Lifestyle of Ancient India | Society, Caste and Culture

Published on: 05-Oct-2024(Cite: Hamdani, Mufti Shah Rafi Uddin & Khan, Dr. (Mufti) Imran. (2020), Lifestyle of Ancient India, Encyclopedia of Muhammad  , Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 783-803.)

, Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 783-803.)

The civilization of ancient India was one of the oldest civilizations of the world. In this part of the world, there existed a caste system which ensured luxury, authority and complete superiority of a single caste over the rest. Some scholars believe that the ancient Indians were an intellectually developed nation. This claim seems far-fetched after taking a general view of the society and its value systems.

India was home to one of the world’s earliest civilizations. The people of this culture raised crops and livestock in the fertile plains of the Indus and Sarasvati rivers. They created beautiful pottery, jewelry, stone and metal sculptures. They built splendid walled cities, including Harappa and Mohenjo Daro. Archaeologists exploring the Indus Valley cities have uncovered the ruins of paved streets, massive brick buildings, and a sophisticated system of baths, toilets, and sewers. They have also found clay seals carved with an ancient form of writing that has never been deciphered. 1

In ancient India, not only was there tremendous development of mathematics, astronomy, medicine, grammar, philosophy, literature, etc. but there was also tremendous development of law. This is evident from the large number of legal treatises written in ancient India (all in Sanskrit). Only a very small fraction of this total legal literature survived the ravages of time, but even what has survived is very large. 2 However, despite such developments, their society was plagued with the barbaric caste system and was never able to unite or prosper.

Hindus were famous from antiquity for their asceticism. Ascetic practices (Tapas) were assumed to create powers that were irresistible. Self-control and observation of a strict regimen were part of general ethics. A Hindu was expected to become more and more detached from self-indulgence as he progressed through life. A Brahmin’s life was to end in Samnyasa, total renunciation. Those who had renounced enjoyed high social status. Apart from reducing one’s wants to a minimum and practicing sexual continence (Brahmacarya), samnyasis developed a great variety of forms of tapas, ranging from different forms of abstention from food and drink and other sense gratifications, to lying on a bed of nails, standing for prolonged periods in water, looking into the sun, lifting an arm up till it withered. One of the more widespread forms of self- mortification was the ‘Five-fires-practice’ (pancagni tapas): the ascetic sat in the center of a square which was formed by four blazing fires, with the sun overhead as the fifth fire. Renunciation was held to be the precondition for higher spiritual development, and the practice of asceticism in one form or other was expected of every Hindu. 3

Population

No definite figure can be suggested for the population of ancient India. Perhaps because the people in those days did not attach much importance to this question, the samskrta and pali literatures give us no information on the point. For the purpose of revenue collection, however, lists of estates were kept in the record department. The size of an estate (grama) was governed by the possession of kula (the family of a samanta)/ hypothetically each samnta-kulla was considered to be the owner of an estate (grama) which contained pasture, fallow and cropped land. It is rather interesting that the same word kula was used to denote and area of land which could be ploughed by two yokes of exen; the seed sufficient for sowing this area was called kulya; and a person belonging to a samanta-kula was expressed by the word kulina, meaning “nobleman”, and a lady by the word kula-duhitr, etc.

It has been calculated roughly that ancient India consisted of 7,000,000 gramas (estates), and that each grama represented from fifteen to twenty persons. Multiplying 7,000,000 by fifteen and twenty, we would arrive at a total population for ancient India of between 105,000,000 and 140,000,000.

According to the Buddhist books, vaisali contained 77707 rajans (estate-owners). Taking from fifteen to twenty persons for each estate, the population of the whole of India would come to between 100 and 130 million. The total population of vaisalijanapada is given in Buddhist books as 168,000. Multiplying this by 840 we get the population of India as 141,120,000, or in round numbers 140 million. The janapada of vaisali, owing to its fertility, was probably more thickly populated than many other janapadas. 4

Calendar

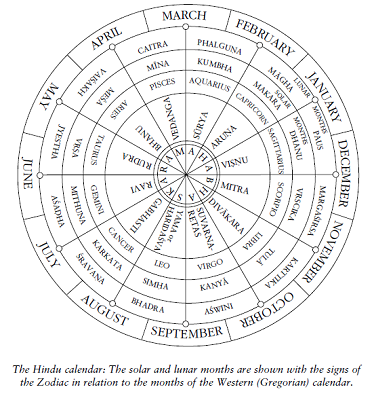

Hinduism based its reckoning of time on a lunar calendar. Dates of holidays and festivals thus kept changing from year to year. The Indian lunar year consisted of 12 months, with an intercalary month inserted once every 3 years or so, which helped the Hindu calendar approximate solar dating standards. A lunar month lasted from one new moon to the next, and was named according to the Indian month in which it began. Therefore, the lunar month known as Bhadra, for example, began with the first new moon after August 16th, for instance, and continued from there. Though the exact procedure of calculating such dates was somewhat complex, Hindus engaged experienced astrologers and astronomers whose special task was to assess the auspicious time periods associated with a given festival, and their calendars were prepared for them.

All Hindu calendars originated from the Jyotish Vedanga, though time sequence techniques and additional methods of calculation were added later, usually at the behest of astronomers and those accomplished in related sciences. In other words, months were calculated according to the sun’s position against fixed stars, or constellations, during sunrise. The sun’s position was understood by diametrically opposed observations of the full moon. This abrogated the need for leap year adjustments, but the number of days in any given month varied by nearly 48 hours, and conversion of dates to Gregorian or day-of-the-week computations requires the use of an ephemeris. The average person therefore relied on the panchangs, or almanacs, produced by authoritative Hindu astronomers. 5 The calendar is given below: 6

Social Classes

The main feature of ancient Indian society were the castes. This referred to the division of society into many groups which lived side by side, but often do not seem to live together. 7 Caste was the Hindu form of social organization. No man could be called a Hindu if he was not associated with caste. 8

Rama Shankar Tripathi states that there were four classes of people, Ksatriyas, Brahmanas, Vaisyas and Sudras. The Ksatriyas who were given preference over the brahmanas occupied the first place. They represented the ruling class, claiming the Aryan descent. The members of a royal family passed as Ksatriyas. They were warriors by training and occupation. Though they were warriors, the recruits to the military regiment of a kingdom were not necessarily all Ksatriyas, then came the Brahmins in point of superiority who were proud of their caste. There were five kinds of brahmanas as mentioned in the Buddhist text: Those who lived in the northern or north–western country, those who lived at Benares, those who lived in Magdha and Rajagrha, those of Bharadvajagotra, and the Kanhayana-Brahmanas. The Brahmins in those days followed the pursuits of agriculturists, craftsmen, tradesmen, landlords, order-carriers, sacrificers, etc. The Mahasala Brahmins were those who were men of substance. The Brahmins claimed two privileges, un-molestibility and immunity from execution. They were not required to pay rents so far as the land endowments were concerned.

The Vaisyas (Vessas) formed the third grade of the indo-Aryan Society with trade and commerce, agriculture and farming, as their distinctive occupations. The Sudras came next to the vessas (Vaisyas). They were known in the Buddhist age as slaves as opposed to free men. They were employed as domestic servants in the houses of the rich. 9 According to Rigveda, the sudras were created from the feet of the cosmic being Purusha while the other three castes were created from the mouth, arms and thighs. 10 The Sudras were no doubt recognized as a distinct order of society in later Vedic literature, but they were regarded as impure and not fit in any way to take part in sacrifices, or recite the sacred texts. Aryan marriages or illicit relations with sudras were severely condemned. They were also perhaps not allowed to possess property in their own right. Indeed, the Aitareya Brahmana at one place represents the Sudra as the servant of another, to be expelled at will, and to be slain at will. 11 Besides these four classes there were some low castes such as candalas, pukkusas, VenasNesadas, Rathakaras, Potters, Weavers, Leather-workers, mat-makers, etc. 12 However, according to the popular belief, the Brahmin caste was at the top.

Family

The ancient Indian family was an extended one which meant that a close link was maintained between brothers, uncles, cousins, and nephews, who often lived under one roof and who owned the immoveable property of the family in common. It was patriarchal and patrilineal. The father was the head of the house and administrator of the joint property and the headship descended from the male line. It was always the family rather than the individual that was looked on as the unit of the social system. 13

Women

Various etymologies were given to the various synonyms of ‘women’ in Prakrit. She was called ‘nari’ because there was no worse enemy of man than her; she was termed ‘mahila’ because she charmed by her wiles and graces; she was called ‘mahiliya’ because she created great dissension, she was called ‘rama’ because she took delight in men by means of her coquettish gestures; she was called ‘angana’ because she loved the body of men, she was called ‘lalana’ because she attracted a man even in domestic quarrels, and kept company in pleasures and pains; she was called ‘josiya’ because by her tricks and devices she kept men under subjugation; she was called ‘vanita’ because she catered to the taste of man with various blandishments. 14 Such was the low-mindedness of the ancient pseudo intellectuals.

Social correlates of gender, such as caste, class, stage of life, age, and family membership, were all variables that significantly affected the position of women in ancient Indian society, so that women in Hinduism demonstrated significant differences in their lives. It was the case that in prehistory everywhere there were significantly more autonomy and sexual freedom for women (and men) than in later times. In pre-Vedic times in India (before 1500 B.C.), such freedom and autonomy existed among the pre-Aryan tribal people who inhabited every corner of India. Tribal groups such as the Santals did not restrict women’s sexuality and action in any way as their staider counterparts in the larger culture did. 15

In Vedic times, women and men were equal in almost every respect: they shared rituals and sacrifices, learning and honors. Some sacrifices, such as the harvest sacrifice (sita) and the sacrifice to secure good husbands for their daughters (rudrayga), could only be performed by women. Women chanted the Samansand, composed many of the hymns of the Rig-Veda. There was a provision for change in gender (uha) in many ritual formulae to alternately have a woman or a man perform the ritual. They were also teachers of Vedic lore, and girls were given the same education as boys. The epics and Puranas, while extolling some women such as Sita and Draupadï, generally exhibited a negative attitude towards women: they described them as vicious, sensual, fickle, untrustworthy and impure. Women’s only sacrament was marriage and only through service to their husbands, regardless of their behavior, could they hope to find salvation. A faithful woman (sati) was supposed to accompany her husband on the funeral pyre. Childless widows could expect a grim fate: they could not remarry, and were almost without any rights. 16

Many professions were open to women such as weaving, embroidery, cane-splitting, dyeing, etc. Daughters shared in the household work; they brought home water from wells, jars beautifully poised on their heads and otherwise helped mothers in the housework. 17 They were also employed in the preservation and expenditure of wealth, in purification and domestic duties, in the cooking of daily food, and in the management of household property and furniture. 18

In the dharma literature, women from all social groups were considered at the same ritual level as shudras—they could not undergo a second birth, were forbidden to hear the Vedas, and were forbidden to perform certain religious rites. At the same time, women played an immensely important part in Hindu religious life, as daughters, mothers, wives, and patrons. According to the traditional dharma literature women had their own special role to play, based on their status as women. 19 Women could not inherit or own property; and their earnings as well, if any, accrued to their fathers or husbands. The birth of a daughter was considered ‘a source of misery’. 20

The women were thought to be faithless, ungrateful, treacherous, untrustworthy and strict control needed to be kept over them. It is said that a village or a town in which women were strong was sure to come to grief. 21 Women were believed to be sinful, having no natural inclination to dharma, hence they needed to be continually goaded and reminded of their duties, and so remained perpetually dependent. As stated by the renowned lawgiver, Manu: in her progression through life, a woman needed to be under the authority of some male person: first father, then husband, and finally, in old age, son. 22

Adultery was much more serious for women. An adulterous woman needed toperform a rigorous penance until her next menstrual period—sleeping on the ground, wearing dirty clothes, and getting very little food; during this time, she also lost her status as a lady of the house and whatever domestic authority she may have wielded. According to the dharma literature, all of this ended with a bath at the end of her menstrual cycle, after which she was accepted back at her former status. Women who conceived as a result of adulterous liaisons were abandoned. In practice, this often meant being secluded and cut off from the family, although she still received food. Abandonment was also recommended in certain other cases: in adulterous liaisons with a man’s student or his guru, if a woman attempted to kill her husband, or if she killed her fetus. The reluctance to completely cast a woman away, and the willingness to bring her back to her former status after doing penance, both reflected the importance of marriage and family life in Hindu culture, as well as women’s importance in the family. 23

Children

After a child was born, Namakarna was the rite of conferring a name on the new born child. The prescribed day for this samskara was the tenth or the twelfth day, when the mother left the child bed. 24

The children were happy adjuncts of the house hold. The mothers who gave birth to children, fondled them in the knee, were considered happy; the childless women (nindu) were taken as unlucky, so they yearned for children and propitiated various deities to obtain them. The child possessing the entire and complete five sense organs, with the lucky sign, marks and good qualities, well-formed and having full weight and length was considered good.

Dreams also played an important part in the birth of a child in the life of ancient Indians. There was a regular science of dreams (sumanasa-tha) and books were written on the subject; it is considered as one of the eight divisions of mahanimitta.

In Jain texts, usually a mother before conception saw certain dreams. We learn that at the time of the conception of mahavira, his mother had fourteen great dreams in which she saw an elephant, a bull, a lion, the besprinkling of goddess Sri, a garland, the moon, the sun, a banner, a jar, a lotus-pool, the sea, the celestial palace, a heap of jewels, and fire. The nayadhammakaha gives a similar description of dharini’s dreams; she saw a big elephant passing into her mouth during the night of her conception. 25 After their birth, children received auspicious names hence they were often named after deities and heroes. 26

Infanticide

In ancient India, female infanticide was practiced on a large scale because many elite Hindu communities preferred a son for both religious and secular reasons. Sons had to perform their father’s cremation rituals (sraddha), for instance, although some lawgivers allowed a daughter or other relative to do this if there were no son. 27 Daughters were so devalued that they were sometimes accepted as punishment for sins of the past life. 28 Several examples of infanticide are given in Hindu mythology, of which the best known is Kunti. Kunti was given a mantra by the sage Durvasas, which gave her the power to conceive and bear children by the gods. On a whim, Kunti impulsively used the mantra to invoke the Sun, by whom she conceived and bore her son Karna. In her panic at unexpectedly becoming a mother as she was still unmarried, and understandably concerned about what people might think, she placed the child in a box and abandoned him in the Ganges. 29 The people of ancient India considered children, especially girls as a burden and didn’t want to keep them. Hence, they constitutionalized it by making it a part of their forged religion. Secondly, since prostitution and incestuous relationships were prevalent in the society and they had no way of hiding their illegal children, they would get rid of them by killing the little babies in cruel ways.

Slaves

Slavery existed in ancient India, as is recorded in the Sanskrit Laws of Manu of the 1st century BCE. 30 Slaves, also known as unfree labor were also mentioned in the early Buddhist literature, the Jatakas and the Dharmasutras. Slaves were often employed to serve in their master’s household or performed other duties in the field. The causes of slavery were many, e.g., capture in war, judicial punishment or degradation, voluntary enslavement and slavery for non-payment of debt. The jatakas, too, speak of four kinds of slaves such as: children of slaves, those who sell them-selves to others for food or protection, those who recognized others as their owners, those sold for money.

Large numbers of men seem to have been reduced to slavery, by the raiding forays of robbers who captured men and women and sold them into slavery. Others appear to have lost their freedom, as punishment for heinous crimes. Most of the slaves were domestic servants and were probably well treated, though violence to them was not illegal. They resided in the family of the master and performed all sorts of household duties.

This was however the better side of the picture. In the hands of cruel masters, the life of the slave was miserable. It is recorded in the Namasiddhika that the master and mistress of the slave girl Dhanapali, beat her and put her on hire to work for others. Moreover, it lay in the power of the master, to beat his slave, to imprison him or to brand him with a red-hot metal.

The chief difficulty with the slave was his loss of persona. Nothing except freedom could improve this social degradation. The marriages of slave with free-women hardly improved their status. Sons of slave girls by their masters were hardly regarded as free-men. Stories of intimacy of masters with slaves and of a master’s daughter intimacy with a slave were common. Many slaves ran away from their masters, crossed the frontier and improved their position by marrying the daughters of respectable people.

There were regulations for the manumission of slaves on account of ill treatment or if the slave was able to pay their own ransom. The Buddhists regarded slaves as the property of their masters and did not allow them to enter the order. Other religious orders seem to have admitted them, and admission into any religious order made them free men.

The price of slaves varied with their accomplishment, good birth or (if a woman) beauty. In the Vessantara Jataka the princely father, when parting from his boy and daughter, spoke of the daughter as being only fit for a princely purchaser who could offer 100 Niskas, in addition to a hundred slaves, horses, cows and elephants. In the case of the prince his ransom-money was estimated only at 1000 Kahapanas. 31

Stages of Life

An Ashrama in Hinduism was one of four age-based life stages discussed in Indian texts of the ancient eras. When the twice born came of age, they entered into the four ashramas or spiritual stages of life. The first ashrama was Brahmacharya, or the stage of the student. For boys, the student was supposed to live with a teacher (guru), who was traditionally a Brahmin by birth, but who at least needed to be renowned for having spiritual knowledge. Girls were usually trained by the parents, with specific gurus for particular interests. Here the student learned Sanskrit, the Vedas, rituals, and so on. The dharma of a student included being learned, gentle, respectful, celibate, and nonviolent.

The second stage was Grihastha, or the stage of the householder, that is, married life, which was taken far more seriously in Hinduism than in Jainism, Buddhism, or in the other ascetic traditions. It was usually regarded as mandatory, and was considered just as important for spiritual development as was being a student. It was usually at this stage that one’s sva-dharma, or psychophysical leaning, was assessed by the guru, and it was also here that most people performed their most important religious functions (known as samskaras, or “rites of passage”).

The third stage of spiritual stratification was called Vanaprastha, the forest dweller, or the stage of retirement. Husbands and wives left their secular affairs and possessions with their now grown children, if they had any, and retired to the forest as hermits. This did not involve the complete renunciation of the world, for husbands and wives could still have minimal relations, but the idea here was that they were preparing for renunciation, which, in turn, was meant to prepare them for death. The Aranyakas (“Forest Treatises” associated with Vedic texts), were written by and for people who were at this stage of life, who had largely renounced the world and were starting to seriously consider liberation.

In old age, one traditionally entered the fourth stage of Sannyasa, or that of the wandering ascetic, which was the most respected of all the ashramas. The sannyasiis considered the spiritual master of society. Ideally, the sannyasi was a sadhu, or a holy person, who wandered the countryside dedicated to renunciation, to developing his own consciousness, and to instructing others, without worldly distractions. 32

Prostitution

In ancient India, practices of prostitution were closely connected with religious rituals 33 and Hindu society regarded sexual expression as an important component of life. While a variety of different approaches to sexual behavior existed, many Hindus were taught that sex was an activity to be enjoyed and not repressed. 34 Women who had acquired expertise in sex enjoyed great esteem. Prostitution had a recognized social function, while polygamy and the company of beautiful women were considered features of sophisticated urban life in India’s patriarchal past. Prostitutes and ganikas, unlike wives, were free. 35 The wife had to stay at home, and supervise the cooking and care of the young children, while the courtesan conversed freely with many men. If she was intelligent, she had it in her power to sway the destinies of the state. 36

In ancient India, the prostitutes had many nicknames which were based on their various traits. Those nicknames were: Bandhaki (related to many men through passion), Rupajiva (one who earned livelihood by beautiful appearance), Vesya (one who caused delusion in man by dress), Ganika (who lived in ganas or groups, or enjoyed by a number of people), Varangani (one who was enjoyed by turn), Kultani or Sambhali (one who procured passionate people), pumscali (who ran after a man), Kumbhadashi and Paricarika (a woman in keeping). Furthermore, prostitutes of three other kinds were also mentioned: Ekaparigraha (attached to one), Anekaparigraha (attached to many) and Aparigraha (not attached to a particular individual). 37

It was from Egypt that legal prostitution found way into India during the Brahmin period. It was Deerghatama, the prurient saint and blind poet (probably of the Brahmin period) who brought the cult of inviolable chastity for married women only, and quite unknowingly paved the way for professional prostitution in India. His law prepared the soil on which the Egyptian seed fell and soon, at the end of the Brahminic period, prostitution had passed for a profession.

The account states that Deerghatama was disturbed in the womb of his mother by the unbridled passion of his uncle and possibly this had the effect of giving him an erotic disposition. Though vastly learned in Veda and Vedanga, he used to indulge in public spooning and incestuous relationship like the cattle. Later on, he was thrown in to the river by his sons on his wife’s orders, but still, he managed to live long enough to lay the foundations of professional prostitution. 38 Prostitutes or courtesans were a regular feature of ancient Indian life. But far from simply offering sexual pleasure, these prostitutes were in many cases women of culture and learning. 39 In that society, prostitution was given so much fame that girls would long to learn the skills required for being the best pleasure giver so that they would not only accumulate wealth, but reach positions of power as well. As a result, their offspring used to turn out more corrupt and would have no respect for their parents or the society. It is astounding really that even some contemporary societies long for such societies in which the value and respect for a woman was nothing more than a tool for pleasure.

Homosexuality

Homosexuals existed in ancient India 40 and were mentioned in the Dharmasastras and Epics, Ayurvedic texts and Kamasastra. The Kamasutra of Vatsyayana, was one of the few Sanskrit sources that affirmed same-sex relations in the context of discussing varieties of sexual experience. Its ninth chapter, called Auparistaka or ‘Oral Sexual Activity’ mentioned persons of a third nature (tritıyaprakrti), some of whom engaged in same-sex activity. 41 As far back as the Vedic period, the Indian worldview included the acceptance of a third sex (tritiyaprakcta) described as “neither man nor woman” (napuusaka) literally “non-male”, existing alongside the female and the male. Most authorities understood this third sex as comprising persons of non-normative gender behavior or sexual functioning, such as impotent males, cross-dressers and transgendered persons, hermaphrodites and eunuchs. Also included among the third sex were those men and women who engaged in same-sex sexual relations. Normative males who had sexual relations with other normative males were not usually reckoned as members of the third sex. 42 The Kamasutra also speaks of urban male sophisticates (nagarikas) who for mutual pleasure engaged in sexual activity with each other. 43

Vatsyayana (the writer of Kamasutra), included a whole chapter on the practice of fellatio as performed by the eunuchs. Other erotic manuals suggested that sodomy was common in Kalinga (southern Orissa state) and Panchala (in Punjab). In general, sex for pleasure was explicitly validated and was not necessarily linked to procreative function. 44

Texts such as The Law Code of Manu (100 A.D.) mentioned fines and expiation rituals for homosexual activity. The sparse references to homosexuality in Brahmanic literature reflect more the purpose of these texts than the social history of homosexual activity in South Asia. 45

Lesbianism

India had a very rich culture of lesbian desire in the early pre-Vedic cultures prior to 1500 B.C. Lesbianism was represented through the concept of Jami (the feminine twins). The notion of twins was not based on a biological identity but that of a holistic union between women that comprised both erotic and sexual dimensions. 46 The Kamasutra used words such as Purusarupin (‘a woman in the form of a man’) and svairin (‘independent woman’), and these were often used in the context of female homosexual activity. This was described in detail in Kamasutra, in which one woman penetrates another using a device, or apadravya. 47

Manu (100 BCE to 100 CE), the compiler of Hindu law code, had stipulated harsh punishment for homoerotic behavior of both males and females. A stri (woman) indulging in sexual intercourse with a kumari(virgin) would get punishment in the form of a shaved head, two chopped fingers, and a ride on a donkey. If it were between two virgins, punishment would be ten lashes, a fine of 200 panas, and the doubling of marriage fees.

Despite the taboo against lesbianism, the ideal of heterosexual union was not always followed. References to lesbian love, passion, and sex in Hinduism are found in literature, art, and narratives on social behavior. Radha, the consort of Krishna, had many sakhis (female friends) and their close friendship had been interpreted as homoerotic behavior by some authorities.

Maharishi Vatsayana’s Kamasutra, a classic work on social conduct and sexual arts, contained descriptions of virile behavior in women. The Kamasutra refers to positions like “thunderbolt” and “wild boar’s thrust,” which were cited as examples of same-sex behavior between women. It is apparent that royal females had lesbian affairs with their maidservants, who were asked to dress as men and often used dildos. While talking about tritiyaprakriti (people of the third sex), Vatsayana refers to the svairini (lesbian) having somewhat purushayita, or aggressive behavior. The svairini was an independent woman without a husband. Fending for herself, she used to live alone or in conjugal bliss with a person of her gender. 48

Housing and Infrastructure

The ruins of two ancient Indus Valley cities, Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa depict much about urban planning in the Indus Valley. Both cities, which were about one square mile in size, were planned cities with similar rectangular layouts. Indus Valley cities had two distinct sections: a walled citadel, which included such features as administrative buildings, religious centers, bathhouses, and granaries; and a lower town, or residential area. The lower town was also protected by walls to protect it from floods. Streets were laid out in grids that formed blocks with homes. Although many homes had only one room, others contained multiple rooms and stories. Some contained inner courtyards and brick staircases that led to upper floors or roofs. Most buildings were made from baked bricks. There appear to have been no palaces within Indus Valley cities. The Indus Valley civilization was advanced in many ways, including residential plumbing. Some homes were equipped with bathrooms that included toilets and baths. Houses received their water from their own wells, located in the home’s courtyard, or from a public well. A drainage system, located underneath the streets, removed the water from the homes. This plumbing system helped to maintain the health of the cities’ residents. Public bathhouses, and bathing in general, may have been associated with religious rituals. 49

Food

As regards to food and drinks, and the modes of cooking, serving and eating differed with different peoples and social grades in different localities. The Kambojas of Uttaarapatha are said to have eaten insects and some variety of moths, snakes and frogs. In deserts of Rajputana and other parts of India some cannibals were also known to have existed which lived off human flesh. There was a class of hermits as well who used to subsist on the meat of elephants and the hunters as a class are said to have eaten even the flesh of lions, tigers, bears, panthers and hyenas. 50

Food played a major role in Hinduism. All sacrifices involved food, and only the best was deemed fit for the gods. The Upanisads interiorize the role that food played: everything was seen as arising from food and becoming food again. Preparing and consuming food was regulated by a host of rules. Many caste regulations concerned commensality. While Vedic Indians seem to have had few, if any, restrictions with regard to food (apparently the animals that were unfit for sacrifice, such as donkeys and camels, were also unfit for eating). With the ascendancy of Buddhism and Jainism, most Hindus, especially the Brahmins, seem to have adopted vegetarianism. Vaisnavas in particular developed a whole theology of food: categorizing all foods according to the three Gunas, they advised the taking of sättvik food (milk and milk products, most grains, fruit and vegetables) and the avoidance of räjasik food (‘exciting’ foods such as garlic, eggs, red-colored vegetables and fruit) and tämasik (‘foul’ foods such as meat and intoxicating substances). Saivas and Säktas observed few restrictions with regard to food. 51

The groups with the highest status, particularly Brahmins, were the strictest withregard to their dining habits. For the most part, such high-status groups adhered to a principle known as commensality—that is, only eating food cooked by member of their social group. With regard to the content of one’s diet, the great divide was between vegetarian and non-vegetarian. An exclusively vegetarian diet indicated higher status, and among non-vegetarians there were status gradations depending on what types of meat one ate. For orthodox Hindus, every meal was a potential source of ritual contamination and needed to be carefully monitored. Food cooked in water was seen as far more susceptible to pollution and greater care was taken in accepting it, whereas food fried in oil or ghee was believed to be much more resistant to pollution and thus a lesser source of ritual danger. 52

Still, Hindus did not accept vegetarianism across the board. Shaktas, for example, performed animal sacrifices, and ate the remaining flesh as a special benediction from God. 53 The Rigveda and later Vedic writings indicate that meat eating (even beef) was common in ancient India, especially in connection with animal sacrifices. When Jainism and Buddhism protested against the killing of animals both for ritual and commercial purposes, vegetarianism also became popular in Hinduism, particularly among vaisnavas, who ceased to perform animal sacrifices. However, beef eating had ceased long before Manu, because the Manu-Smrti provides punishments for killing a cow, almost as severe as those for killing a Brahmin. Saivas and Säktas continued to eat meat, especially goat and chicken, but also buffalo and deer. 54

Cow

For the Vedic Aryan, the cow was the symbol and currency of wealth; its energy could be harnessed for the production of food (milk and its derivatives, and various crops through tilling the earth) and for trade and transport. Thus, the cow was also a symbol of security and well-being. 55 Hindus also had deep regard for her five products—milk, yogurt, clarified butter (ghee), urine, and dung. 56 Since the Hindus had a high regard for the cow and all her products, it was no wonder that these people used to drink its urine on a consistent basis as well.

Clothes

The dress of the people varied along with their features. Sources also show that at times nudity was also prevalent in ancient times. 57 For the Pallava, Pandya, Chola and Vijayanagar periods, inscriptions and literature provide a good account of the dress of the people. Visual representations were provided by the sculptures and paintings of this period. Adequate representations were available from sculptures and paintings. By looking at the sculptures and paintings through the ages, some scholars are of the opinion that Indians as well as the women of the Tamil country were bare above their waists from early times. The sculptures depicted the women with bare breasts and a lower garment. 58

Historical record of Indian clothing is not easy to trace. While there is an abundance of sculpture and literature dating from the earliest periods of civilization in the Indus Valley (which flourished along the Indus River in modern-day Pakistan) around 2500 B.C.E., scholars have had difficulty dating the changes in clothing styles and naming the variations on certain styles over time. Another problem in identifying trends in Indian clothing is the abundance of different ethnic and cultural groups that have lived and are living in the country; each of which has its own distinctive style. These circumstances make it possible to make generalizations about Indian clothing, but not to make concrete statements about each and every style worn in the country.

The oldest type of Indian clothing was fashioned out of yards of unsewn fabric that were then wound around the body in a variety of ways to create different, distinct garments. This clothing was woven most commonly out of cotton but could also be made of goat hair, linen, silk, or wool. 59

In the Sangam Age, women wore different kinds of clothes. They wore a lower garment and an upper garment. The women wore clothes called kalingam which was usually made of cotton. Barks of trees and plaited leaves particularly of Asoka tree were also used as a dress. In ancient Tamilnadu, women also wore some special dress, strewn with leaves and flowers. It is said that women of the Neidal region beautified themselves with garments sewn with the leaves and punnai flowers. This kind of dress appears to have been used on special occasions and festivals. The girls of the hunter community also dressed themselves with leaf garments. Coconut fibers were used to make garments and they seem to have been worn then. Animal hair, and vegetable fibers were also used to make dresses. It appears that even after the use of cotton, silk and woolen clothing in the Sangam Age, the use of leaf garment was not given up totally, particularly by the people of the lower strata. The decorations and the designs of the dress either printed or woven leave an impression that the people of the Sangam Age were eager to put on an elegant appearance. The evidence with regard to their upper garment was very scanty. This has led to suggest that ancient women of the Tamil country went bare breasted. 60

Some of the most popular garments are a wrapped dress called a sari, a pair of pants called a dhoti, a hat called a turban, and a variety of scarves. These styles of garments have been popular in India since the beginning of its civilization. 61 An undergarment and an upper garment were in general use among the members of both the sexes. A waistband was used round the lower garment. Both the garments were colored, especially in the case of a woman. 62

Marriage

According to tradition, marriage did not exist in the early times. It was introduced by the sage Ÿvetaketu, after an incident involving his mother. Since then it has been of utmost importance to Hindus. Only a married couple was seen as a complete ‘unit’ for worship and participation in socially relevant acts. Vivahawas the most important Sanskara (rite of passage), the only one for women. 63

Marriage, the strongest bond between a man and a woman, was one of the most important social and economic institutions of ancient India. It was not only the union between a man and a woman, but also of two families. Marriage was also understood as a sacrament between two souls and not just a contract between two human beings. For most Hindu women, being wives and mothers defined their identity. Marriage was also the event by which families were formed and expanded. Since the family was considered the bedrock of Hindu society, for most people, marriage was the single most important event in their lives. 64

Eight types of marriage (vivaha) existed in ancient India; the first four were socially approved, and the last four were not. Authorities ranked bride capture among the socially unapproved marriages. The first and highest form of socially approved marriage, roughly in the order of decreasing acceptance was Brahma vivaha. This was the marriage of a well-dressed ornamented girl to a man of the same social class. Second was Daviavivaha which can be understood from the following detail. A property owner invited a scholar to his home and requested him to perform certain rites. He then presented his daughter to the scholar as part of his professional fee and mark of respect. This shows that the daughter was married off to a stranger as part of a payment.

Third was Arshavivaha; in this type, dowry was not paid, but the bridegroom gave a cow and a bull to the bride’s parents as a token bride price or a gift out of respect. Finally, the groom’s family also did not pay bride price with Prajapatyavivaha. It was similar to civil marriage without fanfare.

Socially unapproved marriages, roughly in order of decreasing social approval, began with Gandharvavivaha or love marriage. Second, Asuravivaha was a demon or barbaric marriage, whereby a man or his family purchased a girl for that purpose. Third there was Rakshasa vivaha, a devil marriage, or marriage by capturing or kidnapping a girl. Finally, Paishachavivaha was a ghost marriage, whereby some wicked person raped a girl and later offered marriage in compensation. 65

The father had the express and holy duty to find a husband for his daughter. 66 However, in the Vedic ages, women seemed to have had the power of choosing her husband, but that trace of time and environment in which her sex was predominant disappeared in the classical period. Far from a union being the result of elective affinities between individuals, it was normally arranged by the families and consecrated in the childhood of the future husband and wife. The Dharma Sutras of Gautama already declared that girls needed to be married before puberty, and eventually children were married in their very early years, long before the girl aged eleven or twelve, and went to live in her husband’s house. In consequence, many women became widows when quite young, before the union even physically consummated. The same work allowed the childless widow to remarry, but greater esteem was enjoyed by the woman who resigned herself to lifelong widowhood, even if her husband died at age three or four years of measles or whooping cough. This feeling was so strong that a woman who lost her husband at adulthood is encouraged to allow herself to be burned on his funeral pyre. 67

The ceremony of marriage was an appropriate one, and the promises which the bride and the bridegroom made were suitable to the occasion. 68 After an auspicious wedding-day was selected, the day before the wedding was set apart for a ceremony of the bridegroom, which indicated that he had completed certain studies of the Vedas since he received the sacred thread. Offerings were made to fire, and the locks of hair which were supposed to be left standing at the five places on his head at the former ceremony, were removed.

Then followed a make-believe performance, in which the bridegroom pretended to be seeking for a bride, and as he found none, he prepared himself to go to the sacred river Ganges. Then a friend of his, used to come forward with a promise that he will give his sister or daughter in marriage to him. The bridegroom then stopped the preparation for his journey to the Ganges and said he was ready for the wedding.

A few hours before the marriage, the bridegroom’s father sent a beautiful cloth for the bride and one for some other person in the house. This was the conclusion of the betrothal. The bridegroom then set out with all his male relatives and friends and marched in a brilliant procession to the house of the bride. After he had been received, the bridegroom and the bride were seated in the midst of the assembly on a wooden stool made for the occasion.

The family priests of both parties and other aged and learned men, then repeated a number of texts from the Vedas, and also the names of the ancestors of the bride and bridegroom. After this, the bride’s father, or whoever gave her away, washed the feet of the bridegroom with water and milk. A yoke was then brought and held above the head of the bride by two men, while the bridegroom repeated a few texts from the Vedas and poured some water on her head. Then followed the tying on of the tali or marriage badge. This was a thin circular piece of gold tied to a string and worn around the neck. It was first passed around, and all the guests touched it, wishing happiness and prosperity to the young couple.

Then two large plates of rice were brought, which the family priest took; and while he repeated the sacred texts, he puts the rice, first into coconut shells and then upon the heads of the bride and the bridegroom. The clothes of the bride and the bridegroom were then tied together and while the family priest is repeating sacred texts, they made offerings to fire. On the evening of the first day of the marriage, another offering was made to the gods, the bride and the bridegroom walk around the fire and in seven steps come to a certain stone which they together touched with their feet. This was a symbol that they were to live together until death.

In the main the rest of the performances consisted in offerings to the gods, repeating sacred texts, distributing food and money to Brahmans, and marching along the streets in brilliant processions. This was the first and principal marriage, and took place while both bride and groom were very young. After a number of years when they went to live together as husband and wife, another marriage ceremony, extending over three days, followed, which was less showy but expensive.

The above description answers more particularly to the marriage ceremonies as observed by Brahmans. Among low-caste people, also, marriage was made a great occasion, but it was attended with less brilliancy and fewer rites. 69

Divorce

From its very idea of a sacrament, a Hindu marriage in ancient India was held to be indissoluble. The effect of the marriage upon the wife was to transfer, both bodily and spiritually from her paternal family to that of her husband. She adopted the gotra of her husband and became united to him in flesh and blood. During the husband’s lifetime, he was regarded by the wife as god and the wife was declared to be the half of the body of her husband, equally sharing all his acts and no sacrifice and religious rite was allowed, apart from the husband. The union was a sacred tie and subsisted even after the death of the husband. This view in ancient times led to many consequences. Being the union of two souls, the death of husband did not set the wife free to remarry. Again, during the husband’s life-time there could be no divorce for whatsoever reason. Neither adultery, nor prostitution, nor degradation could ever dissolve a Hindu marriage. 70

There is little evidence of divorce as a legal category in Vedic and post-Vedic literature. The ninth chapter of the ancient law book of Manu explained an orthodox position that husband and wife were to be seen as one entity and, just as an estate is only divided once, so too the bond of marriage ought to be performed only once. Neither by sale nor separation, it goes on to say, can a husband and wife be severed from each other. Although these authoritative texts do not deal with the question of dissolving the sacrament of marriage, Hindus were familiar with divorce in the area of custom—another acknowledged source of law. 71

Un-Chastity

Infidelity existed in ancient India as some wives were hostile and unfaithful to their spouses. They used to receive their lovers at home while their husbands were out and had illicit sexual relations with them. Giddy girls, not well looked after by their brothers also went astray and fondly went to the place where they expected to meet their lovers. Children which were born out of these illegal relations were abandoned. 72 The stories of such lovers were later made in to Indian legends and were celebrated even though this practice was a nuisance for the society.

Widow Remarriage

The position of a widow who wished for a second husband, was clearly defined by Vatsyayana. There was no regular marriage for a widow; but if a woman who had lost her husband, was of weak character and was unable to restrain her desire, she could ally herself for a second time to a man who was a seeker after pleasures (bhogin) and was desirable on account of his excellent qualities as a lover and such a woman was called a Punarbhu. When the Punarbhu went to seek her lover’s house, she assumed the role of a mistress, patronized his wives, was generous to his servants and treated his friends with familiarity; she chided the lover herself if he gave any cause for quarrel. She needed to show greater knowledge of the arts than his wedded wives and seeked to please the lover through various arts. She could leave her lover, but if she did so of her own accord, she would have to return all the presents given by him, except the tokens of love, mutually exchanged between them; if she was driven out, she did not give back anything. 73 Those widows who remained unmarried and had a desire for sex, were also allowed to cohabit with the brother of the deceased husband. 74

Incest

As with many other ancient non-divine religious cultures, incest was also practiced in the ancient Indian society. This incestuous practice was also endorsed by at least one mythic narrative in Hinduism which stated that incest was a primeval act of creation. One well known story from Vedic literature explained that the divinity responsible for creation (Prajapati or Brahma) seduced his own daughter, the Dawn (Ushas), to set in motion the process of populating the earth. 75 There were tantric texts within the broader fold of Hinduism which state that it is a sacred duty to practice incest. In these tantras, incest was permitted with mothers, sisters, daughters and low born maids. 76

When the minds of ancient India concocted a religion based on personal lust, greed and thirst for power and wealth, resultantly, a society came in to being whose value system consisted of Immorality, Chaos, Prostitution, Homo-sexuality, Incest, Infanticide and other evils. It was considered normal for them if their women or men wandered about, partially or completely naked. On the other hand, societies which were based upon the divinely revealed religions were stable and their value system consisted of justice, morality, ethics, modesty, and respect and love for everyone. To maintain such societies and to invite others to live prosperously, prophets kept coming to this world overtime but not every society accepted their invitation, and those which didn’t ended up like the society of ancient Indians.

- 1 Virginia Schomp (2010), Ancient India, Benchmark Books, New York, USA, Pg. 16

- 2 Justice Markandey Katju (2010), Ancient Indian Jurisprudence, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India.

- 3 Klaus K. Klostermmair (1998), A Concise Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Oneworld Publications, Oxford, U.K.., Pg. 27-28.

- 4 Dr. Pran Nath (1929), A Study in The Economic Condition of Ancient India, The Royal Asiatic Society, London, U.K.., Pg. 117-118.

- 5 Steven J. Rosen, foreword by Graham M. Schweig (2006), Essential Hinduism, Praeger Publishers, Westport, USA, Pg. 207-208.

- 6 Klaus K. Klostermmair (1998), A Concise Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Oneworld Publications, Oxford, U.K., Pg. 47.

- 7 D. D. Kosambi (1964), The Culture and Civilization of Ancient India in Historical Outline, Pune, India, Pg. 14.

- 8 Julius Lipner (1994), Hindus, Their Beliefs and Practices, Routledge, London, U.K.., Pg. 3.

- 9 Bimala Churn Law (1947), Ancient India: 6th Century B.C., The Indian Research Institute, Calcutta, India, Pg. 11.

- 10 Junious P. Rodriguez (1997), The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery, ABC-Clio, California, USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 617-618.

- 11 Rama Shankar Taripathi (1942), History of Ancient India, Jahendra Press, Delhi, India, Pg. 49.

- 12 Bimala Churn Law (1947), Ancient India: 6th Century B.C, The Indian Research Institute, Calcutta, India, Pg. 11.

- 13 Yudit Kornberg Greenberg (2008), Encyclopedia of Love in Ancient Religions, ABC-Clio Inc., California, USA, Pg. 196.

- 14 Jagdish Chandra Jain (1947), Life in Ancient India as Depicted in the Jain Canons, New Book Company, Bombay, India, Pg. 152.

- 15 Constance A. Jones & James D. Ryan (2007), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 499.

- 16 Klaus K. Klostermmair (1998), A Concise Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Oneworld Publications, Oxford, U.K.., Pg. 209.

- 17 P. T. Srinivas Iyengar (1912), Life in Ancient India in the Age of the Mantras, Srinivasa Varadachari, Madras, India, Pg. 66.

- 18 Nundolal Dey (1903), Civilization in Ancient India, New Arya Mission Press, Calcutta, India, Pg. 157.

- 19 James G. Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, The Rosen Publishing Group Inc., New York, USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 773.

- 20 Rama Shankar Tripathi (1942), History of Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidas, Delhi, India, Pg. 50.

- 21 Jagdish Chandra Jain (1947), Life in Ancient India as Depicted in the Jain Canons, New Book Company, Bombay, India, Pg. 152.

- 22 Lyn Tesky Denton (2004), Female Ascetics in Hinduism, State University of New York Press, New York, USA, Pg. 25-26.

- 23 James G. Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. New York. USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 11.

- 24 Kamalabai Deshpande (1936), The Child in Ancient India, Aryasamskriti Press, Poona, India, Pg. 100.

- 25 Jagdish Chandra Jain (1947), Life in Ancient India as Depicted in the Jain Canons, New Book Company, Bombay, India, Pg. 147-148.

- 26 Cybelle Shattuck (1999), Religions of the World: Hinduism, Routledge, London, U.K., Pg. 81.

- 27 Denis Cush, Catherine Robinson & Michael York (2008), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Routledge, London, U.K., Pg. 373.

- 28 Helen Tierney (1999), Women’s Studies Encyclopedia, Greenwood Press, Connecticut, USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 737.

- 29 James G. Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, The Rosen Publishing Group Inc., New York, USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 302.

- 30 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/topic/slavery-sociology: Retrieved: 24-04-2018

- 31 N. C. Bandyopadhyaya (1980), Economic Life & Progress in Ancient India, Kharbhanda Offset, Allahabad, India, Pg. 268-271.

- 32 Steven J. Rosen (2006), Essential Hinduism, Praeger, London, U.K., Pg. 44-45.

- 33 Chris Kramarae & Dale Spender (2000), Routledge Encyclopedia of International Women, Routledge, London, U.K., Pg. 1679.

- 34 Jeffery S. Turner (1996), Encyclopedia of Relationships across the Lifespan, Greenwood Press, Connecticut, USA, Pg. 58.

- 35 Melissa Hope Ditmore (2006), Encyclopedia of Prostitution and Sex Work, Greenwood Press, London, U.K., Vol. 1, Pg. 303.

- 36 Leo Markun (1925), Prostitution in the Ancient World, Haldeman-Julius Company, Kansas, USA, Vol. 286, Pg. 43.

- 37 Sures Chandra Bannerjee (1980), Crime and Sex in Ancient India, NayaProkash, Calcutta, India, Pg. 83-84.

- 38 S. N. Sinha & N. K. Basu (1933), History of Prostitution in India, The Bengal Social Hygiene Association, Calcutta, India, Vol. 1, Pg. 28, 38-40.

- 39 James G. Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, The Rosen Publishing Group Inc., New York, USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 528.

- 40 Robert T. Francouer & Raymond J. Noonan (2004), The Continuum Complete International Encyclopedia of Sexuality, Continuum, New York, USA, Pg. 524.

- 41 Denis Cush, Catherine Robinson & Michael York (2008), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Routledge, London, U.K., Pg. 354.

- 42 Jeffery S. Siker (2007), Homosexuality and Religion: An Encyclopedia, Greenwood Press, London, U.K., Pg. 77.

- 43 George Haggerty (2012), Encyclopedia of Gay Histories and Cultures, Routledge, London, U.K., Pg. 467.

- 44 Wayne R. Dynes (1990), Encyclopedia of Homosexuality, Routledge, London, U.K., Vol. 1, Pg. 587.

- 45 Yudit Kornberg Greenberg (2008), Encyclopedia of Love in Ancient Religions, ABC-Clio Inc., California, USA, Pg. 307.

- 46 Bonnie Zimmerman (2000), Encyclopedia of Lesbian Histories and Cultures, Garland Publishing Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 391.

- 47 Denis Cush, Catherine Robinson & Michael York (2008), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Routledge, London, U.K., Pg. 461.

- 48 Yudit Kornberg Greenberg (2008), Encyclopedia of Love in World Religions, ABC-Clio, California, USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 362.

- 49 Wendy Conklin (2006), Ancient civilizations, Scholastic Teaching Resources, Pennsylvania, USA, Pg. 30.

- 50 Bimala Churn Law (1947), Ancient India: 6th Century B.C., The Indian Research Institute, Calcutta, India, Pg. 15.

- 51 Klaus K. Klostermmair (1998), A Concise Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Oneworld Publications, Oxford, U.K., Pg. 69.

- 52 James G. Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. New York. USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 217.

- 53 Steven J. Rosen (2006), Essential Hinduism Praeger Publishers, Westport, USA, Pg. 181.

- 54 Klaus K. Klostermmair (1998), A Concise Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Oneworld Publications, Oxford, U.K., Pg. 116.

- 55 Julius Lipner (1994), Hindus, Their Beliefs and Practices, Routledge, London U.K.., Pg. 37.

- 56 Steven J. Rosen (2006), Essential Hinduism, Praeger Publishers, Westport, USA, Pg. 184.

- 57 Rama Shankar Tripathi (1942), History of Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidas, Delhi, India, Pg. 21.

- 58 Shodhganga: A Reservoir of Indian Thesis: http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/132001/11/11_ch apter%205.pdf: Retrieved: 12-04-19

- 59 Sara Pendergast & Tom Pendergast, Fashion, Costume and Culture: The Ancient World, Thomson Gale, New York, USA, Vol. 1, Pg. 75.

- 60 Shodhganga: A Reservoir of Indian Thesis: http://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/132001/11/11_cha pter% 205.pdf: Retrieved: 12-04-19

- 61 Sara Pendergast & Tom Pendergast, Fashion, Costume and Culture: The Ancient World, Thomson Gale, New York, USA, Vol. 1, Pg. 75.

- 62 Simmi Jain (2003), Encyclopedia of Indian Women through the Ages: Ancient India, Kalpaz Publications, Delhi, India, Vol. 1, Pg. 103.

- 63 Klaus K. Klostermmair (1998), A Concise Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Oneworld Publications, Oxford, U.K., Pg. 114.

- 64 James G. Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, The Rosen Publishing Group Inc., New York, USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 427.

- 65 David S. Clark (2007), Encyclopedia of Law and Society, Sage Publications, London, U.K., Vol. 1, Pg. 134.

- 66 Johan Jakob Meyer (1930), Sexual Life in Ancient India: A Study in the Comparative History of the Indian Culture, George Routledge and Sons, London, U.K., Vol. 1, Pg. 54.

- 67 Paul Masson Oursel (1934), Ancient India and Indian Civilization, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 78.

- 68 John Adam (1904), Epochs of Indian History: Ancient India: 2000 B.C-800 A.D., Longman’s, Green and Co., London, U.K., Pg. 23.

- 69 Rev. A. D. Rowe (1881), Every Day life in India, American Tract Society, New York, USA, Pg. 99-101.

- 70 Prof. Indra (1940), The Status of Women in Ancient India, The Minerva Book Shop, Lahore, Pakistan, Pg. 100-101.

- 71 Yudit Kornberg Greenberg (2008), Encyclopedia of Love in Ancient Religions, ABC-Clio Inc., Santa Barbara, California, USA, Pg. 170-171.

- 72 P. T. Srinivas Iyengar (1912), Life in Ancient India in the Age of the Mantras, SrinivasaVaradachari, Madras, India, Pg. 67.

- 73 H. S. Chakladar (1954), Social Life in Ancient India, Susil Gupta Ltd., Delhi, India, Pg. 127-128.

- 74 P. T. Srinivas Iyengar (1912), Life in Ancient India in the Age of the Mantras, SrinivasaVaradachari, Madras, India, Pg. 69.

- 75 Yudit Kornberg Greenberg (2008), Encyclopedia of Love in World Religions, ABC-Clio, California, USA, Vol. 1, Pg. 320.

- 76 Hugh B. Urban (2003), Tantra: Sex, Secrecy, Politics, and Power in the Study of Religion, University of California Press, Los Angeles, USA, Pg. 52, 60.