Economic System of Ancient Greece – System & Structure

Published on: 20-Jun-2024(Reference: Dr. Imran Khan & Mufti. Shah Rafi Uddin Hamdani (2020), Encyclopedia of Muhammad ﷺ, Article: 07, Seerat Research Center Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 211-226.)

Due to the poor quality of Greece's soil, the Greek economy was largely dependent on the import of goods. However, the limited production of crops did not hinder the growth of Greece since it was located in a prime position amidst the Mediterranean Sea which gave its provinces the control over Egypt's most crucial sea ports and trade routes. The pivotal aspects of the Greek economic output were maritime activities, trade, craftsmanship and commerce.

Overall, Greece did not have a consolidated centralized economy. Economics was primarily understood in terms of the localized management of necessary goods, though scholars have revealed that the ancient Greek philosophers were concerned with questions that would today fall under the discipline of economic theory.

One of the most important facts about life is that human beings cannot get on without food, clothing, and shelter. Most modern men regard it as the most important fact of all, and spend most of the waking hours of a brief lifetime in trying to deal with it. Same was the case with Greeks. They were also interested to satisfy their lavish desires through different means. They gave their preoccupation with it a name, which has stuck to it ever since; they called it Housekeeping or Economics. 1

Useful evidence for economic activities of Greece survives from the fifth and fourth centuries B.C., the “classical” period, than from earlier or later periods of Greek history. The most valuable written sources are inscriptions, which proliferate as the two “classical” centuries unfolded to encompass far more than the limited pre-500 repertoire of laconic gravestones and one-line dedications. Laws and decrees of state, calendars of sacrifices (often stating the prices of victims), leases of public property, and records of property sold or pledged, and especially annual accounts of public financial transactions drawn up and promulgated by state or sanctuary officials, all yield invaluable insight into economic activities and systems.

Such written material was complemented in two ways by physical evidence. The first was the landscape itself. Right across the zones of Greek culture and settlement, such surveys have provided a basis for estimates of population, settlement pattern, and other activities at various periods from the Neolithic to the present day.

The second group of physical evidence comprises the tangible objects which were created and used. These range from installations such as houses, temples, public buildings, and infrastructure, through weaponry, ceramics, coins, textiles, and the normal furnishings and equipment of a dwelling house or a farm, to the more exotic and high-value products of the sculptor or the silversmith.

For wealthy Greeks, land ownership remained the main source of wealth. The distribution of land varied from region to region. Athens, for example, had a much larger number of landowners, and each owned a relatively smaller piece of land. In the lush farm country of Boeotia, most of the land remained in the possession of a small number of aristocratic families. 2

Money

Homer did not mention money in the modern sense, however, as a measure of value, the ox was employed. It must be understood that the ox was seldom used as a medium of exchange, but rather as a unit of reference to which prices could be indicated. If we were to conclude that the ox was the sole unit of value, our picture of a system of exchange based thereon would be a simple and quite recognizable one. But the problem is severely complicated by the existence of another unit, the talent, one of several ancient units of mass, a commercial weight, as well as corresponding unit of value equivalent to these masses of a precious metal. Evidently by the time of Homer the old and clumsy ox unit was beginning to be challenged, and the idea of using a more exact and convenient method in reckoning the weight in terms of a precious metal, gold was emerging.

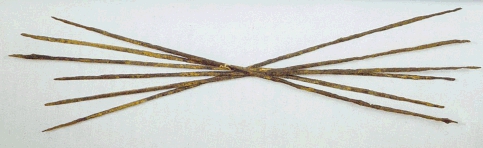

It must not be forgotten that iron at this period was so scarce and valuable that it ranked among the precious metals. Its use as money, therefore, except for the fact that it was rusted, was not at all extraordinary. Such iron money consisted of rods or spits, or obeloi, of which six could be held in the hand, from which, conjecturally yet not unreasonably, the Greeks adopted 6 obols to the drachma.3

By 600 B.C., trade was flourishing in and out of Greek ports, both on the mainland and abroad in the Greek colonies. About this time, the Greeks began using coins. (Previously, all trade was conducted using the barter system, where goods were exchanged for other goods of equal value.)Herodotus credits the wealthy Lydian kingdom in Anatolia, west of Ionia, with introducing coins as currency in the sixth century B.C. The Lydian coins were made of electrum, a combination of gold and silver, and they were stamped with an official seal to prove they were genuine. Even so, until the Persian Wars there was little money actually circulating in Greece.

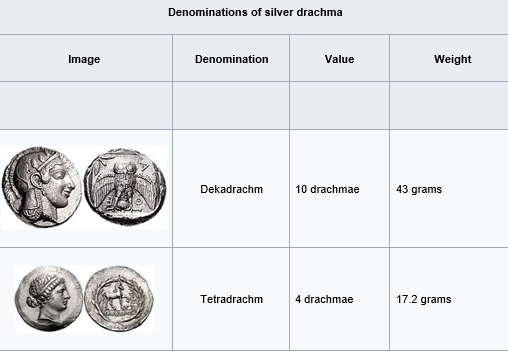

When silver was discovered at Laurium, Athenian silver coins became common. They were stamped with an owl on one side (a symbol of Athena) and the head of the goddess Athena on the other. The government symbols and heads of famous people found on today’s coins trace their roots to that practice.

One silver drachma was about what one skilled worker earned each day. Six thousand drachmas equaled one talent. An obol was one-sixth of a drachma, and bought enough bread for one day. One was equal to several copper coins. Each polis had its own coinage, and with all the money that began circulating in Greece, exchanging money and banking became common professions later in the fifth century B.C. It often was the work of metics or even educated slaves. 4

Monetary System of Sparta

Spartan money consisted of lumps of iron weighing to about 1.25 lb., which was hard to carry. Even small payments had to be transported in a cart drawn by a pair of oxen which was a sufficiently troublesome operation to discourage commercialism among the Spartan aristocracy. These unwieldy iron coins seem to have been equated in weight with the Aeginetan mina, each being worth of four chalkeis, or half an obol. Seneca talks of leather money used in Sparta, but this is unsubstantiated from any other source. But we do know that bartering was largely resorted to over there. 6

Over all, the Greek currency is described by Encyclopedia Britannica as:

“Drachma, silver coin of ancient Greece, dating fro=m about the mid-6th century B.C, and the former monetary unit of modern Greece. The drachma was one of the world’s earliest coins. Its name derives from the Greek verb meaning “to grasp,” and its original value was equivalent to that of a handful of arrows. The early drachma had different weights in different regions. From the 5th century B.C Athens gained commercial preeminence, and the Athenian drachma became the foremost currency. One drachma equaled 6 oboli; 100 drachmas equaled 1 mine; and 60 mine equaled 1 Attic talent.”7

As the Grecian cities were very different in character, the ideas which prevailed on this subject, could not be the same. In those states where agriculture was the chief employment. In maritime and commercial towns, of which the number was very considerable, the business of commerce must have been esteemed. But those who were employed in manufacturing and selling goods, were never able to gain that degree of respectability, which they enjoy among modern nations. 8

Agriculture

The varied landscape determined the location of agriculture. The climate was similar to that of today. The mountains of mainland Greece with prevailing western winds caused the highest rainfall to be in the west. Eastern Greece and the islands between Greece and Turkey were relatively arid, but the west coast of Turkey and nearby islands, such as Rhodes and Samos, were not as arid. Rainfall was often in the form of heavy downpours rather than steady light rain, making agriculture difficult, particularly cereal growing. Eighty percent of the country was mountainous, so agriculture was practiced in the plains and the small pockets of lower land between the mountains.

Colonies were generally established in areas with good agricultural land, especially for growing grain. Agriculture was a major industry and was carried out by the inhabitants of towns and cities, as well as people living in isolated farms and villages. Market gardening also appears to have been widespread. The staple food was grain, wine and olive oil—not meat, fish or dairy products. Communities usually practiced mixed agriculture, although occasionally there was an emphasis on particular crops or animals.

Crop Production

Grain was the most important crop, although the climate and terrain meant that yields were never very great. Crops were not cultivated on behalf of city states, but by individual farmers on their own land, and there were no public granaries. Wheat was often imported, but never barley. Wheat and barley were cultivated, and sowing was normally in the autumn, although some spring sowing took place for fast-ripening crops or as an emergency measure when the autumn sowing had not taken place or had failed. Millet was also grown, and from the Classical period oats and rye. A crop rotation leaving land fallow for a year between crops appears to have been practiced, especially in the drier areas, allowing some fallow land to preserve moisture. The fallow land was plowed several times in the months before sowing took place. Seed grain was sown by hand from a container such as a sack or basket, and the seed could be covered by hoeing. Between sowing and harvesting some hoeing and weeding took place. With the variations in land and climate, there must have been great variations in the yield of cereal crops. Another important crop from Mycenaean times was the vine. The grapes were mainly used for wine production, although some were eaten and some appeared to have been dried as raisins. Once a vineyard was established, grapes were a perennial crop. The vines were tended throughout the year with pruning in winter and spring. Vines were either freestanding or were supported by stakes or other trees. The ground between the vines was often planted with other crops such as barley or beans.

The third most important crop was olives. It is uncertain how olive trees were initially grown— probably by cuttings and or grafting. The olives were picked from autumn until early spring. Various other fruit and nut trees were cultivated. Apples, pears, plums, pomegranates, figs, almonds and quinces were grown in orchards, but there is little detailed evidence about their cultivation. Some fruits such as figs, apples and pears were sometimes dried to preserve them for storage. Nuts from wild hazel, walnut and chestnut trees also seem to have been harvested. A variety of other crops were grown, such as peas, beans, lentils, cabbage, onions, garlic, celery, cucumbers, lettuces, leeks, artichokes, carrots, pumpkins, beets and turnips, but it is unclear whether they were grown on a large scale or as market garden crops. Herbs appear to have been gathered mainly from the wild rather than cultivated in the garden. 9

Bee Keeping

Bee keeping was general at a time when sugar was not used and only known as an Asiatic rarity. It was so common in Attica that regulations were necessary as to the distance between the hives on the hillsides. Attic honey was famous, especially from Hymettus. 10

Animal Husbandry

Ancient authors do not provide a great deal of information about farm animals, and evidence from other sources is also sparse. Goats and sheep appear to have been common in many areas, providing milk, cheese and meat. Sheep also provided wool. Pigs were raised for their meat, and poultry to provide eggs. Horses were a luxury and a status symbol and were used only in battle, for racing and sometimes for transport. Oxen, donkeys and mules were bred as draft and transport animals. Cattle were mainly used for producing oxen and not for milk, since the Greeks preferred milk and milk products derived from sheep and goats. Because of the varying terrain, some areas were much more favorable to animal husbandry than others with larger animals more commonly reared in the less arid north and western parts of Greece. Sheep, goats and, to a lesser extent, pigs were found almost everywhere. Thessaly and the Peloponnese were particularly known for horses, oxen, sheep and goats, while Euboea and Boeotia were noted for oxen, and Arcadia for sheep and mules. Transhumance was practiced, with herds of cattle and sheep exploiting mountain pastures in summer and lowland pastures in winter, although keeping to the boundaries of the polis so as not to generate disputes between neighbors over rights to pasture. Sick animals were usually treated by the farmers, but there were veterinarians (hippiatrikoi) who could provide medical and surgical treatment to animals if required. 11

Taxation

Taxation remained the main source of revenue for the majority of Greek cities as it was one of the common practices of the ruling class to forcefully collect money from the public as of taxes and use it for their personal luxuries. This reveals the values, economic mentality and the lavishness of the ruling class in Greece. Direct and regular taxes on the property of citizens and especially their favored persons were rarely avoided. Tyrants resorted to them occasionally, but cities with republican-type constitutions abolished them as far as possible.

There was no hesitation in taxing non-citizens. Thus, metics in Athens had to pay regularly a special tax. But if regular taxes on citizens and their property were felt to be unacceptable, the city had all the same to make use of the wealth of its members. In Athens citizens (and also metics) were bound, according to their wealth, to undertake liturgies (literally, services for the community, such as the trierarchy, in which the state supplied triremes, while the trierarchs had to provide for their upkeep and commanding.

The government taxed economic activity in its various forms in different ways, without ever wondering whether it was thereby harming the interests of citizens or not. For instance, in 413 B.C. at the time of financial stringency caused by the Peloponnesian War, the Athenians thought of increasing their revenues by abolishing the annual tribute they exacted from their allies in the Delian League and replaced it by a 5 per cent tax on all the trade, transiting in the harbors of the Athenian empire; later on, between 390 and 387, they sought to re-impose this same tax on their former allies. This tax fell indiscriminately on the Athenians, their allies and everybody else, Greek or non-Greek, who traded in the Athenian sphere of influence. Generally speaking, it would appear that before the Hellenistic period taxes on economic activity only served a purely fiscal purpose of raising revenue which was used to support the ruling class instead of a lay man.

The exploitation of economic activity for fiscal purposes originated, in the archaic period. In the classical period Athens pursued these techniques with even greater success as the growth of Athenian power after the Persian Wars made Peiraieus not only the most important military port in the eastern Mediterranean, but also its greatest economic center. The power and prosperity of Athens attracted traders from almost everywhere in search of a market where everything might be bought and sold. Athenian sources of the classical period never fail to emphasize the variety and abundance of all the foreign goods that were to be found in Athens. Even after the disaster in the Peloponnesian War; Peiraieus did not lose its role as a great economic center; it was partly this which helped Athens to get over the worst moments of the financial crisis after the Peloponnesian War. The main tax at Peiraieus was the tax of one-fiftieth (2 per cent) raised on all goods, both exports and imports, and whatever their country of origin. Other taxes were raised on goods sold in the agora in Athens, on foreigners who traded there, on sales by the city of goods which belonged to it (through confiscation, for example), through fines in the law courts, etc. 12

Taxes normally are imposed to provide better facilities for the citizens, and to provide for the poor and needy of a country along with all the security and other important needs. Still, this taxation system needs to ensure that it is not being a burden on the poor and even the middle class. This type of taxation was not found in any of the ancient civilizations including the Greeks. Even here, a particular class was abused while the elite enjoyed the benefits.

Government Budget

Ancient Greek finance was indeed parochial, almost childish, in its methods. The first and most obvious duty of the financial administration in a modern state was to get the Budget voted. The Budget, of course, had nothing to do with money received or spent in the past. It made provision for the year to come, and involved an estimate of the total revenue and expenditure to be expected from all sources. Greek Parliaments never had a Budget presented to them at all. They simply voted sums of money whenever occasion arose, stating in each case where the money was to come from. The State receipts might be lying in two or three or half a dozen different treasuries, looked after by different committees, these treasuries being, in the case of Delos, where the inscriptions enable us to study the financial administration in detail, simply so many jars bearing on each of them a label stating where its money came from and for what purpose it was ear-marked. In this way things jogged on from year to year, and no attempt was made for there was no one expert and continuous authority to make it to forecast possible expenditure ahead. The usual practice was to make both ends meet for the year and then to distribute the surplus among the citizens.13

Banking

If we are content to use the word ‘banking’ in a loose sense of the storage of valuables and the lending of money at interest to borrowers without any technique commonly associated with modern banking practice, it is safe to say that a primitive form of bank was found in the temples of Babylonia as early as the time of Sumer. Although in ancient times, the temples were repository of valuables, and it is interesting to know that in the troublesome times, these hermitages were used as back up reserves.

With the extension of commerce and the evolution of money economy under the Persians in the ‘Neo Babylonian’ period after 600 B.C, there grew up a much more advanced form of banking practice in private hands. We know of at least famous banking houses in Babylon, the Egibi Sons and the Murassu, who evidently carried on a very large and, even according to modern standards, complicated business. Loans were made on a large scale both to governments and private individuals. Orders were accepted to pay from the amount of one merchant to another, and the partners acted as commission men to buy on behalf of a client. They received deposits and paid interest thereon; acted as warehousemen and charged a fee for safekeeping. They lent money on mortgage and went in to partnership with traders, making the necessary advances of capital, in such cases the borrowers taking the risks and the bankers dividing the profits with them.

With the rise of commerce and a money economy in Greece, the same evolution in the practice of banking as had been seen in Babylonia followed there. The temples were the earliest treasuries, from which loans were made to states, and apparently, but the evidence is not perfectly plain, to individuals. The temple of Delos, when under Athenian control, lent sums for five years at 10 percent, and temple of Athena at Athens lent money to state between 433-427 B.C. at 6 percent. 14

Banking in Athens

The business of banking in Athens, like nearly all commercial pursuits, was largely in the hands of metics. Pasion, the most famous and wealthy of all Greek bankers, was originally a slave. His masters were Antisthenes and Archestratus who were bankers themselves.

Although there were rich and famous bankers, yet the business of money lending and foreign exchange was, in large measure carried on by a swarm of individuals, who were notorious for their sharp practices and extortionate rates of interest. They were also called ‘money sharks’ of the worst description. So lowly and despised was this trade that Xenophon considers it one of the last refuges of the ruined farmer. When agriculture became unprofitable, many farmers, quit their occupation of tilling the soil, and opted for other businesses such as inners, and money lenders etc. because it was very easy for them to earn money via interest without working.

The bank of Athens also acted as intermediaries in payments between individuals. Demosthenes view of this practice was:

“It is the custom of all bankers when any private individual deposits a sum of money with directions to pay it to any particular person, first to write the name of the party depositing and the sum, then enter in the margin that it is to be paid to this or that person, and if they know the face of the person to whom they are to pay, they do only that; but if they do not know him, they add the name of him who is to introduce the person who is to receive the money.”15

Shipping Loans

Undoubtedly, of all banking and loan business, the most general and at the same time, the most lucrative and hazardous were the loans made to the merchants and shipmasters for the furtherance of commercial ventures overseas trade. Such transactions have been generally described by the modern term of bottomry loans, 16 but this is not strictly correct.

As for the existence of a state bank, there are some accounts which give some information about it, but are unclear, hence due to lack of evidence we are not sure about the presence of a state bank in ancient Greece. 17

Industries

During the Middle Ages, mankind reverted to the primitive custom of making everything at home which was needed in house or the field. The village smith and potter wrought for their immediate neighborhood. In the coastal towns were shipwrights skilled in building the small, round-bottomed boats of the time propelled by a sail and at most by thirty oars. With the help of his slaves the lord built his own house, and women wove the necessary garments. Only the rich could purchase a few luxuries, as tapestries, jewelry, and medicine from Ionian or Phoenician traders, or beautifully dyed wool and linens brought from Lydia and Caria. Gradually, however, as life became more settled, and wealth accumulated in the hands of lords, there arose a demand for better wares which were supplied by skillful people. Those who had skill and thrift grew wealthy. Majority of the lords and nobles invested in this part of trade since it was so profitable, and men of the same industry formed one group for mutual encouragement and protection.

Industries of Lydia, Ionia and Lesbos

The industries of the new age had their principal origin in Ionia and her neighbor Lydia, a country of diverse natural resources. Hence, it was that in the seventh century, Lydian headbands, sandals, and golden ornaments for the person were among the most highly-prized luxuries of Hellas. Soon, however, these products were excelled by the brilliant efforts of Ionians and Lesbians. Miletus won fame for her finely woven woolens of rich violet, saffron, purple, and scarlet colors, and her rare embroideries for the decoration of hats and robes. Notably Glaucus of Chios discovered a process for welding iron, which proved invaluable in the useful and fine arts. About the same time certain Samians introduced bronze casting into Greece from the Orient.

Aegina and Chalcis

Naturally the extension of skilled industry over Greece was from East to West. Aegina, whose scant soil forced the people to industry and commerce, produced bronze work— such as cauldrons, tripods, and sculptured figures and groups — in addition to small wares of various kinds. In Euboea, on the strait of uripus, Chalcis became a thriving industrial city. With bronze, obtained in part from neighboring mines, and with the purple mollusk caught in the strait, the city manufactured wares for war and peace and costly dyes for kings and nobles. 18

Why did the Greeks Indulge in Trade?

Athens engaged in active foreign trade throughout the classical period. Much of the trade took place on the Aegean Sea. Trade over land routes existed but at a much lower rate. There are several reasons for Athenian foreign trade to be so prosperous:

1. A shortage of domestic grain production necessitated trade.

2. The wide circulation of Athenian silver coins over the Greek world and adjacent countries facilitated trade.

3. The dominance of the Athenian navy over the Aegean Sea made the voyages of Athenian merchants safer.

4. Peiraieus provided excellent port facilities.

5. In Athens and Peiraieus there were bankers who extended maritime loans and money-changers dealing with foreign currency exchange and testing.

6. There was an efficient legal system dealing with trade disputes.

7. In Athens and Peiraieus there was the office of proxenos, much like the modern consul, who looked after the needs of foreign merchants. 19

Trade

The Greeks (along with their neighbors, the Phoenicians) were the greatest traders and seafarers of the ancient Mediterranean world. They sailed far and wide, constantly searching for new commercial markets and trade opportunities. It is known that as early as about 1300 B.C., long before the invention of coinage, Mycenaean-Greek merchants were spanning the Mediterranean and trading by barter. Archaeologists have discovered that these early Greeks had trade depots in the Lipari Islands (near Sicily) as well as on Cyprus, in western Asia Minor, and in the northern Levant.

During the Greek’s trading and colonizing expansion around 800–500 B.C., Greek merchants visited southern France and Spain and the farthest corners of the black sea. In about 308 B.C., a Greek skipper named Pytheas of Massalia explored the Atlantic seaboard, sailing around Britain and perhaps reaching Norway in his search for new trade routes.

In many cases, Greek traders were inspired to travel these amazing distances by the need to acquire certain valuable resources unavailable in Greece. Southern Spain, for example, offered raw tin, a necessary component of the alloy bronze, a metal essential to many aspects of ancient Greek society for centuries. In the elaborate trade network of the ancient Mediterranean, tin was quarried by Celtic peoples in British Cornwall and (possibly) in northwest Spain, and it was brought to the Greek market, overland to the Mediterranean, by Celtic middlemen. Other prized resources of the western Mediterranean included silver ore and lead. In exchange, the Greeks offered metalwork, textiles, and wine, brought from mainland Greece or from the Greek cities of Asia Minor. 20

Policy

It is widely accepted that Athens at the height of its power in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. had to regularly import very substantial quantities of grain to provide for the population of Attica. In this respect Athens differed from all other Greek poleis, and this abnormal dependency upon foreign production was held to explain aspects of Athenian actions abroad—indeed to build up a notion of an Athenian foreign policy. 21

Greek cities had an import policy which aimed at ensuring the supplying of the city and the citizens with a number of goods essential for their livelihood, but not an export policy aimed at disposing on favorable terms or even imposing abroad 'national' produce in competition with rival cities. If a Greek city took into account the economic interests of its members, it was solely as consumers and not as producers. One cannot therefore talk of any 'commercial policy' on the part of Greek cities except in a deliberately very restricted sense: what they practiced was solely an import not an export policy. 22

Grain Trade in Ancient Greece

Among the different import trades, the grain trade occupies a very special position. The beginnings of the import of corn towards the Greek world from Egypt, the Black Sea and Sicily in the archaic age, were seen earlier. In the classical period, this trade developed on a substantial scale in many Greek cities, and especially in Athens where the considerable growth of the city in the fifth century increased Athens' dependence on imports of foreign corn.

The grain trade is the only trade which the Athenian law sought to regulate in this manner. It is clear that the only concern of the city here was to ensure the regularity of imports and protect the interests of the citizen-consumers. It is particularly noteworthy that the city never apparently worried about the citizens who were corn producers themselves in Attica and the possible effects on them of large-scale imports of foreign corn.

The other commodities which Athens sought to control, directly or indirectly, were the sources of supply that one may refer to as strategic materials. Under that heading one can include anything which might be of importance in the manufacture of weapons, and especially in the constructing and equipping of the war fleets on which the power of Athens rested. It is one of the paradoxes of the history of Athens that, although it was primarily a naval power, it did not have in Attica adequate resources for the navy. These included, in particular, construction timber, but also metals, linen for sails, pitch and vermilion for the painting of the hulls. The means used by Athens to secure these commodities varied at different times. Sometimes Athens simply relied on their military and political supremacy, at other times it had to resort to diplomacy.

Timber Trade

By the classical period central and southern Greek poleis were not blessed with supplies of wood sufficient for their needs, so they were forced to seek it elsewhere. Classical Athens imported wood for temple fittings, housing, furniture, and fuel, but we are more interested in the wooden walls vital for her military prowess. Timber had to be imported long-distance in merchant ships to classical Athens, where the warships were built. The major Athenian source of such wood was Macedonia, where timber was a royal monopoly. 23

Mining System

The Greek cities which had important mines on their territory or in their sphere of control was a source of revenue which could not be allowed to remain in the form of private property. These mines were the essential sources of metal, both precious and common, and were of great importance to them. The general tendency for Greek cities was therefore to monopolize the ownership of mines in order to ensure their revenues. There is little information on the exact modes of exploitation of the mines, which must have varied according to time and place. The best-known case is that of the Laurion mines in Attica from which Athens derived the largest part of the silver, which it used for striking their abundant silver coinage in the classical period and which was one of the key elements in their prosperity. Little is known of the exploitation of these mines in the fifth century.

The city kept for itself the ownership of the mines, but instead of exploiting them directly for their own benefit, leased them out to individuals (who were all apparently citizens) for specific time in return for payments which varied according to the type of mine that was being worked (the details are often uncertain). Although some leaseholders worked their mines themselves, slave labor was generally resorted to. In periods of most intensive working, there may have been thousands of slaves active at Laurion, among them many slaves of Thracian and Paphlagonian origin who came from mining regions. The leaseholders were more or less always Athenian citizens. Among the known names one can find many men who played an important role in the political and social life of Athens in the fourth century. If lucky, a leaseholder might make a fortune; but there was always an element of risk in these enterprises of this kind, and the exploitation of the mines varied in intensity according to political and economic conditions.

Control of Economic Activity

The raising of various indirect taxes was generally carried out by private contractors. The farming of the taxes was auctioned by the city, but there also existed a number of magistracies which dealt with economic activity in general, as for example in Athens in the fourth century the inspectors of the market (agoranomoi), the inspectors of measures (metronomoi), the commissioners of the corn trade (sitophylakes) and the inspectors of the commercial harbour (epimeletai emporiou). These magistracies performed different functions. Some supervised the corn supply, as seen above (the sitophylakes and the epimeletai emporiou), others dealt with the policing of markets more generally; no specifically economic preoccupation was involved here, but only a concern to supervise and keep law and order. It is probably to this same concern for law and order that one must attribute the practice, widely attested from Thucydides onwards, of establishing special temporary markets outside cities when foreign armies happened to be passing by and asked to be allowed to supply themselves. Occasionally in some oligarchic states the wish to supervise economic activity was prompted by deeper motives and it was economic activity as such that was to be kept under control. In Thessaly, for example, the different functions of the agora (which was originally a meeting place for the community before it became an economic center) were deliberately separated. There was a 'free' agora which was reserved for civic and political activity, and from which all economic functions were deliberately excluded. The latter were concentrated in a special agora, the commercial one. These same principles are found again in the philosophers: Aristotle adopted for his own purposes the distinction between the 'free' and the commercial agora, and Plato in the Laws laid down that foreign traders should be received only outside the city and that one should have only the minimum of relations with them. Here one meets once more old prejudices, directed partly against economic activity as such and partly against the outside world and all the risks of harmful foreign influences that it involved. 24

Greek Market Place

The word Agora (pronounced 'Ah-go-RAH’) was Greek for 'open place of assembly’ and, early in the history of Greece, designated the area in the city where free-born citizens could gather to hear civic announcements, muster for military campaigns, or discuss politics. Later, the Agora defined the open-air, often a tented, marketplace in a city (as it still does in Greek) where merchants had their shops and craftsmen made and sold their wares. The original Agora of Athens was located below the Acropolis near the building which today, is known as the Thesion and open-air markets are still held in that same location in the modern day.

Retail traders (known as kapeloi) served as middlemen between the craftsmen and the consumer but were largely mistrusted in ancient times as unnecessary parasites. These retail traders were mostly metics, while the craftsmen could be metics, citizens or even freed slaves who had become skilled artisans.

In the Agora of Athens there were confectioners who made pastries and sweets, slave-traders, fishmongers, vintners, cloth merchants, shoemakers, dressmakers, and jewelry purveyors. A special separate 'potters’ market' was reserved for the buying and selling of cookware as that was considered solely the provenance of women and was frequented by female slaves on task for their mistresses or by the poorer wives and daughters of Athens. 25

The economic system of ancient Greece was more developed than the other civilizations of the world, but due to its un-just and forced taxation, banking systems, this system was more beneficial for the elite, and was a nuisance for the common people. It was due to this system that the ruling class kept exploiting of the poor and hardworking people and forced them into acquiring debts which eventually pushed them into debt-based slavery. On the contrary historical records state that the economic system implemented by Prophet Muhammad  created a state in which interest based monetary systems were abolished, poverty was eradicated and all the unnecessary taxes were also abolished. Due to such brilliant economic policies, the city of ancient Madinah became one of the power centers of the world.

created a state in which interest based monetary systems were abolished, poverty was eradicated and all the unnecessary taxes were also abolished. Due to such brilliant economic policies, the city of ancient Madinah became one of the power centers of the world.

- 1 Alfred E. Zimmern, (1911), The Greek Common Wealth, the Clarendon Press, Oxford, U.K., Pg. 207.

- 2 Walter Scheidel, Ian Morris & Richard Saller (2008), The Cambridge Economic History of the Greco-Roman World, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K, Pg. 333-335.

- 3 H. Michell (1940), The Economics of Ancient Greece, Cambridge at the University Press, London, U.K., Pg. 314-316.

- 4 Jean Kinney Williams, (2009), Empire of Ancient Greece, Chelsea House Publishers, New York, USA, Pg.81

- 5 Wikipedia the Free Encyclopedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Greek_coinage : Retrieved: 01-20-2018

- 6 H. Michell (1940), The Economics of Ancient Greece, Cambridge at the University Press, London, U.K., Pg. 321-322

- 7 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online version): https://www.britannica.com/topic/drachma: Retrieved: 19-05-2017

- 8 Arnold H. L. Heeran (1824), Reflections on the Politics of Ancient Greece (Translated by George Bancroft), Cummings, Hilliard & Co., Boston, USA, Pg. 189-190.

- 9 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 186 -187.

- 10 H. Michell (1940), The Economics of Ancient Greece, Cambridge at the University Press, London, U.K., Pg. 73.

- 11 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 188 -189.

- 12 M. M. Austin & P. Vidal Naquet (1977), Economic and Social History of Ancient Greece, Batsford Academic and Educational Ltd., USA, Pg. 121-123

- 13 Alfred E. Zimmern (1911), The Greek Common Wealth, Oxford at the Clarendon Press, Oxford, U.K., Pg. 211

- 14 H. Michell (1940), The Economics of Ancient Greece, Cambridge at the University Press, London, U.K., Pg. 333-335.

- 15 Ibid, Pg. 335-351.

- 16 At the point when the proprietor of a ship borrows money and uses the ship itself (alluding to the ship's base or bottom) as collateral. In case of disaster that the ship is lost over the span of the voyage then the bank will lose on the credit; if the ship survives, the lender will get the principal in addition to premium.

- 17 H. Michell (1940), The Economics of Ancient Greece, Cambridge at the University Press, London, U.K., Pg. 335-351.

- 18 George Willis Botford (1926), Hellenic History, The Macmillan Company, New York, USA, Pg. 55-58.

- 19 Takeshi Amemiya (2007), Economy and Economics of Ancient Greece, Routledge, New York, USA, Pg. 80.

- 20 David Sacks (2005), Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World (Revised by Lisa R. Brody), Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 353.

- 21 Helen Perkins & Christopher Smith (1998), Trade, Traders and the Ancient City, Routledge, London, U.K., Pg. 99.

- 22 M. M. Austin & P. Vidal Naquet (1977), Economic and Social History of Ancient Greece, Batsford Academic and Educational Ltd., USA, Pg. 113.

- 23 C. M. Reed (2003), Maritime Traders in the Ancient World, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., Pg. 19-20.

- 24 M. M. Austin & P. Vidal Naquet, (1977), Economic and Social History of Ancient Greece, Batsford Academic and Educational Ltd., USA, Pg. 120-121, 123-124.

- 25 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version) http://www.ancient.eu/agora/ : Retrieved: 04-06-2017