Life Style of Greece – Social Customs of Ancient Greeks

Published on: 12-Jun-2024(Cite: Hamdani, Mufti Shah Rafi Uddin & Khan, Dr. (Mufti) Imran. (2020), Life Style of Ancient Greece, Encyclopedia of Muhammad  , Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 158-196.)

, Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 158-196.)

To unearth the lifestyle of any civilization, one must take a look at the archeological evidence, researches and other available information on the matter. In the case of Greece, the historical evidence is available in the form of poems by Homer and other poets, some documents by Herodotus and other historians, and some artifacts of the ancient times. The historical evidence showed us that the Greeks who appeared to be one of the eminent people of ancient times, were unable to avoid the traps set for them by the devil. Instead, they followed in his footsteps and adopted his teachings in their religion, culture, politics and everyday life.

Despite the splendid work of Schliemann 1 and other archeologists, the formative centuries of Greek civilization remain one of the most obscure periods of ancient history. Fortunately, the Homeric epics do provide material on the character and the institutions of the early Greeks. The Iliad and the Odyssey were written probably in the ninth or eight centuries before Christ (though perhaps somewhat earlier); they may have been the work of the blind poet from Asia Minor called Homer or of several unknown poets. The Homeric epics therefore, furnish a description of early Greeks. 2

Before moving forward, one should know that Greece was not a single unified country, it was a collection of cities or city states. The term “city-state” is a modern coinage, yet city-states themselves are ancient political formations, going back to the Early Bronze Age in Mesopotamia. Basically, a city-state is a defined geographical area comprising a central city and its adjacent territory, which together make up a single, self-governing political unit. The Greeks called this arrangement a polis, which gives us “political,” “politics” and “policy”. 3

Dorians and Ionians came to be the leading races in Greece. Their diverse characteristics had a great influence on its history. The Dorians were rough and plain in their habits, sticklers for the old customs, friends of aristocracy, and bitter enemies of trade and fine arts. The Ionians, on the other hand, were refined in their tastes, fond of change, democratic, commercial, and passionate lovers of music, painting, and sculpture. The rival cities, Sparta and Athens, represented these opposing traits. Their deep-rooted hatred was the cause of numerous wars which convulsed the country. For, in this sequel, we shall find that the Grecians spent their best blood in fighting among themselves, and Grecian history is mostly occupied with the doings of these two cities. 4

If you were to look at a map of Greece which distinguished the states, and not the meaningless ethnical or tribal divisions of the people, you would observe that from the outset Sparta and Athens were destined to greatness, if by nothing else, by the size and material resources of their territories. 5

Athens

The word acropolis comes from the Greek “akro” (“high”) and “polis” (“city”). It generally refers to a hilltop citadel and was a vital feature of most ancient Greek cities, providing both a refuge from attack and an elevated area of religious sanctity. The best-known acropolis is at Athens, where a magnificent collection of temples and monuments, built in the second half of the fifth century B.C.E., remains partially standing today. The most famous of these buildings is the Parthenon, the temple of Athena Parthenos (the maiden).

Most early societies naturally concentrated their settlements on raised areas, less vulnerable to attack than low-lying sites. In ancient Greece the royal palaces of the Mycenaean Civilization arose on the choicest of these hills (1600–1200 B.C). The Mycenaean Greeks favored hilltops close to agricultural plains and not too near the sea, for fear of pirate raids. Typical Mycenaean sites include Mycenae, Tiryns, Athens, and Colophon (meaning “hilltop”), a Greek city in Asia Minor. 6

Athens, the capital of Attica, the metropolis of ancient Greek culture, took its name, plausibly, from Athena ‘goddess of science, arts, and arms,’ who from earliest times was the patron divinity of the city. Athens owes its original location, doubtless, to the craggy rock known as the Acropolis that rises more than 500 feet high above the Attic plain, and that in earliest days served for citadel as well as for residence and site of sanctuaries. With the growth of the population, the parts below and adjacent to the Acropolis, especially on the western and southern slopes, became inhabited. However, prior to this earliest period in the history of Athens as a Greek city, it is held by many that there was a settlement of Phoenicians on the Slopes of the hills towards the sea, numerous remains of which, in the form of cellars, cisterns, graves, steps, seats, all cut into the native rock, are still to be seen, constituting what is generally known as ‘The Rock City.’ 7

Sparta

Sparta was a beautiful town near the river Evrotas, located in the center of the Peloponnese in southern Greece, is the capital of the prefecture of Lakonia. Sparta (known in Greek as Sparti) has a history which dates back to the Neolithic period, at least 3,000 years before Christ. Even in its most prosperous days, it was merely a group of five villages with simple houses and a few public buildings. The passes leading into the valley of the Evrotas were easily defended, and Sparta had no walls until the end of the 4th century BC. 8

Around Arcadia seven districts were situated, almost all of which were well watered by streams that descended from its highlands. In the south lay the land of heroes, Laconia, rough and mountainous, but thickly settled; so that it is said to have contained nearly a hundred towns or villages. It was watered by the Eurotas, the clearest and purest of all the Grecian rivers, of which had its rise in Arcadia, and was increased by several smaller streams. Sparta was built upon its banks, the mistress of the country without walls and gates, defended only by its citizens. It was one of the larger cities of Greece; but, notwithstanding the market-place, the theatre, and the various temples which Pausanias enumerates, it was not one of the most splendid. 9

In Greek mythology the founder of the city was Lacedaemon, a son of Zeus, who gave his name to the region and his wife’s name to the city. Sparta was also an important member of the Greek force which participated in the Trojan War. Sparta was located in the fertile Eurotas valley of Laconia in the southeast Peloponnese. The area was first settled in the Neolithic period and an important settlement developed in the Bronze Age. Archaeological evidence, however, suggests that Sparta itself was a new settlement created from the 10th century BC.

In the late 8th century BC, Sparta subjugated most of neighboring Messenia and its population was made to serve Spartan’s interests. Sparta thus came to control some 8,500 km² of territory making the polis or city-state the largest in Greece and a major player in Greek politics. The conquered peoples of Messenia and Laconia, known as perioikoi, had no political rights in Sparta and were often made to serve with the Spartan army. A second and lower social group was the helots, semi-enslaved agricultural laborers who lived on Spartan-owned estates. 10

Population

In the age of Pericles, Athens was a city with a population of about 150,000. Attica, the territory of the Athenians, had an approximately equal number of inhabitants. Of the 300,000 thus accounted for, about one third was servile (slaves) and one sixth foreign. The free and franchised population made up one half of the total, and yielded about 50,000 males of military age. The empire of the Athenians consisted of five provinces, the Thracian, Hellespontine, Insular, Ionian, and Carian, with a total population of perhaps, 2,000,000. It formed a complex of islands, peninsulas, and estuaries, the most remote extremities of which were distant two hundred or two hundred and fifty miles from Athens. 11

Spartan’s inhabitants were classified as Spartiates (Spartan citizens, who enjoyed full rights), mothakes (non-Spartan free men raised as Spartans), perioikoi (freedmen), and helots (state-owned serfs, enslaved non-Spartan local population). At its peak around 500 B.C. the size of the city would have been some 20,000 – 35,000 free residents, plus numerous helots and perioikoi (“dwellers around”). 12 At 40,000 – 50,000 it was one of the largest Greek cities. 13

The other Greek city-states rarely had populations as many as 40,000 people. As a general rule, as soon as a city approached a population of 20,000 to 30,000, it decided to find a new city rather than to continue the original city's development.

Hellenic race had in common the simple ideal of living the noble life and this to a Greek meant rather the negation of certain things than the assertion of definite intentions. Life was not to be standardized into rigid formulae "men were not to be ruled by blind authority or by self- imposed potentates the city they inhabited was not to consist of a royal palace and its dependent outhouses, like Mycenae, where the dynasts lived on the highest and finest parts of the town and the servile population in what was left. Cretan Knossos, Babylon, and all the great cities of the old Principalities were not fit habitations for the free Hellene, to whom life in a city meant that he could go where he willed and when he willed. So, the true Hellenic city from the earliest time differed radically from all types of city that had preceded it. 14

Calendar

All Greek city states had 12 months, with alternate months having 29 days (hollow months) or 30 days (full months), all beginning with the new moon. The lunar month (the period between one new moon and the next) measured 291/2 days, but the yearly cycle of the Earth around the Sun was about 3651/4 days (about 11 days longer than 12 lunar months). All calendars were originally lunar, but they also had to be reconciled with the solar year, otherwise the months would slip according to the season. This was done by intercalation— inserting an extra month (in Athens usually another Poseideon) in the year or extra days within the month. Each state had a different system, but it was common for alternate years to have an extra 30 days, with alternate years of 354 and 384 days. This system still led to discrepancies, and astronomers devised astronomical cycles to control the intercalation. Magistrates were responsible for bringing the lunar months in line with the seasons (in particular so that festivals could be held at appropriate times), but there was no evidence that astronomical methods were used in civil calendars until Hellenistic times. The Greek calendar had the following names (given with approximate modern equivalents):

Hekatombaion (June–July)

Metageitnion (July–August)

Boedromion (August–September)

Pyanopsion (September–October)

Maimakterion (October–November)

Poseideon (November–December)

Gamelion (December–January)

Anthesterion (January–February)

Elaphebolion (February–March)

Mounichion (March–April)

Thargelion (April–May)

Skirophorion (May–June). 15

Classes

Ancient discussions of status privilege what we might call a ‘political society’, was categories of the person as defined by the state. In broadest perspective the various political statuses were divided into two groups: natives (citizens, women, and children) and aliens (metics, barbarians, slaves). Status categories were united by their shared subordination and dependence on the citizen. The point was illustrated by the Greek concept of the family, or oikos. The oikos included more than the modern idea of the ‘‘nuclear family.’’ In addition to parents and children, possessions – slaves, livestock, even farm tools – were members of the oikos. What all these members of the oikos had in common was their subjection to the father. The same dependence ideally prevailed in the more general political community. Resident aliens, for example, could not represent themselves in Athenian law courts, but had the protection of the law only on the condition that a citizen protector was willing to stand up and speak on their behalf.

Ancient slaves did not comprise an economic class, but a political status. Athenian slaves had no specialized economic function: they were found in almost every capacity, often working side by side with free men. From the time of Solon, it was illegal for Athenians to enslave Athenians. As a consequence, freedom became a central political ideal and the inalienable characteristic of the citizen, while enslavement of aliens flourished. For this reason, among others it appears that slaves were regarded in the first place as anti-citizens. They obviously had no civic rights, but were at the disposal of their masters – living tools, in Aristotle’s famous phrase. When, on rare occasions, they were manumitted, they assumed the status of metics. Seldom were freedmen or their descendants granted citizenship (the famous exception comes in the fourth century with the family of the freedman banker Pasion).

Resident aliens, metics, had no inherent political rights, and, at least until the latter part of the fifth century, almost no prospect of obtaining them. From the last quarter of the fifth century on, ‘‘naturalization’’ was more frequently attested, but it remained a rare privilege. Certain metics were wealthy and even politically influential; others were poor. They did not comprise, as some have thought, a ‘‘merchant class.’’

Native children and women enjoyed a peculiar, ambivalent status. They were neither outsiders to the political community nor full participants. While they enjoyed the protections of the state, they shared only imperfectly in its management. Children in the ancient world, as in the modern, were excluded from full participation in the political order. Because they would someday become citizens, full participants, however, they did not belong in the same category as metics. Rather, as Aristotle says, they were to be regarded as ‘‘imperfect’’ citizens. Native women likewise were necessarily part of the civic order, though they did not enjoy full participatory political rights. The peculiar status of women was formally recognized with Pericles’ citizenship law of 451 BC. Up to this time citizens had only to be the offspring of an Athenian father. By the law of Pericles, henceforth both parents had to be Athenian, and subsequently it was necessary to establish women’s status. A native Athenian woman might have been well born, even in practical matters powerful and influential, but she still suffered the political disadvantages of her gender. A poor Athenian might have been able to vote, but had less political influence and access to luxury than a prominent metic courtesan. 16

Aristotle and Plato’s View of Slavery

Greece used to deal with slaves in a very cruel manner. Their major scholars like Plato called slaves as human-footed stock which is a proof that savagery was part of their nature. Aristotle said that slaves were servile by nature, but most slaves were once free men and women that quickly found themselves servants in a Greek democracy. Those that served as slaves were often repaying a debt, on the losing side of a war, or considered a slave by birth. In antiquity Athens was a city focused on knowledge and philosophy, yet they found slavery to be an acceptable institution defended by the philosophers themselves. Those that challenged slavery argued more for the unnatural aspects of the master/slave dynamic rather than opposing the institution outright.

Laws referring to slavery were highlighted in both the Platonic Laws and the Attic Laws. Both sets of regulations were specific in stating that slaves were considered property of the owner and thus treated as an extension of the household. In his article Plato and Greek Slavery, Glenn R. Morrow emphasizes some of the important aspects of Attic law as compared to Platonic law. He shows that slaves had no rights of their own, and they could not seek justice in a court nor could they protect themselves if attacked. Some protection was offered to the slaves through moral and religious law, but the judicial rights of protection were left to the master claiming ownership of the slave.

Under Athenian law the slave would receive strips, equivalent to the fine which a freeman would have to pay for a crime. 17 Secondly, in the Platonic law a child would be considered a slave when born to one free and one slave parent, but according to the Attic law a child born with one free and one slave parent would often acquire the status of citizen and therefore be considered free. Finally, both laws had different approaches when dealing with the freemen. Men who were emancipated were still held accountable for fulfilling certain obligations to their former masters. Plato allowed for no concession here: according to his law, if a slave rejects his obligations, his previous master can reclaim ownership. The Attic law allows a negligent slave to enter into a suit with the former master. If the slave wins, he remains free, but should he lose, his emancipation would be void. By referencing the Platonic laws and comparing them to Athenian law we can get a full grasp of the support that Plato offered the institution of slavery. Plato insisted that slaves be kept from leisurely activities and he discouraged the formation of relationships between slaves and their masters. This leads one to believe that he considered slaves to be unworthy of recognition and therefore worthy of only one position in life, that of a servant. His laws seem to set forth justification for the rash treatment of slaves by their masters, whereas men like Aristotle chose to follow a different path in defending slavery.

Aristotle’s theory of natural slavery is highlighted in his works, Politics. The great philosopher made a flawed attempt to justify slavery through a concept not unlike natural selection where one species is found to be superior to another. He highlights the natural separation of men and differentiates them as Greek and non-Greek, those capable of reasoning and those incapables of reasoning. According to Malcolm Heath, in his article Aristotle on Natural Slavery, Aristotle suggested that, “slaves can be responsive to the reasoned instructions of a master, they have no capacity for reasoning autonomously.” Heath continues with the correlation between non-Greeks and those that lack rationality by referring to Aristotle’s association of them with non-human animals.

Aristotle’s rationalization of natural slavery begins with a definition of slavery which states, “…head of households need to acquire the necessities of life, which include tools, both lifeless and living.” Aristotle emphasized the importance of slavery by stating in Politics that, “…parts of household management correspond to the persons who compose the household, and a complete household consists of slaves and freemen.” He continues by saying that “…a possession is an instrument for maintaining life. And so, in the arrangement of the family, a slave is a living possession, and property a number of such instruments; and the servant is himself an instrument which takes precedence of all other instruments.” By definition Aristotle seems to be proclaiming that slaves are necessary tools of the household 18 and thus a justifiable asset to both the master and the master’s estate. As a tool the slave would be used in accordance with the masters’ needs. This meant the slave would be wielded as an instrument of labor to complete work, the master would otherwise have done himself. Aristotle viewed the institution of slavery as a natural part of humanity, but this may have been based on the demand for slave labor in ancient Greece.

In truth we find that not only did slavery exist in ancient Greece, but it was also a thriving business. The city-state’s necessity for slavery may have been compounded with its people’s desire for leisure and luxury and therefore was condoned by great philosophers. It is hard to believe that a democratic society could hold others against their will and force them to perform laborious tasks, but slavery as an institution held sway politically and economically in Athens. Plato criticized those masters who were lenient on their slaves and he stressed the need for masters to rule with a firm hand. Aristotle made attempts to justify slavery and legitimize the need to hold men and women as servants in a society that placed freedom above all else. Ultimately, what we find is that Grecians seem to have adopted slavery to suit their personal needs for meaningful lives: ones that lead to breakthroughs in art, science, politics, and philosophy. It is through this need that slavery was found as justifiable. 19

Condition of Slaves

Ancient civilizations, including Greeks, seldom questioned the ethics of slavery. It was an accepted part of life. In fact, Aristotle argued in Politics that some people are naturally inferior and are fit only for slavery. He said the fact that Greek slaves were usually foreigners made them uncivilized, therefore inferior, and therefore deserving of slavery. 20 If these philosophers and intellectuals had such attitude towards humanity then one can easily understand the view point of a common person from the elite class towards the slaves.

Slavery occurred in Greece from the Bronze Age onwards. Slaves and their children were the property of their owners to be traded like any other commodity. Slaves were sold or rented out by slave dealers, or they could be bought and sold between individuals. They were virtually without rights and were often distinguished from serfs and other workers as “chattel slaves,” being the property of their owners. They were regarded as “living tools” and were supplied from several sources, primarily warfare and piracy (where they could have been previously free citizens).

Slavery was indispensable to Greek society. Craftsmen and tradesmen aimed to have at least one slave to train in their business so that the work would be continued by the slave on their retirement. Slaves could also be leased out to industrial establishments, providing a profit for their owners. A number of slaves were also owned by towns and cities to undertake public works. 21

The majority of slaves in Athens, for example, were not Athenians, and generally there was a great mixture of nationalities. They were foreign, war captives or the wives and children of the Greeks’ slain enemies. But sometimes Greeks, such as the Spartans and the Messenians, enslaved fellow Greeks following a raid or battle.

Slaves were employed in every form of skilled and unskilled labor. No tasks were performed solely by slaves, but they formed the overwhelming majority of workers in mining, manual and manufacturing work, entertainment, prostitution and domestic service in private households. Everyone who was not extremely poor had at least one slave.

Much like Greek citizens, the life of a slave could vary from decent to miserable. A decent life could be had if a slave worked in a home in town or in the country, where one might become almost a family member. Sometimes older male slaves accompanied their master’s sons to school and had the authority to discipline the boys if necessary.

Greek slaves had no legal rights and they sometimes endured abusive owners who beat them or forced them to have sex. On one hand, the Greeks were regarded as the most sophisticated and advanced people of ancient times, and are credited with moral, ethical and literary works, but on the other hand, we see examples like these which lead us to believe that they were not even aware of humanity.

Slaves were owned by the polis or by individuals. Those belonging to the polis had more status and more freedom, often living independently. They might be put to work, for example, working as policemen in Athens or cleaning up garbage, or they might be assigned to maintain the temple of the polis’s deity.

Female slaves were often found in households or working for a merchant in the agora. Educated slaves were valuable as tutors for children in upper-class homes. Slaves often worked alongside their owners on small farms in the countryside or at crafts such as pottery, sculpting, and metalworking. They might be as skilled as their owners at these crafts. Hoplite soldiers would have had little strength left for fighting if not for the slaves who carried much of their equipment from place to place.

Occasionally, slaves managed to improve their status. A few were able to earn money and save enough to buy their freedom. Some older slaves were freed by their masters as a reward for good service. The freed slaves were considered metics, which meant they could not vote and they needed special permission to own land. One rare case of a slave earning citizenship in Athens involved a man named Pasion (fourth century B.C.), who was freed and then managed the bank of his former owners.

The most miserable slaves in ancient Greece worked in the mines. Long days in the harsh conditions of the mine made for a short life. But in general Athens did not have the problem of slave rebellions that Sparta did with its helots. While helots were not technically slaves, they were still brutalized by the Spartans. The Athenians had fewer slaves than the Spartans did helots, and they did not treat their slaves as harshly as the Spartans did their helots. Without helots, Sparta might never have achieved its military strength. Without slaves, Athens may not have had enough silver to outfit its navy, which played such a key role in the city-state’s rise to an empire. 22

Manumission

Slaves could be freed (manumitted) by their masters. In Athens a simple declaration by the owner, before witnesses, was sufficient. Such freedom was often conditional, and freed slaves might be required to continue performing certain services for the former owner. Apart from giving other slaves some incentive, an owner often freed a slave toward the end of the slave’s useful life to avoid an asset becoming a liability which was the brutality of the Greeks towards those who spent their whole live in their services. What was the point of freeing a slave when he was about to die? On the contrary, Islam provided a better system to free slaves. Two ways have been proposed. Firstly, a master could free his slave by entering in to a contract with his slave. The contract would state that if the slave managed to earn a certain sum of money, he would be free. Secondly, the master could make an agreement with his slave that the slave would be set free upon the death of the master. Upon the death of the master, the slave would be set free and the children would not inherit him.

Freed slaves did not become completely free but were classed as freedmen or freedwomen. In Athens they had the same status as metics and had to register with a citizen (their former owner) as their patron and legal representative. The freeing of slaves was sometimes recorded in inscriptions, and such inscriptions are known from several places, including Athens and Delphi. 23 In some emergencies large-scale freeing of slaves took place in order for them to enlist or be conscripted into the army or navy because apart from helot revolts there is no record of slave revolts in Greek history, although many may have attempted to escape.

Metics

In city-states about one-third of free inhabitants could be noncitizens, including those foreign residents who had acquired the status of metics (metoikoi. metoikos, “one who dwells among”). A large and often prosperous metic population resided at Athens.

Though they enjoyed full civil rights, metics had no political rights and were not able to own land or houses in Attica or to legally marry citizens. They were obliged to pay an annual poll tax (metoikion) and property tax (eisphora) at a slightly higher rate than citizens. They undertook the normal duties of citizenship, such as naval and military service and liturgies, but had little chance of becoming full citizens. Most metics at Athens engaged in commercial and industrial activities, based largely at Piraeus. Some metics were physicians, philosophers, sophists, orators and poets. 24

Metics were found in most states except Sparta. In Athens, where they were most numerous, they occupied an intermediate position between visiting foreigners and citizens, having both privileges and duties. They were a recognized part of the community and specially protected by law, although subject to restrictions on marriage and property ownership. 25

These foreigners usually had to register their residence and so became a recognized class (lower in status than the full-citizens). In return for the benefits of ‘guest’ citizenship they had to provide a local sponsor, pay local taxes, sometimes pay additional taxes, contribute to the costs of minor festivals, and even participate in military campaigns when necessary. Despite the suspicions and prejudices against foreign ‘barbarians’ which often crop up in literary sources, there were cases when metoikoi did manage to become full citizens after a suitable display of loyalty and contribution to the good of the host state. They then received equal tax status and the right to own property and land. Their children too could also become citizens. However, some states, notably Sparta, at times actively discouraged immigration or periodically expelled xenoi. The relationship between foreigners and local citizens seems to have been a strained one, particularly in times of wars and economic hardship. 26

Men

In the Greco-Roman world, masculinity was defined in relation to its ostensible antithesis: namely, femininity. To be a “manly” man was not to be a woman, and in order to maintain that manliness, men had to avoid traits that were typically associated with women. Men, or at least “true” men, were characterized as being dominant, active, and self-controlled, whereas women were characterized as being subordinate, passive, and excessive, especially in terms of displaying emotion, loving luxury, and being overly concerned with their appearance. With these polarities of dominant/subordinate, active/passive, and self-controlled/excessive, the underlying assumption is that “man” is both the social superior and the unspoken norm. In other words, “man” is the type whereas “woman” is the antitype; “man” is the standard by which “woman”—or the “other”—is measured.

According to elite Greek authors, however, not all men were situated at the top of this vertical axis of power, for not all biologically marked males qualified as “true,” or “manly,” men. Simply having the necessary anatomical features did not guarantee that a specifically sexed man would have been considered a true man in the ancient world. Instead, true men were those of high social status who also embodied the requisite “manly” characteristics.

In the Greco-Roman world, the body was fundamentally portrayed in hierarchically gendered terms. Greek authors from Plato onwards positioned the head, soul, or mind as the most “elite” member of the body and sometimes as a separate entity altogether that rules over the inferior members of the body. The male body was the assumed norm and standard of perfection. Men’s bodies were characterized as hot, dry, and hard, whereas women’s bodies were characterized as cool, moist, and soft. The formation of these cool, clammy creatures is often attributed to a deficit of heat. With these polarities of hot/ cool, dry/moist, and hard/soft, the former terms characterize men and the latter characterize their defective counterpart, namely women. As Aristotle famously claimed, women were in effect “deformed” males.

At the most basic level, manly men wielded sexual power: namely, the power to penetrate others and to protect themselves from penetration by others. As “impenetrable penetrators,” manly men could penetrate either women or men, so long as they were the ones playing the active, insertive role. A man’s manliness was not dependent on the gender of his sexual partner (as it is often construed in modern times), but rather on his active role in the sexual act. There were of course limitations on whom men could penetrate, but these limitations were often linked more to status than gender. Elite males, for instance, could not penetrate other men’s wives or male citizens themselves, but could penetrate (in addition to their own wives) both male and female prostitutes and slaves. Indeed, elite males could molest their slaves and other noncitizens without legal recourse: While elite males were legally protected from such bodily violations, they lost this protection if they asserted their manhood sexually at the expense of another man.

Legally, the men had the right to acquire land and property, enter into business transactions, distribute dowries, and determine inheritance and property succession for his family. He legally held power over his household, including his wife, children, and slaves. Fathers also held sacral power as the priest of the family hearth, presiding over the worship of various household gods, as well as the father’s genius, or guardian spirit. In addition, Grecian authors often ascribed to fathers the power over life and death itself. Fathers had the power to beat and whip their slaves and even (according to some) to kill their children, either by exposing them at birth or by punishing them for disobedience. 27

Children

The most important event that could happen in the early Greek family was the birth of a son or daughter, and particularly of the former. In the case of the birth of a daughter a fillet of wool would be hung upon the outer door of the house to announce the fact; but if a son was born, the house door would be decked with the joyous wreath of olive branches to proclaim that an heir had come to inherit the ancestral possessions.

The little newcomer was given first a bath in tepid water and fine oil, and wrapped in swaddling clothes, then placed in a warm bed; for it was a baby of Athens. After the birth, the father would send someone to Sparta so that he could arrange one of those famous nurses prized for their success in raising children, but he remained afraid for bringing up the child according to Spartan customs without the warm swaddling, clothes. These clothes were soft woolen bands, three fingers wide, that swathed the whole body, even binding down the arms, so that only the head is visible. 28

Children of citizens attended schools where the curriculum covered reading, writing, and mathematics. After these basics were mastered, studies turned to literature (for example, Homer), poetry, and music (especially the lyre). Athletics was also an essential element in a young person’s education. At Sparta, boys as young as seven were grouped together under the stewardship of an older youth to be toughened up with hard physical training. In Athens, young adult citizens (aged 18-20) had to perform civil and military service and their education continued with lessons in politics, rhetoric, and culture. Girls too were educated in a similar manner to boys but with a greater emphasis on dancing, gymnastics, and musical accomplishment which could be shown off in musical competitions and at religious festivals and ceremonies. The ultimate goal of a girl’s education was to prepare her for her role in rearing a family. 29

To stimulate their thirst for self-improvement, adults allowed the young to observe their adult contests, of which there were many. Furthermore, young people themselves participated in contests appropriate for their age, where hopefully they would emulate some of the adult virtues, as history proved that, indeed, they did for quite a long time. For example, Marrou mentioned how young children would eat in a separate table, but allowed to observe adults perform their after-dinner oratory contests, which at the time were the standard intellectual staple that accompanied dinner. More importantly, since they heard so many adults compose original poems, they were also motivated to compose poems themselves, and become articulate and, erudite speakers. 30

Boys were taken from their mothers before the age of seven and trained in state schools until they were nine. From the age of ten to thirteen they were still undergoing state training and were made to go in for tests of endurance and skill. These contests were held in the Shrine of Artemis before an audience of friends and relations. The winner received as a prize nothing more precious than a steel sickle, which he had to dedicate to the goddess. Music entered also into these contests. But the most severe of all the tests which the children had to undergo was that of the ordeal by lash a test of endurance of a brutal and savage nature. 31

Too little is known of the material circumstances attending the mental and bodily training of girls, or at what age they were taught to read and write. Much, however in those ages was communicated orally. Their mothers imparted to them whatever notions they processed of religion, performed in their presence several sacrifices and other pious rites, and gradually prepared them for officiating in their turn at their country’s altars. 32

Women

Most women in most cultures except Islam have been discouraged from performing in the arenas of endeavor valued by their societies, and many have been either invited or compelled to confine themselves to domesticity. The women of ancient Greece were no exception; secluded, excluded, largely illiterate, they were never supposed to take a place in history. However, according to Islamic scholars, all the great teachers of mankind are indebted to a woman. In almost all cultures of the world, the women have been exploited simply because she was the weaker sex in respect of her physique. Physically she cannot be as strong as a male. This extremely superficial weakness of the woman has caused different cultures and civilizations to exploit the woman which has had tragic results. We find that even a man like Aristotle, who was considered to be the father of philosophy, had nothing rational to say about the woman. He said that woman was the freak of nature. It means that when nature failed to produce the real human being i.e. man, the result was woman. The same view was held by Plato, and some medieval and modern thinkers. However, in the view of Quran, both (men and women) are human beings of the same status. One should remember that Islam is the only religion which regards women as diamonds while other cultures regard women as pebbles and stones. 33

The following excerpts record some of the features of the reality of girls and women in ancient Greece, primarily in Athens but also in other places around the Mediterranean where Greeks had settled.

Childbirth

Probably because of the blood that issued with the newborn, the mother was considered ritually impure, both “polluted” and “polluting.” This could last for several days, as we learn from a sacred law from the Greek colony of Cyrene, in North Africa (4th century BC). It is found that the woman who had just given birth polluted the house; she polluted anyone inside the house, but she did not pollute anyone outside the house, unless he came inside. The person who was inside shall be polluted for three days, but he would not pollute anyone else, no matter where this person went.

Childhood

From birth to death a freeborn female in Athens was under the supervision of a ‘kyrios’34, the man who was responsible for her maintenance and upbringing as a child, and for all situations in which she would interact with the public, such as marriage or legal transactions. At birth, the girl child’s kyrios would be her father or, if he had died, her father’s brother or her paternal grandfather. At marriage, her husband became her kyrios. If she became widowed or divorced, she returned to her original kyrios if he was alive, or came under the kyreia of her son or the nearest male relative.

Married Life

A marriage was initiated by the kyrios of the future bride. He selected her future husband and contracted the betrothal with the pledge of a dowry (in all but the most impoverished families). Dowry, which is an amount of money, goods or possessions which are given to the bride by the bride's family at the time of her marriage so that they can get a good husband for her. After marriage, it became the property of the husband or his family.

When a young Athenian woman married, she was also expected to observe strict sexual fidelity to her husband. He would not be so constrained, however, and would have ready access to a variety of sexual partners, including the household slaves (male and female), adolescent boys and prostitutes (male and female).

Employment

Working at the loom, was an essential activity of women in the Greek world. Girls, wives and household slaves transformed raw wool by carding, spinning and weaving it into clothes and textiles for the household. Wool working also provided a source of income when this was required. The intricacy of weaving and the fact that women worked together at the loom led to its metaphorical association with storytelling but also with guile (comparable to the intricate fabric they produced).

Pregnant Women

For success in becoming pregnant and for safe delivery in childbirth, married women turned towards the gods. They might travel to a sanctuary of the god of healing, Asclepius 35 , for help with conception and birth.

Concubines

A concubine (pallake) was most likely a free woman without the status that would enable her to obtain a legal marriage, such as a foreigner (“metic”). She could still be in a common-law relationship with a man that was established by contract (whether formalized or not), parallel to a marriage sealed with a dowry and the appointment of a man as the woman’s kyrios (master).

Wife-Abuse

Because Athenian married men had ready access to a variety of sexual partners outside marriage without incurring the charge of adultery (unless they engaged in sexual activity with a married woman), wives were often passed over in favor of others. The behavior of Alcibiades 36 toward his (wealthy) wife Hipparete, the daughter of Hipponicus III, a wealthy Athenian was, like many of his other actions, notorious.

Hipparete, a well-behaved and affectionate wife, grieving over (Alcibiades) on account of his liaisons with courtesans – foreign and local – left the house and went to live with her brother. Alcibiades did not mind this, but lived shamelessly. So, she had to place her plea for divorce before the archon, and do it not through others but in person herself. When, therefore, she was out in public to do this in keeping with the law, Alcibiades came up to her and seized her and went bringing her home through the marketplace, with no one daring to confront him or take her away. She remained with him nonetheless until her death, and she died not long afterward when Alcibiades went and sailed to Ephesus. This violence did not appear to be at all outside the law or inhuman. For the barbaric law seems to have this purpose, that the woman who wants divorce goes ahead to the court in person, so that the husband may come upon her and get possession of her. 37

Prostitution

In the sixth century B.C. the Athenian lawgiver Solon institutionalized the distinction between good women and whores. He abolished all forms of self-sale and sale of children into slavery except one: the right of the male guardian to sell an unmarried woman who had lost her virginity. As part of his extensive legislation covering many aspects of Athenian life, Solon regulated the walks, the feasts, the mourning, the trousseaux, and the food and drink of citizen women. He is also said to have established state-owned brothels staffed by slaves, and thus to have made Athens attractive to foreigners who wanted to make money, including craftsmen, merchants, and prostitutes. 38 This kinds of mal-practices takes place when a man completely submits to his sexual desires, he then becomes more worried about his sexual needs rather than his productive life. Resultantly, productivity decreases, and the creativity in men ceases to function properly and the society moves towards decline. Hence the establishment of state-run brothels is akin to promoting immorality, and unproductivity in the whole society as can be seen in the civilization of ancient Greece.

We encounter two principal Greek words for a female “prostitute,” porne and hetaira. The former would apply to a slave working in a brothel or on the street, and the latter to a self-employed woman, but porne was also a rhetorical and derogative term applied widely, and both terms could be used interchangeably. 39 The term ‘whore’ or ‘porne’ referred to those women who occupied the lowest rank in the social position. In brothels, whores stood very lightly clad or even quite naked for show so that every visitor might make his choice according to his personal taste.

The ancient Greeks had female and male prostitutes who functioned at a full range of economic levels. At the bottom of the social/economic scale were the pornai (sing. Porne) common whores who either worked in the city streets or brothels (ergasteria).

According to authors of the late Classical period, brothel workers spent the day naked, flaunting their wares for passersby, either pulling men into the brothel or arranging themselves into a semicircle so that their buyer might better make his selection. Somewhere between the streetwalker and the brothel worker were those prostitutes who worked in oikemata (sing. oikema), “little houses,” or cribs. Male prostitutes, seldom associated with brothels, were commonly found here, if the words of the orator Aeschines are right: “You see these men who sit in the oikemata, who openly admit to practicing this profession. They are forced to it by necessity, but even they cover over their shame and close the doors.”

In the 6th century, evidence appears for a new type of prostitute in Greek society. Called variously singers, auletrides (flute players), psaltriai (harp players), and kitharistriai (lyre players), these were trained, professional musicians and entertainers who also happened to have sex with their clients. Male equivalents of these existed, and, to judge from the vase paintings, young male “wine servers” as well. As with many prostitutes of all levels, these prostitutes were often slaves, usually under the authority of a madam or pimp (pornoboskos, literally a “whore herder”), and their economic value was highly regarded. At the far end of the social/economic spectrum were the hetairai, literally “female companions.” There is continued debate as to what, exactly, is the difference between the hertaira and the pornê. Hetairai are generally understood to have been better educated than the pornai, thus intellectual as well as physical “companions.” A certain degree of economic autonomy was available to the hetairai, which was another important point of difference, as was the fact that, while pornai were hired for one “hop in the sack,” hetairai were hired for their company, including sex, sometimes even for long-term engagements. 40

Property

The surviving laws recorded in Athenian courtroom speeches indicate for the most part that an Athenian woman could not have property of any size. 41 Once married, her husband-kyrios managed her dowry. He could not sell any of this property or spend any of the funds transferred, but he could use this as, for example, security for a mortgage. If he did so, it would be indicated on one of the “mortgage stones” (horai) found throughout Attica. The amount would be returned to the wife’s family in the event of the death of the husband or divorce.

It was normal practice for the wife to retain the personal effects she had brought into the marriage as a bride. It was normal for the woman’s guardian (kyrios), if she were a widow or divorced, to arrange another marriage for her, in which case the dowry would be under the new husband’s control. Athenian women could conduct commercial transactions, but the size of this was limited by law, as we learn from several sources, such as the following:

The law explicitly forbids permitting a child or woman to perform a transaction more than (the value of) a medimnus of barley. (A medimnus of barley was roughly equivalent to three bushels. The value of this amount of barley has been calculated as the price of feeding an average family for approximately one week.)

Women who felt that they had been victims of the mishandling of property within the family could not sue for justice in their own name, but would need to find a supportive male relative to issue a court challenge. One such woman was the widow of a wealthy Athenian merchant Diodotus, who had been killed in battle. Not a woman easily intimidated, she accused her father Diogeiton, the brother of her deceased husband, of cheating her sons in the distribution of Diodotus’ estate, and using the funds due to them as inheritance for enriching his family by his second wife. Her son-in-law represented her in court, reporting that she had sought his help in summoning her father before other male relatives. He tells the jury that she had then asked her father how he could treat his nephew in this way.

‘With you being their father’s brother and my father, their uncle and grandfather Even if you aren’t ashamed in the face of any man, you ought to fear the gods – you who took the five talents my husband left behind as a deposit when he sailed away to war. I am willing to swear the truth of this, on the lives of my sons and the children born later to me, in any place that you name. I am not so desperate, nor do I put such store in money as to end my life having perjured that of my own children, nor would I wish unjustly to steal my father’s property.’

Because there were no official records kept of marriages, a woman who needed to prove that she had been legitimately married (for example, for public acknowledgement of the legitimacy of her children, or to establish lawful inheritance for them and for herself when her husband died) had to have recourse to other means. These could include an appeal to the eye witnesses at her marriage party, the acknowledgement of her sons by her husband’s tribe (phratry), or her own participation in a religious festival such as the Thesmophoria, which was open to lawfully wedded women whose husbands belonged to a citizen group (deme). One such attempt to assert legitimacy is made by a woman who is attempting to lay her claim to the estate of her deceased father, Ciron. Her son conducts the suit in court. 42

Heiress

In families in which a son was lacking, the daughters were responsible for perpetuating the oikos. In such a family the daughter was regarded as “attached to the family property”; hence she was named epikleros. The family property went with her to her husband, and thence to their child. This arrangement shows that although males were preferred to females, succession at Athens was not strictly agnatic in the sense that only males were legally able to inherit, although the epikleros never truly owned her father’s property. It was the duty or privilege of the nearest male kinsman to marry the heiress. The order of succession to the hand of the heiress was the same order in which the male kinsmen would have succeeded to the father’s estate if there had not been any heiress at all, i.e., brothers of the deceased, then sons of brothers of the deceased; there is some ambiguity as to whether the estate–and the hand of the heiress–then went to sons of the sisters of the deceased or to grandsons of brothers of the deceased. The disparity in the ages of the resulting married couple was not a factor, as long as they were capable of reproduction. 43

Elderly Women

Women, after the age of childbearing are almost invisible in the historical record of the Classical period. Nonetheless, some priesthoods were reserved for older women, including the highly influential Pythia, who channeled the voice of Apollo at Delphi. Diodorus (1st century B.C.) gives us an account of the reasons why she was chosen from this sector of the population.

It is said that in former times virgins gave out the oracles because of the incorruptibility of their nature and because of their resemblance to Artemis. For they are well suited to guarding closely the secrecy of the revelations of the oracles. In more recent times, however, they say that Echecrates the Thessalian, when he was present at the oracle and caught sight of the virgin delivering the prophecies, lusted after her because of her beauty and abducted and raped her. The Delphians, because of the disastrous occurrence passed a decree that in the future no longer would it be a virgin who gave the oracles but a woman older than 50 years of age who would do the prophesying. She dressed in the clothing of a maiden, as a reminder of the prophetess of olden times.

Older women doubtless acted as helpers and attendants within the family. They did not always enjoy respect. Some literary texts reflect a stereotyping of them as hags desperate for drink and sex. (One might recall that many women were widowed young, the result of their being married to men much older than they and the fact that many men died prematurely on the battlefield.) 44

Food

Food was undoubtedly the most important aspect of people’s lives, and many poor people were likely to never have enough to eat. Little work has yet been done on excavated skeletons from ancient Greece to assess malnutrition. There were few taboos on what was eaten. Diet and dining customs depended on the standard of living and geographical region—Spartan food was said to be the worst in all of Greece. The diet of most people was frugal, based on cereals (grain), olive oil and wine, with possibly legumes an important element as well, with little else to add to the variety. Cereals, mainly barley and wheat, provided the staple food. Originally husked barley was predominant (ground to make a paste, bread or a gruel), but later species of wheat were cultivated and made into bread.

The times of day when meals were taken and the names of the meals themselves varied at different periods. In early Greece breakfast (ariston) was eaten soon after sunrise. There was a main meal (deipnon) in the middle of the day and a supper (dorpon) in the evening. In Athens in the classical period only two meals were eaten—a light lunch (ariston) and a dinner (deipnon) in evening, but from the 4th century B.C. breakfast (akratisma) was again added to the daily meals. For most people meals were relatively simple, with little difference between the town and the countryside. Breakfast and lunch were light meals and may frequently have been eaten outdoors, whereas the main meal was usually eaten indoors. People ate their food with their fingers, no doubt assisted by bread, and those that could afford it had slaves standing by to wash their hands when necessary. Men and women would have eaten separately in many households.

Reclining on couches to eat was introduced from the Near East toward the end of the 7th century BC for special occasions such as the symposium, and special dining rooms often held 11 couches, set against the wall, each with a small table alongside. 45

Most Greeks ate simply. Bread was the main part of every meal. In general, there were two types of bread available at the market: maza was made from roasted barley meal kneaded with honey and water or oil and cooked over heat; artos was a round wheat loaf baked in an oven. Maza was less expensive and so was more common among poorer residents.

Everything else accompanying the bread was referred to as opson, whether it was vegetables, olives, eggs, or meat. Vegetables were more expensive than lentils, so lentils were another staple food for the poor. Lentil soup made an inexpensive but filling meal. A typical Athenian breakfast (one of perhaps two daily meals) was maza or artos soaked in diluted wine with a few olives or figs. (Wine diluted with water was a regular part of the Athenian diet.)

Meat was usually eaten only at festivals, after a sacrifice. Greeks ate perhaps four pounds of red meat per person each year, plus snails, fish, and birds. People who lived in the country had more meat in their diet, while city dwellers ate more fish, imported from the Black Sea. A favorite dish among the Spartans was a broth that included wine, animal blood, and vinegar. 46

Beverages

Wine was the most common drink, generally watered down and artificially sweetened. Some wine was spiced and flavored, and some was heated to make a warming drink. Drinking undiluted wine was considered barbaric. The best wines were the most expensive, and wines drunk by the poor were of the lowest quality. Drinking beer and milk was also regarded as barbaric. Milk, usually from sheep or goats, was reserved for making cheese and for medicinal purposes. There were no infused drinks like tea and coffee, nor any distilled liquors. 47

Due to the societal drawbacks, and negative effects on health, the intake of any sort of Alcoholic beverages should be avoided (except in few life-threatening situations). A common individual may understand the drawbacks of its intake. When any person takes alcoholic drink, he is unable to maintain the balance of his body, thoughts and actions in the same as he behaves in normal. If he drinks more, his brain ceases to function properly, and he forgets morality, forgets society, and the person does not know what he is doing. Many cases have been reported in which a drunken guy either killed his wife, or someone else, raped his daughter or even his mother, and ran around the street naked, etc.

As for health issues, one should know that drinking can cause blackouts, memory loss and anxiety. Long-term drinking can result in permanent brain damage, serious mental health problems and alcoholism. Secondly, drinking alcohol is the second biggest risk factor for cancers of the mouth and throat (smoking is the biggest). People who develop cirrhosis of the liver (often caused by too much alcohol) can have liver cancer. The list is extensive, but here these details will suffice.

Housing

The architecture of the Greek house varied considerably over time, from the one and two room houses of the Early Iron Age to the spacious, almost palatial residences of the Hellenistic period. Domestic architecture, including both the materials used in construction and the organization of space, provide valuable information about the people who built and lived in a house. Paths of access from one part of a house to another, reveal how the builders and inhabitants of a home regarded concepts such as privacy and also represent strategies for social control, as restricted access to any given space might represent a desire to limit entrance to such rooms. The construction techniques and materials not only reflect age old practices of building and locally available stone, wood, and soil, but are at times manifestations of culturally constructed ideas of taste, wealth, and power. More expensive and consciously placed features of interior decoration, such as painted plaster walls, mosaic floors, and freestanding sculpture, further express the status and aspirations of the home owner.

The house was not simply a free-standing entity that was devoid of meaning beyond its stones, wood, mud brick, and terracotta. Beyond these, the architectural layout and its details speak to the social life of the inhabitants, both how ideas of social interaction lay behind the construction of the domestic environment and how that environment itself regulates the behavior of those living within the confines of the house.

In the city of Athens, which may be taken as typical, the private houses were mostly of only one storey, but there must have been many blocks of dwellings of three or four storeys to accommodate the poorer classes, slaves, etc. 48

A constant feature in most Greek houses from the Late Archaic period onward was a central courtyard enclosed within the walls of the house, providing light, air, and access to the surrounding rooms; however, the one architectural feature of houses most discussed in the past, but mostly absent in the reality of the remains, is a distinct women’s quarter. In the fifth century B.C. the increasingly common residential plan was built with an entrance vestibule, a feature that controlled both physical and visual access to the interior of the house.

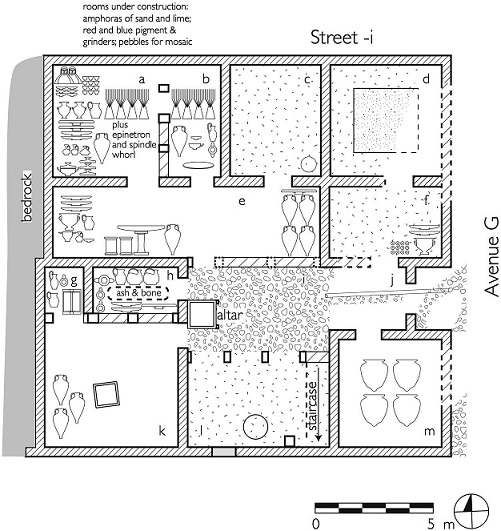

The floor plan of a house in ancient Greece may be seen in the figure below.

Figure 1 Olynthos, House of Many Colors, plan. 49

Women Clothing in Athens

Minoan clothing for women consisted of flowing floor length dresses, some of which had flounces. Some women are portrayed naked above the waist, while others have a tight-fitting bodice leaving the breasts bare, and there was a belt at the waist. A variety of hats or headdresses seem to have been worn, often rising well above the top of the head. In Mycenaean representations women are often shown in a similar long flounced skirt, with a tight bodice apparently worn over a blouse. In both Minoan and Mycenaean representations this type of dress is highly decorated. Mycenaean women were also portrayed wearing a long, ankle length

Minoan clothing for women consisted of flowing floor length dresses, some of which had flounces. Some women are portrayed naked above the waist, while others have a tight-fitting bodice leaving the breasts bare, and there was a belt at the waist. A variety of hats or headdresses seem to have been worn, often rising well above the top of the head. In Mycenaean representations women are often shown in a similar long flounced skirt, with a tight bodice apparently worn over a blouse. In both Minoan and Mycenaean representations this type of dress is highly decorated. Mycenaean women were also portrayed wearing a long, ankle length tunic with short sleeves and a girdle at the waist. There was one portrayal of a fringed shawl, but otherwise little is known about outer garments such as cloaks.

In the Archaic period the normal female dress seems to have been the peplos. It was made from a rectangle of woolen cloth, taller than the woman wearing it and more than twice her width. The top of the rectangle was folded over outward, so that the cloth was of double thickness above the waist. The cloth was then wrapped around the body, and a piece of the cloth (epomis) was pulled over each shoulder and fastened in front with pins. The garment was held secure and supported by a girdle at the waist. Some examples of peplos had the open side of the garment sewn up, but mostly they overlapped and were held in place by the girdle. These dresses are often depicted as richly decorated. A linen cloak or shawl could be worn over the peplos, in later times called a himation.

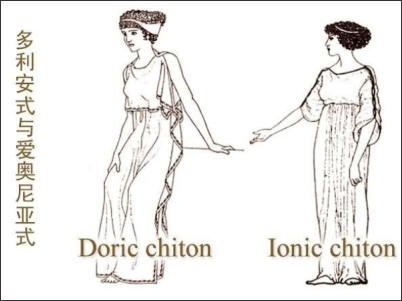

In the Classical period there was a change from the peplos to the chiton (khiton), which was a wide tunic worn by both men and women. The various forms of chitons included the Ionic chiton, made from a rectangle of cloth, with two edges sewn together to form a tube. It was a sleeved garment, closed across the shoulders and upper arms by buttons or several small brooches. The excess length was pulled up and held by a girdle at the waist to form a kind of pouch called a kolpos. Sometimes it was also held in place by cross cords running from the shoulders to the waist. The Archaic peplos was not immediately superseded, and was sometimes worn over the chiton. It continued to be worn in the Peloponnese into the 5th century B.C. The peplos developed a large overfold at the waist, and this developed garment was now called the Doric chiton. Eventually the two styles of Ionic and Doric chiton began to be mixed, and sometimes both types were worn at once, one over the other.

Outside the house women always wore a wrap or cloak called a himation, apparently a generic term for such garments. There were variations in size, style and the way they were worn. For example, the khlanis was a wrap of very fine wool, the most famous of which came from Miletus (khlanis Milesia). The xystis was a long robe of fine material for special occasions, and the ephestris was of thicker wool.In Hellenistic times the dress of the Classical period continued to be worn, but there was increasing variety in the combinations of the various garments and the ways in which they were worn. 50

Women Clothing in Sparta

In Laconia the Lacedaemonian or Spartan women observed fashions quite different from all their neighbors; their virgins went abroad bare-faced, the married women were covered with veils; the former designing to get themselves husbands, whereas the latter aimed at nothing more than keeping those they already had.

Lycurgus, the Spartan lawgiver, seems to have encouraged a fashion in the younger women of wearing exceeding scanty costume, and even accustomed the virgins to dance and sing unclothed in the presence of young men at national festivals.

By wearing the scanty garment, or none at all, the Spartan girls had freedom in the exercises of running, wrestling, and throwing quoits and darts. The skirts which the virgins wore were not sewed to the bottom, but opened at the sides as they walked, and discovered the thigh.

The young women wore only a woolen robe, loose at one side, and fastened by clasps over the shoulder. Embroidery, gold, and precious stones were thought too despicable for the adornment of noble and respectable women, but were only used by courtesans, in the best period of the Spartan fame. Later, however, when Sparta gained immense quantities of gold and silver after the Peloponnesian war, and the laws of Lycurgus were neglected, the Spartans showed themselves as weakly fond of luxury as their neighbors. The women, too, lost much of their noble simplicity, and with it the serene womanly modesty for which they had been distinguished. They made such evil use of the freedom the laws of Lycurgus had given them, that they got a bad name on account of their wantonness and excessive desire for pleasure. 51

It is one of the common practices that people hide their ‘precious’ things and show their invaluable belongings. For example, if a person has a diamond, he will hide it in the securest safe, and won’t let anyone to come near it. On the contrary, if that person has some pebbles, or ordinary stones, he will never hide or even carry it. The same is the case with woman; Islam gives woman a dignified position. She is like a diamond, and hence needs to be covered. If she wears scanty clothes, she is vulnerable, looked upon with lusty eyes and loses her respect.

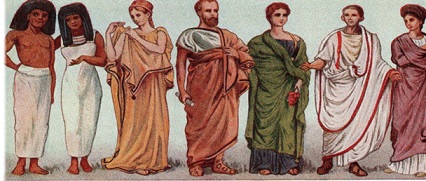

Men’s Attire

The earliest Minoan depictions show men wearing only a belt and codpiece, possibly made from soft leather. Later they are shown with one of the two types of dresses that have been called the kilt and the apron, both supported by a decorated belt. The kilt was a skirt reaching to the thighs at the back, and to the knees in the front, often ending in a long tassel. There were two forms of apron. The double apron reached the thighs at the back and front, and was cut away at the sides. It was often worn with a codpiece. The single apron was the back half of the double apron and was worn with a codpiece. Like female Minoan dress, kilts and aprons could be lavishly decorated. In Mycenaean artistic representations, men are generally shown wearing a tunic reaching to the thighs, with short sleeves and a belt or girdle at the waist. Men are also shown in a short-flared kilt or in what appears to be shorts decorated with rows of tassels or fringes.

In the Archaic period men wore the Ionic tunic (chiton), which appears to have been sewn rather than pinned. Older men, and wealthy younger men, usually wore an ankle-length chiton without a girdle, while younger men and those involved in activities wore a thigh-length chiton. The garment was often made of linen, but woolen versions were warmer and cheaper. A wrap or cloak could be worn over the chiton, and occasionally the cloak was the only garment that was worn. Khlaina (in later Greek, himation) referred to various types of cloaks or wraps. Male craftsmen and laborers were often depicted wearing a loincloth or short kilt (zoma), possibly also worn as underclothes.

Men’s dress in the Classical period was even more like women’s dress than previously. The various types of Ionic chitons continued to be worn, and there was a male version of the Doric chiton. This was a shorter tunic without an overfold that reached only to the thighs or the knees and was pinned at the shoulders. The exomis (“off the shoulder”), a variation on the Doric chiton, was only pinned at the left shoulder, leaving the right shoulder and breast bare.

Various cloaks and wraps were also worn over tunics or as the sole garment. The generic term himation is used for these garments, although different types can be distinguished. The himation was usually a large piece of cloth wrapped around the body and over one or both shoulders.

The tribon was a cloak of coarse, dark-colored wool; it was worn on its own and was the traditional dress of the men of Sparta.

The chlamys (khlamys) cloak was usually worn over the left shoulder and fastened over the right shoulder with a pin or brooch, leaving much of the right side uncovered. It could also be fastened at the throat, allowing both shoulders to be covered. The chlaina (khlaina) was a thick winter woolen cloak. In the countryside peasants often wore garments made of animal skins, such as the diphthera and spolas (goatskin or leather jerkins), and a goatskin or sheepskin cloak called a sisyra or haite, which was cured with the hair or wool left on. In Hellenistic times men’s tunics were usually sewn rather than pinned, and generally had long or short sleeves rather than being sleeveless. The draped himation was often the only garment worn.

Shoes

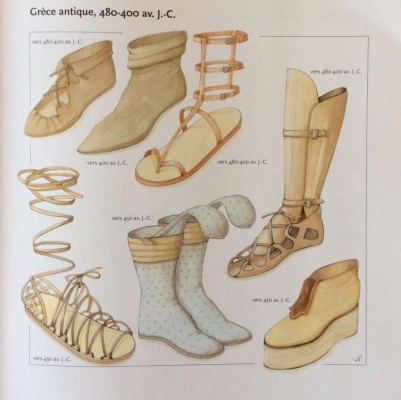

Indoors, and often outdoors, many people went barefoot much of the time, but a variety of footwear was also in use, including sandals, shoes and boots. Shoes were made from cattle hides, or finer shoes from skins of sheep, goats and calves. Felt was used in the production of warm boots, and soles were sometimes made of wood. Kroupezai were high shoes made of wood, some worn by flute players to beat time and some worn for treading olives. Various types of sandals (called sandalia and pedila) consisted mainly of a sole strapped to the foot, sometimes with thongs carried a short way up the leg. Shoes or short boots (hypodemata koila) were similar to sandals but enclosed the whole foot. They ranged from light, loose-fitting shoes that were almost like slippers to heavy-duty nail-studded types. 52

Public Bathing

The history of public baths began in Greece in the sixth century B.C., where men and women washed in basins near places of exercise, physical and intellectual discussions. Later gymnasia had indoor basins set overhead, the open maws of marble lions offering showers, and circular pools with tiers of steps for lounging.

As early as Homeric times it was generally the custom to swim and bathe in the sea or rivers; yet even then the luxury of warm baths-for these were regarded as a luxury by nearly the whole of Greece-was quite common. Similarly, it was a matter of course for a warm bath to be the first thing prepared for a guest after he alighted. In the bath he was attended to by one or more girls, who poured lukewarm water over him and anointed him with oil; that is, they massaged him vigorously with hands moistened with oil in order to make his skin supple. 53

Social Gatherings

Dance, according to Greek thought, was one of the civilizing activities, like wine-making and music. The strong dancing tradition prevalent among the Greeks was likely inherited from Crete which was conquered by Greece around 1500 B.C. but Greece was very active in stealing the better from surrounding cultures, its poets and artists plagiarized significantly from surrounding Pyria and Thrace and its scholars were being initiated into the Egyptian mysteries by temple priests long before Alexander the Great conquered Egypt. Learning to dance was considered a necessary part of their civilization and education which favored in learning was considered the appreciative ones among them.

The art of mousike included poetry, dancing and music. Dancing was a popular form of entertainment from at least the time of Homer, taking place at weddings, funerals, harvests and religious occasions. Public religious festivals were accompanied by music and dancing, with simple rhythmical movements performed by a chorus (khoros, dance). The word khoros can mean chorus, dance or dancing-ground. By Archaic times the male chorus sang as well as danced in performances of choral lyric poetry, usually under the direction of a leader. 54

Professional dancers (usually slaves and prostitutes) often entertained at dinner parties. More than 200 names of dances have survived, including particular dances in tragedy and comedy, such as a lewd kordax in comedy and a stately emmeleia in tragedy. 55 Some of them are as follows:

Geronos or chain dance:Sexes did not mix during dance except for the chain or Geronos dance. Grown up men and women did not generally dance together, but the youth of both sexes joined in.

Gymnastic:Among the gymnastic, the most important were military dances. It was of Phrygian origin and of a mixed religious, military, and mimetic character.

Pyrrihic or Korybantes:The dance in armor (the "pyrrhic dance" or pyrriche) was a male coming-of-age, initiation ritual linked to a warrior victory celebration. Plato describes it as representing by rapid movements of the body, the way in which missiles and blows from weapons were avoided, and also the mode in which the enemy were attacked.

Sikinnis:both a dance and a form of satirical mimo-drama. It burlesqued the politics, philosophy and drama of the day and was said to cater to the taste of the common people for vulgarity and sensationalism. 56

Symposia

The Greek word – symposion – literally meant ‘drinking together’. The roots of the institution lie in the archaic period, the eighth to sixth centuries B.C. In practice it must have taken many different forms in different contexts and locations, but there are recurring features. The symposium was a drinking party, held most often in private homes. It was a venue for elite, male sociability, sometimes even viewed as a politically subversive, anti-democratic space. The only women present would standardly have been courtesans (hetairai). It had established rules and elements of ritual: drinking usually followed a meal (deipnon), and was preceded by libations (offerings of wine to the gods), and led by a ‘symposiarch’ (leader of the symposium), chosen by the other guests, and responsible for supervising the mixture of wine with water and controlling the pace of drinking.The symposium was often represented as a typically civilized, Hellenic institution in contrast with the customs of barbarians who did not mix their wine with water. It was also often represented as a place for education of young men into their duties as citizens, sometimes also as a place for homosexual courtship of young men by older men. The physical space of the Greek dining room (andrˆon – literally ‘room for men’), as we know from its many surviving examples, was an intimate, inward-looking space. Standardly it consisted of either seven or eleven couches, each one long enough to hold two people reclining, arranged around three and a half sides of a square, leaving room for servants to enter on the fourth side.

The symposium was also a venue for musical entertainment provided by outside entertainers. Even more important, however, was the entertainment provided by the guests themselves, through singing and conversation. Sympotic talk and sympotic song, as they are represented in the literature of archaic and classical Greece, were thought of as shared, community forming activities. 57

Marriage

The first step towards the wedding ceremony was a separate ritual in its own right, the betrothal. Marriages were often arranged for political reasons, and two wealthy and powerful families would share a very strong and influential bond once joined by the marriage of a daughter and a son. Some scholars believe that marriage among the Athenian upper classes was highly endogamic, and that this provided a way for a father to keep his wealth in his own family while marrying off his daughter. Sometimes a family with few political ties and little wealth would have great difficulty in betrothing a daughter, in such case they may turn to a matchmaker for assistance.

The betrothal ritual was a relatively informal ceremony performed by the legal guardian of the prospective bride and the groom or his legal guardian. A girl had no legal power in the arrangement of her marriage, and the formalities which sealed her fate occurred in her absence. In fact, the engye 58 could have taken place quite a few years before the marriage, even while the bride was very young and had not yet reached menarche. This disregard for the bride’s consent in her own betrothal is indicative of a very important facet of womanhood in Classical Athens: male guardianship. Women in Athens were always maintained under the protection of a kyrios, first their father, then their husband, then their sons. In the absence of all of these figures, a woman would remain under the control of a close male relative. This engye ceremony would typically have been accompanied by the transfer of a dowry from the girl’s legal guardian to her future husband. The dowry was usually composed of a combination of things: land, money and goods, including slaves and servants.