- Home

- About Us

- Contribute

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Contact Us

Religious Beliefs of Ancient Egypt

Beliefs: Egyptians practiced polytheism; worshiping over 2000 gods integrated into daily life.Pharaoh's Role: Pharaohs were seen as divine intermediaries maintaining cosmic order through rituals.Animal Worship: Deities were often depicted as animals or hybridsGods and Pantheon: Included state gods (e.g. Amun; Osiris); local gods; and household deities; reflecting hierarchy.Creation Myths: Varied myths explained creation; often conflicting and tied to natural forces.Magic and Amulets: Magic (Heka) was central; with amulets for protection and healing.Afterlife: Elaborate burial practices aimed at securing immortality through the ka and ba (soul concepts).Outcome: Their manmade beliefs led to their spiritual; religious and societal decline.Languages

اردوReligious Beliefs of Ancient Egypt

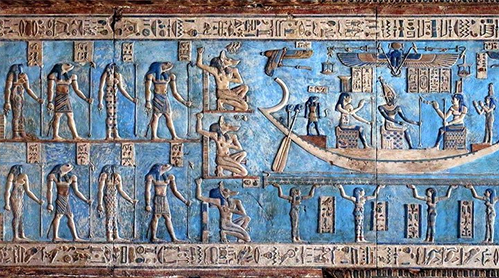

The religion of the Egyptians was a multifarious system of polytheistic beliefs and rituals which were an important part of the ancient Egyptian culture. The Egyptians believed that their infinite deities were in control of the forces of nature. They prayed, and presented offerings to their gods in the hope of gaining their favors. The formal religious practice was centered on the pharaoh, the king of Egypt, who was believed to possess a divine power by virtue of his position. He functioned as an intermediary between the people and the gods and was obligated to appease the gods through offerings and rituals so that they maintained order in the universe. Therefore, the state allocated vast resources for Egyptian religious practices and for the construction of temples. Even though prophets did come to this empire to guide the people towards the right path, very few people paid heed to their message and most remain misguided for centuries to come and lost everything in this world and the hereafter.

The idiosyncratic features of Ancient Egyptian culture were its inclusiveness, adaptation to change, and apparently paradoxical conservatism. These characteristics combined to create one of the longest-running religions of humankind. The earliest religious beliefs of the Egyptians are unclear, 1 but it is clear that religion was an integral part of the lives of the ancient Egyptians and permeated most aspects of everyday existence in addition to laying the foundation for their funerary beliefs and customs. Religion was practiced at the state level with the king acting as the unique link between the gods and men, and the temples played an important role in this respect too. There are rare evidences of personal piety and worship by ordinary people who prayed to special deities in their own homes.

Over the course of Egyptian history, Egyptians worshipped more than 2,000 gods and goddesses, 2 which they thought to be present in the heaven and below the earth. To some of the Egyptians, heaven was an immense and friendly cow standing over them, upheld by their false gods, and with the morning boat of the sun sailing under her star-sprangled belly. While others had a more imprudent belief that the heaven was a woman, bending over the earth, with an excessively elongated body, upheld by a god, and with the sun as a beetle, or a winged disk, or simply a disk under her body and legs. 3

Every town and village had its local patrons. Every month of the year every day of the month, every hour of the day and night, had its presiding divinity and all these gods had to be propitiated by offerings. 4 When a city became important, so did its gods and goddesses. Egyptians were more likely to adopt foreign gods than to persecute their worshippers. They were essentially worshippers of power. Whenever they found any city or nation flourishing materialistically, they adopted their gods as their own and started praying to them. They had many views about the universe and several illogical creation stories. The fact that all these views and stories were not exactly the same and did not even bother them at all. According to James Henry Breasted their religion was magical, not logical. 5

As among all other early people, it was in their natural surroundings that the Egyptians first saw their gods. The trees and springs, the stones and hill-tops, the birds and beasts, were creatures like themselves, but possessed of strange uncanny powers of which they were not master. Nature thus made the earliest impression upon the religious faculty. 6

Early Animal Cults

Before the unification (3100 B.C.) it seems that there were many localized and unconnected cults, and each community worshiped its own deity. Most were originally represented in animal or fetish form, and the importance of animal cults in later times is already emphasized in these early societies. There were animal burials in some villages in which dogs or jackals, sheep, and cows were wrapped in linen and matting and interred among human burials. Amulets in the form of animals were placed with human burials to provide protection and a food supply for the deceased, while animal gods were presented on the painted pottery of the Nagada II period. There were also animal statuettes and slate palettes in the form of animals in many of the early graves. The reasons behind the deification of animals in ancient Egypt are not clear: possibly some were worshiped because they assisted mankind, while others, who were feared (such as the jackals who ransacked the cemeteries), were deified in an attempt to propitiate them. Strangely, they never tried to figure out about the reality of God who created all these mortals and the earth with all its resources so that it was able to sustain itself.

It is evident, however, that animal and fetish forms were regarded as symbols through which the divine power could manifest itself and that animal worship continued to be extremely important throughout the historic period. A few of the gods, such as Ptah the creator god of Memphis, were always represented with a full human form, but most retained some animal characteristics. In the early dynastic period, there was a gradual anthropomorphization of the animal gods, who began to be represented with animal or bird heads on human bodies. By Dynasty 2, some animal gods appear with fully human forms. Throughout the historic period, however, animal deities continue to display a variety of forms; some have complete animal bodies, some have animal heads and human bodies, and few take on a completely human appearance. 7

Regarding animal worship in ancient Egypt, W. M. Flinders Petrie states:

“Of sacred animals we find thirty-one, of which seven are serpents. Four views of animal worship are now held. Some regard the animals as having been first worshipped for their powers and unexplained actions, simply as fellow beings with man. Another view is that they were worshipped as exemplifying certain characteristics of power, fertility, cunning etc. The third view is that they were only sacred to the gods and that they were not directly worshipped. A fourth view is that they were worshipped due to their utility though it is not solid since the animals worshipped were not of any use to men.” 8

Cosmic Gods

During the Pre-dynastic Period a group of deities emerged whom Egyptologists now term cosmic gods. They differed in several respects from the local, tribal gods, and it has been suggested that they may have been introduced into Egypt from another area. Although many of the older tribal gods survived virtually unchanged, some may have been fused with the cosmic deities so that the latter could adopt some of their characteristics and take over their cult centers. Cosmic and local gods continued to be worshiped throughout the historic period, with the cosmic deities usually assuming roles as state gods.

The Pantheon

As political development occurred in pre-dynastic times and the villages got united to become clans and eventually districts (nomes), the gods of each community were amalgamated and transformed from local deities into gods of the nomes. In this process called syncretism, deities of conquered or subordinated areas would be absorbed into the god of the victorious community. Any desirable features or characteristics of the conquered deities would be assimilated by the victorious god to enhance his own powers, or sometimes they would become assistants or followers of the god or would cease to exist. The chief god of a nome provided the regional chieftain with protection and had extensive powers; he would be represented by the ensign of the nome. This amalgamation of local cults that had followed the political pattern resulted, by the Old Kingdom, in an expanded and confusing pantheon.

In practice each individual probably worshiped only one local god or group of gods. Nevertheless, there was such confusion by the Old Kingdom that the priesthood attempted to organize the gods in the pantheon either into family groups or into ogdoads 9 or enneads (group of nine gods) according to their direct associations with particular cult centers. Creation myths (cosmogonies) and other mythologies were developed to emphasize the relationships between the deities of each group or family. A pantheon of gods thus emerged and continued throughout the historic period. Some retained only local or limited significance, although they had cults and were worshiped in temples.

Sometimes a particular line of rulers would elevate their own local god to become the dynasty’s royal patron, with the deity acquiring, if only temporarily, the status of a state god. Nevertheless, most state gods continued to hold their place in the top league of deities throughout many centuries. Their powers extended throughout Egypt even if they had particular associations with certain cities and cult centers. They received cultic worship in the temples and were believed to influence the power and success of the nation in internal affairs and in foreign conquests. The divine patron and protector of each line of rulers was one of the state gods, and he became the supreme deity of that dynasty. Some, such as Re, the sun god, Osiris the god of the dead, Isis the wife of Osiris, and Amun the king of the gods, achieved almost continuous and even international acclaim and worship as supreme deities.

Myth of Kingship

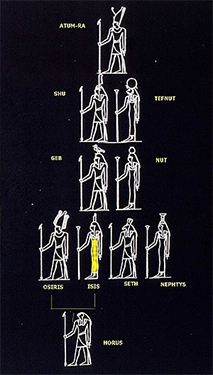

Along with this great pantheon, or group of gods worshipped by society, the early Egyptians held a belief that their pharaoh had a divine spark. Historians think that this belief faded overtime and is rejected by the majority because of the immoral character of their ruling class. This idea came from one of the most important and revered of the country’s religious tales, today called the Myth of Kingship.

In this story, the grownup Horus fought and defeated his uncle—Osiris’s and Isis’s brother Seth (or Set). Horus then took the throne as Egypt’s first pharaoh. More significantly, thereafter each pharaoh carried a part of Horus’s spirit, so that he was the divine Horus as long as he lived and ruled. After a pharaoh died, however, he became one with Horus’s father, Osiris, ruler of the kingdom of the dead.

Belief in the Myth of Kingship strongly affected religious rituals and customs in Egypt. “Each king,” says Ian Shaw, came to be seen “as a combination of the divine and the mortal in the same way that the living king was linked with Horus, and the dead kings, the royal ancestors, were associated with Horus’s father Osiris.” Therefore, the living pharaoh received worship, including offerings of prayer and gifts, and so did the past pharaohs. Special temples were erected for them in which priests conducted rituals intended to make sure those rulers prospered in the afterlife. 10

Gods and Goddesses

There were hundreds of deities in the Egyptian pantheon with whom many unethical characteristics were associated, which are even not acceptable for a common pious man or woman of any religion. Egyptian gods were commonly allied with those humanly traits which can only be found in those societies where religion did not exist practically. Here is the list of gods represented in three main categories, mentioned by Rosalie David i.e. state, local, and household gods 11 in a brief manner to understand the blotches in their beliefs:

State Gods

AtumThe name ‘Atum’, carries the idea of ‘totality’ in the sense of an ultimate and unalterable state of perfection. Atum was frequently called ‘Lord of Heliopolis’ (‘Iunu’ in Egyptian), the major center of sun worship.

As early as the Pyramid Era there were unethical and baseless references to the creation of gods of the elements by Atum which are not only immodest in nature but are ridiculous to be discussed. It is said that arising self-engendered out of the primeval water, Atum took his phallus in his hand and brought it to orgasm. This hand performing, the vital act of creation, can figure in the hieroglyphs writing the god’s name and is also the original source of the title ‘God’s Hand’ adopted for the Theban priestess regarded as symbolically married to Amun. The semen of Atum then produced the first two divinities in his cosmos, Shu and Tefnut. These became the parents and grandparents of the remaining deities that form Atum’s Ennead (or company of nine gods) at Heliopolis. A coeval but variant explanation of the means by which Atum created his offspring was based on the similarity of the sound of the names of Shu and Tefnut to the words for to spit and expectorate, the two deities being envisaged as arising from Atum’s mucus. 12

Shu and Tefnut carried on the cycle, and from their union a son Geb (the earth god) and daughter Nut (the sky goddess) were born; their arrival completed all the cosmic elements necessary for creation (light, air, moisture, earth, and heaven). Geb and Nut in turn became the parents of two sons, Osiris and Seth, and two daughters, Isis and Nephthys, who were not cosmic deities. These gods made up the Heliopolitan Ennead (group of nine gods); this Heliopolitan cosmogony was the most famous of the creation myths. Osiris married Isis, and Seth became the husband of Nephthys; the mythology surrounding Osiris’s family is one of the greatest religious sources from ancient Egypt. 13

Atum was called the father of the king of Egypt, intensifying the link between the sun-god as Ra and the monarchy which is of paramount importance from at least Dynasty IV. Thus, the paternal protection of Atum was sought from the pyramid in which the king was buried. In the Afterlife Atum embraced his son, the dead monarch, raising him into the sky as head of the star-gods. By using magic formulae, the king might even hope to surpass the power of Atum, becoming himself the supreme deity and rule as Atum over every god. Through this polarization of the king the royal flesh itself became a manifestation of Atum. In the political sphere it is essential for Atum to be seen participating in the coronation ritual of the pharaoh. For instance, in the temple of Amun at Karnak reliefs show Atum together with Montu, two gods of North and South Egypt respectively, conducting the king into the sacred precinct. The underlying message is that Atum as creator-god is the ultimate source of pharaonic power: it was after all to Horus (of whom the king of Egypt was the living manifestation), belonging to the fifth generation of Atum’s family, that the throne of Egypt was awarded. Atum’s omnipotence quelled hostile forces in the Underworld. He overcame the dangerous snake Nehebu-kau by pressing his fingernail on its spine. Before Gate 9 of the Underworld, Atum stood confronting the coiled serpent Apophis condemning him to be overthrown and annihilated. It was Atum who offered protection to the deceased on his journey through the Underworld to paradise, ensuring a safe passage past the Lake of Fire where there lurked a deadly dog-headed god who lived by swallowing souls and snatching hearts. 14

Osiris

Osiris was called the son of the god of earth and the goddess of heaven. According to their belief, he was the first king who ruled Egypt in human fashion; he showed his divine nature by his graciousness and beneficence. 15 In fuller iconography his body was portrayed as wrapped in mummy bandages from which his arms emerged to hold the scepters of kingship – the crook and the flail. His distinctive crown was known as the ‘Atef’ comprises a ram’s horns at its base, and a tall conical centerpiece sporting a plume on each side.

Although Osiris was one of the greatest gods, the Myth of Osiris is preserved completely only in Plutarch’s writings, De Iside et Osiride. This relates how Osiris was an early human king who ruled Egypt and brought civilization and agriculture to the people. Murdered by his jealous brother Seth, Osiris’s body was dismembered and scattered throughout Egypt. Isis (his sister-wife), however, gathered together and magically reunited his limbs and then posthumously conceived Osiris’s son Horus. When grown, Horus sought to avenge his father’s death by fighting Seth in a bloody conflict. Eventually their dispute was brought before the tribunal of gods whose judgment favored Osiris and Horus. Osiris was resurrected and continued his existence in the underworld where he became king and judge of the dead, while Horus became king of the living; Seth, now identified as the “Evil One,” was banished.

In the Middle Kingdom the cult of Osiris became widespread and important; it offered resurrection and eternal life to followers who had lived according to the rules and emphasized that morality rather than wealth ensured immortality. The two great cult centers of Osiris were Busiris and Abydos, which became a place of pilgrimage. The cult of Osiris had a profound effect on religious belief and practices, and the triad of Osiris, Isis, and Horus became a symbol of family virtues. Osiris and Horus were also directly associated with the concept of kingship, and Isis became the supreme mother goddess.

Gods of Memphis

The Egyptians had several man-made beliefs about their gods which were quite illogical and sometimes even ridiculous in nature. According to the Memphite creation myth, Ptah was the creator of the universe and the master of destiny. 16 Also spelled as Phthah, whom the Greeks identified with their Hephaistos, and the Romans with their Vulcan. He was an artisan god, the actual manipulator of matter, and creator of the sun, the moon, and the earth. He was called, the father of the beginnings, the first of the gods of the upper world, he who adjusted the world by his hands, the lord of the beautiful countenance, and the lord of truth. 17 He was one of the oldest of ancient Egypt’s gods, and was the main deity of Memphis. Consequently, Memphis was sometimes called Hiku-Ptah or Hat-Ka-Ptah, which translated as the “Palace of the Soul of Ptah.” However, Ptah was typically worshiped in conjunction with his consort, the goddess Sekhmet, and their son, the god Nefertem. Ptah was said to have directly made all life. All deities, towns, people, animals, and everything else in existence was first formed within his heart; he spoke their names to call them into being. He created not only all inanimate objects and living things but also personified concepts such as Truth and Order. Ptah was typically depicted as a semi-mummified man carrying a staff with three important Egyptian symbols: the ‘was’ (a staff with an animal head), the ‘djed’ (a pillar with three horizontal lines at the top), and the ankh (shaped like a capital letter “T” with an inverted teardrop atop it), representing power, stability, and life, respectively.

Ptah was also associated with architecture, undoubtedly because in his role as creator he produced all buildings. In addition, Ptah was honored as the source of creativity, no matter what form it is. Beginning in the Old Kingdom, Ptah might appear as Ptah-Sokar, incorporating Ptah’s characteristics with those of the god Sokar, who personified the darkest parts of the Underworld. The main role of this composite god was as the guardian of Memphis tombs. During the Late Period, Ptah usually appeared as Ptah-Sokar-Osiris, placing even more emphasis on the god’s funerary aspects in a way that Egyptologists do not quite understand, although they do know that beliefs related to Ptah-Sokar-Osiris involved the concept of resurrection. 18

Theban Triad

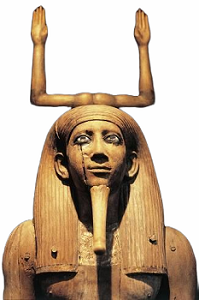

Amun, chief god of Thebes, was originally one of the eight gods of Hermopolis. His cult increased in importance at Thebes from Dynasty 12, when a temple was built there for his worship. In Dynasty 18, when a family of Theban princes became kings of Egypt, Amun’s cult reached unprecedented status. He became associated with and absorbed the characteristics of Re of Heliopolis to form the deity Amen-Re.

Although briefly eclipsed as supreme state god by the Aten toward the end of Dynasty 18, Amun was soon reinstated as the great royal deity who was “Father of the Gods” and ruler of Egypt and the people of its empire. The conflict between the status and power of the king and of Amun was never resolved. Amun’s consort Mut had an important center (the Temple of Luxor) near Amun’s great complex at Karnak. 19 Mut was an Egyptian goddess whose body formed the sky, although she was believed to manifest on earth sometimes as a vulture. 20 Her iconography is predominantly anthropomorphic: a slim lady in a linen dress, often brightly colored blue or red in a pattern suggesting feathers, wearing a head-dress in the shape of a vulture surmounted by the combined crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt. She holds the lily scepter of the south. 21 She is also believed to be the mother of Khons. Khons, also spelled Khonsu or Chons, in ancient Egyptian religion, is the moon god who was generally depicted as a youth. A deity with astronomical associations named Khenzu is known from the Pyramid Texts (c. 2350 B.C.) and is possibly the same as Khons. In the period of the late New Kingdom (c. 1100 B.C.), a major temple was built for Khons in the Karnak complex at Thebes. Khons was generally depicted as a young man with a side lock of hair; on his head he wore a uraeus (rearing cobra) and a lunar disk. Khons also was associated with baboons and was sometimes assimilated to Thoth, another moon god associated with baboons. 22

Cult of Aten

In the reign of Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten), the cult of the Aten (“sun’s disk”) or Aton became a form of so-called monotheism; the temples of other gods were closed down and their priests were disbanded. 23 The origin of this god was wholly obscure, and nearly all that is known about him under the Middle Empire is that he was some small provincial form of the Sun-god who was worshipped in one of the little towns in the neighborhood of Heliopolis, and it is possible that a temple was built in his honor in Heliopolis itself. 24 All other gods were abandoned because of him and he took the ultimate place. No one thought that if the other deities were indeed gods then how come they were defeated. Secondly if this so-called monotheism really involved worship of a single real god then why was his appearance so late? The only reason was that the normal people simply followed what the king told them.

The only people who knew and comprehended the god were said to be Akhenaton together with his wife, Nefertiti. The hymn to the Aton has been compared in imagery to Psalm 104 (“Bless the Lord, O my soul”). Akhenaton devoted himself to the worship of the Aton, erasing all images of Amon and all writings of his name and sometimes even writings containing the word gods. But the new religion was rejected by the Egyptian elite after Akhenaton’s death, and the populace had probably never adopted it in the first place. After Akhenaton’s death, the old gods were re-established and the new city abandoned. Aton worship was not fully monotheistic (because the pharaoh himself was considered a god), nor was it a direct precursor of monotheistic religions such as Judaism or Islam. 25 Actually, they all were confused. They were very weak in their beliefs and were the followers of the powerful and materially sound personalities. They never had any strong spiritual bindings with their gods and, how could they? When they all were man-made and were merely pieces of bricks, mud or gold.

Local gods

Some gods retained only a local importance and were worshipped in temples at particular sites. Sobek, the crocodile god, was a form of Seth and had temples at various places, but particularly in the Fayum and at Kom Ombo. Montu, the falcon-headed god of war, was worshiped at Armant, but in Dynasty 11 he was elevated to become the protector of the royal line that originated there. These are the two famous examples of a wide range of local gods.

Household gods

Some deities did not receive temple cults because of their weaknesses and unacceptability in the general society but nevertheless played a part in comforting people of some classes. They were worshiped at shrines in the home. The best known are Bes and his consort Tauert. Bes, represented as an ugly dwarf wearing a feathered crown, protected children and women in childbirth; he was the god of marriage and jollification. Tauert, shown as a pregnant female hippopotamus, was a symbol of fecundity and assisted all females (divine, royal, or ordinary) in childbirth. 26 These gods were unable to do any major work according to people’s beliefs but were still considered as ‘gods’ in the Egyptian society which is enough to understand that their religious system was flawed.

Other gods

HapiOsiris was probably in pre-dynastic times a river-god, or a water-god, and that in course of time he became identified with Hap, or Hapi, the god of the Nile. Hap, was a very ancient name for the Nile and Nile-god, and it is probably the name which was given to the river by the pre-dynastic inhabitants of Egypt.

This god was always depicted in the form of a man, but his breasts were those of a woman, and they are intended to indicate the powers of fertility and of nourishment possessed by the god. 27 The god holds before him an offering tray full of the products resulting from the Nile silt left by the receding waters of the river after the inundation. In the Middle Kingdom the god was ‘master of the river bringing vegetation’. Other epithets for Hapi included ‘lord of the fishes and birds of the marshes’ which might explain the god being given a double-goose head in the temple of Abydos. Crocodile-gods are in his retinue and he possesses a harem of frog-goddesses with braided tresses. Although the flood was the source of the country’s prosperity, no temples or sanctuaries were built specifically in honor of Hapi. But his statues – including some where the pharaoh himself is carved as the god – and reliefs were included in the temples of other deities. An Egyptian hymn to Hapi first mentions that no temple priesthood could commandeer laborers to work on Hapi’s building projects – demands often made in the names of other divinities. 28

Horus

A solar deity, Horus was one of the oldest ancient Egyptian gods, although until the Greek Period he was called Hor. Sometimes the deity was known as Horus the Elder, or Hor-Wer in ancient Egyptian, a force of good battling evil. He was also Horus of Gold, or Hor-Nubti, destroyer of the evil god Seth; Horus of the Horizon, or Harakhtes, a sun god who became part of the solar deity Re as Re-Horakhty; or Harsiesis, or Hor-sa-iset, featured in mythology as the young son of the goddess Isis. In some myths he was considered the son of the goddess Hathor instead. Worshiped as Horus the Behdetite at a shrine in Edfu, he was a falcon god who transformed into a winged sun disk. Elsewhere he was Horus, the Uniter of the Two Lands, or Horu-Sema-Tawy, who after vanquishing the evil god Seth united Egypt with himself as king on earth and the god Osiris as king of the celestial realm. Thus, Egypt’s kings were sometimes called the physical manifestation of Horus while they were living and of Osiris after they died.

From at least as early as the First Dynasty, Horus was associated with Egypt’s kings. At that time, they began using his name as one of their royal titles and his main symbol, the falcon, as the symbol for kingship. Therefore, Horus was often called the protector of the king even though he was also said to be the king. Because of this connection, the king played the part of Horus in certain festivals and rituals. As a major god in the Egyptian pantheon, Horus is the subject of numerous myths. One of these myths—found in the Chester Beatty Papyrus I and dating from the Twentieth Dynasty reign of Ramses V—tells of a dispute between Horus and his uncle, Seth. The two go before the court of the gods, presided over by the god Re, and each argues that he deserves to succeed Osiris as the living king of Egypt. Seth claims this right as the brother of Osiris, even though he was also his murderer, while Horus claims it as Osiris’s son and heir. The gods consider both arguments and begin arguing among themselves, some saying that Seth would make a better king because of his more advanced age and strength and his fierceness; others favor Horus for his goodness and honor and his position as Osiris’s son. After much debate, the gods adjourn without making a decision like a judge of a Court who does not decide the matter due to several emerging confusions. No one ever thought that how could these be gods if they were like humans in their limitations and confinements. True God is the Omnipotent Who is not confined by any boundary and limit and knows everything from the beginning till the end. Unfortunately, the ancient Egyptians were least bothered about knowing their creator because religion had never been their primary issue like the seculars of the modern age who beat about the bushes without understanding the depth of the religion’s philosophy.

However, Horus’s mother Isis then went to Seth disguised as a widow whose son has been cheated out of his inheritance (a herd of cattle). When she told the god her plight, he condemned all those who would steal a son’s position, and upon hearing this the gods sitting in judgment of the case between Horus and Seth award the throne to Horus. Angry over this development, Seth challenges Horus to a contest to determine who will rule, and it quickly turns into a battle. The myth goes on to tell of a series of violent and/or strange contests and battles that ensue before Osiris finally calls out from the Underworld that Horus is his choice for successor. 29

Hathor

Hathor was the supreme goddess of sexual love in Ancient Egypt, immediately identified with Aphrodite by the Greeks when they came into contact with her cult. The turmoil or ecstasy which can result from physical desire is reflected in the conflicting forces of Hathor’s personality as a goddess of destruction as ‘Eye of Ra’ or a goddess of heavenly charm. In love poetry Hathor was called the ‘golden’ or ‘lady of heaven’. Concomitant with her connection with love was her ability to encourage sensual joy by music and dancing. In fact, the child of Hathor and Horus at the temple of Dendera is the god Ihy who really personified musical jubilation. Dances in honor of Hathor were represented on the walls of courtiers’ tombs, and in the story of the return of Sinuhe to the Egyptian court after years abroad, the princesses performed a Hathoric dance to celebrate the occasion.

In the myth of the contest for power between Horus and Seth it is the goddess herself, ‘lady of the southern sycamore’, who cures her father Ra of a fit of sulking by dancing naked in front of him until he bursts into laughter. Music in the cult of Hathor was immensely important and there were two ritual instruments carried by her priestesses to express their joy in worshipping the goddess. 30 Illegal sex and sexual dances have always been a weakness of humans and a major weapon of Satan. These concocted myths were nothing but a mere ploy of the devil to constitutionalize sex and other immoral acts as a part of religion so that humans keep indulging in them and end up destroying their societies and forget their true aim of life which was submitting themselves to the will of God.

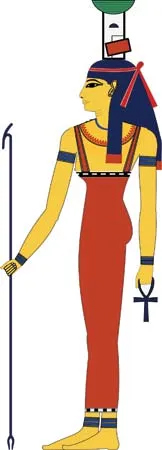

Isis

Isis was an ancient Egyptian goddess, associated with the earlier goddess Hathor, who became the most popular and enduring of all the Egyptian deities. Her name comes from the Egyptian Eset, ("the seat") which referred to her stability and also the throne of Egypt as she was considered the mother of every pharaoh through the king's association with Horus, Isis' son. Her name has also been interpreted as Queen of the Throne, and her original headdress was the empty throne of her murdered husband Osiris. Her symbols were the scorpion (who kept her safe when she was in hiding), the kite (a kind of falcon whose shape she assumed in bringing her husband back to life), the empty throne, and the sistrum. She was regularly portrayed as the selfless, giving, mother, wife, and protectress, who placed other's interests and well-being ahead of her own. She was also known as Weret-Kekau ("the Great Magic") for her power and Mut-Netjer, "Mother of the Gods" but was known by many names depending on which role she was fulfilling at the moment. As the goddess who brought the yearly inundation of the Nile which fertilized the land, she was Sati, for example, and as the goddess who created and preserved life, she was Ankhet, and so on. 31

In Memphis she was said to have given birth to the sacred Apis bull and therefore was depicted as a cow. More commonly, however, the ancient Egyptians depicted Isis as a woman perhaps with a cow’s horns, which was similar to depictions of the mother goddess Hathor. 32

In time, she became so popular that all gods were considered mere aspects of Isis and she was the only Egyptian deity worshiped by everyone in the country. She and her husband and son replaced the Theban Triad of Amon, Mut and Khons who had been the most popular trinity of gods in Egypt. Osiris, Isis, and Horus are referred to as the Abydos Triad. Her cult began in the Nile Delta and her most important sanctuary was there at the shrine of Behbeit El-Hagar, but worship of Isis eventually spread to all parts of Egypt. 33

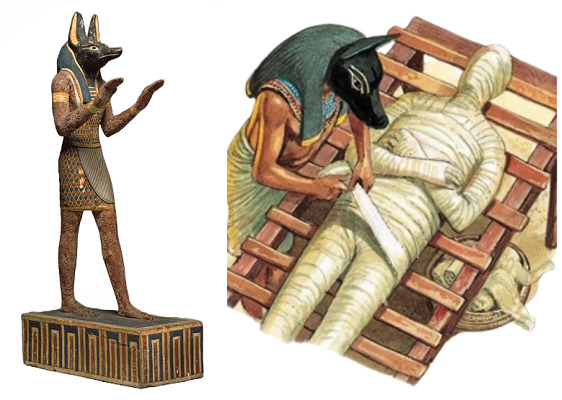

Anubis

The Greek rendering of the Egyptian Anpu or Anup, called the “Opener of the Way” for the dead, Anubis was the guide of the afterlife. From the earliest time Anubis presided over the embalming rituals of the deceased and received many pleas in the mortuary prayers recited on behalf of souls making their way to the Underworld. 34

Also known as the Canine god of the dead, he was closely associated with embalming and mummification. He was usually represented in the form of a seated black dog or a man with a dog's head, but it is not clear whether the dog in question – often identified by the Egyptian word sab - was a jackal. The connection between jackals and the god of mummification probably derived from the desire to ward off the possibility of corpses being dismembered and consumed by such dogs. The black coloring of Anubis, however, was not characteristic of jackals; it was instead related to the color of putrefying corpses and the fertile black soil of the Nile valley (which was closely associated with the concept of rebirth). The seated Anubis dog usually wore a ceremonial tic or collar around his neck and held a flail or sekhem scepter like those held by Osiris, the other principal god of the dead. The cult of Anubis himself was eventually assimilated with that of Osiris. According to the myth, the jackal-god was said to have wrapped the body of the deceased Osiris, thus establishing his particular association with the mummification process. Anubis was also linked with the Imiut fetish, apparently consisting of a decapitated animal skin hanging at the top of a pole, images of which were included among royal funerary equipment in the New Kingdom. Both Anubis and the Imiut fetish were known as 'sons of the hesat-cow'. Anubis' role as the guardian of the necropolis was reflected in two of his most common epithets: lord of the sacred land and foremost of the divine booth, the former showing his control over the cemetery itself and the latter indicating his association with the embalming tent or the burial chamber. An image of Anubis also figured prominently in the seal with which the entrances to the tombs in the Valley of the Kings were stamped. This consisted of an image of a jackal above a set of nine bound captives, showing that Anubis would protect the tomb against evildoers. Perhaps the most vivid of Anubis' titles was 'he who is upon his mountain', which presents the visual image of a god continually keeping a watch on the necropolis from his vantage point in the high desert. In a similar vein, both he and Osiris are regularly described as foremost of the westerners, which indicated their dominance over the necropolis, usually situated in the west. Khentimentiu was originally the name of an earlier canine deity at Abydos whom Anubis superseded. 35

Heka

In the Coffin Texts, Heka is described as coming into being at the beginning of time at the will of the creator god Atum to provide a supernatural strength which would pervade the universe and enable deities and mankind to function. In the Pyramid Texts, Heka was a threatening force and in the spells where the king hunted and devoured gods and men, due to which his own power was increased. The Book of the Dead had spells which emphasized that the deceased will possess the universal magical power of Heka to counteract hazards in the Underworld. Also, one spell was specifically directed against the crocodile trying to steal this magic. In later magical spells Heka was, along with Ra, Thoth and Sakhmet, one of the protectors of Osiris, whose power was invoked to overcome crocodiles by blinding them. Heka was frequently depicted in anthropomorphic form, in the Book of Gates, standing in the boat of the sun-god during his nightly journey through the Netherworld. In the Second Hall, decorated in the Ptolemaic period, of the Mammisi in the Temple of Philae, Heka was the god who proclaimed the enthronement of the son of Isis – and symbolically the pharaoh himself – as ruler of Egypt, holding up the child in his arms. 36

According to the Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Heka was actually portrayed in human frame as a man in illustrious dress wearing the lofty bended facial hair of the divine beings and conveying a staff weaved with two snakes to connect it with the mending god Ninazu of Sumer (child of the goddess Gula). It was embraced for Heka and headed out to Greece where it moved toward becoming related with their recuperating god Asclepius, and today caduceus is the symbol of the medical profession. Heka is sometimes represented as the two divine beings most firmly attached to him, Sia and Hu and, starting in the Late Period (525-332 B.C.), he is also portrayed as a child and, in the meantime, is viewed as the son of Menhet and Khnum as a component of the set of three of Latopolis. 37

Amulets

Funerary equipment was considered to have magical properties that could bring special benefits to the deceased. Amulets formed an important group of jewelry since they acted as lucky charms and could be worn by rich and poor alike. They were carried by the person when alive and placed with the deceased to provide help in his future existence. The term amulet that is applied to this particular type of jewelry comes from the later Arabic word hamulet meaning “something that was borne or carried.” The primary function of all Egyptian jewelry was to protect the wearer against a range of hostile forces and events, which included ferocious animals, disease, famine, accidents, and natural disasters. Amulets were believed to possess special beneficial properties and, by the principles of sympathetic magic, to be able to attract good forces to assist the wearer or, conversely, to repel a variety of evils and dangers. 38

A broad distinction can be made between those amulets that were worn in daily life, in order to protect the bearer magically from the dangers and crises that might threaten him or her, and those made expressly to adorn the mummified body of the deceased. The second category can include funerary deities such as Anubis, Serket, Sons of Horus, but rarely (strangely enough) figures of Osiris, the god of the underworld. 39

Some amulets were regarded as universally beneficial while others had particular significance only for the owner. Essentially, they were charms that had been magically charged in order to bring about the desired results. Some were designed to strengthen the owner’s ability to overcome the dangers he encountered and took the form of images of power such as miniature crowns, scepters, and staffs of office while others represented gods or animals.

Another group was believed to have an impact on any physical weakness or disability from which the owner might suffer; they were modeled to simulate the limbs in the hope that the amulet would attract magical strength to heal the afflicted part or that the disease would be transferred from the limb to the amulet “double”.

The shape of an amulet conferred power and strength on its owner, but some materials and colors were also believed to possess special hidden qualities that could bring health and good luck. Stones such as carnelian, turquoise, and lapis lazuli were much favored because of the magical properties of their colors, and they were often used to manufacture jewelry and amulets. Sometimes stones were selected for amulets if they duplicated the color of the original limb or organ, and this authenticity was expected to bring additional benefits to the owner.

Divine Possessions

The clothes, crowns, jewelry, and insignia that belonged to the god were considered to be especially sacred because of their physical proximity to the divine cult statue in the temple. Similarly, the utensils used to prepare and carry the god’s daily food offerings in the temple rituals had their own magical properties according to their view point. These possessions were kept in special rooms in the temple and were regularly cleansed in the ritually “pure” waters of the temple’s sacred lake.

It was also essential that the priests who came into direct contact with the divine statue and possessions should have be ritually pure, and this was achieved by the observance of special procedures and prohibitions. The god’s crowns were believed to give particular strengths and powers to the deity, and the colors of these and the cloths which were placed on the cult statue each gave him their own protection. 40

Belief in Magic

Magic in ancient Egypt was not a parlor trick or illusion; it was the harnessing of the powers of natural laws, conceived of as supernatural entities, in order to achieve a certain goal. To the Egyptians, a world without magic was inconceivable. They believed that it was through magic that the world had been created, magic sustained the world daily, magic healed when one was sick, gave when one had nothing, and assured one of eternal life after death. The Egyptologist James Henry Breasted has famously remarked how magic infused every aspect of ancient Egyptian life and was "as much a matter of course as sleep or the preparation of food". Magic was present in one's conception, birth, life, death, and afterlife and was represented by a god who was older than creation: Heka. 41

Egyptologist Margaret Bunson describes that few Egyptians could have imagined life without magic because it provided them with a role in godly affairs and an opportunity to become one with the divine. The gods used magic, and the Ankh was the symbol of power that was held in the deities’ hands in reliefs and statues. Magic as a gift from the god Re was to be used for the benefit of all people. Its power allowed the rulers and the priests to act as intermediaries between the world and the supernatural realms.

Three basic elements were always involved in heka: the spell, the ritual, and relevantly, the magic. Spells were traditional but could also evolve and undergo changes during certain eras. They contained words that were viewed as powerful weapons in the hands of the learned of any age. Names were especially potent as magical elements. The Egyptians believed that all things came into existence by being named. The person or object thus vanished when its name was no longer evoked, hence the elaborated mortuary stelae, and the custom of later generations returning to the tombs of their ancestors to recite aloud the names and deeds of each person buried there. Acts of destruction were related to magic, especially in tombs. The damage inflicted on certain hieroglyphic reliefs was designed to remove the magical ability of the objects. Names were struck from inscriptions to prevent their being remembered, thereby denying eternal existence.

In the Old Kingdom tombs (2575–2134 B.C.) the hieroglyphs for animals and humans not buried on the site were frequently destroyed to keep them from resurrecting magically and harming the deceased, especially by devouring the food offerings made daily. Egyptians also hoped to cast spells over enemies with words, gestures, and rites. Amulets were common defenses against Heka as they were believed to defend humans against the curses of foes or supernatural enemies. 42

Religion under the Greeks and the Romans

When Alexander the Great conquered Egypt in 332 B.C., he was welcomed by the people as their savior from the burden of Persian domination and the effects of ineffectual native ruler-ship. The ensuing period of domination by the Ptolemaic Dynasty and then the Roman emperors, however, did little to improve the lives of most Egyptians. During this time Egypt experienced many changes in aspects of its civilization, including religious beliefs and customs. Because of increasing numbers of Greeks settled in Egypt, there was a little attempt to integrate the gods of both peoples although some Greeks eventually adopted some aspects of Egyptian religion. The state, however, attempted to introduce certain cults with the aim of uniting the two peoples. The Ptolemies who established this dynasty were not entirely secure in their claim to rule Egypt; therefore, they established an official dynastic cult to justify their ruler-ship. The earlier Egyptian practice of deifying and worshipping the dead king as one of the royal ancestors now became a cult of the living rulers.

Serapis

Ptolemy I also created a new god, Serapis, to unite the Greeks and Egyptians. 43 The god had a Greek appearance but was given an Egyptian name, and some of his features were based on the Apis bull, an Egyptian deity worshiped at Memphis. Serapis was tolerated by the Egyptians perhaps because of the long association between the Apis and the Egyptian god of the dead, Osiris; similarly, his appearance made Serapis acceptable to the Greeks, and with royal support the cult attracted many adherents. This artificially created cult, however, never achieved any fundamental religious unity between the Greeks and the Egyptians.

Christianity in Egypt

The arrival and spread of Christianity in Egypt brought about profound and irreversible changes in many aspects of the society. Effectively, it drew to a close the ancient religion that had underpinned so many facets of the civilization including writing, literature, architecture, and art.

The Egyptians eagerly adopted Christianity, which reached them as early as the first century A.D., probably entering the country through Alexandria, brought there from Jerusalem by relatives and friends of the Jewish community the new faith promoted ideas such as disinterest in worldly goods and the need for mutual support that found an immediate response among the masses. The poor readily adopted these concepts while the wealthy continued to follow the traditional religions. Initial hostility to Christianity, however, came not from other faiths but from the Romans who regarded it as a subversive movement because it did not acknowledge the divinity of the emperor. Under the Romans there was a systematic persecution of the Christians; Decius in 50 A.D. ordered severe persecution of the Christians at Alexandria, and Septimius Severus’s edict in 204 A.D. prohibited Roman subjects from embracing Christianity. Diocletian was regarded as the instigator of further persecutions in Egypt that occurred around 303 A.D. and lasted for ten years.

These events, nevertheless, only encouraged the Egyptian population to embrace Christianity as an expression of their antagonism toward the Roman state, and by the end of the second century Christian communities were flourishing in Alexandria and Lower Egypt. Constantine I (the son of St. Helena) was the first emperor to give support to Christianity. He stopped the persecutions started under Diocletian and issued the Edict of Toleration in 311 A. D.; further measures were introduced to restore the property of churches and to make public funds available to them. Theodosius I, completed the establishment of Christianity as the empire’s official religion.

Theodosius I was baptized as a Christian soon after his accession, and his edict formally declared Christianity to be the official state religion. He also ordered the closure of temples dedicated to the old deities; there followed a widespread persecution of pagans and heretics and systematic destruction of temples and monuments in Egypt. The last traces of the old faith, however, were only finally removed in the time of Justinian when the temples on the island of Philae were closed. The particular contribution that Egyptian Christianity made to the faith was the idea of physical retreat from the world in search of spiritual values. These ideals were first pursued by hermits who went to live in desert caves and later by religious communities in specially built monasteries. The church in Egypt, however, formed a sect that broke away from the rest of Christendom when, at the Council of Ephesus, the Egyptian clerics rejected the commonly held doctrine that Christ combined a human and divine nature. 44

Concept of Afterlife

The Egyptians believed that the human body was imbued by a special active force, which they called the ka. Every mortal received this ka at birth, if Re commanded it, and as long as he possessed it, so long he is one of the living beings.

When the man died, his ka left him, but it was hoped that it would still concern itself with the body in which it had dwelt so long, and that at any rate it would occasionally re-animate it. And it was probably for the ka that the grave was so carefully attended and provided with food, that it might not hunger or thirst.

In addition to this ka, which always remained a vague and undefined conception, notwithstanding the constant allusions to it, the Egyptians dreamed also of a soul, which might he seen under various forms. At death it left the body and flew away, thus it was naturally a bird, and it was only probable that when the mourners were lamenting their loss, the dead man himself might be close at hand, sitting among the birds on the trees which he himself had planted. The thoughts of others turned to the lotus flowers which had blossomed on the pool during the night, and questioned whether the dead man might not be there; or again to the serpent which crept out of its hole so mysteriously as a son of the earth, or to the crocodile that crawled out of the river on to the bank, as though its true home were the land. 45

By the beginning of the Old Kingdom there was a firm conviction that the king would ascend to the heavens when he died and pass his eternity sailing in the sky in the sacred bark; he would be accompanied in this boat by the gods and he himself would become fully divine, finally joining his father, Re, the sun god. Other Egyptians could only experience a vicarious eternity through the king’s bounty: His family and the nobility were provided with tombs, funerary possessions, and endowments through royal favor; the craftsmen who prepared and decorated the king’s tomb and funerary goods gained immortality through their participation in his burial; and the peasants who labored on his pyramid also hoped for a share in the god king’s eternity.

Middle Kingdom acquainted people with a less rigid idea of this royal celestial hereafter continued for the kings, but now wealthy people and even the peasants anticipated individual resurrection and immortality. Those who could afford to prepare and equip fine tombs hoped to pass at least part of their eternity there, enjoying the benefits provided by the tomb goods. Wall scenes, models of servants, magical inscriptions, and other equipment were all designed to give the tomb owner the opportunity to continue the influential and comfortable lifestyle he had enjoyed in this world.

Special sets of figurines (ushabtis) were even placed in the tombs to relieve the owners of the agricultural labors they would otherwise have to undertake in the underworld. The tomb was regarded as the house of the deceased and included a burial chamber and an offering chapel where the food offerings could be brought by the family or the ka priest. A false door was provided in the tomb structure to allow the deceased’s ka to pass from the burial chamber to partake of the offerings. 46

The people of ancient Egypt, like all the humans of the world were faced with the questions like: What am I? How did I come in to being? How was this earth and the Universe created? etc. but since the human faculties of sense and reasoning, in their very nature were incapable of arriving at an accurate and sure knowledge of the ultimate facts, therefore, the needed the revelations of God through his spiritual luminaries who appeared on the horizon of humanity from time to time. Those spiritual luminaries included men like Adam  , Abraham

, Abraham  , Moses

, Moses  , Jesus

, Jesus  and the last among them, Prophet Muhammad

and the last among them, Prophet Muhammad  . Even though these people had access to the divine teachings over time, still they did not pay heed to it because of their lust for worldly desires. Resultantly, they created their own beliefs about God and the universe which also helped them constitutionalize sex, prostitution, homosexuality, injustice, and other evils so that they could do what everything they liked. Although they believed that they achieved their goals and live a luxurious life, like the people of our age as well, but in reality, they ended up destroying their families, society and failed dismally in this world and the hereafter.

. Even though these people had access to the divine teachings over time, still they did not pay heed to it because of their lust for worldly desires. Resultantly, they created their own beliefs about God and the universe which also helped them constitutionalize sex, prostitution, homosexuality, injustice, and other evils so that they could do what everything they liked. Although they believed that they achieved their goals and live a luxurious life, like the people of our age as well, but in reality, they ended up destroying their families, society and failed dismally in this world and the hereafter.

- 1 Allan B. Lloyd (2010), A Companion to Ancient Egypt, Blackwell Publishing, Sussex, U.K., Vol. 1, Pg. 507.

- 2 Wendy Christensen (2009), Empire of Ancient Egypt, Chelsea House Publishers, New York, USA, Pg. 109.

- 3 Samuel A. B. Mercer (1949), The Religion of Ancient Egypt, Luzac & Co. Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 21.

- 4 P. Le. Page Renouf (1879), The Hibbert Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion of Ancient Egypt, Williams & Norgate, London, U.K., Pg. 85-86.

- 5 Wendy Christensen (2009), Empire of Ancient Egypt, Chelsea House Publishers, New York, USA, Pg. 109.

- 6 James Henry Breasted (1912), Development of Religion and thought in Ancient Egypt, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, USA, Pg. 4.

- 7 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 150.

- 8 W. M. Flinders Petrie (1898), Religion and Conscience in Ancient Egypt, Methuen & Co., London, U.K., Pg. 71-72.

- 9 A group of eight divine beings. [Meriam Webster (Online Version):https://www.merriamwebster.com/dictio nary/Ogdoad : Retrieved: 25-04-2019

- 10 Don Nardo (2015), Life in Ancient Egypt, Reference Point Press, San Diego, California, USA, Pg. 73-74.

- 11 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 150-151.

- 12 George Hart (2005), The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, Routledge, New York, USA, Pg. 40-41.

- 13 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 152.

- 14 George Hart (2005), The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, Routledge, New York, USA, Pg. 41-42.

- 15 A. Wiedemann (1902), The Ancient East: The Realms of the Egyptian Dead (Translated by J. Hutchison), David Nutt, London, U.K., Pg. 35.

- 16 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 152.

- 17 George Rawlinson (1883), Religions of the Ancient World, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, USA, Pg. 12-13.

- 18 Patricia D. Netzley (2003), The Green Haven Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Green Haven Press, Michigan, USA, Pg. 241.

- 19 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 153.

- 20 Patricia D. Netzley (2003), The Green Haven Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Green Haven Press, Michigan, USA, Pg. 205.

- 21 George Hart (2005), The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, Routledge, New York, USA, Pg. 97.

- 22 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version):https://www.britannica.com/topic/Khons : Retrieved: 06-06-17

- 23 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 153.

- 24 E. A. Wallis Budge (1904), The Gods of the Egyptians, The Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 68.

- 25 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/topic/Aton : Retrieved: 06-06-17

- 26 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 154.

- 27 E. A. Wallis SBudge (1904), The Gods of The Egyptians, The Open Court Publishing Company, Chicago, USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 42-43.

- 28 George Hart (2005), The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, New York, USA, Pg. 61.

- 29 Patricia D. Netzley (2003), The Green Haven Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Green Haven Press, Michigan, USA, Pg. 147-148.

- 30 George Hart (2005), The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, Routledge, New York, USA, Pg. 64-65.

- 31 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version) :http://www.ancient.eu/isis/ : Retrieved: 06-06-17

- 32 Patricia D. Netzley (2003), The Green Haven Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Green Haven Press, Michigan, USA, Pg. 156-157.

- 33 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version) : http://www.ancient.eu/isis/ : Retrieved: 06-06-17

- 34 Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 42.

- 35 Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson (2002), The British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, Egypt, Pg. 34-35.

- 36 George Hart (2005), The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, New York, USA, Pg. 67.

- 37 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online):https://www.ancient.eu/Heka/ : Retrieved: 23-02-19

- 38 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 163.

- 39 Ian Shaw and Paul Nicholson (2002), The British Museum Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, The American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, Egypt, Pg. 30.

- 40 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 163-164.

- 41 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): http://www.ancient.eu/article/1019/ : Retrieved: 07-06-17

- 42 Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 223-224.

- 43 Ann M. Nicgorski, The Fate of Serapis: A Paradigm for Transformations in the Culture and Art of Late Roman Egypt, Williamete University, Oregon, USA, Pg. 154.

- 44 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 179-182.

- 45 Adolf Erman (1908), A Handbook of Egyptian Religion (Translated by A. S. Griffith), Archibald Constable & Co. Ltd., London, U.K, Pg. 86-87.

- 46 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 188.