Religious Beliefs of Greece – Polytheism & Mythology

Published on: 13-Jun-2024(Cite: Khan, Dr. (Mufti) Imran & Hamdani, Mufti Shah Rafi Uddin. (2020), Religious Beliefs of Ancient Greece, Encyclopedia of Muhammad  , Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 115-134.)

, Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 115-134.)

Every human on this earth has some beliefs, but his belief may exist in a peculiar form, and vary from person to person. However, the people who had Prophets amongst them, had a better chance of being close to the divine religion. By choice, no society opted for secularism, or enmity towards religion, because the word ‘Deen’ in its simplicity means ‘a path or way of life’, and its viable definition is stated as ‘a guideline to live a life’ or ‘a law for spending a lifetime’. Likewise, the Greeks, as portrayed by historical evidence, had a set of beliefs which were not divinely revealed, but were self-forged and based on polytheism.

Greeks had no word for Deen. Gods were thought to be everywhere, and religion was part of everyday life i.e. it was not divorced from mundane activities, and therefore no word categorized it. It was believed that the gods could see all human activities, provide for all human needs, protect against danger and heal the sick. In return, they were worshipped according to their functions and spheres of influence. People offered sacrifices, votive offerings and prayers, and looked after the gods’ sacred places. Except for a few specific cults, the Greeks did not expect the gods to provide salvation after death (as in the Christian sense), but rather rewards and favors during life in return for piety, service and sacrifice to the gods. The limitation of the beliefs to this physical world was an allusion to the limitations of their minds. This limited mindset and continuous urges for worldly pleasures led these people to develop a concept of god and religion which was faulty in nature.

Religious observance accompanied all important private and public events and transactions. During the classical period no significant private or public undertaking was started without consulting a god, and no successful outcome went without a votive offering, vow of thanks or public dedication. In Athens religious observance was usually further organized within membership of groups, such as a deme, professional organization, phratry or family. 1

The theology of Greeks contained ideas of cosmos and idol worship, and their list of idols, like the Aryans and the Hindus, was lengthy. They had Gods and Goddesses, whose statues were fitted in huge temples, and rituals were performed in front of them. Like humans, their gods had weaknesses, but they were immortal.

In reality, Greek’s religion was never complete – unlike Islam which is a complete religion. Greek religion was incomplete because it was manmade, and the manmade sources of knowledge are incomplete and contradictory, therefore can never be made a source of knowledge. It kept on evolving with time. In their perspective, like earth, the heavens were also occupied by creatures. In appearance, the gods resembled humans, but the only difference was that they were more powerful, and were immortal. 2 The Greeks considered the gods as representatives of natural phenomenon. They were believed to be in human form and, to keep them happy, the people had to worship them and perform sacrificial activities. 3

Xenophanes was the first Greek figure that we know of to provide a set of theological assertions and he is perhaps best remembered for his critique of Greek popular religion, specifically the tendency to anthropomorphize deities. In a set of passages, which are probably the most commonly cited of Xenophanes’ fragments, we find a series of argumentatively styled passages against the human propensity to create gods in our own image:

But mortals suppose that gods are born,

Wear their own clothes and have a voice and body.

Ethiopians say that their gods are snub-nosed and black;

Thracians that theirs are blue-eyed and red-haired.

But if horses or oxen or lions had hands

or could draw with their hands and accomplish such works as men,

horses would draw the figures of the gods as similar to horses, and the oxen as similar to oxen,

and they would make the bodies

of the sort which each of them had.4

The ancient Greeks believed that their gods had a guiding hand in human affairs. Events as diverse as the annual sprouting of crops, disease epidemics, victory or defeat in war, and individual victories in sports events—which modern observers might assign to scientific causes—were seen by the Greeks as proof of the gods’ involvement in human events great and small. 5 One does not have to be a scholar to realize that life, as we know it, is a coherent system. If there was more than one god, each one would try to impose his working supremacy, and his system in place. This would have led to total chaos and the world would have been destroyed. This leads us to believe that there is only one Supreme Being who created this world under certain regulations. All the messengers of Allah also gave the same message of monotheism in their teachings as it is clear by the divine teachings of Quran.

Concept of God

Aristotle viewed god as:

“God is always in that good state in which we sometimes are, this compels our wonder; and if in a better this compels it yet more. And God is in a better state. And life also belongs to God; for the actuality of thought is life, and God is that actuality; and God's self-dependent actuality is life most good and eternal. We say therefore that God is a living being, eternal, most good, so that life and duration continuous and eternal belong to God; for this is God.” 6

Whereas Plato said:

That the earliest inhabitants of Greece, like many of the barbarians, had their gods the sun, moon, earth, the stars and heaven, and that these were called gods because they were always ‘running about’. 7

Furthermore, he said that there is a god who is good and who, by virtue of his goodness, is incapable of wishing for anything other than what is good or doing anything other than what is good. We can only aspire to free ourselves as much as possible from any distractions offered by our physical senses of sight and hearing, etc., and by our appetites for food and all other physical pleasure. In that way, we can become like god as far as that is possible for man. And this, indeed, is the aim in life, assimilation and approximation to god; this is not ‘‘becoming god’’, but it is for the soul to become like god as far as that is possible 8 since the only way for the body to emulate immortality is through physical procreation, as in that way part of oneself lives on (Symposium). The god thus emulated by one’s soul in fitting manner is the one characterized as all good and all-knowing. This entails that he cares for everything, and by implication everybody, and that he cannot be swayed by deception or flattery in the form of lies or prayers or sacrifices. 9

Hence, the matter of Greek religion was complicated. Their religion was not created by any Rishis (A Hindu Sage or Saint) or any other pious personality, but by poets, actors and philosophers. All these thinkers had no limitations to their thoughts and no sacred book was available to them, therefore their religion was basically a fragment of their imagination. Whatever they thought to be right, they made it the part of the religion and whatever they felt wrong, they rejected it. Since they were misguided themselves, they also led other people astray, made them believe in false beliefs, profligacy, and were responsible for their moral and social destruction.

Even though the Greeks didn’t have access to any basic religion, holy text or religious theories, they had a sense of the existence of a creator. The wish to see the gods in physical state urged the Greeks to create a statue of Zeus. It was crafted by Phidias, a great Greek sculptor (490-416 B.C.). This sculpture was praised, and respected by the Greeks. According to them, the statue of Zeus at Olympia represented the pinnacle of classical sculptural design. As per the sculptor, he thought that if any one looked at this masterpiece, he would delve deep and remain lost in the contemplation of god. By creating these statues, the Greeks sought to get a better concept of god, so that they may be more religious. 10

Regarding Greek Religion, Professor Adolf Holm states:

“During the centuries succeeding the settlement of the Greeks upon the soil of Greece, and preceding the Dorian invasion, their material civilization had made marked progress. They had in that interval become acquainted with the productions of Asiatic and Egyptian art, and had themselves made some advance in this direction. But such progress presupposes a development in general culture. By whatever route the earliest Greeks may have reached Europe, they remained in uninterrupted intercourse with their kindred in Asia Minor, and never ceased to receive from them impulses tending to the extension of their intellectual horizon. Their intercourse with the Phoenicians, who landed on the coast, must have had the same effect. The life of the Greeks gradually became fuller and more varied. But it was in religion more than in anything else that this constant intercourse with foreigners produced changes. And here one particular point is worthy of notice. There is perhaps no people whose religion is so difficult to reduce to a system as the Greeks, and none whose religion contains so many contradictory elements. The reason for this lies in the fact that among the Greeks there was never one class of men who were recognized as having the right to lay down the law in religion to the rest of the people. Religion was simply the expression of the popular mind, without exaggeration and without obscurity. Each race had perfect freedom to worship those gods which suited it, and each in the beginning had specially worshipped certain gods. The Greek religion, like every primitive one, is a nature religion. The same phenomena are manifested in all countries to mankind in their beauty, their beneficence, or their awfulness, and when personified become objects of worship. Behind the elements and their various manifestations, different deities were supposed to exist.” 11

In ancient times, Greece never existed as a united country, instead it was comprised of different city states. These city states had their own legal, political, and religious systems. Hence, the religious systems of each city state differed from the other. Some city states had fewer gods, whereas some states had many. Let’s take a succinct view of the different religious systems of ancient Greece.

Minoan Religion

In mainland Greece, evidence for religion is uncommon before the Late Helladic, but evidence exists, mainly on Crete, for religion in the Minoan period. The archaeological evidence was once interpreted as representing a unified religion based on the worship of one or more mother goddesses, and finds of female figurines were interpreted as images of deities. A reassessment of religion in early Crete has led to a picture of greater diversity in religious practice (and probably belief). Some religious practices were possibly more like those in the Near East than in later Greek religion. In particular it seems that individual communities tended to recognize different, very local gods and were not part of a unified and a fairly uniform religion. Priests and priestesses are represented, and rituals appear to have included processions and dances, offerings, sacrifices and practices apparently designed to cause the immediate appearance of a deity. Religious practices were conducted in outdoor settings, where a tree or rock was apparently of central importance in the ritual, but rituals also took place in caves and buildings. Religious sanctuaries on or near mountain peaks were possibly important communal religious centers, but other sites show the diversity of religious practice. One common religious practice was the offering of clay artifacts: Human figurines are often in poses of worship or invocation, while animal figurines and models of food on plates represented sacrifices.

Mycenaean Religion

It is unclear how the Mycenaean religion developed, but some continuity from Minoan religion is evident. Earlier evidence is sparse, but by the later Mycenaean period a distinctive religion had developed. Mycenaean religion was polytheistic, and the names of some gods are known: Zeus, Poseidon, Enyalios, Paean, Eileithyia, Hera, Dionysus and Hermaias (Hermes). There were also numerous goddesses, many of whom had the title potnia (lady). A goddess whose name translates as ‘Lady of Athana’ may be the same as the goddess Athena.

The evidence for worship of gods in Mycenaean times suggests some similarity to the forms of worship practiced later in the Classical period; offerings were made to the gods, and similar commodities and animals were sacrificed. Religion of the Classical period is generally regarded as having roots in Minoan and Mycenaean religion, but it is apparent that great changes in ritual (and perhaps belief) took place during the intervening Dark Age.

Dark Age Religion

Even in the Dark Age there was some religious continuity, although evidence for the continued use of a sacred site from Mycenaean times through the Dark Age and into the classical period is extremely rare. The open-air altar and temple with cult image were features of classical religion that appear to have arisen during the Dark Age. Some authorities do regard classical religion as a development from Minoan and Mycenaean religion, with influences from the Near East, but there is insufficient evidence to trace its development through the Dark Age. 12

Classical Religion

During the 6th century B.C. the rationalist thinking of Ionian philosophers had offered a serious challenge to traditional religion. 13 Greek religion as a progression, toward humane behavior and rationality, both ultimately doomed to succumb to foreign influences. 14

In the Classical period there were numerous deities, and every locality, river or spring had its own god or nymph. Gods were anthropomorphic, regarded as essentially like humans in their motives and behavior, but differing from humans in their superior power and their immortality. A complicated mythology developed around the gods, and many myths and legends were concerned with relationships between gods and other gods, and between gods and mortals. The Greeks tried to rationalize some of the myths, and some myths were adjusted or invented in order to create genealogies for particular people, because of the prestige in being descended from a god. This often resulted in differing versions of particular myths, or conflict between two or more myths.

There were religious festivals in honor of the gods, sometimes accompanied by sporting and artistic contests. As city-states expanded and admitted foreigners, foreign gods became established and accepted, often being equated with existing Greek gods. Since religion formed a major part of everyday activities, it provided virtually a common factor among all Greeks.

Hellenistic Religion

After the Classical period religion lost some of its popularity among the educated classes, although it still thrived among peasants. Religion was partly supplanted by philosophy, and after Alexander the Great, the Eastern practice of ruler worship became increasingly common. Alexander demanded and received divine honors from the Greeks, but his successors and their descendants seem to have been granted divine honors voluntarily. Kings and sometimes their families were worshipped as gods by the cities they had founded, and other cities usually enrolled a king among their official deities. They were worshipped with temples, cult statues and festivals. In time the monarchies of the East developed their own official cults, such as that of the Ptolemies at Alexandria. Ruler worship was usually political rather than truly religious; examples of offerings dedicated to rulers are known, but not prayers. It was generally regarded as an expression of loyalty to the state. 15

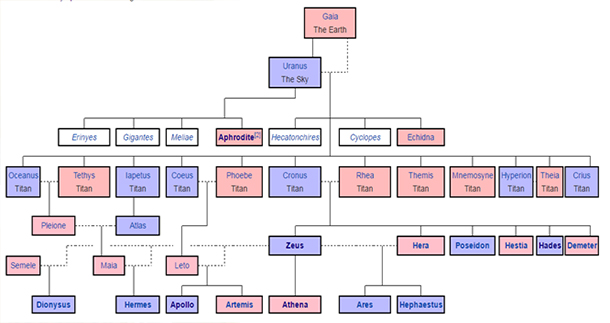

The Deities

Greeks believed that all of the gods were descendants of Uranos and Gé (Heaven and Earth). The first generation of gods, the immediate offspring of Uranos and Gé, were eighteen in number— three Hekatoncheires, three Cyclops, and twelve Titans, six of each sex. The names of the six male Titans were Oceanus, Kmos, Hyperion, Krios, Iapetos, and Kronos; and they, together with their sisters and associates the Titanides, were the progenitors of the dynasty of gods who were supposed to govern the world. Uranos, alarmed at the great strength and increasing power of his children, hurled the Hekatoncheircs and the Cyclops into the gloomy depths of Tartaros, and confined the Titans and the Titanides in the caverns of the earth; whereat their mother Ge became enraged, and found means of furnishing Kronos, the youngest and boldest of the Titans, with an iron scythe, with which he inflicted a severe wound on his father Uranos, and made himself and his brother Titans rulers of the universe. But the Cyclops and the Hekatoncheires still remained in Tartaros. Each one of the Titans begot many children, but those of Kronos, by his wife the Titaness Rhea, were the most powerful, especially Pluto, Poseidon, Zeus, Hestia, Demeter, and Hera. Kronos, fearing lest he should suffer from his children the same wrong which he had inflicted upon his own father, swallowed them as soon as they were born. But on the birth of Zeus, the youngest, Rhea, desirous of saving the child, deceived Kronos by causing him to swallow a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes. Zeus, having grown up, craftily induced Kronos to disgorge the other children. Afterward he made an attempt, with the assistance of his brothers, to snatch the kingdom of the world from Kronos and the Titans. A long and frightful combat ensued, in which all the gods and goddesses took part. Zeus released the Hekatoncheires and the Cyclops from Tartaros, and summoned them to his assistance. The former aided him by their surpassing strength and the latter by their invention of thunder. The war lasted ten years. The din of battle resounded throughout the broad earth, and was echoed across the bosom of the sea. Even the lofty sky trembled, and the mountains were shaken to their foundation. Finally, Zeus triumphed, and the conquered Titans were hurled into Tartataros, with the exception of Oceanus, who had taken the side of the victors. Thenceforward the scepter of the world remained in the hands of Zeus, who began to be called ‘the father of gods and men,’ while his brethren and their numerous progeny occupied important but subordinate positions in the hierarchy of the universe. 16 This signifies how confusing and perplexed were their beliefs regarding God’s authority and God-ship.

The Pantheon

A pantheon (‘‘all-gods’’) was the set of gods that Greek culture possessed, and because they were personal gods, they would tend to form a family. In modern treatments these tend to be formalized as the twelve Olympian gods. 17 As per the Greek beliefs, their twelve major deities are as follows: 1819

Zeus

In the words of George Grote:

“Zeus, who supplants his less capable predecessors, and acquires presidency and supremacy over gods and men – subject however to certain social restraints from the chief gods and goddesses around him, as well as to the custom of occasionally convoking and consulting the divine agora. In the order of legendary chronology, Zeus comes after Kronos and Uranos; but in the order of Grecian conception, Zeus is the prominent person, and Kronos and Uranos are inferior and introductory precursors, set up in order to be overthrown and to serve as mementos of the prowess of their conqueror. To Homer and Hesiod, as well as to the Greeks universally, Zeus is the great and predominant god, “the father of gods and men,” whose power none of the other gods can hope to resist or even deliberately think of questioning. All the other gods have their specific potency and peculiar sphere of action and duty, with which Zeus does not usually interfere; but it is he who maintains the lineaments of a providential superintendence, as well over the phenomena of Olympus as over those of earth.” 20

According to their mythical stories, Zeus bears to man the relation of ‘father.’ Each mortal who had a supplication to make to him, addressed him as ‘god (our) Father’. He bears, as one of his most usual titles, the designation of father of gods and men. As St. Paul says quoting a Greek poet, ‘we are his offspring.’ The entire passage recognizes him as having hung the stars in the blue vault of heaven, and having set them there “For signs, and for seasons, and for days, and years.” Such was the strength of Zeus, according to the Greek idea; but withal there was a weakness (He had a material frame, albeit of an ethereal and subtle fiber; and requires material sustenance.) about him, which sinks him, not only below the ‘Almighty’ of Scripture, but even below the Ormazd of the Persians. 21 This alludes to the fact that the Christians, who came centuries later, adopted the son of god concept from the ancient Greeks. In essence, the concept of the ‘offspring of god’ is nonsensical in nature because the offspring itself is a means of support, and any being which needs support or is dependent, can never be a Supreme Being and hence not a God.

Hades

He was the Olympian god of the underworld, son of the Titans Cronus and Rhea, and the brother of Demeter, Hera, Hestia, Poseidon, and Zeus. Hades’ eponymous realm is the underworld, the kingdom of all dead souls. Together with his wife, Persephone, who joins him in ruling the underworld, they are the prime deities of the underworld. The name Hades, according to ancient etymology, meant “invisible”; thus, Hades was sometimes called the ruler of the invisible world, or underworld. His helmet, the cap of Hades, caused its wearers to become invisible. It was used by the hero Perseus when he killed Medusa, and Athena wore it in the Iliad. Hades was sometimes conceived of as the “other Zeus,” but unlike Zeus, no cults were dedicated to him. He was also referred to as Pluto, meaning “wealth,” and this aspect of his characterization was more favorably viewed. The myths concerning Hades were few. In Homer’s Iliad, Hades was wounded by Heracles during an encounter in Pylos. The most important myth of Hades was the abduction of Persephone. The abduction of Demeter’s daughter Persephone was vividly described in Ovid’s Metamorphoses: Hades seized the girl from among her maiden companions in a Sicilian meadow. Demeter refused to return to Olympus but wandered over the earth, seeking her daughter. In her grief, she neglected the harvest, and a famine ensued. Finally, Zeus persuaded Hades to return Persephone, but she had eaten one or more pomegranate seeds while in the underworld, and she was fated to remain there for part of every year. Persephone’s time in the underworld coincides with winter, and her reappearance above with spring and summer. 22 Beliefs like these truly depict the lowliness of the human mind. Associating such a deed with a normal human being is extremely insulting, hence it seems baffling that a sane mind can associate such acts with a God.

Aphrodite

Encyclopedia Britannica described her as the ‘Ancient Greek goddess of sexual love and beauty’ who was identified as Venus by the Romans. 23 Kaile Dutton, while giving further details on Aphrodite, quoted that she was the most beautiful of all Greek goddesses and her primary role was to bring love to this world. 24

The Encyclopedia of the ancient Greek world described Aphrodite the ancient Greek goddess of love, sex, fertility, rebirth, and physical beauty. She was also closely associated with the sea. She was one of several deities (along with Zeus, Athena, and Apollo) whose earthly influence was most celebrated in Greek art and poetry. Not surprisingly, Aphrodite was also considered to be the patron deity of prostitutes. Her temple at Corinth was famous in Roman times for its sacred prostitutes, whose fees went to the sacred treasury. This feature seems to have been unique in a Greek cult and quite abhorrent in reality. Traits like these gave license to open prostitution which lead to the destruction of familial systems and then the society. Celebrating prostitution as a religious ritual shows the moral corruption of the ancient Greeks rather than their greatness (as understood and endorsed by various so-called scholars of social sciences whose polices have led more towards social, political and moral destruction). Such derogatory beliefs regarding the concept of God probably developed in the prosperous harbor city of Corinth because of the Syrian-Phoenician influence that arose in the 700s B.C. through trade and commerce.

The origin of the name Aphrodite is unknown; the Greeks explained it as meaning ‘foam-born.’ A passage in Hesiod’s epic poem the Theogony (700 B.C.) tells the best-known version of her birth. The primeval god Cronus severed the genitals of his father, Uranus, and threw them into the sea. There, they generated a white foam (Greek: aphros). The goddess arose from this foam, fully formed, and stepped ashore at Cyprus. There is also another version of her birth, told in Homer’s epic Iliad and Odyssey, written down perhaps 50 years before Hesiod’s time. There, Aphrodite is said to be the daughter of Zeus and the ocean nymph Dione. 25

Apollo

Edwards Franks stated that he was variously recognized as the god of music, truth and prophecy, as well as the healer of the sun, light, plague, poetry and more. 26 He was a god worshipped throughout the Greek world, and was the embodiment of moral excellence and of young, but mature, male beauty. He had many diverse functions: he was a god of music (especially the lyre), of prophecy, healing, archery (but not war or hunting) and of the care of herds and flocks. He was also a god of light (sometimes being identified with the Sun and with the god Helios). Despite being a god of healing and medicine, he was also the god of plague. He was usually associated with what were regarded as the higher developments of civilization, such as moral and religious principles, philosophy and law.

In mythology Apollo was an Olympian, the son of Zeus and Leto and the twin brother of Artemis. Many legends concerned Apollo’s numerous spheres of influence. One related how he seized Delphi by destroying the Python, an early deity that appears to have been absorbed by Apollo, giving rise to the Pythian Apollo of the Delphic Oracle. Apollo was generally regarded as politically neutral, but he is shown favoring the Trojans in Homer’s Iliad. The Delphic Oracle was not always neutral, however, and favored the Persians during the Persian Wars and the Spartans during the Peloponnesian War. 27

Ares

As per Greek and Roman mythology, Ares, the god of war, was bloody and brutal. Such was his brutality that his father Zeus (in Homer’s Iliad) declared that he hated his son for his perpetual violence and aggression. 28

It has been well said that Ares was ‘the impersonation of a passion.’ That combative propensity, which man possessed in common with a large number of animals, was regarded by the Greeks, not only as a divine thing, but as a thing of such lofty divinity that its representative must have a place among the deities of the first class or order. The propensity itself was viewed as common to man with the gods, and as having led to “wars in heaven," wherein all the greater deities had borne their part. Now that peace was established in the Olympian abode, it found a vent on earth, and caused the participation of the gods in the wars carried on among mortals. Ares was made the son of Zeus and Hera, the king and queen of heaven. He was represented as tall, handsome, and active, but as cruel, lawless, and greedy of blood. The finer elements of the warlike spirit were not his. He was a divine Ajax, rather than a divine Achilles; and the position which he occupied in the Olympian circle was low. Apollo and Athena were both entitled to give him their orders; and Athena scolded him, striked him senseless, and wounded him through the spear of Diomed. His worship was thought to have been derived from Thrace, and to have been introduced into Greece only little before the time of Homer. 29

Artemis

Artemis, in Greek religion, was the goddess of wild animals, hunt, vegetation, and of chastity and childbirth. She was identified by the Romans with Diana. Artemis was the daughter of Zeus and Leto and the twin sister of Apollo. Among the rural populace, Artemis was the favorite goddess. Her character and function varied greatly from place to place, however, behind all forms lay the goddess of wild nature, who danced, usually accompanied by nymphs, in mountains, forests, and marshes. Artemis embodied the sportsman’s ideal, so besides killing game she also protected it, especially the young; this was the Homeric significance of the title Mistress of Animals.

The worship of Artemis probably flourished in Crete or on the Greek mainland in pre-Hellenic times. Many of Artemis’ local cults, however, preserved traces of other deities, often with Greek names, suggesting that, upon adopting her, the Greeks identified Artemis with nature divinities of their own. 30

Athena

Athena was a powerful goddess in Greek mythology. She was the goddess of wisdom, war and the useful arts. The useful arts included spinning, weaving and playing music. 31 Adolf Holm gave her description as:

“First and foremost, in this class is Athene, who originally no doubt was the goddess of the waters of heaven and of the phenomena producing and accompanying them. She was born from the head of Zeus, by a blow from a hatchet dealt by Hephaestus or Prometheus. She is the goddess of the thunderstorm she brandishes the thunderbolt, and is hence called Pallas or the Wielder. She wears as her peculiar adornment and defense the Aegis, a shield with the head of the Gorgon on it. The Gorgon is the thunder- cloud, the tongue- darting serpents surrounding the head are the lightning flashes, which burst forth in all directions. Athene is called Glaucopis, the owl- eyed, probably because she is also the goddess of the clear sky, which has been made bright by the purifying storm, and because the sight of the owl pierces the darkness. In the realm of morals, she is the divinity who drives away gloom and Oppression, the goddess of clear understanding, of wisdom, and of skill in art, and lastly, the intelligent protector of man against his foes, and so the goddess of defense, while Ares is more the god of impetuous attack. Athene was never so loyally worshipped, not even in Thessaly or Boeotia, as in the city which bore her name, which strove to make its inward character a reflection of that of the goddess”. 32

Demeter

She was the goddess of agriculture. Daughter of the Titans Cronus and Rhea. Demeter’s Olympian siblings were Hades, Hera, Hestia, Poseidon, and Zeus. Demeter was associated with the fertility of crops, especially of grain. Later, the Romans syncretized her with the goddess Ceres. In the Theogony, the Homeric Hymn, and the Odyssey, Demeter loved the hero Iasion, and their son Ploutos (meaning “wealth”) was conceived, appropriately considering her sphere of activity, on a thrice-plowed field. In some accounts, when Zeus became aware of their affair, he struck Iasion dead with a thunderbolt, on the grounds that a mortal was not to have such relations with a god. In other accounts, Iasion survived. Demeter’s brother Poseidon forced himself upon her, and she became pregnant with two children, Despoine, a goddess worshipped in the Eleusian Mysteries, and Aerion, a dark-colored horse, because when Poseidon came upon her, Demeter had transformed herself into a mare in an unsuccessful attempt to avoid his advances. Demeter was the fourth wife of her brother Zeus, and their daughter was Persephone, with whom Demeter is closely associated in mythology and cult practice.

Central to the Demeter myth was the abduction of her daughter Persephone by Hades, and her imprisonment in the underworld. Demeter, disguised as an old woman, searched the world in vain for her daughter. Though no one had seen Persephone, many offered the disguised goddess comfort or food. In return for their kindness, Demeter taught them agriculture and initiated them into her rites.33

Hephaestus

The ancient Greek god Hephaestus was known as the “Vulcan” in Rome and “Vishvakarma” in India. 34 Hephaestus was the god of fire, and especially of his connection with smelting and metallurgy. He dwelled in Lemnos, where he habitually forged thunderbolts for Zeus, and occasionally produced fabrics in metal of elaborate and exquisite construction. Among the most marvelous of his works were the automatic tripods of Olympus and the bronze maidens, whom he had formed to be his attendants on account of his lameness. He was the armorer of heaven, and provided the gods generally with the weapons which they used in warfare. The peculiarity of his lameness was strange and abnormal, since the Greeks hated deformity, and represented their deities generally as possessed of perfect physical beauty. 35 This concept itself was contradictory because the capacity of the human mind is limited, which is itself a deformity. Secondly, when something itself is imperfect, then it is impossible for that thing to create any minor thing with perfection. Therefore, their skills in sculpting may be praised, but their ideas were delusional to the core.

Poseidon

Poseidon was defined as god of the sea. 36 Also known as the mighty Poseidon, the earth-shaker and the ruler of the sea, he was second only to Zeus in power but had no share in those imperial and superintending capacities which the Father of Gods and men exhibited. 37 His chief role was to cause storms or calm the waters. His wife was Amphitrite. There were often tensions between Poseidon and his brother Zeus. Poseidon joined Hera and Athena’s conspiracy to put Zeus in chains and, in the Iliad, often insisted on asserting his independent authority. According to Homer, Poseidon supported the Greeks in the Trojan War and continued to do so actively, even after Zeus forbade the other Olympians from interfering with the war Unlike Zeus, Poseidon was not associated with human society and institutions but with violent natural phenomena such as the sea and earthquakes. He wielded the trident and rides a chariot through the waves. 38

He was worshipped as god of fresh water and was considered a tamer of horses as well, therefore he was often worshipped as Poseidon Hippios (Poseidon of Horses). In Athens the eighth day of every month was sacred to Poseidon. The Isthmian Games were held every two years on the Isthmus of Corinth in his honor. Sacrifices to Poseidon by the Attic deme Erchia were held on the 27th day of the month Gamelion and on the third day of the month Skirophorion. 39

Hermes

Hermes (Roman name: Mercury) was the ancient Greek god of trade, wealth, luck, fertility, animal husbandry, sleep, language, thieves, and travel. One of the cleverest and most mischievous of the Olympian gods, he was also their herald and messenger. With origins as an Arcadian fertility god, the ancient Greeks believed he was the son of Zeus and Maia (daughter of the Titan Atlas). In mythology, Hermes was also the father of the pastoral god Pan and Eudoros (with Polymele), one of the leaders of the Myrmidons.

Hermes was also known as something of a trickster, stealing at one time or another Poseidon’s trident, Artemis’ arrows, and Aphrodite’s girdle. He was also credited with inventing fire, dice (and so was worshipped by gamblers in his capacity as god of luck and wealth), musical instruments, in particular, the lyre (made from a tortoise shell), and the alphabet. Famous for his diplomatic skills, he was also regarded as the patron of languages and rhetoric. 40

Hestia

She was the goddess of the hearth. Daughter of the Titans Cronus and Rhea. Hestia was associated with domesticity. She was a virgin goddess and, like Artemis and Athena, immune to love. Hestia personified the hearth and was associated generally with the home and the family, but she had no myths of her own. 41

The hearth was the symbol of home and family, and the prytaneion 42 in many cities had a public hearth dedicated to Hestia, with a fire kept constantly burning. If a city founded a colony, fire was taken from the public hearth to it. One of Hestia’s titles was Boulaia (of the council), and many bouleuteria had public hearths. Sacrifices began with libations to Hestia, and she was generally mentioned first in prayers and oaths. Meals began with small offerings thrown into the domestic fire. Pigs and occasionally cows were sacrificed to Hestia. At five days old children were formally accepted into the family; as part of the ceremony someone carrying the child ran around the hearth. Temples dedicated to Hestia were characteristically circular in form. 43

The ancient Greeks were known for their understanding of philosophy and many other fields, but upon reading their views regarding religion and society, one is baffled to know the primitiveness and dunderheadedness of their thinking. One does not need a miracle to understand the fact the sole reason behind the peace of the universe is the monotheistic existence of a Supreme Being who is matchless in every way. The only people who preached this message were the divinely designated prophets whose names are mentioned in sacred books of divinely revealed religions.

All the prophets including Prophet Muhammad  completely refuted all the false beliefs about God and conveyed the message of Allah to all humanity. It takes simple common sense to decide whether a person should go for the different incomplete, immoral, un-just, nonsensical mess of concocted theories presented by pseudo-religious leaders, which they categorized as ‘religion’ or follow the message propagated by the divinely guided prophets who gave the same message over a period of thousands of years which also guaranteed prosperity, peace, love, justice and morality. Examples of such societies can be seen in the societies formed by Prophet Moses

completely refuted all the false beliefs about God and conveyed the message of Allah to all humanity. It takes simple common sense to decide whether a person should go for the different incomplete, immoral, un-just, nonsensical mess of concocted theories presented by pseudo-religious leaders, which they categorized as ‘religion’ or follow the message propagated by the divinely guided prophets who gave the same message over a period of thousands of years which also guaranteed prosperity, peace, love, justice and morality. Examples of such societies can be seen in the societies formed by Prophet Moses  , David

, David  , Solomon

, Solomon  , and Prophet Muhammad

, and Prophet Muhammad  in which people from every religion found peace, love, justice and prosperity.

in which people from every religion found peace, love, justice and prosperity.

Ancestry of the Greek Gods

The lineage of the Greek gods can be seen in the following chart: 44

According to Holm, the status of Zeus near Greek was: “The chief deity was Zeus, the conception of whom arose originally from the contemplation of the clear sky. The sky extended over all things, and ruled all things by the phenomena which proceeded from it. And because the sky did not always shine in tranquil splendor, so Zeus was not merely a benign ruler, but also a mighty and awe-inspiring deity, who sends forth the thunderstorm and hurled the lightning. At a time, when his rule was contested, he used the lightning in the struggle of the gods against the Titans, who were flung to the ground and swallowed up by the earth, which they thenceforward convulsed as spirits of earthquakes. But Zeus held in his hands not only the fire of heaven, but also the waters thereof; he was called the Cloud-Compeller, the Dodonian Zeus, one of the most revered, being especially worshipped as the rain-bringer. From Zeus proceeded also the rivers; not far from the Dodona flowed the river Achelous, considered the most important of all. The elementary force of water was also specially presented by Oceanus, the immediate origin of rivers; the Styx was described as the eldest daughter of Oceanus. The mountain peaks were dedicated to the chief god, and then to the gods generally; the loftiest mountains in Greek eyes was Olympus, situated on the northern border-line of their territory, and attaining a height of 9750 feet. On its mysterious cloud-girt summit the gods were believed to dwell. In the same way the lofty Ithome and the mountain peaks of Arcadia and Crete were sacred abodes of Zeus. The Plain of Olympia was probably not dedicated to the supreme god till later, in consequence perhaps of an agreement between Greeks of different districts. He was joined with his consort Hera, the goddess of heaven who was also called Dione or Diaina and was worshipped on the mountain Euboea near Argos. 45

The Iliad and Odyssey introduced us to the immense family of the Greek gods, dwelling on snow-capped Mount Olympus at the northern edge of Greece, ruled by Greece and his consort Hera, intervening incessantly in human affairs. Poseidon, the sea-god drives Odysseus on his wanderings, and Hephaestus is the god of forge. The Greeks attributed the movements of the sun to Apollo, and storms at sea to Poseidon. They thought that human wisdom came from Athena, goddess of wisdom; victory in battle from Ares, the war-god; and success in love from Aphrodite. These gods were no remote and perfect deities. The Olympus depicted by Homer is not so much one big happy family as a collection of unruly, jealous, brawling individuals who also manage to be engaging and attractive. 46

So, the Greek gods were always fighting amongst each other, were unruly, and jealous, hence they were imperfect. Consequently, their followers also adopted the traits of their deities and played a major role in causing chaos in the society.

Ambrosia

When we look into the accounts of many different mythologies and religions, it becomes clear that the gods were either immortal or lived a life of many thousands of years. What is rarely mentioned is the fact that in ancient religious texts there is reference to their immortality or longevity being connected to a specific kind of food that only the forged gods were allowed to eat. The gods were required to eat this food regularly to maintain immortality, power and strength. Many references also refer to the fact that if mortals ate this food, they would also become immortal like the gods. This food was also known as the ‘Elixir of Life’. One of the main references to the food of the immortals can be found in Greek mythology. It has been written in the stories of the Greek gods that ambrosia and nectar was the food and drink of the immortal gods and this first appeared in the Greek mythology relating to the birth of Zeus. Before the ‘invention’ or ‘discovery’ of ambrosia and nectar by the gods, it was written that they would feed by ‘sniffing’ the vapors of their dead enemies, as if they would feed from the energy of the dead souls. 47

About the food of the gods, Adolf Holms stated:

“India and Greece both have a drink for the gods, in the former called soma, in the latter nectar or ambrosia.”48

Ambrosia was the food of the gods, which conferred upon them eternal youth and immortality, and was brought to Zeus by pigeons. It was also used by gods for anointing their body and hair. 49 This ambrosial food was necessary for the Greek gods, George Rawlinson portrays its importance in the following manner:

“For, though secure from dissolution, though surpassingly beautiful and strong, and warmed with a purer blood than fills the veins of men, their heavenly frames are not insensible to pleasure and pain; they need the refreshment of ambrosial food, and inhale a grateful savor from the sacrifices of their worshippers.”50

Concept of Afterlife

In ancient Greece the continued existence of the dead depended on their constant remembrance by the living. By the time of Plato, however (4th century B.C.) the afterlife had changed in character so that souls were better rewarded for their pains once they had left the earth; but only in so much as the living kept their memory alive. The afterlife was known as Hades and was a grey world ruled by the Lord of the Dead, also known as Hades. Within this misty realm, however, were different planes of existence the dead could inhabit. If they had lived a good life and were remembered by the living, they could enjoy the sunny pleasures of Elysium; if they were wicked then they fell into the darker pits of Tartarus while, if they were forgotten, they wandered eternally in the bleakness of the land of Hades.51

According to the Greeks, souls could return to earth as ghosts, but most souls, most of the time, stayed in the underground kingdom called Hades, which was ruled over Hades by his queen, Persephone. In earliest times, the Greeks seem to have believed that everyone there was treated in the same way. The souls existed in a state that was neither pleasant nor unpleasant; literary portrayals, such as that in Book 11 of the Odyssey, suggest that the underworld was dank and dark, and that there was little to do to pass eternal time. In the Odyssey and elsewhere, souls usually were portrayed as looking like their former bodies (thus women who were famous beauties while alive remained attractive, and mighty warriors still wore their armor). Souls also retained the desires and grudges they held while alive.

A few people do suffer punishment in a special part of the underworld according to the Odyssey and other Greek literary texts, although it is not clear whether the Greeks considered them to be truly dead or to have been transported to the underworld while still alive. Among the most famous are Tantalos, who endured eternal thirst and hunger, and Sisyphos, who was doomed to push a boulder uphill repeatedly. But these were unusual cases of people who had done unusually wicked things; there was no indication that the average person expected to be punished after death. There were also examples, in myth, of people who got extraordinary rewards at the end of their lives, due to their special relationships with the gods. Menelaus, Helen's husband and therefore Zeus's son-in-law, knew he would be carried off to the paradisiacal Elysian Fields at the end of his life, for example, instead of dying. 52

Devoid of the religious text, and prophets, ‘the Great Greeks’ who are known for their mundane innovations, failed to decipher the truth of their creator. They should be credited for their one achievement though. They were aware that they were ‘created’ by a creator, and did not evolve from some lowly creature.

The ancient Greeks were polytheistic like the other civilizations of the world, and separate statues and temples were made for each deity where the participants performed their rituals and offered sacrifice. We also saw that with time, the number of their deities kept on increasing, from titan worship to the Olympians to the worship of heroes. Their list of deities was never ending, and their beliefs were superstitious and faulty because this religion was created by the Greek people themselves. A normal human mind is only able to grasp the concepts which can be received through the five senses, hence the boundaries of the brain are limited. Hence any religion which is made by man, will remain faulty.

The same was the problems with the Greeks, to fulfill their need of a god, they looked at things which seemed to be superior to them. If they saw that quality in a human, e.g. an unbeatable warrior, they made it their god. If they couldn’t find anything, then they created things out of their imagination. Then to appease that god, they performed various rituals which never benefited them in any way. They used to dance, drink wine, slaughtered animals etc. to make their gods happy which was their own understanding but was of no use in reality.

The case of idolatry was not only pertinent to ancient Greece. At that time, a major part of the world was in practice of polytheistic religions. In some areas, kings and even lowly creatures such as snakes, cats, monkey, elephants etc. were worshipped like the Hindus who practice it till date. Only those people who had direct or indirect access to a divine prophet or divine guidance were able attain guidance and live prosperously. The religions concocted by humans were plagued with personal benefits and satanic influence hence their proposed faiths were designed to the divide humanity, whereas the divine guidance brought by Prophet Adam  till Prophet Muhammad

till Prophet Muhammad  remained the same i.e. submission to the will of only One God who was the Supreme Being. History has shown that people who believed in these divine teachings became the most prosperous people on this planet.

remained the same i.e. submission to the will of only One God who was the Supreme Being. History has shown that people who believed in these divine teachings became the most prosperous people on this planet.

- 1 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 310.

- 2 Syed Hashmi Fareedabadi, Tareekh Yunan Qadeem, Institute of Aligarh, Aligarh, India, Pg. 26.

- 3 Ghulam Bari (1949), Tareekh ka Muta’ala, Maktaba Urdu, Lahore, Pakistan, Pg. 184-185.

- 4 Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Online Version): http://www.iep.utm.edu/xenoph/#SH3a: Retrieved: 07-06-17

- 5 David Sacks, Revised by Lisa R. Brody (2005), Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World (Revised Edition), Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 291.

- 6 Aristotle, Metaphysics: L.11, C.7. Pg. 306: http://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/03d/-384_322, _Aris toteles, _Metaphysics, _EN.pdf 03d/-384_322, _Aris toteles, _Metaphysics, _EN.pdf : Retrieved 16-03-17

- 7 Jane Ellen Harrison (1913), The Religion of Ancient Greece, Constable & Company Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 17.

- 8 The human soul and the body, both are created, and the created can never be the creator because the human body and soul, both are dependent whereas God is not contingent upon on any other being. And any being which depends on another, is ultimately not God and no matter how much that being tries, he will still remain the created.

- 9 Daniel Ogden (2007), A Companion to Greek Religion, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, U.K, Pg. 386-387.

- 10 Habib Haq (2015), Yunani Tehzeeb ki Dastaan, Nigarasht Publisher, Lahore, Pakistan, Pg. 187-188.

- 11 Adolf Holm (1894), The History of Ancient Greece (Its commencement to the close of Independence of Greek Nation, Macmillan and Co., London, U.K, Vol. 1, Pg. 122-123.

- 12 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 310-311.

- 13 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/topic/Greek-religion: Retrieved: 13-04-19

- 14 W. Den Boer (1973), Harvard Studies in Classical Philology: Aspects of Religion in Classical Greece, Harvard University, Massachusetts, USA, Vol. 77, Pg. 1.

- 15 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 310-311.

- 16 T. T. Timayenis (1882), History of Greece, from the Earliest times to the Present, D. Appelton and Company, New York, USA, Vol. 1, Pg. 2-3.

- 17 Daniel Ogden (2007), A Companion to Greek Religion, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, U.K, Pg. 43.

- 18 Herodotus (1954), The Histories, Penguin Books Ltd., Harmondsworth, Middlesex, U.K., Part 2, Pg. 43-44.

- 19 George Grote (1851), History of Greece, John Murray, London, U.K, Vol. 1, Pg. 14.

- 20 George Grote (1851), History of Greece, John Murray, London, U.K., Vol.1, Pg. 2-4.

- 21 George Rawlinson (1883), The Religion of the Ancient World, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, USA, Pg. 184-185.

- 22 Luke Roman and Monica Roman (2010), Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman Mythology, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 91-192.

- 23 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/topic/Aphrodite-Greek-mythology: Retrieved: 18-03-17

- 24 Anna Haywood (2013), Love Craft: Divine, Cast and Decode Your Way to Love with The Power of Astrology, Numerology, Spells Potions, And More, Adams Media, Avon Massachusetts, USA, Pg. 81-82.

- 25 David Sacks, Revised by Lisa R. Brody (2005), Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World, (Revised Edition), Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 33-34.

- 26 W. S. Gilbert & Ian C. Bradley (2016), The Complete annotated Gilbert and Sullivan, Oxford University Press, UK, Pg. 10.

- 27 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 316-317.

- 28 Kathleen N. Daly & Marian Rengel (2009), Greek and Roman Mythology, InfoBase Publishing, New York, USA, Pg. 16.

- 29 George Rawlinson (1883), The Religion of the Ancient World, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, USA, Pg. 140-141.

- 30 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/topic/Artemis-Greek-goddess: Retrieved 18-3-17

- 31 Nancy Loewen (1999), Athena: Greek and Roman Mythology, Capstone, Mankato, Massachusetts, USA, Pg. 15.

- 32 Adolf Holm (1894), The History of Ancient Greece: Its commencement to the close of Independence of Greek Nation, Macmillan and Co., London, U.K. Vol. 1, Pg. 126.

- 33 Luke Roman and Monica Roman (2010), Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman Mythology, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 132.

- 34 Vaid Vashish (2012), The Codified Mysteries, Lulu.com, North Carolina, USA, Pg. 165.

- 35 George Rawlinson (1883), The Religion of the Ancient World, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, USA, Pg. 141-142.

- 36 Bukert Walter (1985), Greek Religion, Harvard University Press, Massachusetts, USA, Pg. 136.

- 37 George Grote (1851), History of Greece, John Murray, London, U.K, Vol. 1, Pg. 76.

- 38 Luke Roman and Monica Roman (2010), Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman Mythology, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 418.

- 39 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 354.

- 40 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version) : http://www.ancient.eu/Hermes/ : Retrieved 18-03-201s7

- 41 Luke Roman &Monica Roman (2010), Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman Mythology, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 234.

- 42 Prytaneum, Greek Prytaneion, town hall of a Greek city-state, normally housing the chief magistrate and the common altar or hearth of the community. [Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version):https://www.britannica.com/technology/prytaneum : Retrieved: 23-10-2019

- 43 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 339.

- 44 Wikipedia (the Free Encyclopedia): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Family_tree_of_the_Greek_gods : Retrieved 18-03-2017

- 45 Adolf Holm (1894), The History of Ancient Greece: Its commencement to the close of Independence of Greek Nation, Macmillan and Co., London, U.K., Vol. 1, Pg. 124-125.

- 46 Crane Brinton (1955), A History of Civilization, Prentice Hall Inc., New York, USA, Vol.1, Pg. 52-53.

- 47 Ancient Origins: https://www.ancient-origins.net/myths-legends/immortality-elixir-life-and-food-gods-001201: Retrieved 18-03-2017

- 48 Adolf Holm (1894), The History of Ancient Greece: Its commencement to the close of Independence of Greek Nation, Macmillan and Co, London, U.K., Vol. 1, Pg. 20.

- 49 William Smith (1845), School Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities London, U.K., Pg. 19.

- 50 George Rawlinson (1883), The Religion of the Ancient World, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, USA, Pg. 135.

- 51 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): https://www.ancient.eu/article/29/ : Retrieved 22-03-17

- 52 Afterlife: Greek and Roman Concepts: https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias- almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/afterlife-greek-and-roman-concepts : Retrieved 22-03-2017