it is often presumed that the temple cult started from thereon because the temples were established for the type of fire altars depicted so often on royal Achaemenian seals or architecture which always showed two men wearing typical Persian clothes with wide sleeves and long skirts and a crown and having bows and an arrow case. Since the Magi then wore Median attire only, the figures depicted as facing each other at these altars apparently represent the king and his heir. Yamamoto identified them as the dynastic altars and assumed that it came to symbolize the life of the dynasty and then that of the nation represented by the king. So the dynastic fire was taken as the symbolic center of the nation, and as the representative of the homeland. He added that the size of the altars showed that they could not have been moved; but were fixed in a certain place. Just as the hearth fire was always allowed to expire when the master of the house passed away, the dynastic fire was also allowed to expire whenever the king passed away, which was not surprising since both these practices were governed by the Magian beliefs.

Fire-temples were quite prevalent from the very start of the Sasanian dynasty, which had earlier served as the main caretaker for the temple of Anahita at Istakhar in Pars. But its founder, Ardashir, did not allow the existence of any dynastic fire, but his own, in order to assert his own supreme authority over the entire kingdom he conquered. The king’s chief ecclesiastical advisor, Dastur Tansar, even declared that the king had taken away local (dynastic) fires from the fire-temples and had extinguished them. 3The temples of Zoroastrians were known as Atash-Adarans and Atash-Behrams, where the sacred flame was permanently kept glowing. 4

Both the Arsacid and the Sassanid fire-temples conform to one type: a square building, surmounted by a cupola, within which the sacred fire was kept burning upon an altar in a room that remained completely dark, so that it could not be touched by the light of the sun. 5

Temple of Mithra

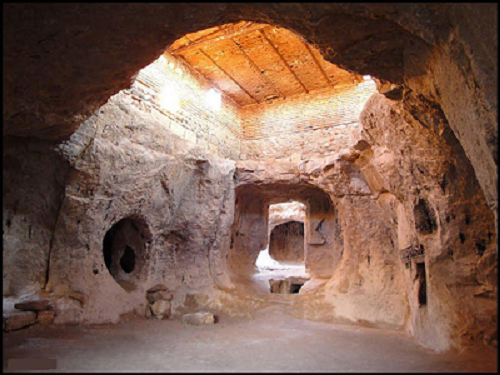

Maragheh was one of Iran's most ancient cities and its suburbs were used to build temples belonging to the religion of Mithraism. One of the temples was located 4 kilometers south of Maragheh in Verjuy (Verjouy) village. Followers of Mithraism built this temple during the Arsacid dynasty (248 B.C.-224 A.D.) by cutting a huge schist stone on the ground and making it an entrance 5.40 meters wide. A steep embankment reached an underground corridor with a crescent-shaped ceiling at the entrance of the cave. The height of the corridor's ceiling was 2.5 meters from the ground and the corridor was 17.60 meters long. The central corridor had a lot of pits that connected to underground rooms with dome-like ceilings. 6

Priests

The priests in Iranian religion were called magi, derived from the word magu ('priest'). Their role in the earlier Median period was described as dream-interpreters and royal advisers. Their importance in the early Achaemenid period was demonstrated by the rebellion of Gaumata the Magus, as reported in the inscription of Darius at Bisitun and the Classical sources. He claimed to be Bardiya (also known as Smerdis, the younger brother of Cambyses), and seized the throne. He was eventually killed by a group of seven nobles including Darius I, as a punishment for his lies and illegal capture of the throne.

Prayer

Worship was offered to the divine beings without the aid of temples or altars or statues and all that was needed for solemnizing the high rituals was a clean, flat piece of ground, which could be marked off by a ritually drawn furrow. The offerings consecrated there, were made not only to the invisible gods, but also to fire and water, which could properly be represented by the nearest domestic fire and household spring, although a ritual fire was always present within the precinct itself, burning in a low brazier. The only continually burning fire was the hearth fire. It was lit when a man set up his home and kept it alight as long as he lived; it was a divinity within the house. It was tended with care and regularly offered with dry wood, incense and fat from the sacrificial animal. 7

The Zoroastrian religious texts explicitly mentioned that Ahura Mazda heard the prayers even in thought. Righteous thinking was also considered a prayer and such prayers lifted the man towards Ahura Mazda. 8 But later on, his followers added further deities and started worshipping them as well. This indeed was a huge blunder since it led millions of Persians astray from the right path.

They held bundles (barsoms) in one hand with the other raised as a sign of prayer. Their noses and mouths were covered with the lower part of their turbans. It was a tradition for the magi to cover their mouths when they stood in front of the holy fire to save it from being polluted by their breath. The barsom was another indication that the priests were participating in a ritual ceremony. Some of the gold votive plaques in the Oxus Treasure that were perhaps presented to a temple also show priests. They wore a Median type of costume, some had a padam 9 with headdress, and they also held barsoms. Sometimes their dresses had bands of decoration and bird designs. 10

Precautions were taken to prevent the state and spread of impurity to the seven creations of Ahura Mazda (vegetation, animals, earth, water, metal, fire, and human beings) by breath and saliva. Naturally, these precautions were and are difficult to observe during everyday activities, but they were and are strictly enforced during religious rituals 11 which are illogical and irrational in truth.

Four Great Prayers

These prayers were embodied in the yasna liturgy and were also constantly recited by Zoroastrians in their private prayers. All were named from their opening words:

Ahuna Vairyo

It was the greatest Zoroastrian prayer, composed by the Zoroastrians but falsely attributed to Zoroaster, himself. Its recitation replaced all other acts of devotion. There are many translations of it, the following deriving essentially from that of S. Insler:

‘As the Master, so is the Judge to be chosen in accord with truth. Establish the power of acts arising from a life lived with good purpose, for Mazda and for the lord whom they made pastor for the poor.’ 12

Airyemaishyo

This prayer, also present in Gathic Avestan, was recited especially at weddings:

‘May longed-for Airyaman come to the support of the men and women of Zarathushtra, to the support of good purpose. The Inner Self which earns the reward to be chosen, for it I ask the longed-for recompense of truth, which Lord Mazda will have in mind.’ 13

Ashemvohu

Most devotions ended with this prayer, which seemed a manthra designed to concentrate the mind on 'asha'. It was once again variously translated. Asha belonged to Asha Vahishta.

Yenhe Hatam

This prayer, was regularly recited at the end of litanies:

‘Those Beings, male and female, whom Lord Mazda knows the best for worship according to truth, we worship them all.’ 14

Kusti Prayers

A Zoroastrian was recommended to pray five times in the 24 hours, at the beginning of each gah, standing in the presence of fire (i.e. actual fire, a lamp, sun or moon). Unless he was already wholly clean, he needed to first make ablution, wash their faces, hands and feet. It was the basic ritual of prayer, then and at all other times, untie and retie the sacred cord, the kusti. This passed three times round the waist, over the sacred shirt, the sudraf, and was knotted back and front. As the wearer untied it and so lost its protection and recited the Kemna Mazda. He re-tied it to the Middle Persian prayer known as 'Ohrmazd Khoday', to be found in all Khorda Avestas, followed by other short Avestan prayers. This sacred cord was worn by men and women both. 15

Fire Worship

The Persians believed that the sacred fire was a gift of Ahura Mazda. 16 Fire-worship was one of the elements of the ancient Aryan religion to which the magi gave new life. There were house-fires, village-fires, and provincial fires. The most sacred of all were the Farrbagh or priest’s fire, the Ghusnasp or warrior’s fire, and the Burzen Mihr or Farmer’s fire. 17

Other Rituals

On the occasion of the completion of the 5th and 7th months of pregnancy, most Zoroastrian households lit a lamp of clarified butter. Upon the birth of a child, a lamp was lit again and kept burning for at least three days in the room where the mother of the child was confined. Some, however, kept the lamp burning for 10 days while others maintained it for 40. One explanation for this custom was that the flame warded off evil influences or forces that may inflict damage or harm. The period of confinement of a woman after giving birth was generally 40 days (which allowed her to be freed from all impurities and defilements), at the end of which she took a purificatory bath in order to mix and socialize with others. During this state of confinement, food was offered to her on a separate plate, and all persons coming in contact with her, even medical attendants, were to undertake special ablutions. The bedding and clothing used by her were also destroyed. 18

The first birthday of a child also marked an important occasion. On that day, the child was taken to the fire-temple where, in a religious ceremony, blessings were invoked and spent ashes from the holy fire were applied to the child's forehead. 19

Zoroastrians bathed ritually for purposes of purity. Their daily life was also divided into 5 different prayer periods. At the age of 7, both, boys and girls had to undergo a ritual known as navjot or new birth to become the members of the Zoroastrian community. On this occasion, they received a white shirt and a sacred thread. They wore them for the rest of their lives. 20

Burial Custom

In the Zoroastrian Sacred texts, Zoroaster was represented as questioning Ahura Mazda about the bodies of the dead – how long it is before a corpse which is laid upon the ground, in light and sunshine, returns to dust; how long before one is buried in the earth; and how long before one is placed in a dakhma. The answer was respectively one year, fifteen years, and not until the dakhma itself crumbled away. Therefore, it was said, it was a great merit to destroy dakhmas, and the man who does so, turns his sins to good. 21

At first, the body was laid in the open under the life-giving sun, which made a path of light to draw the soul upwards to the Cinvat Bridge. 22 In Zoroastrian tradition it is hvaradarasa, or, as it is expressed in Persian, khorsed nigare "beholding by the sun", which was stressed as the chief merit of exposure. The sun's rays, beneficent for the spanta creation, were also powerful to burn away the pollution of the body, which in death belonged to the daevic powers. Moreover, by exposure to birds and beasts, the corrupting flesh was itself swiftly destroyed, sometimes in minutes rather than hours-and there was no sullying of the creations of earth or fire or water. Further, in its harshness, the rite marked a disdain for the nasa 23 which the soul had abandoned; it leveled all men in death, naked alike beneath the sky.

What followed next was known as the dog-sight (sagdid) ceremony. A dog, generally a ‘four-eyed’ dog (a dog with two eye-like spots just above the eyes), was presented so that it gazed at the corpse. Although various reasons were assigned to this ceremony, the purpose in ancient times was to ascertain whether or not life was altogether extinct. This presentation was repeated several times. After the first gaze, however, fire was brought into the room in an urn. Usually a priest sat before the fire, reciting various prayers and tending it continually with sandal wood and frankincense.

About an hour or so before the removal of the body, two (or four if the body was heavy) corpse-bearers, swathed in white vestments except for their faces, entered the house, placed an iron bier by the side of the corpse, recited in a hushed voice the declaration to undertake the ceremony of disposal of the dead (the Dasturi), and then sat silently by the side of the corpse. The recital of this declaration by the corpse-bearers was necessary in order to obtain permission from Ahura Mazda, other divine beings, and past and present important priests to perform the task.

Two priests then stood at a distance from the body and recited the Ahuna Vairya prayer. Half-way through their recitation, they paused for a minute, which signaled the corpse-bearers to remove the body from the slabs of stone and place it over the iron bier. When the priests finished the remainder of their recitation, the sagdid was repeated once again, upon which everyone assembled in the house paid their last respects to the deceased.

The corpse-bearers then secured the body to the bier with straps of cloth and carried it from the house to the ‘Tower of Silence’, or funerary tower (dakhma), which was a massive, round, tower-like building, generally raised on elevated ground or a hill, where dead bodies were exposed to the sun and to flesh-eating birds. A final sagdid followed at the entrance to the tower, after which the body was carried in, stripped of its clothing, and exposed to the sun and the vultures. The bones of the denuded skeleton were left for a while to be dried by the sun and then thrown into a deep well with a deposit of lime and phosphorus. 24

It was believed that whoever came in contact with the dead or committed any act of defilement became unclean and had to undergo a great ceremony of purification known as Bareshnum which lasted for nine nights. Bareshnum, was the Avesta name for the ‘top’ of the head, the first part of the body appointed to be washed in the ceremony after the hands. 25 It was held at the fire temple. A preliminary bath at the fire-temple was followed by various purificatory rituals: a total of eighteen applications of each of nirangdin (consecrated bull's urine), sand, and water; the presentation of a dog thirteen times; and the recitation of various prayers. The candidate, however, observed various specified practices, including meditation and prayer, during the entire period. 26

Sacrifices

The ancient Persians mistakenly believed that gods required to be propitiated so that they might extend their favors to men. When men began to lead settled agricultural life, they began to offer the first fruits of the harvest and produce of the cattle as thanks giving offerings to them. With growing prosperity, they prepared rich repasts of sumptuous food and wine and invoked them to alight on the hallowed place where ceremonial rites were performed, or kindled fire to dispatch the sacrifices to heaven on its flaming tongues. The Persian sacrificial offering consisted of milk and melted butter, grain and vegetables, flesh of goats and sheep, bulls and horses, and the exhilarating Soma-Haoma beverage. Elaborate rituals were performed to obtain coveted boons, to gain the remission of sins, and to stave off the terrors of hell. The consecrated food was consumed by the sacrificers to reap the merit. The altars were reeking with the blood of animals that were sacrificed to innumerable gods. Zarathustra did away with such sacrifices and purified the rituals.

The later Avestan texts speak of distinct functionaries who officiated at the sacrificial ceremonies. The head of this group was zaotar which basically referred to ‘the sacrificer’. As a zaotar, the person seeks the vision of Ahura Mazda and longs to hold communion with him. He was the priest of the highest rank who stood above the seven other priestly titles existing in the religion of Zarathustra. The food offered as a ceremonial offering was known in the Avestan texts as myazda, and the texts states that the faithful would offer myazda with homage unto Ahura Mazda and Asha. The draonah or the sacred cake formed an indispensable article of offering in the later period. 27

Festivals

Younger Avestan texts allude to 6 seasonal festivals that seem to correlate with an ancient pastoral–agricultural calendar. The Avestan phrase yairiia asahe ratauuo, meaning ‘the seasonal right times’ describes both the festivals and their seasons. The liturgical text Afrınagan ı Gahanbar lists these festivals in order, beginning with that of mid‐spring, Maidiioizarəmaiia. The other 5 festivals were: Maidiioisəma (mid‐summer); Paitishahiia (fall harvest); Aiiāθrima (the ‘homecoming’ of the herds); Maidiiairiia (‘mid–year’ or ‘mid‐season’, that is, winter). The last festival of the year, before the spring, was Hamaspaθ‐maedaiia, a name of uncertain meaning. The earliest source for the festival of Hamaspaθmaedaiia refers to it as lasting up to ten days. It was dedicated to the collective souls of the faithful who were living, dead, or have yet to be born. Welcoming the frauuasis with reverence and offerings at this time, and blessing the souls of the living and dead together, was thought to bring benefit to the world. 28

At some point, each of the 6 seasonal festivals became linked with one of the creations associated with the ameṣa speṇtas: Maidiioizarəmaiia was connected with the sky, and the subsequent 5 festivals were correlated with the waters, earth, plants, animals, and humans respectively. Fire, the 7th element of creation in the Zoroastrian cosmology, was liturgically incorporated into the festival of Nowrūz, which means ‘New Day’, implying the first day of the New Year. This last festival is thought to have a very ancient origin, although it is not referred to in Avestan texts. As the religion developed, Nowrūz became the most significant Zoroastrian festival, celebrating the creative activity of Ahura Mazda.

Mehragan (Old Persian Mithrakana) was one of the most important Iranian celebrations, mirroring the New Year festival, Nauruz, which was held at the spring equinox. Originally the Iranian people, like the Indo-Aryans considered the New Year to begin in the fall; thus, the annual festival of Mithra was likely the most important occasion of the year. In Achaemenid times, both Mithrakana and Nauruz were major official occasions presided over by the state. The Achaemenid Mehragan ceremony culminated in the ritual killing of a bull. Iranian Zoroastrians celebrated Mehragan by conducting an animal sacrifice, usually a sheep or a goat. Significantly, Mehragan was the only Zoroastrian festival in which (some) priests omitted a formal dedication to Ahura Mazda, dedicating the ceremony instead to Mithra. 29 Other Festivals are mentioned in the First Volume of Seerat Encyclopedia under Zoroastrianism.

In order to discuss the majority of religious rituals practiced by the ancient Persians which seemed to be very purifying and logical were nothing more than an insult to humanity and its traditions. The Persians believed that by following these religious traditions, they were pleasing God but in reality, they were misleading themselves. Some of the priests knew the reality but still kept following this path because it helped them in achieving their mundane goals. Moreover, it was one of the key reasons for the fragility of the ancient Persian society as well.

- 1 John Curtis & Nigel Tallis (2005), Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia, The British Museum Press, London, U.K., Pg. 151-152.

- 2 Bernard Goldman (1965), Journal of Near Eastern Studies: Persian Fire Temples or Tombs, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA, Vol. 24, No. 4, Pg. 305.

- 3 Dr. Kersey H. Antia, Fire and Fire Temples in Zoroastrianism through the Ages, Pg. 1-6. http://www.avesta.org/antia/Fire_and_Fire-temples_in_Zoroastrianism_Through_the_Ages: Retrieved: 04-03-2019

- 4 Faredun K. Dadachanji (1941), Philosophy of Zoroastrianism and Comparative Study of Religions, The Times of Indian Press, Bombday, India, Vol. 1, Pg. 38.

- 5 S. A. Cook, F. E. Adcock, M. P. Charlesworth & N. H. Baynes (1934), The Cambridge Ancient History: The Imperial Crisis and Recovery, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., Vol. 12, Pg. 120.

- 6 Quoted by Afshin Tavakoli in the Daily Iran Newspaper, Dated: May 16, 2004, The Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies: https://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/Archaeology/Ashkanian/verjuy_mithra_ temple.htm: Retrieved: 04-03-2019

- 7 Mary Boyce (1975), Journal of the American Oriental Society: On the Zoroastrian Temple Cult of Fire, American Oriental Society, Michigan, USA, Vol. 95, No. 3, Pg. 455.

- 8 Maneckjee Nusservanji Dhalla (1938), History of Zoroastrianism, Oxford University Press, New York, USA, Pg. 70.

- 9 A piece of white cloth which the priest used to cover his mouth in order to protect the fire from being polluted by his breath. (Albert De Jong (1997), Traditions of the Magi: Zoroastrianism in Greek and Latin Literature, Brill, Leiden, Netherlands, Pg. 150.)

- 10 John Curtis & Nigel Tallis (2005), Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia, The British Museum Press, London, U.K., Pg. 152.

- 11 S. A. Nigosian (1993), The Zoroastrian Faith: Tradition & Modern Research, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, Canada, Pg. 108.

- 12 Mary Boyce (1990), Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA, Pg. 56-57.

- 13 Ibid.

- 14 Ibid.

- 15 Mary Boyce (1990), Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA, Pg. 58.

- 16 George Foot Moore (1912), The Harvard Theological Review: Zoroastrianism, Harvard Divinity School, Massachusetts, USA, Vol. 5, Pg. 190.

- 17 S. A. Cook, F. E. Adcock, M. P. Charlesworth & N. H. Baynes (1934), The Cambridge Ancient History: The Imperial Crisis and Recovery, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., Vol. 12, Pg. 119.

- 18 S. A. Nigosian (1993), The Zoroastrian Faith: Tradition & Modern Research, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, Canada, Pg. 98.

- 19 Ibid, Pg. 99.

- 20 Robert S. Ellwood and Gregory D. Alles (2007), The Encyclopedia of World Religions, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 490.

- 21 Mary Boyce (1996), A History of Zoroastrianism: The Early Period, Brill, Leiden, Netherlands, Vol. 1, Pg. 326-327.

- 22 Cinvat Bridge or Cinwad Puhl was traditionally thought to mean ‘the bridge of the separator’ but recently shown to be the bridge of the accumulator/collector, the name of a bridge that, according to a Mazdayasnian/Zoroastrian eschatological myth, leads from this world to the next and must be crossed by the souls of the departed. The bridge lies on the peak of the cosmic mountain Harburz (Alborz), called Cagad i Daiti, with one end in the south leading up to paradise; the other lies in the north, and below it, beneath the earth, lies hell. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/cinwad-puhl-av Retrieved: 03-03-2019)

- 23 The Corpse or the dead body which the soul had abandoned. (Mary Boyce (1990), Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA, Pg. 65.)

- 24 S. A. Nigosian (1993), The Zoroastrian Faith: Tradition & Modern Research, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, Canada, Pg. 102-103.

- 25 F. Max Muller (1990), Sacred Texts of the East: Pahlavi Texts (Translated by E. W. West), Atlantic Publishers & Distributers, New Delhi, India, Pg. 431.

- 26 S. A. Nigosian (1993), The Zoroastrian Faith: Tradition & Modern Research, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, Canada, Pg. 105.

- 27 Maneckjee Nusservanji Dhalla (1938), History of Zoroastrianism, Oxford University Press, New York, USA, Pg. 73-74.

- 28 Michael Stausberg, Yuhan Sohrab – Dinshaw Vevaina & Anna Tessmann (2015), The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, U.K., Pg. 380-381.

- 29 Richard Foltz (2013), Religions of Iran: From Prehistory to Present, Oneworld Publications, London, U.K., Pg. 29-30.