Religious Beliefs of Ancient Persia – Zoroastrianism

Published on: 21-Sep-2024(Cite: Khan, Dr. (Mufti) Imran & Hamdani, Mufti Shah Rafi Uddin. (2020), Religious Beliefs of Ancient Persia, Encyclopedia of Muhammad  , Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 622-634.)

, Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 622-634.)

Like most of the civilizations of the ancient world, the religion of ancient Persia was also confusing. The people were polytheists and naturalists who worshipped the natural phenomenon and other forged deities. In that polytheistic age, Zoroaster appeared on the scene and tried to connect the people to their One and Only Supreme God but his efforts did not yield much results in the beginning. Zoroaster invited the people to shun their self-made beliefs and accept the existence of Ahura Mazda which meant ‘The Omniscient’, and ‘The Creator of the Universe’. While Zoroaster was alive, he only preached the monotheistic existence of God, however, after he passed away, his followers did not heed him. They associated 6 other mortal beings to Ahura Mazda and started worshipping them as well.

The ancient religion of the Persians was preached by Zoroaster, who taught them about one God, and that he alone was to be worshipped and served, but as time went on this religion was corrupted, and the Persians recognized two great beings – Ahuramazda, or Hormuzd (the lord of all that was good) and Ahriman (the lord of all that was bad) and thus became dualists, or the worshippers of the two principles. 1

Zoroastrianism was the religion named after Zarathustra, who may have lived sometime around the beginning of the first millennium B.C., but his date of existence is not certain. At that time the Iranians believed in a variety of gods, however, Zoroaster reformed their ancient religion and promoted the belief that there was one great god, Ahuramazda, his followers corrupted the religion by claiming that this god was supported by divine beings or immortal spirits known as yazatas. 2

Apart from Zoroastrianism, in the Achaemenid period the Iranian religions known as Mithraism, Zurvanism and Mazda-worship are also attested. Mithraism was based on the sun god Mithra. His cult later spread by Roman soldiers through Europe as far as England, and its traditions influenced Christianity. Zurvanism was named after Zurvan, the god of limitless time, who was thought to have given birth to Ahuramazda and to Ahriman, the personification of evil. Mazda-worship referred to the veneration of Ahuramazda, but not in association with the teachings of Zoroaster. At the same time local religions that existed in Iran before the arrival of the Achaemenid Persians continued to flourish. After their arrival from the north and their settlement near the Elamites, the Persians could have adopted Elamite religious beliefs, but their religion remained Iranian and in due course influenced the Elamites. At the same time, Elamite religion may have had some influence on Persian religion, but the Elamites did not influence Persian religion as much as it was inspired by Iranian elements. 3

In the immense empire which Cyrus had founded and Darius-I had re-established in its unity, every subject people kept its own religion. The Great Kings were eclectics, who did not proselytize; on the contrary, they were initiated in to the worship of foreign deities and the kings also took them as their protectors.

The Medo-Persian group had three religions – that of the king, that of the people and that of the Magi. The first of these religions’ places Ahura-Mazda, the greatest of all the gods who created heaven and earth at the head of the universe. The king reigned by the grace of Ahura-Mazda and it was this being which gave the king power and it was his support which enabled the king to conquer his rebels as proclaimed by Darius in the Behistun inscription. 4

Concept of God

The ancient Persians were polytheistic. There were probably many local deities, war gods, gods of agriculture, and of storms and many more. Animistic ideas had their place also. As for the natural elements, and especially in fire, were their forces to be personified, adored, placated, or worshipped. As in the case of other civilizations, these things increased in number as time passed till the people became entangled in a mass of superstition, and surrounded by the clouds of divinities of good purport and hope and demons of evil. 5

The names of Mithra and Anahita were first mentioned in the inscriptions of Artaxerxes Mnemon and Ochus. The former who was originally the god of compact and later became the god of a secret religion which had devotees all over the Roman Empire. The Kings religion had changed in character; the notion of Ahura-Mazda alone in the sky had grown old, hence new deities sprung up by his side, younger and therefore more active.

Mithra was worshipped by the Iranians in very early times, although he was not introduced in to the special religion of the kings until the end of the 5th century. In the pre-Avestic religion he was shown as a mediator between the upper world of light and the lower world of darkness. From Artaxerxes II onwards, the kings honored him as the bestower of the royal glory, called him to witness their oaths and invoked him in battle.

The introduction of Anahita in to the Iranian pantheon showed that the royal religion was becoming impregnated with Chaldean astrology. It was in this form that it survived in certain kingdoms of Asia Minor after the fall of the Persian Empire. The people worshipped the four elements – light (divided in to the light of the day, or the sun, and that of the night or the moon), water, earth, and wind. 6 The description of the other forged gods is given below:

Marduk

Marduk, also known as Bel 7 was a highly revered god of Babylon. 8 He presided over justice, compassion, healing, regeneration, magic, and fairness, although he was also sometimes referenced as a storm god and agricultural deity. 9 After the conquest of Babylon, the cult of Mithraism came into contact with Chaldean astrology and with the national worship of Marduk. For a time, the two priesthoods of Mithra and Marduk (magi and chaldaei respectively) coexisted in the capital and Mithraism borrowed much from this intercourse. This modified Mithraism travelled farther northwestward and became the State cult of Armenia. 10

Anahiti

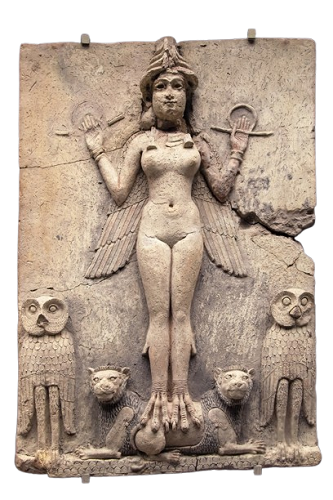

Anahiti, also called Anahita was an ancient Iranian goddess of royalty, war, and fertility; she was particularly associated with the last. Possibly of Mesopotamian origin, her cult was made prominent by Artaxerxes II, and statues and temples were set up in her honor throughout the Persian Empire. A common cult of the various peoples of the empire at that time, it persisted in Asia Minor long afterward. In the Avesta, she was called Ardvi Sura Anahita (Damp, Strong, and Untainted); this seems to be an amalgam of two originally separate deities. In Greece, Anahiti was identified with Athena and Artemis. 11 Anaitis was the Greek rendering of what appears to have been the name of the goddess of the planet Venus, who seems to have been worshipped by the Medes and Persians before they adopted Zoroastrianism. 12

Healing gods

Airyaman: Airyaman was represented in the Avesta as the healer par excellence. He was a kind, beneficent deity, essentially helpful to man, both in India and in Iran. The name itself meant 'the friend, the companion.' 13 The heavenly nature Airyaman does not show up in the Gathas, the most seasoned writings of Zoroastrianism and considered to have been made by Zoroaster himself. In the few cases where the term appears (Yasna 32.1, 33.3, 33.4, 49.7), Airyaman is a typical thing meaning the social division of clerics. 14

Thrita: The other great physician-god of Iran was Thrita. Thrita, like Trita, was an old, wise, and very beneficent deity, a deliverer, a repeller of all the foes that threatened man's existence. He was a bestower of long life. Though he was not explicitly represented as a curer of diseases, his connection with the plant of life, the soma, made him a powerful healer. 15

As Thrita, he was the healer and preparer of haoma and the one who drove away serious illness and death from mortals. Thrita was the third man who prepared haoma for the corporeal world as his name meant third. His prayers to Ahura Mazda brought all the healing plants that grow round the Gaokerena tree in Vourukasha, the cosmic ocean. As Thraetaona (Faridun in the later texts), he was a healer and a victorious warrior. According to their beliefs, he battled the three-headed, three-jawed, six-eyed mighty dragon, Azhi Dahaka. He was called upon to relieve itches, fevers, incontinency, and to keep evil people away. These discomforts were all attributed to the power of Azhi-Dahak. Thrita defeated the dragon with his club but could not slay him.

When he finally took a sword and stabbed the evil dragon, a multitude of horrible creatures crept from his loathsome body. Fearful of the world being filled with such vile creatures as snakes, toads, scorpions, lizards, tortoises, and frogs, Thrita refrained from cutting the monster to pieces. Instead, he bound and imprisoned him in Mount Demavand, where to this day, he causes earthquakes. It is said that mortals would one day regret Thrita's action. It is Thraetaona who seized Yima's ‘khvarenanh’ (his glory) when it left his body and then became the ruler of Yima's realm. He divided the kingdom between his sons Airya, Cairima, and Tura. In other legends, Thrita was represented as the father of Thraetaona. Thrita was killed by Azhi Dahaka (who represents frost). Thraetaona avenged his father's death by tying Azhi Dahaka to Mount Demavend. He sometimes revealed himself in the shape of a vulture. 16

Mithra

Mithra (Mitra) was one of the principal deities of the early Indo-Iranian pantheon. Originally the god of contracts —his name meant ‘that which causes to bind’—his enforcement of verbal commitments was central in a pastoral–nomadic society that lacked any formal policing agency. Spoken agreements were the very foundation of social stability; failure to uphold them could lead to anarchy. Mithra was (and to some extent, remains) an object of veneration in Zoroastrianism and Hinduism, with both Avestan and Vedic rituals devoted to him. 17

He was one of the most important Yazata in the Avesta Book. This name has been mentioned in the Avesta and ancient Persian as Mithra (Miθra), in Sanskrit as Mitra, in the Pahlavi text as Mitr or Miθra and in the Modern Persian as Mehr. The meaning of this word was the friendship, contract and love. He was the god of light and brightness. One of the longest Yashts of Avesta, namely; Mihr (Mehr) Yasht is by his name. The name of Mithra has also been mentioned in the Achamenian king’s inscriptions beside the name of Ahura Mazda and Anāhita (goddess of Water). 18

Rashnu

Along with Mithra and Sraosha, Rashnu passes judgment of the souls of the dead on Chinvat Bridge. He held the golden scales. 19 The name was derived from a verbal base raz which meant ‘to direct, make straight and judge’. 20 He was the Yazata which is the Avestan language word for a Zoroastrian concept with a wide range of meanings but generally signifying a divinity. According to some historian, he was merely an angel but for Prods Oktor Skjaervo he was the god of straight and correct behavior and, in the beyond, the judge who weighed the deeds of the dead on a balance. 21

Overall, the concept of God in the mind of the Persians was not clear since it lacked rationality, practicality and most importantly religiosity. Whether this concept was analyzed empirically, rationally, or even intuitionally, the result was that it was faulty since it was created by the limited minds of the humans.

Other Religions

The empire of ancient Persia was not limited to the boundary of a single country but was rather spread over a vast territory which encompassed many countries. Therefore, there was no single national religion of the empire. Most territories followed a similar religion but others followed the religion prevalent in their area.

Zurvanism

The earliest mentions of Zurvan appear in tablets dated to about the 13th and 12th centuries B.C., found at the site of the ancient Mesopotamian city of Nuzi. Known also as the god of growth, maturity, and decay, Zurvan appeared under two aspects: Limitless Time and Time of Long Dominion. Zurvan was originally associated with three other deities: Vayu (wind), Thvarshtar (space), and Atar (fire).

Zurvan was the chief Persian deity before the advent of Zoroastrianism and was associated with the axis mundi, or the center of the world. The most common image of Zurvan depicts a winged, lion-headed deity encircled by a serpent, representing the motion of the Sun.

As a modified form of Zoroastrianism, Zurvanism reappeared in Persia during the Sassanian period (3rd–7th century A.D.). Zurvanite theories equated the two Zoroastrian deities Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu or Ahriman, a belief strongly disputed by orthodox Zoroastrians. Zurvanite thinking influenced Mithraism, as well as Manichaeism and other schools of gnostic belief. Zurvanism died out a few hundred years after the advent of Islam in Iran in the 7thcentury. 22

Mancheism

Manichaeism, the first and most important of the two schismatic movements in Zoroastrianism (the other, Mazdakism, will be discussed later), arose early in the 3rd Christian century within the Persian Empire. It was there combated and execrated as violently by orthodox Zoroastrianism as it was by orthodox Christianity when it spread westward into the imperial domains of Rome. Mani endeavored, by making a synthesis of elements from various existing religions, to form a new religion, eclectic in character and inspired by the fervor of his own idealistic enthusiasm, one that should not be confined by national borders but be universally adopted. In other words, Mani's aspiration was to bring the world, Orient and Occident, into closer union through a combined faith, based upon the creeds known in his day. 23

Mani himself indicated the date and place of his birth. In the Shabuhragan (composed in Middle Persian in honor of Shahpur I, whence its title), in the chapter titled ‘On the Coming of the Prophet’; Mani says that he was born in Babylonia in 215 or 216 A.D. Only the name of the head of the family, Mani's father, is known with certainty. The Manichaean compilation ‘On the Origin of His Body’, written in Greek in a small parchment manuscript volume, used to refer to it-calls Mani's father Pattikios, a Hellenized form of the Iranian Pattig or Patteg. 24

He was accorded a spiritual vision in his early youth and at about 20 years of age, inspired by divine revelation, he came forward as a false prophet; the date of his first appearance in public was on the coronation day of the Sassanian King Shahpur (Sapor) I, which is usually reckoned to have been March 20, 242 A.D. Although his preaching seems to have met with favor for a time in Persia, the glowing opposition of the Zoroastrian priests to this 'fiend incarnate' (or better translated, crippled devil,' since he appears to have been lame) led Shahpur some years later, to banish Mani from the Persian realm. During the long period of exile that followed (more than 20 years) he is said to have preached his doctrines in the region of Northern India, Tibet, Chinese Turkistan and Khurasan, undoubtedly absorbing ideas himself wherever he went.

He ventured at last to return to Persia, meeting with royal consideration during the brief reign of Ormazd (Hurmizd) I (272-273 A.D.); but shortly afterward, owing to priestly intrigues at the court, Mani was put to death by the latter monarch's successor Bahram I, early in the year (273 or) 274 A.D. The manner of his death was horrible. He was flayed alive, and the body then decapitated, while his skin was stuffed with straw and hung up at the royal gate as a warning to future heretics. Cruel persecution of his adherents immediately followed his martyrdom, but this did not hinder the rapid spread of Mani's faith. Though banned from Persia, Manichaeism was soon disseminated westward to the extreme confines of the Roman Empire and eastward through Central Asia, reaching ultimately as far as China where, though it was always sporadic, there are definite traces of it as late as the 17th century.

The religion of Mani, as noted above, was distinctly and designedly a synthesis. Among his spiritual predecessors, he especially acknowledged Zoroaster, Buddha, and Jesus as pioneer revealers of the truth which he came to fulfil. He accounted Zoroaster's dualistic doctrine of the fundamental struggle between light and darkness, soul and matter, to be at basis the solution of the problem of good and evil. He found in the teachings of the gentle Buddha certain lessons for the conduct of life to be accepted everywhere by mankind. He recognized in Jesus

as pioneer revealers of the truth which he came to fulfil. He accounted Zoroaster's dualistic doctrine of the fundamental struggle between light and darkness, soul and matter, to be at basis the solution of the problem of good and evil. He found in the teachings of the gentle Buddha certain lessons for the conduct of life to be accepted everywhere by mankind. He recognized in Jesus  a verified ideal and claimed to be the Paraclete promised by Christ and for whom the world was seeking. This eclectic character of Mani's religion, and the coloring by the faiths with which he came in contact, made the new creed easier of adoption, and his followers were later able, if necessary, to pass themselves off as a sect of one or other of the religious communities among which they spread their Master's teachings. In the West, for example, the Christian elements tended to be more strongly emphasized, in the East certain Buddhistic elements came perhaps more to the front, but at the basis of Mani's conception of the universe lay the old-time Persian doctrine of dualism, taught centuries earlier by Zoroaster, but amplified, modified, and above all, spiritualized by Mani.

a verified ideal and claimed to be the Paraclete promised by Christ and for whom the world was seeking. This eclectic character of Mani's religion, and the coloring by the faiths with which he came in contact, made the new creed easier of adoption, and his followers were later able, if necessary, to pass themselves off as a sect of one or other of the religious communities among which they spread their Master's teachings. In the West, for example, the Christian elements tended to be more strongly emphasized, in the East certain Buddhistic elements came perhaps more to the front, but at the basis of Mani's conception of the universe lay the old-time Persian doctrine of dualism, taught centuries earlier by Zoroaster, but amplified, modified, and above all, spiritualized by Mani.

He postulated the existence of Two Principles from the beginning to eternity. To Mani, Light was synonymous with spirit and good, Darkness with matter and evil. This was a fundamental tenet of the faith. 25

Mazdakizm

As attested in Arabic, Middle Persian, and Byzantine sources, Mazdakism was a socio-religious movement in the late 5th and 6th centuries which in some way deviated from the official or mainstream forms of Zoroastrianism, that the Sasanian authorities endorsed. A former Zoroastrian priest named Mazdak produced a cosmography based on the dichotomy between light and dark, in some ways similar to Manichaean cosmology. Challenging the structures of Sasanian society, Mazdakism sought to redistribute land and other property among members of the society regardless of their social rank. Mazdak also promoted a form of sexual communalism. In literature, Kavad’s downfall is attributed to his affiliation with Mazdakism, the preaching of which brought havoc to the Sasanians’ rule of state. 26

Like both Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism, Mazdakism had a dualistic cosmology and worldview. However, his sect was believed to be more humane in comparison with Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism. Unlike Mani, Mazdak wanted to exploit his religious preach to reform his society and, in his view, people could not eradicate unjust cast without a clear plan to fight against corruption and oppressors. Both shared a mutual view on dualism in which two original principles of the universe are Light, the good one and Darkness, the evil one. Light was characterized by knowledge and feeling, whereas Darkness was ignorant and blind, and acts at random. Therefore, to weaken the Darkness, the world needed to be cleansed from symbols of ignorance, oppression and corruption by a revolution against forces of evil and to establish a social order on the base of justice instead. His difference with Mani was on the view on Darkness and Light: Light acted by design and free will, whereas Darkness acted at random. As a result, mixture of Light and Darkness, unlike Mani's view, happened randomly and was not planned. Mazdak believed in three distinguished elements (Fire, Water, Earth), unlike Mani who believed in five (Ether, Wind, Light, Water and Fire). Mazdak believed that semi-eternal evil power (Satan) was formed by evil elements as good power (God), who in Manichaeism was being called king of Light, and was a production of three blessed elements. Such sect was based on communism in which all people were equal and they should be able to access to wealth and women equally. 27

The essential tenets of Mazdakism, as reported by the Greek and Arabian historians, seems to have been as follows: All men, by God's providence, were born free and equal, none brought into this world any property or any natural right to possess more than another. Property was, therefore, theft. Property and marriage were human inventions, contrary to the will of God, who required the equal division of all good things, among all the people, and forbids the appropriation of particular women by individual men. Adultery, incest and theft were really not crimes; but the necessary steps for the re-establishment of the laws of nature, in a corrupt society. Mazdak also preached the sacredness of animal life, the absention from animal food other than milk, cheese and eggs; simplicity in dress, moderation of all appetites and devotion to the primordial cause of all things. 28

Zoroaster

Zarathustra, known as Zoroaster by the Greeks, 29 was an important religious figure in ancient Persia, whose teachings became the foundation of a religious movement named Zoroastrianism, a tradition that largely dominated Persia until the mid-7 th century. 30

According to the tradition in the Parsee books, Zoroaster was born in 660 B.C. and died in 583 B.C.; but many scholars claim that he must have flourished at a much earlier time. 31 Some claim that his date of birth could be anywhere between 600-6000 B.C. 32 Eventually, many myths developed around his life, placing him clearly among those heroes associated with the heroic monomyth. It was said that his mother, Dughda, dreamt that good and evil spirits were fighting for the baby in her womb. At birth, the baby laughed. Wise men warned the wicked king Duransarun, that the child was a threat to his realm, and the king set off to kill the baby Zoroaster. Miraculously, the would-be murderer’s hand was paralyzed. When demons stole the child, they also failed to kill him; his mother found him peacefully sleeping in the wilderness. Later, the king sent a herd of oxen to trample his enemy, but the cattle took care not to hurt Zoroaster. The same thing happened when horses were sent to trample him. Even when the king had two wolf cubs killed and had the baby Zoroaster put in their place in the den, the mother wolf’s anger was quieted, and sacred cows were sent to suckle the child. In adulthood, Zoroaster was resented by followers of the old tradition, but he convinced many with his miraculous cures, and even though he was killed at an advanced age by soldiers while he was carrying out a ritual sacrifice, it is said that Zoroaster will one day return as a final prophet or saoshyant. 33

His religious poems, known as Gathas, provide the major evidence for his teachings. In contrast to the then dominant polytheism, Zarathustra attributed the creation of the world to a single being, Ahura Mazda, the “wise lord.” His followers added that the single being was attended by seven lesser spirits, the Amesha Spentas. These, in turn, are opposed by evil spirits known as daevas. The world in which human beings live is the site of the struggle between these two forces, but Zarathustra taught that in the end, good would triumph and the current world would be destroyed by fire 34 which was a figment of their imagination.

Zoroastrian Doctrine

According to Zoroastrian doctrine, before all existence there were two spirits, one good, creative of life, and beneficent; the other one evil, inimical to life, and malevolent. The two spirits were eternally opposed to one another. Ahura Mazda was identified in the tradition with the spirit of goodness, called Spenta Mainyu, translated as ‘Holy or Beneficent Spirit’. He created the spiritual world first, then the physical realm as a means of combating and finally annihilating Angra Mainyu, the ‘Hostile Spirit’. The physical world was originally perfect when created, but was invaded and was then afflicted by the Hostile Spirit. Zoroastrianism urges those who listen to choose goodness and smite evil by aligning themselves with Ahura Mazda and his spiritual helpers, the amesha spentas, ‘blessed immortals’ and yazatas ‘ was the saoshyant who has already arrived to this world and became victorious over the forces of evil. The religion was thus based on a vision which was primarily soteriological and eschatological, promising deliverance from imperfection, through human effort aligned with the divine will.

was the saoshyant who has already arrived to this world and became victorious over the forces of evil. The religion was thus based on a vision which was primarily soteriological and eschatological, promising deliverance from imperfection, through human effort aligned with the divine will.

Concept of god

Since the Godhead was not visible, it was worshipped in the form of a symbol of fire. Zoroastrians venerated all other natural elements and are adjoined to promote their growth and sanctity. Yasna 17.11 described five types of fire or energy, which the Pahlavi commentary described as beneficent, diffusing goodness, providing the greatest bliss, the greatest swiftness (lightning), and the most holiness. It described the first one as burning in the Atash Bahram, and the last one as burning in the highest heaven before Hormazd. However, the Bundahishn mentions the above-mentioned first fire as the fire burning before Hormazd, and the last one as the one burning in the Atash Bahram, which may indicate some differences in the belief or practices over the years. 36

Belief about Non-Humans

Classical Zoroastrianism (i.e., from the Sasanian period, 224-751 A.D.), divided nonhuman animals into ‘good’ and ‘evil’ species. Good species needed to be protected at all costs by humans, who were subject to extremely harsh penalties if they abused them. On the other hand, it was the sacred duty of believers to kill ‘evil’ species (collectively called khrafstar) at every opportunity, since by doing so they reduced the foot soldiers available to Ahriman in his campaign for advancing evil in the world.

The Zoroastrian creation myth in the Bundahisn has the bull as the primordial animal, from which all other beneficent species were descended. In other late Zoroastrian texts, however, the dog appeared more prominently than the cow, ranking next to humans in the ‘good’ creation. Indeed, according to later tradition, if only one human was present for a religious ritual requiring two persons, a dog could be substituted for the second person.

As for the evil species, the systematic killing of undesirable animal species by Persians was first recorded by Herodotus in the 5th century B.C. A millennium or more later, Middle Persian texts such as the Shayest ne-shayest describe the practice as a sacred obligation. The Bundahisn states that every Zoroastrian needed to possess an implement for killing snakes. Larger insects, such as big-bodied beetles, tarantulas, or the huge local wasps, were regarded as unclean in themselves, and it was a virtue to kill them, using Ahriman’s own weapon of death to reduce his legions. 37

Concept of Burial and Afterlife

Zoroastrians did not bury, cremate or submerge their corpses in water, in order to prevent dead matter from coming into direct contact with, and thus polluting, the elements of earth, fire and water; the creations of their one supreme god Ahura Mazda. According to their religion, any dead matter was polluting. Pollution and death were considered to form no part of Ahura Mazda’s creation but were inflicted on it by evil. The latter was a force entirely unconnected with and extraneous to God. Evil invaded Ahura Mazda's perfect cosmos from the outside of it, and brought pollution, destruction and death. The purpose of creation, human beings in particular, was to reduce the presence of pollution as much as possible and thus contribute towards the eventual complete defeat and removal of evil from the world, a task expected to be completed at the end of time with the help of a Savior. At that point evil will be defeated in a final battle and forced to withdraw powerless from the world to its place of darkness, where it came from originally.

When a person died, the greatest care was taken to contain the pollution issuing from the corpse, which needed to be disposed of within a day, if possible, on the same day by feeding it to the birds and beasts. The guiding principle of all Zoroastrian funerary observances was the segregation of the dead body in order to prevent contamination, infection and harm to the living world. Funeral ceremonies were designed to prevent any direct contact of the living with the dead body, and to dispose of this source of pollution as quickly as possible.

While the dead body was swiftly disposed of, rites for the immortal soul were complex and prolonged. During the critical three days after death, family members and friends kept a fire, or a flame (divo), burning in the house on the spot where the deceased had been lying, and fed it with sandalwood and incense. This practice was also followed in the buildings (bungli) at the Towers if the three-day rites are performed there. While abstaining from eating meat, the mourners supported the soul of the deceased by saying prayers. All the obligatory prayers were uttered twice, the repetition being on behalf of the departed person.

For the Zoroastrians, death was a temporary state. They believed that death would be reversed at the end of time when evil would be defeated and forced to withdraw to the place where it came from in order to destroy Ahura Mazda's perfect world. As a result, the dead were expected to rise. All resurrected bodies would then undergo the universal judgment. This would take the form of a stream of molten metal through which the dead needed to pass. The stream would feel as pleasant as a bath of warm milk to the truthful worshippers of Ahura Mazda, but as painful as molten metal to the deceitful worshippers of the false gods, the daevas. Eventually all resurrected bodies would emerge purified from the molten metal and each of them would be united with his or her soul. The resurrected would display individual features, so that husband and wife, father and son, and mother and daughter would recognize each other. Their bodies would be forever in the perfect youth of the fifteen-year-old, and they will enjoy all the physical pleasures of life but without procreation and without any adverse consequences. 38

The Routledge Encyclopedia states that a human soul recorded a person’s acts of virtue and wickedness which would be respectively rewarded and atoned for in a spiritual state after one life in the physical state. Time would end, there would be a resurrection of all the dead and a last judgment of all souls. A new, spiritually and physically perfect world would be made here on earth, and evil would be banished for eternity from the universe. There would be a return to the pristine perfection of the original creation, but with the fullness of physical and spiritual multiplicity of forms un-afflicted by evil in a state called Frashokereti (‘Renovation’). 39

When it came to religion, the illiteracy of the ancient Persians was evident. To ignore divine guidance and to accept illogical forged beliefs required a high level of ignorance, which was displayed by the ancient Persians by adopting falsehood. Humans need to believe in divine guidance because the capacity of the human brain is limited and even if the intellect of all the humans was combined (excluding the prophets) none would have been able to create a religious system which would have led them to the right path. Those who have understood this human weakness and have adopted the divine revelation have succeeded in this world and will also succeed in the hereafter, but those who have tried to stand tall in front of the divine revelations like the Persians and many before and after them, have failed in both worlds.

- 1 H. F. Haig (1923), Persia, A. & C. Black Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 22.

- 2 Additions by Zoroaster’s followers.

- 3 John Curtis & Nigel Tallis (2006), Forgotten Empire: The World of Ancient Persia, The British Museum Press, London, U.K., Pg. 150.

- 4 Clement Huart (1927), Ancient Persia and Iranian Civilization, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 80.

- 5 Robert William Rogers (1929), A History of Ancient Persia: From its Earliest Beginnings to the Death of Alexander the Great, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, USA, Pg. 16.

- 6 Clement Huart (1927), Ancient Persia and Iranian Civilization, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 81-82.

- 7 Eric Orlin (2016), Routledge Encyclopedia of Ancient Mediterranean Religions, Routledge, New York, USA, Pg. 139.

- 8 William H. McNeil, Jerry H. Bentley, David Christian et al. (2010), Berkshire Encyclopedia of World History, Berkshire Publishing Group, Massachusetts, USA, Pg. 370.

- 9 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): https://www.ancient.eu/Marduk/: Retrieved: 22-02-2019

- 10 The Catholic Encyclopedia (Online Version): http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10402a.htm: Retrieved: 22-02-2019

- 11 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/topic/Anahiti: Retrieved: 22-02-2019

- 12 Encyclopedia Iranica (Online Version): http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/anahid#pt2: Retrieved: 22-02-2019

- 13 A. Carnoy (1918), Journal of the American Oriental Society: The Iranian Gods of Healing, American Oriental Society, Michigan, USA, Vol. 38, Pg. 294.

- 14 Albert J. Carnoy (1917), The American Journal of Theology: The Moral Deities of Iran and India and Their Origins, Vol. 21, No. 1, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA, Pg. 58–78.

- 15 A. Carnoy (1918), Journal of the American Oriental Society: The Iranian Gods of Healing, American Oriental Society, Michigan, USA, Vol. 38, Pg. 296.

- 16 Charles Russell Coulter & Patricia Turner (2000), Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities, Routledge London, U.K., Pg. 464-465.

- 17 Richard Foltz (2013), Religions of Iran: From Prehistory to the Present, One World Publications, London, U.K., Pg. 19.

- 18 Shodhganga (Reservoir of Indian Thesis): http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/2039/10/10_chapt er%202.2.pdf: Retrieved: 22-02-19

- 19 Charles Russell Coulter & Patricia Turner (2000), Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities, Routledge London, U.K., Pg. 400.

- 20 William W. Malandra (1983), An Introduction to Ancient Iranian Religion, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, USA, Pg. 76.

- 21 Prods Oktor Skjaervo (2005), Introduction to Zoroastrianism, Published by the Author, Pg. 25.

- 22 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/topic/Zurvan: Retrieved: 02-03-2019

- 23 A. V. Williams Jackson (1932), Researches in Manichaeism with Special Reference to the Turfan Fragments, Columbia University Press, New York, USA, Pg. 3.

- 24 Michael Tardieu (1997), Manichaeism (Translated by M. B. DeBevoise), University of Illinois Press, Chicago, USA, Pg. 1-2.

- 25 A. V. Williams Jackson (1932), Researches in Manichaeism with Special Reference to the Turfan Fragments, Columbia University Press, New York, USA, Pg. 3-7.

- 26 Kodaddad Rezakhani (2014), Mazdakism, Manichaeism and Zoroastrianism: in Search of Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy in Late Antique Iran, Routledge, New York, USA, Pg. 2.

- 27 Farhad Saboorifar (2017), Mazdakism and its Historical Principals, Institucion Universitaria Salazar Y Herrera, Antioquia, Columbia, Pg. 2480.

- 28 Paul Luttinger (1921), The Open Court: Mazdak, South Illinois University, Illinois, USA, Pg. 671-672.

- 29 Robert William Rogers (1929), A History of Ancient Persia: From its Earliest Beginnings to the Death of Alexander the Great, Charles Scribner’s Sons, London, U.K., Pg. 17.

- 30 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): https://www.ancient.eu/zoroaster/: Retrieved: 23-02-2019

- 31 The Jewish Encyclopedia (Online Version): http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/15283-zoroastrianism: Retrieved: 23-02-2019

- 32 Maneckjee Nusservanji Dhalla (1938), History of Zoroastrianism, Oxford University Press, London, U.K., Pg. 13.

- 33 David Leeming (2005), The Oxford Companion to World Mythology, Oxford University Press, Oxford, U.K., Pg. 411.

- 34 Robert S. Ellwood and Gregory D. Alles (2007), The Encyclopedia of World Religions, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 485.

- 35 Edward Craig (1998), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Routledge, New York, USA, Vol. 9, Pg. 9168.

- 36 H. K. Mirza (1977), The Zoroastrian Religion, Bombay, India, Pg. 109-113.

- 37 Richard Foltz (2010), Journal of Human-Animal Studies: Zoroastrian Attitudes towards Animals, Brill, Leiden, Netherlands, Pg. 370-372.

- 38 Christopher M. Moreman (2018), The Routledge Companion to Death and Dying, Routledge, New York, USA, Pg. 87-92.

- 39 Edward Craig (1998), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Routledge, New York, USA, Vol. 9, Pg. 9168.