Religious Rituals of Ancient Egypt – Worship, Temples & Magic

Published on: 11-Jul-2024(Cite: Hamdani, Mufti Shah Rafi Uddin & Khan, Dr. (Mufti) Imran. (2020), Religious Rituals of Ancient Egypt, Encyclopedia of Muhammad  , Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 493-513.)

, Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 493-513.)

Religion was an important part of the life of the ancient Egyptians. Worshipping the living and the deceased kings, and celebrating their stories in art and onstage were only a few of the religious rituals of the ancient Egyptians. These rituals were the nucleus of their religious life and most of them were performed inside their temples.

Modern religions such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, also have religious rituals. E.g. going to a synagogue, church or mosque and reciting passages from the holy books, but the entire religion is dependent on the belief in God. Like Islam, Christianity and Judaism were also divinely revealed religions, but the last two were modified and corrupted by humans hence Islam is the only one which remains pure and prominent. A person who fails to perform these rituals can still claim to be following that religion as long as he or she believes in it. The Egyptians, however, saw this very differently. To them, believing in the gods was a given faith, as no one questioned their existence. Secondly, they didn’t have any sacred or holy texts like the Torah, New Testament, or Quran, nor did they venerate any divinely inspired list of religious principles. They expressed their faith through their actions—namely, rituals that honored, appeased, or sought to communicate with the gods.

Temples of Ancient Egypt

The Egyptians believed that the living, the dead, and the gods all had the same basic needs—shelter, food and drink, washing, rest, and recreation. The living was accommodated in houses, the dead were provided with tombs, and the gods resided in temples. Food was supplied for the dead by means of the funerary cult, and the god’s needs were met through the divine rituals which ultimately meant that their gods were needy. Once performed within certain areas of the temple, they are still depicted and preserved in the scenes carved and painted on many of the interior walls of the temple. The temple would assume all the spiritual potency of the original “Island of Creation,” the location it sought to re-create, and the rituals depicted in the wall scenes would through magic continue to be performed on behalf of the god even if the rites were discontinued at any time. 1

In all the temples royal offerings were made to the divinity of the locality, and none but the priestly personages attached to the temple itself had free access to its precincts. But the image of god and those of the divinities associated with him were often brought out in solemn processions, in which the entire population took part. 2

The temples were designed to last forever; they were therefore built of stone. Egyptologists of the nineteenth century categorized temples as “divine,” or “cultus”—designating that the resident deity was worshiped by means of regular rituals carried out by the king or priest—or “mortuary”—where the king or priest performed rituals for a resident deity plus the dead, deified ruler who had built the temple, together with all the previous legitimate rulers, who were known as the “Royal Ancestors.”

However, modern scholarship indicates that this division was misleading because it inferred that each type of temple was limited either to the cult of a god or king. It also suggested that the recipient of the mortuary rituals was not divine and presupposes that the Egyptians themselves clearly distinguished between cultus and mortuary temples, which they did not. Both types of temples had varied and interwoven functions, and such a division and categorization now appear to be too simplistic. Egyptologists, therefore, now generally use the term ‘cult complex’ for all cultic enclosures and structures, and for more specific purposes, they replace the terms mortuary temple with royal cult complex and divine or cultus temple with divine cult complex. 3

The following were the major temples of Ancient Egypt:

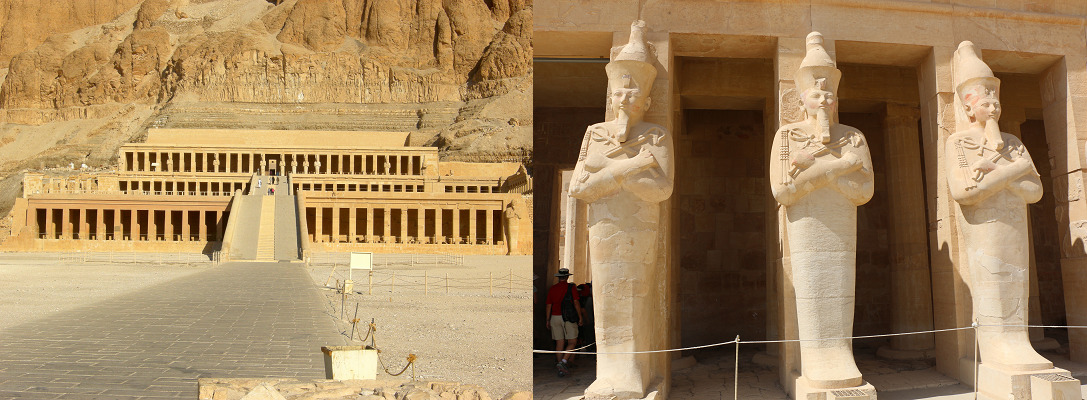

Temple of Hatshepsut

At the foot of the hills and towering cliffs, which form the background of the Theban plain on the western side of the river, extends a long line of temples - the funerary temples of the great emperors of the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties. These splendid buildings, however, were not only intended to provide for the posthumous welfare of the Pharaohs who erected them, but they were also dedicated to the worship of the State-god, Amun. Apart from the actual temple buildings, the sacred precincts included gardens and orchards, ornamental lakes, storehouses, cattle-sheds, the dwellings of the priests, and the quarters of the numberless slaves, mostly foreign captives, who worked on the temple estates as agricultural labourers or herdsmen, or as masons, joiners, and the like.

The most famous, and probably the most beautiful, of all the royal funerary temples was that of Queen Hatshepsut, which, like all the others, was dedicated to the worship of Amun, but also contained chapels of Anubis, the tutelary god of the dead, and the goddess Hathor, in whose cult women figured so prominently. 4

Temple of Osiris

There was a major shrine of Osiris in Abydos, now called Kom el-Sultan by the Egyptians. There were many sites of worship dedicated to Osiris in the Nile Valley and beyond, but the god’s main cultic temple was located in Abydos, the city dedicated to him. Only the ramparts of the temple are visible today. A limestone portico erected by Ramesses (1290–1224 B.C.) is also evident. The temple, called the Osireion in some records, dates to the Third Dynasty (2649–2575 B.C.) or possibly earlier.

Temples at Karnak

Karnak contains the northern group of the Theban city temples, called in ancient times as Ipet-Isut, “Chosen of Places.” The ruins cover a considerable area and are still impressive, though nothing remains of the houses, palaces, and gardens that must have surrounded the temple precinct in ancient times. The most northerly temple is the Temple of Mont, the war god, of which little remains now but the foundations. The southern temple, which has a horseshoe-shaped sacred lake, was devoted to the goddess Mut, wife of Amon; this also is much ruined. Both temples were built during the reign of Amenhotep III (1390–53), whose architect was commemorated by statues in the Temple of Mut. Between these two precincts lay the largest temple complex in Egypt, and one of the largest in the world, the great metropolitan temple of the state god, Amon-Re. It has been called a great historical document in stone: in it are reflected the fluctuating fortunes of the Egyptian empire. There are no fewer than 10 pylons, separated by courts and halls, and nowadays numbered for convenience, number one being the latest addition. Pylons one through six form the main east-west axis leading toward the Nile. The seventh and eighth pylons were erected in the 15th century B.C. by Thutmose III and Queen Hatshepsut, respectively, and the ninth and tenth during Horemheb’s reign (1319–1292). These pylons formed a series of processional gateways at right angles to the main axis, linking the temple with that of Mut to the south and, farther, by way of the avenue of sphinxes, with the temple at Luxor 2 miles (3 km) away. 5

Priests

Economic records indicate that the priesthood was a major institution in Egyptian society. In contrast to the many written records and the statues of priests that survive from the dynastic period virtually, no visual record of priests remains in the temples. 6 The king of Egypt was the high priest of every god, and in all important ceremonies, he alone was depicted in the temple scenes as the officiant. For practical purposes, however, he delegated his functions to the particular professional local priesthoods. In due course the priests, courtiers, and officials shared in his divine powers and privileges. Even though they only acted on behalf of the divine ruler, his representatives shared in some measure his personality and potency. But texts make it clear that many priests were actually engaged in the temple workings as proxies for the king. 7

Ancient Egyptian priests were fully integrated into all aspects of society. They lived in the villages, married, and had children. The ancient Egyptian priest, was not expected to serve as an example of religiously dictated behavior. As one Ptolemaic text exhorts, “oh brother and husband, priest of Ptah, never cease drinking, eating, becoming intoxicated, making love, passing the time in merriment, following your heart day and night.” Most priests were expected to serve the gods only part-time; they could revert to other professions, whether in government service or in the trades, when they were not at the temple.

Types of Priests and their Duties

Priests were organized into many different ranks, each with specific duties and privileges and having varying levels of access to parts of a temple. Some ranks worked in the temples, others worked exclusively in funerary establishments, and a few apparently worked in both spheres. A priest could serve several deities at the same time. Priests were assisted by semdet, a nonpriestly workforce who acted in support of the temple as farmers, sailors, shipbuilders, or gold washers. Priests could be fired from their jobs.

Descriptions of the most important ranks of priests are as follow:

Wab

The majority of priests held the title wab, ‘pure one,’ which was the entry-level position in the priesthood. There were regular wabs and ‘great wabs’. Numerous wabs were associated with each institution. Many priests of other ranks started as wabs and worked their way up to more prestigious titles. This rank of priest wore no distinguishing dress or hairstyle. They served in both temples and tombs. In the mortuary context, the wab was responsible for carrying offerings in the funeral, and thereafter for periodically supplying the tomb chapel with additional offerings.

Inside the temples, wabs were charged with carrying offerings, and they are frequently listed among the personnel involved in the daily offering service. However, the wabs’ low level of purity meant that they had only limited access to the inner portion of a temple. Despite their low rank, wab priests carried the sacred boat of the god during oracles. This was an important and delicate point of contact between the temple and the larger community, for it was the wabs who perceived (and controlled) the movement of the boat, which was interpreted as the god’s approval or rejection of a petition. 8

Hem-Ka

The Hem Ka was responsible for the periodic offerings presented at the tomb. This duty and the provision of continuous service was a serious and necessary consideration, usually carried out with support provided by endowments from the deceased and her family. The priestly disciplines of scribal scholarship, purification, magic, divination, and healing all coalesce in the role of the Hem Ka. His specific task was to ensure the peace of the deceased-and the family- through the performance of continuous prayer and offering ceremonies. Physical nourishment at the tomb is believed by metaphysicians to form the ecto-plasmic basis for materializations of the Ka, or "ghost." In this manner, the Egyptians expected the Ka to return after its flight through the shadow worlds to the tomb seeking this nourishment, so that it could preserve its bonds with the physical world and manifest when summoned.

The Hem Ka was also required to know the spells which magically brought sustenance to the deceased, an act as important as receiving the physical offerings. The recitation of formulae for ensuring all manner of food and drink had to be executed at the proper times and in the appropriate manner to ensure the continuance of the name and the Ka. An example of the necessity believed by the Egyptians for the services of the Hem Ka is found in a widely circulated tale of a priest haunted by a restless spirit in ancient times. 9

Lector Priest (Khery Hebet)

Lector priests were distinguished by their ability to read, and their main duty was to recite specialized religious texts in both temple and mortuary rituals. The lector wore a distinctive sash that crossed from the shoulder to the hip. In the Old Kingdom, lectors were often members of the royal family, a sign of the prestige of this profession, but by the Middle Kingdom, the pool of eligible candidates had widened to include any literate man. Because they were literate, this class of priest was considered to be the keeper of specialized knowledge.

Lectors were an important part of the funeral service, as they were responsible for reciting the spells that guided the soul of the deceased from the time of death to its transition to an akh (transfigured spirit). In scenes of funerals, the lector is shown accompanying the coffin, often holding a papyrus from which he will read. Lectors also played a crucial role in Egypt’s administration. Texts that refer to the coronation of the king state that the lector priest was responsible for the announcement of the prenomen (the name pharaoh assumed on accession to the throne).

God’s Father (It Netcher)

The class of priest known as God’s Fathers wore no distinctive garb. They are mentioned in both temple and mortuary contexts, where they participated with other priests in the daily offering service and the offering for the soul of the deceased. Arranged in hierarchies bearing the ranks of First, Second, and Third God’s Father, they are most commonly associated with the cult service of Min, Amun, and Ptah. The title is commonly encountered in New Kingdom temple administration texts (often with that of wabs and lector priests). God’s Fathers were known from the Old Kingdom when the title was associated with men who were related to the royal family, being the father-in-law of the king, or more rarely, a son-in-law. By the late 18th Dynasty, the title designated a specific type of priest and no longer meant that the holder was a member of the royal family. In New Kingdom administrative texts, God’s Fathers are associated with the delivery of food and supplies to the temple and the inspection of temple property.

Sem Priest

The sem was recognizable by his leopard-skin robe and by his hair, which was worn in a distinctive side-lock. Sem priests are mentioned from the Early Dynastic era onward. They are attested in both funerary and temple contexts. Some sem priests were attached to specific gods; we have references to the sem of Anubis and of Khnum. The title could also be combined with other priestly titles. The sem presided over the Opening of the Mouth ritual at a funeral, in which he touched the face of the mummy with tools to revive the senses of the deceased in the afterlife. He performed the same ritual on statues, imbuing them with the spirit of the person they depicted and enabling them to act as surrogates for the one who commissioned the image.

Iwnmutef Priest

The Iwnmutef priest used to wear the same leopard-skin robe and side-lock as the Sem. The name of this rank of funerary priest meant, “Pillar of his mother,” perhaps a reference to his supporting the sky goddess whose body formed the vault of heaven. Iwnmutefs were associated with both private and royal mortuary cults. 10

Priestess

The priesthood was run by men, but a few temples dedicated to goddesses had priestesses. Even royal women could act as priestesses through a position known as Divine Wife of Amun. 11 In the Old Kingdom, there were female hem netcher known as hemet netcher, who served the goddesses Hathor and Neith. In the Middle Kingdom, a few women served as hemet netcher of the gods Amun, Ptah, and Min, and as wabets (female wab). Priestesses were divided into hierarchies similar to the men.

Female priestly roles were downgraded in the New Kingdom and the Third Intermediate Period. During those periods, women were almost exclusively singers (shamyet or heset) in divine choirs that accompanied priests in processions around and through the temple; the higher ranks apparently followed the priests into the area near the sanctuary. Women bore titles such as “Singer in the Temple of Amun,” or the more prestigious “Singer in the Interior of the Temple of Amun.” They were under the supervision of a male or female “Overseer of the Singers.” Other women appear as singers of Osiris, or dancers of the “Foremost of the Westerners” (i.e., Osiris) or Min.

The erosion of female sacral titles was obvious in the Third Intermediate Period, an era in which many monuments were commissioned by women, or at least commemorated women. Among a group of forty-nine stelae dating to this period, only eleven lists a woman who bears a priestly title; most of the women listed either have no title or are simply referred to as “Mistress of the House.”

The title God’s Wife (also hemet netcher, but a different word than for the priestess’s title mentioned earlier), which denoted a priestess of Amun in the Third Intermediate Period, was first attested several times in the Middle Kingdom. It appeared more consistently in the early New Kingdom, when it was associated with queens and other royal women. In this early period, it may have been more closely related to succession than to any sacred function, but by the Third Intermediate Period, the post took on a new meaning, and the god’s Wife was charged with supervising the holdings of Amun in Thebes. In this era, the god’s Wife became immensely wealthy and influential. As a part of her cultic role, she was thought to stimulate and please Amun, thereby evoking the concept of rejuvenation and rebirth. These types of concepts were coined by ancient and even contemporary pseudo religious scholarship to ensure that they could satisfy their carnal desires with the women they liked in the name of religion so that nobody could stop or even defame or punish them. On the contrary, they would be venerated for their heinous acts. These types of theories also gave young women a license to copulate with whomever they liked and destroy the moral fabric of the society in the name of religion.

Dreams and Oracles

All Egyptians believed that dreams were visions from the gods, but the message was not always easy to understand. In such a case the puzzled person could repeat the dream to a priest specially trained to interpret dreams’ meanings. The priest had many books to help him find the answer.

In difficult cases where there was a problem in the family or a dispute that neither side could agree on, it was usual to consult an oracle. This was done by asking a temple scribe to write down the question and receive a “yes” or “no” answer from the god when it was presented to the priests. On feast days an inquirer might ask the god directly when he appeared on his sacred barque outside the temple wall. Answers were given by the boat swaying backward, forward, or dipping. 12

On festival days, the statues of the gods were carried through the streets of the cities or floated on barges to the local shrines and necropolis regions. The people flocked to the processions, anxious for the statues to reach the Stations of the Gods that were erected on street corners. These stations were small stages, slightly elevated so that the people could view the statue of the deity on display. There the gods were asked questions about the future, and the devoted faithful, in turn, received ritualized and traditional responses. The statue of the god moved on its pedestal or in its shrine in response to questions, or the entire shrine swayed to one side or another when the queries were posed to it. A movement in one direction indicated a negative response, and a movement in another direction provided a positive reply. Such acts were nothing more than a circus show through which the priests would establish their authority for being connected with the gods. This way, they were respected more and were also given additional gifts and wealth for their services.

In some cult centers the statue “spoke” to the faithful, as priests could be hidden within the shrine and could provide a muffled but audible response. Some of these priests offered sermons to the people as the “mouth of the god” and repeated time-honored wisdom texts for the edification of the spectators.

The sacred Bulls of Egypt, the Theophanies of some deities, were also used as oracles in their own temples. An animal was led into a vast hall crowded by faithful onlookers. The people posed their questions and the bull was loosed. Two doors opened onto chambers containing the bull’s favorite food in order to elicit a response. One door signified a negative response to the question posed at the time and the other a positive reply. The bull entered one chamber or another, thus rendering its divine judgment on the matters under discussion.

The most famous oracle in Egypt was in Siwa Oasis, located 524 miles northwest of modern Cairo. The temple at Aghurmi in the Siwa Oasis had an ancient oracle site that was used by pilgrims. The temple of Umm Ubayd also had an oracle that welcomed visitors in all eras. 13

Daily Temple Rituals

One group of temple rituals was enacted on a daily basis, and these followed the same pattern for all temple gods throughout the country. The daily temple ritual was carried out in all divine and royal cult complexes from at least as early as Dynasty 18. It provided a ritualized and dramatized version of the mundane processes of washing, clothing, and feeding the god’s cult statue in the sanctuary. The priest (acting as the king’s delegate) entered the sanctuary each morning and lifted the god’s statue out of its box shrine, and placed it on the altar immediately in front. He then removed its clothing and makeup of the previous day, before fumigating the image with different kinds of incense and presenting it with balls of natron (which the Egyptians chewed in order to cleanse the breath). The priest then dressed the statue in fresh clothes, decorated its face with makeup, and presented it with jewelry and insignia. Finally, he gave the god the morning meal and withdrew backwards from the sanctuary. He presented two other meals at noon and in the evening before replacing the statue in the box shrine.

This ritual included elements from the mythologies of Re and Osiris and was intended to revitalize the god and reaffirm his daily rebirth. Negligience of these duties would, it was believed, ensure the return of chaos, the state that had prevailed before the universe was created. Correct observance of the rites would, however, be rewarded by divine favor: Temple religion, based on a compact between gods and men, ensured that the gods received temples, food, and other offerings, and booty from military campaigns in return for their gifts of power, fame, immortality, and success in battle for the king and fertility, peace, and prosperity for Egypt and its people.

From the New Kingdom onward another ritual was performed in the royal cult complexes at the conclusion of the Daily Temple Ritual. Known as the “Ritual of the Royal Ancestors,” this attempted to ensure that the former legitimate kings of Egypt gave their support to the reigning king. After his death this ruler would join them, and so the ritual also sought to gain benefits and eternal sustenance for him.

The food was removed from the god’s altar at the conclusion of the daily temple ritual and taken to another area of the temple. After some preliminary rites it was offered to the ancestors (usually represented in the temple in the form of a list of kings inscribed on a wall). The food was subsequently removed intact from this altar and taken outside the temple to be divided among the priests as their daily payment. In the divine cult complexes this division took place immediately after the Daily Temple Ritual. 14 These sacrificial and other religious ceremonies were mostly held so that the so-called religious class could get their hands on the wealth and food of the people since these ceremonies served no religious purpose. Still they continued with these practices so that they could maintain their respect in the society and enjoy a luxurious lifestyle. In that society, the priest was respected to the extent that even the elite considered it an honor if a priest deflowered their virgin daughter in the name of religious ceremony.

Purification Practices

Purification practices and rituals were an important part of ancient Egyptian worship. Incense was burned prior to temple ceremonies and rituals in order to purify the air. Most priests ritualistically washed themselves as often as four times a day (twice at night and twice during daylight hours) in order to purify themselves for temple work. Indeed, the word for the type of priest most numerous in a temple was the wab, or “purified,” priest. Such priests also shaved all of the hair on their heads and bodies, kept their nails cut short, rinsed their mouths in a natron (salt) solution, and followed rigid rules regarding what they could eat, drink, wear, and do prior to engaging in religious ceremonies.

Ritual washing was conducted in a temple’s sacred lake, if it had one, or in rectangular or T-shaped limestone troughs. Such troughs have been found not only in temple complexes but also near smaller temples and shrines. Purification or cleansing rituals were probably conducted in households as well, since ancient Egyptian texts mention women engaging in such activities after childbirth and menstruation. In fact, the ancient Egyptian word for menstruation, hesmen, also means ‘to purify oneself.’

In addition, a few New Kingdom texts mention that eating fish caused a person to be impure, so households might have been subjected to dietary taboos prior to purification rituals. The most important function of purification rituals and practices, however, was still in the domain of priests: to make spells and rituals more powerful. Indeed, ancient Egyptian magical texts suggest that certain spells and rituals would not work at all unless the person performing them was in a purified state. 15

Iru - Ceremonies of the Sky

The creative worlds became accessible through the rhythms of cosmic life-the Solar, Lunar, and Stellar resonances of the sacred astronomy. These rhythms provided the powers of the temple and renewed them cyclically. The Iru (fabrications) were temple observances that took place during these times-at the New Moon and Full Moon (Lunar), Solar ingresses, solstices, and equinoxes (Solar), and Stellar events such as the heliacal rising of Sirius or the return of the temple's particular star to the pre-dawn sky. Also included in these ceremonies were any events that denoted the inception of new cycles, such as the Wag festival for the beginning of the Lunar New Year. The times for observing these ceremonies may vary each year and must be calculated using the temple's system of sacred astronomy.

The function of the Iru was to capture the outpouring of the Neter as it was released cosmically, and direct it to enhance human and natural life. In the Egyptian world view, divine life was believed to be resident in all phenomena, and existed in its most powerful form in celestial bodies, where even the souls of exalted human beings could journey. 16

Ritual Sacrifices

The most widespread and important ritual out of many consisted of offerings and sacrifices to the gods. These could take the form of liquids such as milk, honey, or wine, which were set before or poured over an altar stone. Flowers and other kinds of plants were also offered. More common, however, were animal sacrifices. Cows, goats, sheep, or other creatures were slaughtered and parts of them burned on an altar. It was thought that the smoke from the burning beast rose up into the sky and provided one or more gods with welcome nourishment. This ceremony and the theory behind it were repeated century after century not only in Egypt but in lands across the ancient world.

Herodotus had witnessed such rituals in his native land, and after visiting Egypt, he made sure to describe the local version in his book so that his Greek readers could compare it with their own practices. Egyptians who desired to perform a sacrifice, he wrote, would take an animal to an appropriate altar and light a fire. Then, after pouring a liquid offering of wine on the altar, they butchered the creature, sliced off its head, and cut up the carcass. Having finished slaughtering the animal, he continued, they first pray, and then take its belly out whole, leaving the intestines and fat inside the body. Next, they cut off the legs, shoulder, neck, and rump, and stuff the carcass with loaves of bread, honey, raisins, figs, frankincense, myrrh, and other nice-smelling substances. Finally, they poured a quantity of oil over the body and burned it. They always fasted before a sacrifice, and while the fire was consuming it, they beat their breasts.

Another type of sacrificial gift to the gods—known as a votive offering— was not meant to feed or pacify a deity. Instead, someone made a votive offering either in exchange for a god doing that person a favor or to thank the divinity for answering a prayer. Such offerings sometimes consisted of flowers, food, and/or beverages. Other common votive gifts included wooden, metal, or pottery statuettes of deities or pharaohs.

People placed votive offerings on altars or in other spots where it was thought that the gods might notice them. It was also accepted practice to carve or paint a request for a divine favor onto a wooden or stone slab called a stelae. In the mid-second millennium B.C., worshippers started drawing or carving human ears onto stelae based on the notion that this would help a god hear the message. 17

Human Sacrifice

Human sacrifice was practiced as part of the funerary rituals associated with all of the pharaohs of the first dynasty. Nancy Lovell, who has examined the skeletons from some of these subsidiary burials, suggests that their teeth show evidence of death by strangulation. Perhaps officials, priests, retainers and women from the royal household were all sacrificed to serve their king in the afterlife. The tomb of Djer has the most subsidiary burials, and it is in general the later royal burials that have fewer ones. For unknown reasons, the practice seems to have been discontinued after the 1st Dynasty, and in later times small servant statues and then shabtis (funerary figurines) may have become more acceptable substitutes. 18

Mortuary Rituals

These were the ceremonies and elaborate processes evolving over the centuries in the burial of ancient Egyptians. Such rituals and traditions were maintained throughout the nation’s history, changing as various material and spiritual needs became manifest. In the Pre-dynastic Period (before 3000 B.C.), the Egyptians, following the customs of most primitive cultures of the area, buried their dead on the fringes of the settlement region, in this case the surrounding deserts. This custom was maintained for some time in Upper Egypt, but in Lower Egypt the people appear to have buried their dead under their houses as well.

The corpses of the Pre-dynastic Periods were normally placed in the graves on their left sides, in a fetal or sitting position. The religious texts of later eras continued to extort the dead to rise from their left sides and to turn to the right to receive offerings. The graves were also dug with reference to the Nile, so that the body faced the West, or Amenti, the western paradise of Osiris. By the time Egypt was unified in c. 3000 B.C., the people viewed the tomb as the instrument by which death could be overcome, not as a mere shelter for castoff mortal remains. The grave thus became a place of transfiguration. The A’akh, the transfigured spiritual being, emerged from the corpse as a result of religious ceremonies. The A’akh, the deceased, soared into the heavens as circumpolar stars, with the goddess Nut. As the Pyramid Texts declared later: “Spirit to the sky, corpse into the earth.” All of the dead were incorporated into cosmic realms, and the tombs were no longer shallow graves but the “houses of eternity.”

The desert graves had provided a natural process for the preservation of the dead, something that the mastabas altered drastically. Corpses placed away from the drying sands, those stored in artificial graves, were exposed to the decaying processes of death. 19 The commoners and the poor, however, conducted their burials in the traditional manner on the fringes of the desert and avoided such damage. The priests of the various religious cults providing funerary services and rituals discovered the damage that was being done to the corpses and instituted customs and processes to alter the decay, solely because the ka and the BA could not be deprived of the mortal remains if the deceased was to prosper in the afterlife.

Reserve Heads (stone likenesses of the deceased) were placed just outside the tombs so that the spiritual entities of the deceased could recognize their own graves and return safely, and so that a head of the corpse would be available if the real one was damaged or stolen. The elaborate mastabas erected in Saqqara and in other necropolis sites and the cult of Osiris, the Lord of the Westerners, brought about new methods of preservation, and the priests began the long mortuary rituals to safeguard the precious remains. In the early stages the bodies were wrapped tightly in resin-soaked linen strips, which resulted only in the formation of a hardened shell in which the corpses eventually decayed. Such experiments continued throughout the Early Dynastic Period, a time in which the various advances in government, religion, and society were also taking place. Funerary stelae were also introduced at this time. The tombs of the rulers and queens were sometimes surrounded by the graves of servants as well, as courtiers may have been slain to accompany them into eternity.

The embalming of the dead, a term taken from the Latin word which is translated as “to put into aromatic resins,” was called ut by the Egyptians. The word mummy is from the Persian, meaning pitch or bitumen, which was used in embalming during the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.) and probably earlier. In later eras corpses were coated or even filled with molten resin and then dipped in bitumen, a natural mixture of solid and semisolid hydrocarbons, such as asphalt, normally mixed with drying oil to form a paint-like substance. In the beginning, however, the processes were different.

In order to accomplish the desired preservation, the early priests of Egypt turned to a natural resource readily available and tested it in other ways: Natron, as it was found in the Natron Valley near modern Cairo. That substance was also called hesinen, after the god of the valley, or heshernen tesher, when used in the red form. Natron was a mixture of sodium bicarbonate and sodium carbonate or sodium chloride. It absorbed moisture called hygroscopic, and was also antiseptic. The substance had been used as a cleansing agent from early eras on the Nile and then was used as a steeping substance that preserved corpses. The priests washed and purified the bodies and then began to prepare the head of the corpse. The brain was sometimes left intact in the skull but more often, the priest inserted hooks into the nose, moving them in circular patterns until the ethmoid bones gave way and allowed an entrance into the central cavity. A narrow rod with a spoon tip scooped out the brains, which were discarded. Once cleared of brain matter, by use of the hook or by surgical means, the skull was packed with linens, spices, and Nile mud. The mouth was also cleansed and padded with oil-soaked linens, and the face was covered with a resinous paste. The eyes were sometimes filled with objects to maintain their shape and then covered with linen, one pad on each eyeball, and the lids closed over them. The corpse was then ready for the ‘Ethiopian Stone,’ a blade made out of obsidian.

Peculiarly enough, the mortuary priest who used the blade called the “Ethiopian Stone” and performed surgical procedures on the corpses being embalmed, was reportedly shunned by his fellow priest and embalmers. 20 The embalmers removed the organs from the abdomen through a long incision cut into the left side. This process was followed with animals as well as humans. Egyptians regularly mummified their pet cats, dogs, gazelles, fish, birds, baboons, and also the Apis bull, considered an incarnation of the divine. 21

Each period of ancient Egypt witnessed an alteration in the various organs preserved. The heart, for example, was preserved separately in some eras, and during the Ramessid dynasties the genitals were surgically removed and placed in a special casket in the shapes of the god Osiris. This was performed, perhaps, in commemoration of the god’s loss of his own genitals as a result of the attacks by the god Set, or as a mystical ceremony. These jars and their contents, the organs soaked in resin, were stored near the Sarcophagus in the special containers.

The use of natron was involved in the next step of the process. The bodies were buried in mounds of natron in its dry crystal form. When the natron bath had dried the corpse sufficiently, the nails were tied on and finger stalls placed on the corpse. The natron bath normally lasted 40 days or more, producing a darkened, withered corpse. The temporary padding in the cavities was removed and stored in containers for use in the afterlife. The corpse was washed, purified, and dried, and then wads or pads of linen, packages of natron or sawdust, were used to fill the various empty portions of the remains. Aromatic resins were also used to make the corpse fragrant. The outer skin of the mummy, hardened by the natron, was massaged with milk, honey, and various ointments. The embalming incision made in the abdomen was closed and sealed with magical emblems and molten resin. The ears, nostrils, eyes, and mouth of the deceased were plugged with various wads of linen, and in the case of royal corpses the tongue was covered with gold. The eyes were pushed back with pads and closed, and the body was covered with molten resin. The cosmetic preparations that were part of the final stages of embalming included the application of gold leaf, the painting of the face, and the restoration of the eyebrows. Wigs were placed on some corpses, and they were dressed in their robes of state and given their emblems of divine kingship. In some periods the bodies were painted, the priests using red ochre for male corpses and yellow for the women. Jewels and costly amulets were also placed on the arms and legs of the mummies. The actual wrapping of the mummy in linen, took more than two weeks. This was an important aspect of the mortuary process, accompanied by incantations, hymns, and ritual ceremonies.

Throughout the wrappings, semiprecious stones and amulets were placed in strategic positions, each one guaranteed to protect a certain region of the human anatomy in the afterlife. The linen bandages on the outside of the mummy in later eras were often red in color. The mummy mask and the royal collars were placed on the mummies in the last. Linen sheets were glued together with resins or gum to shape masks to the contours of the heads of the corpses, then covered in stucco. These masks fitted the heads and shoulders of the deceased. Gilded and painted in an attempt to achieve a portrait, or at least a flattering depiction of the human being, the masks slowly evolved into a coffin for the entire body. In general whole this process of embalming mummies is considered one of the great artistic and chemical works of the Egyptians, but in reality, it was one of the greatest insults of the dead bodies of their royals.

Additionally, the funeral processions started from the valley temple of the ruler or from the embalming establishment early in the morning. Professional mourners who were paid, called Kites, were hired by the members of the deceased’s family to wear the color of sorrow, blue-gray, and to appear with their faces daubed with dust and mud, signs of mourning. These professional women wailed loudly and pulled their hair to demonstrate the tragic sense of loss that the death of the person being honored caused to the nation. Servants of the deceased or poor relatives who owed the deceased respect headed the funeral procession. They carried flowers and trays of offerings, normally flowers and foods. Others brought clothes, furniture, and the personal items of the deceased, while the Shabtis and funerary equipment were carried at the rear. The shabtis were small statues in the image of the deceased placed in the tomb to answer the commands of the gods for various work details or services. With these statues available, the deceased could rest in peace.

Boxes of linens and the clothes of the deceased were also carried to the tomb, along with the canopic jars, military weapons, writing implements, papyri etc. The Tenkenu was also carried in procession. This was a bundle designed to resemble a human form. Covered by animal skins and dragged on a sled to the place of sacrifice, the tekenu and the animals bringing it to the scene were ritually slain. The coffin and the mummy arrived on a boat, designed to be placed on a sled and carried across the terrain. When the coffin was to be sailed across the Nile to the necropolis sites of the western shore, two women mounted on either side. They and the kites imitated the goddesses Isis and Nephthys, who mourned the death of Osiris and sang the original Lamentations.

If the mummy was of a ruler or queen, the hearse boat used for the crossing which had a shrine cabin adorned with flowers and with the palm symbols of resurrection. During the crossing, the sem priest incensed the corpse and the females accompanying it. The professional mourners sometimes rode on top of the cabin as well, loudly proclaiming their grief to the neighborhood. The procession landed on the opposite shore of the Nile and walked through the desert region to the site, where the sem priest directed the removal of the coffin so that it could be stood at its own tomb entrance for the rituals.

The priest touched the mouth of the statue or the coffin and supervised the cutting off of a leg of an ox, to be offered to the deceased as food. All the while the Muu Dancers, people who greeted the corpse at the tomb, performed with harpists, the hery-heb priests, and ka priests, while incensing ceremonies were conducted. The mummy was then placed in a series of larger coffins and into the sarcophagus, which waited in the burial chamber inside. The sarcophagus was sealed, the canopic jars put carefully away, and the doors closed with fresh cement. Stones were sometimes put into place, and seals were impressed as a final protection. A festival followed this final closing of the tomb.

Once the body was entombed, the mortuary rituals did not end. The royal cults were conducted every day, and those who could afford the services of mortuary priests were provided with ceremonies on a daily basis. The poor managed to conduct ceremonies on their own, this being part of the filial piety that was the ideal of the nation. They also believed that the name of the deceased had to be invoked on a daily basis in order for that person to be sustained even in eternity. 22

Worship

Worship of each of the hundreds of ancient Egyptian gods – regardless of geography or function – was the same throughout the temples of Egypt. Worship in the home was similar except that rituals were carried out by the family rather than priests. The statue of the god was placed within a sanctuary in the rear of the temple, and the priest entered this sanctuary twice a day (at dawn and at dusk) to carry out the rituals.

At dawn, the priest removed the statue from the shrine, washed it, anointed it with perfumes and ointments, and dressed it in a fresh linen shawl. The deity was then offered food and drink, which were placed at his or her feet. After the deity had taken spiritual nourishment from the food, it was distributed among the priests within the temple.

At dusk, the same rituals were repeated and the statue was put to bed. The statue was washed, anointed with perfumes and ointments, offered food and drink, again which was placed at his or her feet. This was removed after the deity had taken spiritual nourishment from it. Then the statue was placed inside the shrine until the morning, when the rituals started again. Throughout these rituals, the priest recited prayers and incantations, which varied in nature depending on the deity and his or her role. 23

Festivals

Festivals were an important part of ancient Egyptian life. Prior to each New Year, a group of priests known as Hour priests, associated with the House of Life (an institution where sacred texts were written and stored), used astronomical observations to determine the festival calendar for the upcoming year. Festivals featured a great deal of eating, drinking, offerings and perhaps sacrifices to the gods, dancing, music, and various forms of entertainment, such as performances by acrobats. In many cases, a statue of the deity being honored by the festival was paraded through the streets hidden within a small portable shrine.

The most important ancient Egyptian festivals often attracted pilgrims from throughout the country. For example, according to the Herodotus, more than seven hundred thousand people attended a festival in Bubastis dedicated to the goddess Bastet. Thousands more attended a festival in Abydos each year that was dedicated to the god Osiris, with some participants marking their annual attendance by adding an inscription to a family stela at the site. Other festivals were held monthly or biannually rather than annually. For example, beginning in the Old Kingdom, the appearance of each new moon marked a festival day, and twice a year the Nile River was honored with its own festival, during which flowers were floated on its surface. 24

Joyous Union

In the season of Het-Her, the fecundity that is released from the soil in the early spring was celebrated in The Festival of the Joyous Union. The energy dynamic of Taurus, the sign of Fixed Earth, was embodied in the image of the fertile goddess, who joined with her consort at the commencement of the growing season. The union of Sun and Moon in her crown symbolized, among other things, the fusion of the active life principle (the Sun) with the passive soil (the Moon), which together inaugurated the cycle of proliferation in the natural world (the New Moon). Het-Her's realm of creative expression-art, music, dance, and performance became accessible through this observance. She also gave boon to affairs of the heart and relationships at a distance that await reuniting. The Festival of the Joyous Union conjoined all polarities and encouraged the conception of meaningful endeavors, events that bore fruit and continued to proliferate. It ignited the atmosphere of devotion, commitment, and celebration, being an appropriate festival for weddings, engagement, or hand-fasting. 25

Osiris Mysteries

These were the annual ceremonies conducted in honor of the god Osiris, sometimes called the Mysteries of Osiris and Isis, passion plays, or morality plays, and staged in Abydos at the beginning of each year. They were recorded as being observed in the Twelfth Dynasty (1991–1783 B.C.) but were probably performed for the general populace much earlier. Dramas were staged in Abydos, with the leading roles assigned to high-ranking community leaders or to temple priests. The mysteries recounted the life, death, mummification, resurrection, and ascension of Osiris, and the dramas were part of a pageant that lasted for many days. Egyptians flocked to the celebrations. After the performances, a battle was staged between the followers of Horus and the followers of Set. This was a time-honored rivalry with political as well as religious overtones. Part of the pageant was a procession in which a statue of Osiris, made out of electrum, gold, or some other precious material, was carried from the temple. An outdoor shrine was erected to receive the god and to allow the people to gaze upon the beautiful one. There again Osiris was depicted as rising from the dead and ascending to heavenly realms. 26

Opet

Each year, the cult images of Amun-Ra, Mut, and Khonsu (and perhaps of the king too) were taken in their barque shrines from Ipetsut to Luxor in a great procession, either by land or by river. As the statues were paraded through the streets on the shoulders of priests, the population thronged to catch a glimpse of these sacred objects and to receive their blessing. The Opet Festival was an occasion for much jubilation and feasting, and a welcome break from the daily grind. But like everything else in ancient Egypt, it was designed not for the people but for the king. Once safely inside the precinct of Luxor Temple, the cult images were taken from their barque shrines and installed in their new quarters. The king, then entered the sanctuary to commune in private with the image of Amun-Ra.

After a time, the king emerged into the hall of appearance, to receive the acclaim of priests and courtiers gathered together for the occasion. (Special hieroglyphs at the base of columns directed the common people to the sanctioned viewing places.) His transformation was clear for all to see (and one assumes nobody would have dared to remark on the emperor’s new clothes). Through his communion with the king of the gods, the monarch himself had been visibly rejuvenated, his divinity recharged. He had become the living son of Amun-Ra. The key to the whole ceremony was the royal ka, the divine essence that passed, unseen, into the mortal body of each successive monarch and made him godlike. 27

Wepet-Renpet

This was the New Year's Day celebration in ancient Egypt. The festival was a kind of moveable feast as it depended on the inundation of the Nile River. It celebrated the death and rebirth of Osiris, and by extension, the rejuvenation and rebirth of the land and the people. It is firmly attested to as initiating in the latter part of the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613 - c. 3150 B.C.) and is clear evidence of the popularity of the Osiris cult at that time.

Feasting and drinking were a part of this festival, as they were for most, and the celebration would last for days; the length varied depending on the time period. Solemn rituals related to the death of Osiris were observed as well as singing and dancing to celebrate his rebirth.

Bast

This was the celebration of the goddess Bastet at her cult center of Bubastis and another very popular festival. It honored the birth of the cat goddess Bastet who was the guardian of hearth and home and protector of women, children, and women's secrets. Herodotus claims that Bastet's festival was the most elaborate and popular in Egypt. Egyptologist Geraldine Pinch, citing Herodotus, claims, ‘women were freed from all constraints during the annual festival at Bubastis. They celebrated the festival of the goddess by drinking, dancing, making music, and displaying their genitals’. This raising of the skirts by the women, described by Herodotus, exemplified the freedom from normal constraints often observed at festivals but, in this case, also had to do with fertility.

Min

Min was the god of fertility, virility, and reproduction from the Pre-dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 6000 - c. 3150 B.C.) onwards. He was usually represented as a man standing with an erect penis holding a flail. The Min Festival was probably celebrated in some form starting in the Early Dynastic Period but is best attested to in the New Kingdom and afterwards.

As at the Opet Festival, the statue of Min was carried out of the temple by the priests in a procession, which included sacred singers and dancers including girls. When they reached the place where the king stood, he would ceremonially cut the first sheaf of grain to symbolize his connection between the gods, the land, and the people and offer the grain to the god in sacrifice. The festival honored the king as well as the god in the hopes of a continued prosperous reign which would bring fertility to the land and the people. 28

Other Festivals

The Beautiful Feast of the Valley, held in honor of the god Amun, was staged in Thebes for the dead and celebrated with processions of the barks of the gods, as well as music and flowers. The feast of Hathor, celebrated in Dendereh, was a time of pleasure and intoxication, in keeping with the goddess’s cult. The feast of the goddess Isis and the ceremonies honoring Bastet at Bubastis were also times of revelry and intoxication. Another Theban celebration was held on the nineteenth of Paophi, the east of Opet, during the Ramessid Period (1307–1070 B.C.). The feast lasted 24 days and honored Amun and other deities of the territory. In the New Kingdom Period (1550–1070 B.C.), some 60 annual feasts were enjoyed in Thebes, some lasting weeks. The Feast of the Beautiful Meeting was held at Edfu at the New Moon in the third month of summer. Statues of the gods Horus and Hathor were placed in a temple shrine and stayed there until the full moon.

The festivals honoring Isis were also distinguished by elaborate decorations, including a temporary shrine built out of tamarisk and reeds, with floral bouquets and charms fashioned out of lilies. The Harris Papyrus also attests to the fact that the tens of thousands attending the Isis celebrations were given beer, wine, oils, fruits, meats, fowls, geese, and water-birds, as well as salt and vegetables.

These ceremonies served as manifestations of the divine in human existence, and as such they wove a pattern of life for the Egyptian people. The festivals associated with the river itself date back to primitive times and remained popular throughout the nation’s history. At the first cataract, there were many shrines constructed to show devotion to the great waterway. The people decorated such shrines with linens, fruits, flowers, and golden insignias. 29

The ancient Egyptians had submitted themselves to the will of the devil and had surrounded themselves with various manifestations of their many gods. Even with such developed minds, they could not decipher the fact that if a being was dependent, he could never be a God because a God is a Supreme Being who is Omnipotent, Omnipresent and is the Source of all good. Their religion was nothing more than a collection of few myths and rites which were concocted so that the priests and the elite could collaborate and do whatever they liked in the society and remain unanswerable for it. This resulted in the destruction of human social, moral, ethical, cultural and other important values of the society. Since this phenomenon existed in other major civilizations of the world as well, the whole world was in a chaos. To save humanity, God sent his pious prophets (some were specifically sent to Egypt as well) so that they could guide humanity towards the right path, but still, most people remained stubborn and not only refused to believe in their message for few short-lived worldly benefits.

- 1 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 160.

- 2 P. Le. Page Renouf (1884), Lectures on the Origin and the Growth of Ancient Egypt, Williams and Norgate, Edinburgh, U.K., Pg. 83.

- 3 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 154.

- 4 A. M. Blackman (1923), Luxor and Its Temples, A. C Black Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 161-162.

- 5 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/place/Karnak : Retrieved 14-06-2017

- 6 Emily Teeter (2011), Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge University Press, New York, USA, Pg. 16.

- 7 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version):https://www.britannica.com/topic/priesthood : Retrieved: 10-06-2017

- 8 Emily Teeter (2011), Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge University Press, New York, USA, Pg. 16-21.

- 9 Rosemary Clark (2000), The Sacred Tradition in Ancient Egypt: The Esoteric Wisdom Revealed, Llewellyn Publications, Minnesota, USA, Pg. 369.

- 10 Emily Teeter (2011), Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt, Cambridge University Press, New York, USA, Pg. 21-25.

- 11 Patricia Netzley (2003), The Green Haven Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Green Haven Press, Michigan, USA, Pg. 311.

- 12 Norman Bancroft Hunt (2009), Living in Ancient Egypt, Chelsea House, New York, USA, Pg. 79.

- 13 Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 307.

- 14 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 160-161.

- 15 Patricia Netzley (2003), The Green Haven Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Green Haven Press, Michigan, USA, Pg. 243-244.

- 16 Rosemary Clark (2003), The Sacred Magic of Ancient Egypt: The Spiritual Practice Restored Llewellyn Publications, Minnesota, USA, Pg. 144-145.

- 17 Don Nardo (2015), Life in Ancient Egypt, Reference Point Press, California, USA, Pg. 76-77.

- 18 Ian Shaw (2000), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, New York, USA, Pg. 68.

- 19 A mastaba is a kind of antiquated Egyptian tomb as a level roofed, rectangular structure with internal inclining sides, built out of mud-blocks (from the Nile River). These structures denoted the internment destinations of numerous prominent Egyptians amid Egypt's Early Dynastic Period and Old Kingdom. In the Old Kingdom age, nearby lords started to be buried in pyramids rather than in mastabas, in spite of the fact that non-imperial utilization of mastabas proceeded for over a thousand years. Egyptologists call these tombs mastaba, from the Arabic word مصطبة which means bench of stone.

- 20 Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 251-253.

- 21 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): http://www.ancient.eu/article/44/ : Retrieved: 13-06-2017

- 22 Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 253-255.

- 23 Charlotte Booth (2007), The Ancient Egyptians for Dummies, John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Sussex, U.K., Pg. 180.

- 24 Patricia Netzley (2003), The Green Haven Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Green Haven Press, Michigan, USA, Pg. 116-117.

- 25 Rosemary Clark (2003), The Sacred Magic of Ancient Egypt: The Spiritual Practice Restored, Llewellyn Publications, Minnesota, USA, Pg. 239-240.

- 26 Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 290-291.

- 27 Toby Wilkinson (2010), The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt, The Random House, New York, USA, Pg. 87.

- 28 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): http://www.ancient.eu/article/1032/ : Retrieved: 14-06-2017

- 29 Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 138.