History of Ancient Egypt – Civilization, Dynasties & Legacy

Published on: 06-Jul-2024(Cite: Hamdani, Mufti Shah Rafi Uddin & Khan, Dr. (Mufti) Imran. (2020), History of Ancient Egypt, Encyclopedia of Muhammad  , Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 449-471.)

, Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 449-471.)

Ancient Egypt was one of those ancient civilizations which rose independently. This civilization was located in northeastern Africa and dates back to the 3rd millennium. Its achievements are generally preserved in the artifacts and monuments which are being discovered till date. These artifacts hold a kind of fascination that continues to grow as archaeological findings expose its secrets.

Egypt was the nation called “the gift of the Nile” and evolved in isolation on the northeastern section of the African continent. The name Egypt is the modern version of Aigyptos, the Greek word derived from the Egyptian for the city of Memphis, Hiku Ptah, the “Mansion of the Soul, or ka, of Ptah.” Egyptians call their land Msr (مِصر) today, and in Pharaonic times it was designated Khem or Khemet. 1

Egypt was ancient even to the ancients. It was an independent nation, a thousand years before the Minoans of Crete built their palace at Knossos, about 900 years before the Israelites followed Moses  out of bondage. It flourished when tribesmen still dwelt in huts above the Tiber. Greeks and Romans viewed it in somewhat the same way, 2000 years ago, as the ruins of Greece and Rome are viewed by modern man.

out of bondage. It flourished when tribesmen still dwelt in huts above the Tiber. Greeks and Romans viewed it in somewhat the same way, 2000 years ago, as the ruins of Greece and Rome are viewed by modern man.

The Historian Herodotus made a grand tour of ancient Egypt in the 5th century B.C. and wrote about wonders and works that were beyond expression. Later writers bore him out. Journeying the Nile, they passed the imposing mounds of the pyramids, avenues of sphinxes, slender obelisks. They were dwarfed by towering images in stone and intrigued by enigmatic hieroglyphics covering the walls of the temples.

For one thing, Egypt was one of the earliest of the ancient lands to weave the threads of civilization into a truly impressive culture. More to the point, it sustained its achievements unabated for more than two and a half millennia—a span of accomplishment with few equals in the saga of humanity. 2 However, despite having such accomplished and learned minds, the intelligentsia of this civilization was unable to unearth the reality of their creator and the aim of their lives.

Geography

Every civilization reflects, to some degree, the influence of its environment. Egypt was a country where, the physical and natural features provided a dramatic and contrasting setting for human events. 3 Egypt had always been a narrow, fertile strip of land along the Nile River surrounded by deserts, called the Red Lands, or Deshret. The northern border was the Mediterranean Sea, called the Uat-ur or Wadj-ur, the “Great Green.” The southern border was the first cataract at Aswan until the Middle Kingdom (2040–1640 B.C.), although the armies of the Early Dynastic Period (2920–2575 B.C.) and Old Kingdom (2575–2134 B.C.) conducted trading and punitive expeditions and even erected fortified settlements and centers to the south of Aswan. During the Middle Kingdom the southern border was extended some 250 miles, and in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.) the southern outpost was some 600 miles south of Aswan.

Egypt was composed of the Nile Valley, the Delta, the Fayum, and the eastern (Arabian or Red Sea) desert. The Libyan Desert served as the border on the west. Traditionally there has been another geographic duality in Egypt: The Upper and Lower Kingdoms, now called Upper and Lower Egypt.

Lower Egypt, located in the north and called Ta-Meht, is believed to have encompassed the land from the Mediterranean Sea to Itj-Tawy (Lisht) or possibly to Assiut. There is evidence that Lower Egypt was not actually a kingdom when the armies of the south came to dominate the region and to bring about a unified nation (3000 B.C.). A depiction of a ruler can be seen on a major historical source from the period, but no events or details are provided. The only rulers listed by name from the late Pre-dynastic age (before 3000 B.C.) are from the south. The concept of Lower Egypt starting as a kingdom with its own geographical and social uniqueness quite probably was a fabrication with religious and political overtones. The Egyptians grasped a great sense of symmetry, and the idea of two parallel geographical units united to form one great nation would have appealed to them.

It is not certain that there was any sort of provincial designation in the northern lands in the Pre-dynastic Period either. The nomes, 4 date to the first dynasties, and it is possible that Lower Egypt was not one unified region at all. Whether a confederation of small groups or a people under the command of a single king, Lower Egypt called the city of Buto its capital (Pe in Egyptian), then Sais. Lower Egypt was always dominated by the Delta, originally formed by perennial swamps and lakes. It turned into seasonally flooded basins as the climate stabilized and inhabitants left an impact on the region. Originally as many as seven river branches wound through this area, and the annual inundation of the Nile deposited layers of effluvium and silt. There was continued moisture, gentle winds, and a vastness that encouraged agriculture.

Upper Egypt, the territory south of Itj-tawy to the first cataract of the Nile at Aswan, was called Ta-resu. It is possible that the southern border of Egypt was originally north of Aswan, as the rulers of the First Dynasty added territory to the nation. It is also possible that Upper Egypt included some lands south of Aswan in pre-dynastic times. The Nile Valley dominated Upper Egypt, which had sandstone cliffs and massive outcroppings of granite. These cliffs marched alongside the Nile, sometimes set back from the shore and sometimes coming close to the river’s edge. There were river terraces, however, and areas of continued moisture, as the remains of trees and vegetation indicate that the region was once less arid. The original settlers of the region started their sites on the edges of the desert to secure themselves from the floods. There were probably rudimentary forms of provincial government in Upper Egypt as well, specific multifamily groups that had consolidated their holdings. Totems of some of these groups or provincial units are evident in the unification documentation. The nomes, or provinces, were established originally by the rulers of the first dynasties or perhaps were in existence in earlier eras. It is probable that Upper Egypt was advanced in that regard. 5

Climate

Ancient Egyptian landscapes were also viewed through the lens of climate change. This affected ancient Egyptian landscapes far more broadly than the Nile, although the changes are far less easy to view. One might associate climate change with only the start of ancient Egyptian civilization, 3000 B.C., but determining exactly how the civilization started means going back even further in time. Earliest remains (from the Neolithic Period) were buried beneath many meters of silt in the Nile Valley, while many other settlements remain to be discovered.

A cooling period of 9 degrees Celsius had been noted across East Africa and South-east Asia 9000 B.C., with many sand dunes advancing south. Populations would have moved into the Nile Valley owing to the increasing aridity of the Sahara, which would have caused lakes or streams next to seasonal campsites to dry out. This is noted, in particular, in the Fayum, where archaeologists have discovered hundreds of campsites dating to 9000–6000 B.C. Domesticated sheep and barley have been noted around 8,000 years ago, during the Epipaleolithic 6 period. The climate shift caused a cultural response, with changes noted in stone tools and pottery. During the Neolithic Period, people living along the Nile Valley cultivated wheat and barley, as well as tending to their flocks of domesticated cattle and sheep. For the first time, farmers altered their landscapes with building dykes and irrigation ditches. It is not known if the cultivated crops came from Southeast Asia via trade or via immigration

During the Pre-dynastic period climatic conditions allowed Egyptian civilization to develop. The ancient city of Hierakonpolis represented an ideal habitat owing to good Nile flood levels, fertile soil, nearby raw materials in the Eastern Desert, the proximity of a (now defunct) Nile channel, and an easily established irrigation system.

A stable climate led to broad growth in all aspects of Old Kingdom society and culture, which led to a search for raw materials and products abroad. Higher Nile floods were noted during the Middle Kingdom by late Twelfth Dynasty inscriptions, with higher Fayum Lake levels recorded multiple times. Throughout Egyptian history, Nilometers (A structure for measuring Nile River’s clarity and water level during the flood season) recorded years of high and low floods, especially at places such as Elephantine. A period of high floods did not automatically mean a prosperous year: They could, in fact spell disaster if the waters did not recede in time for planting. 7

Emergence of the Egyptian State

Early PeriodThe people of pre-dynastic Egypt were the successors of the Paleolithic inhabitants of northeastern Africa, who had spread over much of its area. During wet phases they had left remains in regions as inhospitable as the Great Sand Sea. The final desiccation of the Sahara was not complete until the end of the 3rd millennium B.C. Over thousands of years people must have migrated from there to the Nile valley, the environment of which improved as the region dried out. In this process the decisive change from the nomadic hunter gatherer way of life of Paleolithic times to settled agriculture has not so far been identified.

Scholars do know that sometime after 5000 B.C. the raising of crops was introduced, probably on a horticultural scale, in small local cultures that seem to have penetrated southward through Egypt into the oases and the Sudan. Several of the basic food plants that were grown are native to the Middle East, so the new techniques probably spread from there. No large-scale migration was required and the cultures were at first largely self-contained. The preserved evidence for them is unrepresentative because it comes from the low desert, where relatively few people lived. As was the case later, most people probably settled in the valley and delta. 8

Pre-Dynastic Period

The Pre-dynastic (4400 B.C.) spans the time from the introduction of farming to the unification of the country under the first king of Dynasty 1 (3050 B.C.). In a sense, it was defined by a set of artificial boundaries created by scholars to distinguish an ill-defined line between the earlier Neolithic and the more complexly organized later Dynastic culture. The boundaries defining this period were artificial in that the developing cultures progressed along a continuum – they were not separated by a single notable event – and some sites classified by archaeologists as Pre-dynastic had strong Neolithic or Early Dynastic aspects. For example, the Early Pre-dynastic Badarian culture still employed Neolithic subsistence methods and Neolithic Merimde had numerous Pre-dynastic characteristics (albeit different from Upper Egypt because of the Delta’s environmental influences). Regardless, the term Pre-dynastic signifies that period when Egyptians developed the cultural vitality and complexity that enabled them to deal as equals with the dazzling civilizations of the Levant and Near East – and later to surpass those cultures. 9 This was the era in which hunters and gatherers abandoned the heights and plateaus to enter the lush Valley of the Nile, discovering safety there and a certain abundance that induced them to begin settlements. These first settlements were not uniform throughout Egypt, and a list of Pre-dynastic cultural sequences has been developed to trace the development of cultural achievements in Upper and Lower Egypt. 10 These two kingdoms, Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt, were the earliest known nations. Their rule probably reached back nearly seven thousand years, that is, Copper-Stone Age nearly to the year 5000 B.C., and lasted for some centuries. 11

Lower Egypt

Fayum (4400–3900 B.C.) was a cultural sequence that emerged on the northern and northeastern shores of an ancient lake in the Fayum district, possibly seasonal in habitation. The site was occupied by agriculturalists, but it is evident that they depended upon fishing and hunting and may have moved with the changes of the yearly migrations of large mammals. Fish were caught with harpoons and beveled points, but the people of this sequence did not use fishhooks.

Mat or reed huts were erected on the sheltered sides of mounds beside fertile grounds. There were underground granaries, removed from the houses to higher ground, to protect the stored materials from flooding. Some evidence has been gathered at these sites to indicate that the people used sheep, goats, and possibly domesticated cattle. The granaries also showed remains of emmer wheat and a form of barley. The stone tools used by the people of Fayum were large, with notches and denticulate. Flints were set into wooden handles, and arrowheads were in use. Baskets were woven for the granaries and for the daily needs, and a variety of rough linen was manufactured. Pottery found in the ancient Egyptian sites was made out of coarse clay, normally in the form of flat dishes and bag-shaped vessels. Some were plain and some had red slip.

The people of this era appear to have lived in microbands, single and extended family groups, with chieftains who provided them with leadership. The sequence indicates the beginning of communities in the north. Merimda (4300–3700 B.C.), a site on the western edge of the Delta, covered a very vast territory with layers of cultural debris that give indications of up to 600 years of habitation. The people of this cultural sequence lived in pole-framed huts, with windbreaks, and some used semi subterranean residences, building the walls high enough to stand above ground. Granaries were composed of clay jars or baskets, buried up to the neck in the ground. The dead of the Merimda sequence were probably buried on the sites, but little evidence of grave goods have been recovered.

El-Omari (3700–3400 B.C.) was a site between modern Cairo and Halwan. The pottery from this sequence was red or black, unadorned, with some vases and some lipped vessels discovered. Flake and blade tools were made, as well as millstones. Oval shelters were constructed, with poles and woven mats, and the people of the El-Omari sites probably had granaries.

Ma'adi (3400–3000 B.C.), was a site located to the northwest of the El-Omari sequence location, contained a large area that was once occupied by the people of this sequence. They constructed oval huts and windbreaks, with wooden posts placed in the ground to support red or wattle walls, sometimes covered with mud. Storage jars and grindstones were discovered beside the houses. There were also two rectangular buildings there, with subterranean chambers, stairs, hearths, and roof poles. Three cemeteries were in use during this sequence, as at Wadi Digla, although the remains of some unborn children were found in the settlement. Animals were also buried there. The Ma’adi sequence people were more sedentary in their lifestyle, probably involved in agriculture and in some herding activities. A copper ax head and the remains of copper ore (the oldest dated find of this nature in Egypt) were also discovered. There is some evidence of Naqada II influences from Upper Egypt, and there are some imported objects from the Palestinian culture on the Mediterranean, probably the result of trade.

Upper Egypt

Badarian (4500–4000 B.C.) was one of the cultural groups living in the Nile region in the areas of el-Hammamiya, el-Matmar, el-Mostagedda, and at the foot of the cliffs at el-Badari. Some Badarian artifacts were also discovered at Erment, Hierankopolis, and in the Wadi Hammamat. A semi-sedentary people, the Badarians lived in tents made of skins, or in huts of reeds hung on poles. They cultivated wheat and barley and collected fruits and herbs, using the castor bean for oil. The people of this sequence wove cloth and used animal skins as furs and as leather. The bones of cattle, sheep, and goats were found on the sites, and domesticated and wild animals were buried in the necropolis areas. Weapons and tools included flint arrowheads, throwing sticks, push planes, and sickle stones. These were found in the gravesites, discovered on the eastern side of the Nile between el-Matmar and el-Etmantieh, located on the edge of the desert. The graves were oval or rectangular and were roofed. Food offerings were placed in the graves, and the corpses were covered with hides or reed matting. Rectangular stone palettes were part of the grave offerings, along with ivory and stone objects. The manufactured pottery of the Badarians demonstrates sophistication and artistry, with semicircular bowls dominating the styles. Vessels used for daily life were smooth or rough brown. The quality pottery was thinner than any other forms manufactured in pre-dynastic times, combed and burnished before firing. Polished red or black, the most unique type was a pottery painted red with a black interior and a lip formed while the vessel was cooling. The tools of the people were bifacial flint knives with cutting edges and rhomboidal knives. Ritual figures, depicting animals and humans, were carved out of ivory or molded in clay. Metal was very rare 12 for the art of mining, was hardly known. As long as men continued to use metal only for making a few copper pins, or beads for the women, or an occasional tiny chisel, metal played an unimportant part in daily life. Stone tools and weapons still continued in common use. 13

Accelerated trade brought advances in the artistic skills of the people of this era, and Palestinian influences are evident in the pottery, which began to include tilted spouts and handles. Copper was evident in weapons and in jewelry, and the people of this sequence used gold foil and silver. Flint blades were sophisticated, and beads and amulets were made out of metals and lapis lazuli. Funerary pottery indicates advanced mortuary cults, and brick houses formed settlements. These small single chambered residences had their own enclosed courtyards. A temple was erected at Hierakonpolis with battered walls. Graves erected in this period were also lined with wooden planks and contained small niches for offerings. Some were built with plastered walls, which were painted.

The cultural sequences discussed above were particular aspects of a growing civilization along the Nile, prompted to cooperate with one another by that great waterway. The Nile, the most vital factor in the lives of the Egyptians, was not always bountiful. It could be a raging source of destruction if allowed to surge uncontrolled. Irrigation projects and diverting projects were necessary to tame the river and to provide water throughout the agricultural seasons. The river, its bounty, and the rich soil it deposited gave birth to a nation. Sometimes, in the late part of the pre-dynastic era, attempts were made by leaders from Upper Egypt to conquer the northern territories. Upper Egypt probably was united by that time, but Lower Egypt’s political condition is not known for certain. Men such as Scorpion and Narmer have been documented, but their individual efforts and their successes have not been determined. There was, however, a renaissance of the arts, a force that would come to flower in the Early Dynastic Period (also called the Archaic Period). 14

The Naqada III phase, 3200-3000 B.C., was the last phase of the Pre-dynastic Period, according to Kaiser's revision of Petrie's sequence dates. It was during this period that Egypt was first unified into a large territorial state, and the political consolidation that laid the foundations for the Early Dynastic state of the 1st and 2nd Dynasties must also have occurred then. 15

Early Dynasties

Also known as the “Archaic”, the Early Dynastic period consists of the 1st and 2nd Dynasties (circa 3050–2686 B.C.). What is now known as “Dynasty 0” should probably be placed in this period as well at the end of the Pre-dynastic sequence. Kings of Dynasty 0, who preceded those of the 1st Dynasty, were buried at Abydos and the names of some of these rulers are known from inscriptions. The Early Dynastic state controlled a vast territory along the Nile from the Delta side to the First Cataract, over 1,000 km along the floodplain. With the 1st Dynasty, the focus of development shifted from south to north, and the early Egyptian state was a centrally controlled polity ruled by a (god) king from the Memphis region. With the Early Dynastic state too, there came the emergence of ancient Egyptian civilization.

In Dynasty 0 and the early 1st Dynasty there is evidence of Egyptian expansion into Lower Nubia and a continued Egyptian presence in the northern Sinai and southern Palestine. The Egyptian presence in southern Palestine did not last through the Early Dynastic period, but with Egyptian penetration in Nubia, the indigenous A-Group culture comes to an end later in the 1st Dynasty. With the unification of Egypt into a large territorial state, the crown most likely wanted to control the trade through Nubia of exotic raw materials used to make luxury goods, which resulted in Egyptian military incursions in Lower Nubia.

In the Memphis region graves and tombs were found beginning in the 1st Dynasty, which suggests the founding of the city at this time. Tombs of high officials are found at nearby North Saqqara, and officials and persons of all levels of status were buried at other sites in the Memphis region. Such burial evidence also suggests that the Memphis region was the administrative center of the state. Other towns must have developed or were founded as administrative centers of the state throughout Egypt. Although it has been suggested that ancient Egypt was a civilization without cities, this was certainly not the case. Most ancient Egyptians in the Early Dynastic period (and all later periods), however, were farmers who lived in small villages. Cereal agriculture was the economic base of the ancient Egyptian state, and by the Early Dynastic period simple basin irrigation may have been practiced which extended land under cultivation and increased yields. Huge agricultural surpluses were possible in this environment, and when such surpluses were controlled by the state, they could support the flowering of Egyptian civilization that is seen in the 1st Dynasty.

From the very beginning of the Dynastic period the institution of kingship was a strong and powerful one. Nowhere else in the ancient Near East at this early date was kingship so important and central to control of the early state. Through ideology and its symbolic material form in tombs, widely held beliefs concerning death came to reflect the hierarchical social organization of the living and the state controlled by the king. This was a politically motivated transformation of the belief system with direct consequences in the socioeconomic system. The king was accorded the most elaborate burial, which was symbolic of his role as mediator between the powers of the netherworld and his deceased subjects, and a belief in an earthly and cosmic order would have provided a certain amount of social cohesiveness for the Early Dynastic state which was quite ridiculous in nature but was very important for them.

All of the 1st Dynasty tombs at Abydos had subsidiary burials in rows around the royal burials, and this is the only time in ancient Egypt when humans were sacrificed for royal burials. Perhaps officials, priests, retainers and women from the royal household were sacrificed to serve their king in the afterlife. The tomb of Djer has the most subsidiary burials, but the later royal burials have fewer. These kings had control over vast resources: craft goods produced in court workshops, goods and materials imported in huge quantities from abroad, and probably conscripted labor that could also be sacrificed for burial with the kings.

The increased use of wood and resin in middle status burials of the 2nd Dynasty probably also points to greatly increased contact and trade with Lebanon. The architecture, art and associated beliefs of the early Old Kingdom clearly evolved from forms of the Early Dynastic period. This was a time of consolidation of the enormous gains of unification—which could easily have failed—when a state bureaucracy was successfully organized and expanded to bring the entire country under its control. This was done through taxation, to support the crown and its projects on a grand scale, which included expeditions for goods and materials to the Sinai, Palestine, Lebanon, Lower Nubia and the Eastern Desert. Conscription must also have been practiced, to build the large royal mortuary monuments and to supply soldiers for military expeditions. The use of early writing no doubt facilitated such state organization. There were obvious rewards to being bureaucrats of the state, as is seen in the early cemeteries on both sides of the river in the Memphis region. In the early Dynasties when the crown began to exert enormous control over land, resources and labor, the ideology of the god-king legitimized such control and became increasingly powerful as a unifying belief system. 16

Old Kingdom

The Old Kingdom was the name given to the period in the 3rd millennium B.C. when Egypt attained its first continuous peak of civilization – the first of three so-called “Kingdom” periods (followed by the Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom) which mark the high points of civilization in the lower Nile Valley.

The Old Kingdom is most commonly regarded as the period from the 3rd Dynasty to the 6th Dynasty (2686–2181 B.C.). Many Egyptologists also include the Memphite 7th and 8th Dynasties in the Old Kingdom as a continuation of the administration centralized at Memphis. While the Old Kingdom was a period of internal security and prosperity, it was followed by a period of disunity and relative cultural decline referred to by Egyptologists as the First Intermediate Period. During the Old Kingdom, the king of Egypt (not called the Pharaoh until the New Kingdom) became a living god who ruled absolutely and could demand the services and wealth of his subjects.

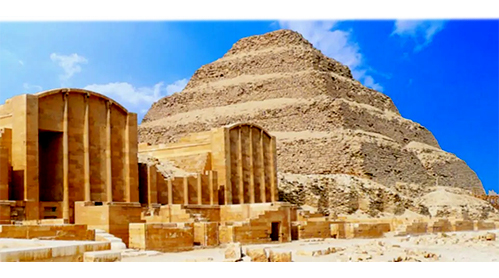

Under King Djoser, the first king of the 3rd Dynasty of the Old Kingdom, the royal capital of Egypt was moved to Memphis, where Djoser established his court. A new era of building was initiated at Saqqara under his reign. King Djoser’s architect, Imhotep is credited with the development of building with stone and with the conception of the new architectural form—the Step Pyramid. Indeed, the Old Kingdom is perhaps best known for the large number of pyramids constructed at this time as burial places for Egypt’s kings. For this reason, the Old Kingdom is frequently referred to as “the Age of the Pyramids”.

First Intermediate Period (2181-2040 B.C.)

A term coined by modern historians, the First Intermediate Period was the era of ancient Egyptian history that followed the collapse of the Old Kingdom, but historians disagree on when it began and what dynasties it incorporated. Some date the First Intermediate Period as being from approximately 2181 to 2040 B.C. and including the 7th, 8th, 9th and 10th Dynasties. Others identify the First Intermediate Period as being from approximately 2160 to 2055 B.C. and including the 9th, 10th and 11th Dynasties. This disparity comes from the fact that historians disagree on when the central government collapsed, ending the unity of the Old Kingdom.

The First Intermediate Period was fraught with disorder as the leaders of various provinces vied for power against weak kings who, beginning in the 9th Dynasty, ruled from the city of Heracleopolis. These provincial leaders, called nomarchs, functioned as warlords, and it was roughly 140 years before they were brought under control by a series of three forceful kings—Intef I, Intef II, and Intef III—who used Thebes as their capital. All three kings were warriors who had forced their way north toward Heracleopolis to challenge the weak kings there, taking various nomes (provinces) along the way and establishing a rival throne. By the time of Intef III, the northern boundary of the Theban kingdom was near Asyut, far north of Thebes though not yet to Heracleopolis. Nonetheless, Intef III’s successor, Montuhotep I or II, was able to mount sustained attacks on Heracleopolis, and eventually he took the city. He subsequently united Egypt under his rule, thereby ushering in the prosperity of the Middle Kingdom. 17

Middle Kingdom

The last ruler of Dynasty 11 was probably assassinated by his vizier, Amenemhe, who seized the throne and became King Amenemhet I, the founder of Dynasty 12. He and his descendants ruled Egypt for the period that Egyptologists have named the Middle Kingdom, when the country flourished again as in the Old Kingdom. They chose a new and more central site for their capital at It-towy, some distance south of Memphis. Thebes was retained as a great religious center. Amenemhet I introduced coregencies (where a monarchial position was held by two or more) to counteract any attempt to place a rival claimant on the throne after his death.

In year 20 of his reign, he made his eldest son (later Senusret I) his coregent, and they ruled together for twenty years. This custom continued throughout the dynasty and ensured a smooth succession even when violent events such as the probable assassination of Amenemhet I occurred. These kings also dealt with the problem of the powerful provincial nobility, which had contributed to the downfall of the Old Kingdom. Under Amenemhet I the nobles retained many privileges and built magnificent rock-cut tombs in their own provinces. Their political and military strength still posed a threat to the king, and a later ruler of Dynasty 12, Senusret III, took decisive action and suppressed these men, removing their rights and privileges and closing their local courts so that they never again challenged royal authority. Their great provincial tombs ceased after his reign, and a new middle class, consisting mainly of craftsmen, tradesmen, and small farmers, replaced the nobles.

The political reorganization of the country was accompanied by an active building program with construction of religious and secular buildings throughout the country. There was also renewed royal interest in foreign policy, which was dictated both by trading and military needs. Trading contacts were renewed with Byblos and Phoenicia, and expeditions were sent to Punt (on the Red Sea coast). During the First Intermediate Period trading and military relations with Nubia had ceased, and a new and more aggressive people had entered Nubia. In Dynasty 12, the Egyptians initiated an active military policy there to reduce the Nubians to submission. An important feature of this was the construction of a series of large brick fortresses along the river between the cataracts. These were intended to present Egypt’s might to the local population and provide a basis for the garrisons to control the waterway and ensure a safe passage for goods brought from Nubia to Egypt. Gold was the main commodity sought, but Nubia was also the source for ebony, ivory, giraffe tails, leopard skins, ostrich feathers, and monkeys.

The kings of Dynasty 12, emphasizing their credentials to rule Egypt, returned to the Old Kingdom tradition of building pyramid complexes, although some new architectural features were introduced. The main cemetery of the capital city It-towy has been identified at the nearby site of el-Lisht, where the pyramids of two kings—Amenemhet I and Senusret I— have been discovered. These kings basically followed the Old Kingdom plan. 18

Second Intermediate Period (1650 B.C.–1550 B.C.)

The Second Intermediate Period was the term conventionally used for the period of divided rule in Egypt after the Middle Kingdom. It began after the end of the 12th Dynasty and ended with the expulsion of the Hyksos from Egypt and the inception of the New Kingdom (18th Dynasty).

Dynastic stability ended with the beginning of the 13th Dynasty. According to Manetho, 60 kings reigned for 153 years, with an average of one king every three years, a definite sign of political instability. There were few or no established criteria for dynastic succession. This seems to have been a period with usurpers on one side, and king-makers and a strong administration on the other. Some of the kings were most probably of Asiatic origin, such as Chendjer, “the Boar.” It can be assumed that most of the kings previously held high positions in the court or army.

From the beginning of the 13th Dynasty, mining expeditions to the Sinai and inscriptions in the region of the Second Cataract ended abruptly. The royal mortuary cults of the 12th Dynasty also ended soon afterwards. Many Levantine peoples were employed in the Egyptian army or as servants in upper-class households. Some of these foreigners made careers in their positions, especially in the royal household, and consequently rose to positions of power, which explains the foreign names of some kings of this dynasty. With a lack of dynastic stability, political fragmentation had occurred in Egypt by 1700 B.C. and local kingdoms arose in the northeastern Delta. Of special importance was the kingdom ruled by King ‘Aasehre Nehesy, with its capital at Avaris. With the 13th Dynasty no longer in control of the whole country, its rulers withdrew to Upper Egypt. 19

During Dynasties 15 and 16 the Hyksos took advantage of Egypt’s internal weakness and seized control of Egypt. The name Hyksos is in fact derived from two Egyptian words meaning “rulers of foreign lands.” This term was used in the Middle Kingdom to refer to the leaders of the Bedouin tribes who infiltrated Egypt. Their arrival was probably achieved by infiltration rather than by significant military conquest. They probably represented a change of rulers rather than a massive influx of a new ethnic group.

Literary tradition provides some information about the Hyksos. Flavius Josephus (in Against Apion) claims to quote Manetho in stating that the invaders of an obscure race came without warning to conquer Egypt in the reign of King Tutimaios. They took the land without striking a blow and then ravaged the countryside, burning the cities, destroying temples, and massacring the people or taking women and children into slavery. They then appointed Salitis, one of their own, as king. He ruled from Memphis, levied taxes on the whole country, and positioned garrisons to protect his gains. He rebuilt and massively fortified the city of Avaris on the east bank of the Bubastite branch of the Nile.

The Hyksos also encouraged native arts and crafts and patronized literary composition. Royal programs of temple building were initiated, and they elevated Seth as their patron god. He was probably more closely associated with one of their own Asiatic deities than the “Evil One” in the Osiris myth, and his cult center was at Avaris. The Hyksos also promoted the worship of Re, Egypt’s traditional royal god.

Towards the end of this period, some hostility appears to have developed between the Hyksos and the native population. Foreigners were used increasingly to administer Egypt, and this may have led to resentment. The conflict came to a head in a confrontation between the Hyksos and the native Theban rulers (Dynasty 17). Later generations regarded these princes as heroes who expelled the Hyksos, pursuing them into southern Palestine where they finally subdued them. The Theban princes then established Dynasty 18 and the New Kingdom was founded. 20

New Kingdom (1550 B.C. to 1069 B.C.)

Lasting from approximately 1550 B.C. to 1069 B.C., the New Kingdom was a period of ancient Egyptian history characterized by prosperity and political stability following the chaos of the Second Intermediate Period. Its founder, King Ahmose I expelled the invading Hyksos, who had established a kingdom in the eastern Delta, thereby unifying Egypt once more.

Under successive kings, Egypt also began expanding its territory into foreign lands. The military grew stronger, and with it, the central government. Moreover, art and architecture flourished. A series of rulers launched major building projects, providing Egypt with some of its most significant ancient architecture. In addition, temples became larger, with workshops, storehouses, and fields. The New Kingdom was characterized by changes in worship practices as well. In particular, kings lessened their connection to the god Horus while elevating the god Re, worshiping the solar deity first as Horus-Re and then, after Egypt’s capital was moved to Thebes (a cult center for the god Amun), as Amun-Re. However, the stability of the New Kingdom was also briefly threatened by a break in traditional religion during a period now known as the Amarna Period. At this time, King Amenhotep IV (also known as Akhenaten) decided to make Aten the national god of Egypt and force his subjects to worship this deity exclusively.

This period of forced monotheism ended as soon as the king died, and the country returned to its former gods and worship practices. Other problems existed in the New Kingdom as well. Several rulers, most notably Queen Hatshepsut and several kings of the Ramessid Period, usurped the throne, and periodically a weak king would cause Egypt to lose prestige and power both abroad and at home. In fact, the New Kingdom ended when such a king, Ramses XI, essentially abdicated his power to two high priests who split the country between them. 21

Third Intermediate Period (1069 B.C. – 664 B.C.)

Smendes proclaimed himself King after the death of Ramesses XI. He effectively declared himself the heir of the Ramessid line (hence initiating the 21st dynasty) through the set of titles that he adopted. His Horus name was ‘Powerful bull beloved by Ra, whose arm is strengthened by Amun so that he may exalt Maat’. His origins are unknown and the familial links which he claims to have with Herihor seem unlikely – it is more probable that he legitimized his power by marrying a daughter of Ramesses XI. 22

The rulers of Dynasty 21 are recorded as the legitimate kings, but in fact they only exercised their power in the north. A line of high priests of Amun, established by a priest named Herihor in Dynasty 20, dominated the south from Thebes. The arrangement appears to have been amicable. One of the priests, Pinudjem I, had recognized Smendes as king and founder of Dynasty 21, and in return Smendes acknowledged him as the effective ruler in the south. These two lines had mutually recognized rights of succession in the north and south, and the families were joined by marriages arranged between Tanite princesses and Theban high priests. Through their mothers the Theban high priests thus became the legitimate descendants of the Tanite kings. Despite these arrangements, however, the country suffered from the lack of a strong, unified government.

Libyan Rulers (Dynasties 22 and 23)

On the death of Psusennes II, last ruler of the Tanite dynasty, there was no male heir, so his son-in-law, Shoshenk, a powerful chief and army commander, founded Dynasty 22 (sometimes called the Bubastite Dynasty because Shoshenk was from the Delta city of Bubastis). His family, who originally called themselves Chiefs of the Meshwesh, was of foreign origin. They were descended from the Libyans who had attacked Merenptah and Ramesses III and subsequently made their homes in the Delta, where they became successful and prosperous. During this dynasty the capital was situated either at Tanis or Bubastis, and Thebes continued as the great religious center in the south. Despite Shoshenk I’s action in appointing his second son as high priest of Amun and thus gaining control of Thebes, the country still suffered internal conflict. However, the rulers were still powerful enough to build their monuments at Bubastis and Tanis and to be buried with magnificent treasure. Shoshenk I (Identified in the Bible as King Shishak in 1 Kings 11: 40, 1 Kings 14: 25-26, 2 Chronicles 12: 2-4) was also sufficiently confident to take action abroad again, trading with Nubia and intervening in internal politics in Palestine.

The succeeding dynasties were poorly documented. According to Manetho, Dynasty 23 consisted of four kings who ruled from Tanis. This line may have ruled at the same time as some of the kings of Dynasty 22, reflecting a breakdown of centralized government. Manetho’s Dynasty 24 is certainly limited to one area, and its one recorded king ruled from Sais in the Delta. This line was descended from a prince of Sais, Tefnakhte, who had attempted to extend his power southward. His plans were curtailed by Piankhy, the ruler of a kingdom that was situated far south of Egypt. Its capital, Napata, lay near the Fourth Cataract on the Nile, where the people worshipped Amen-Re and continued many traditions of Egypt’s Dynasty 18. Piankhy campaigned in Egypt, subdued the south, and gained submission from the north before returning to Napata. 23

Nubian Rulers

The 25th dynasty was established by Shabako, whom Manetho recognizes as Sabacon. He reigned for about fifteen years and 24 his dynasty is also known as the Ethiopian or Kushite Dynasty.

The custom of pyramid building was revived by these rulers although it had ceased in Egypt hundreds of years before. Shabako’s successors, Shebitku and Taharka, inherited the kingship and Taharka was crowned at Memphis. He was an effective ruler, but he soon came into conflict with the new power in the area, the Assyrians. When the king of Judah, Hezekiah, asked Egypt for help against the Assyrians, the Egyptian forces were defeated at el-Tekeh. Assyrian expansion to gain control of the small states in Syria/Palestine met with opposition from Egypt, to whom these states appealed for help. Resentful at Egypt’s intervention the Assyrians attempted to invade Egypt (674 B.C.), but they were defeated. However, in 671 B.C. the Assyrian ruler Esarhaddon drove Taharka out of Memphis. He destroyed Memphis and removed booty and people from Egypt while Taharka fled to the south.

Esarhaddon now appointed rulers for Egypt who were selected from local governors and officials loyal to the Assyrians. One of these, Necho of Sais, would become the founder of Dynasty 26. Esarhaddon’s death allowed Taharka to reinstall himself at Memphis, but the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal attacked Egypt and regained Memphis in 662 B.C., driving Taharka first to Thebes and then to Napata. Further intrigues followed, and eventually Taharka’s nephew and successor, Tanuatamun, re-established the dynasty’s power at Memphis. However, Ashurbanipal returned again, and Tanuatamun fled to Thebes and then to Napata, while the Assyrians ransacked Amun’s temple at Thebes and transported booty back to Nineveh.

The Nubian kingdom soon ceased to exert any claim over Egypt, continuing to exist within its own boundaries. Its northern boundary was probably fixed south of the Third Cataract. The Nubians established a new capital at Meroe and continued to trade with Egypt. Aeizanes, ruler of Axum, finally destroyed Meroe in A.D. 350, but throughout this period a form of Egyptian culture continued to exist there. Egyptian-style temples flourished, and royalty were buried in pyramids; their language was written in hieroglyphs, and they produced two distinctive scripts known today as Meroitic. 25

Late Period

The Late Period of Egypt (525-332 B.C.) was the era following the Third Intermediate Period (1069-525) and preceding the brief Hellenistic Period (332-323 B.C.) when Egypt was ruled by the Argead officials installed by Alexander the Great prior to the rise of the Greek Ptolemaic Dynasty (323-30 B.C.). 26

The Late Period of Egypt began with this Nubian Dynasty, a royal family that marched northward along the Nile to restore faith and the purity of the god Amun to the people of the Two Kingdoms. Coming out of the capital at Napata, the Nubians controlled much of the Theban domain and then, led by Piankhi, moved to capture the ancient capital of Memphis. Tefnakhte, who ruled in Sais, formed a coalition of petty rulers, and they met Piankhi’s army and suffered a severe defeat. Piankhi celebrated his victory with a stela and retired to Nubia.

While the Nubians fled from the Assyrians and then regrouped to oust the Assyrians, Necho I and Psammetichus I adapted and secured their holdings. Necho I was slain by the Nubians, but his son, Psammetichus I, united Egypt and amassed a mercenary and native army. He ousted the Assyrians and began his royal line. All that Piankhi had hoped for Egypt’s rebirth was realized by this dynasty. Old traditions of faith and the skills and vision of the past flourished on the Nile. Necho II, the son of Psammetichus, followed in his stead, and the land flourished. Necho II even connected the Nile and the Red Sea with a canal.

Apries 27] came to the throne and introduced a program of intervention in Palestine, increasing trade and the use of Greek mercenaries. His involvement in Libya, however, led to a mutiny in the Egyptian army and the rise of Amasis, his general. Apries died in an attempt to regain his throne. Amasis was Hellenic in his outlook and was recorded as aiding Delphi in returning the oracle and the temple of Apollo. The city of Naukratis, ceded to the Greeks in the Delta, was started in this historical period. Psammetichus III, the last ruler of this dynasty, faced Cambyses and the invading Persian army. Psammetichus was taken prisoner and sent to Susa, the Persian capital.

Then, the Twenty-seventh Dynasty or The First Persian Period (525–404 B.C.) came, and this was not a dynasty of native Egyptians but a period of foreign occupation, also recorded as the First Persian Period. Egypt survived under foreign rule, prospering under some of the satraps and Persian kings, as the Achaemenians had problems in their own land. A court eunuch murdered some of the rulers, along with their sons, and the survivors had to endure political complications.

The Egyptians categorized Cambyses as a criminal lunatic, but he treated the nation with certain discretion in most instances. A large unit of the Persian army, sent by Cambyses to loot the Oasis of Siwa in the Western Desert, disappeared to a man. Darius I, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I, and Darius II followed Cambyses, but they faced rebellions and political intrigues at home as well as rebellions on the Nile. Darius II reigned over the Nile Valley from Persia and was viewed as tolerable as far as the Egyptians were concerned. The details of the later dynasties are given below:

Twenty-eighth Dynasty (404–393 B.C.)

Amyrtarios was a rebel in the Delta, holding the rank of prince in Sais. Egyptians felt loyal to him, and he exerted influence even as far south as Aswan. His dynasty was doomed, however, because he was judged as a violator of the laws of Egypt and was not allowed to name his son as heir to the throne. Nephrites I, the founder of the Twenty-ninth Dynasty, captured and killed him.

Twenty-ninth Dynasty (393–380 B.C.)

Nephrites I founded this line of rulers at Mendes and began to rebuild in many areas of Egypt. He maintained the Apis cult and regulated trade and government in the land. Nephrites I was followed by Psammuthis, whose brief reign was cut short by the usurper Hakoris, expanded the dynasty’s building programs. Nephrites II, Hakoris’s son and heir, did not succeed him, as Nectanbo I took the throne.

Thirtieth Dynasty (380–343 B.C.)

This royal line was founded from Sebennytos, and Nectanebo I faced a Persian army, using Greek mercenaries. The Persians bypassed a strategic fortress at Pelusium, and Nectanebo I launched a counterattack and defeated the invaders. He had a stable, prosperous reign in which he restored temples and sites and built at Philae. His son and heir, Teos, began wars to regain lost imperial lands but took temple treasures to pay for his military campaigns. He was ousted from the throne by his own royal family after only two years and fled to Susa. Nectanebo II, chosen to replace Teos, faced the Persian Artaxerxes III, who came with a vast army and reoccupied the Nile Valley.

Thirty-first Dynasty—The Second Persian Period (343–332 B.C.)

Artaxerxes III lasted only about five years and was poisoned in his own court by the eunuch Bagoas. Arses, his heir, reigned only two years before meeting the same fate. Darius III, wise to the machinations of Bagoas, made him drink the cup that he was offering to the king, and Bagoas died as a result. Darius III faced Alexander the Great, however, he was defeated in three separate battles and then slain by one of his own associates. Alexander the Great then ruled Egypt. 28

Ptolemaic Period

The Ptolemaic period was the entire epoch of Hellenistic Egypt, beginning with Alexander the Great’s arrival in Egypt in 332 B.C. and ending with the Roman conquest in 30 B.C. Within these three centuries, there was a differentiation between the period under the kings of the Macedonian dynasty (332-304 B.C.) and that of the Ptolemaic pharaohs (304-30 B.C.).

Following his victory over Darius III in the battle of Issus (late in 332 B.C.), Alexander the Great pushed on in to Egypt. The Persian satrap Mazakes ceded the country to him without a struggle. Alexander’s actions primarily belong to the sphere of religious politics and ideological history. He founded the port city of Alexandria, begun in 331 B.C., before departing to conquer the Persian Empire, and never returned to Egypt. The settlement of Babylon (323 B.C.) established Arrhidaeus Phillip III (Alexander’s incompetent half-brother) and his son, Alexander IV as coregents of the Alexandrian empire but they appear in Egyptian documents as successive pharaohs. In the wake of Alexander the Great’s death, his empire was split into parts, ruled by generals, the so-called Diadochi. Ptolemy I born in 367/6 B.C., the son of Lagus and a successful comrade in arms of Alexander seized de facto power over Egypt as satrap. 29

Ptolemy I was determined to establish himself as a regenerator of Egypt and to ensure the succession within his own family. He appointed his son as coregent and reintroduced the custom of royal brother-sister marriages. He reorganized the country and adopted the title and role of pharaoh. This allowed him to claim the religious right to rule Egypt and the political justification to own the country’s resources and impose heavy taxes. His role as pharaoh was further emphasized when he built temples to the Egyptian gods. Five examples survive at Edfu, Denderah, Esna, Philae, and Kom Ombo, where the Ptolemies were shown in the wall scenes as Egyptian kings performing the divine rituals. Ptolemy I also introduced the cult of a new hybrid deity, Serapis, who was worshipped as a combination of the Egyptian god Osiris and various Greek deities. At Alexandria he founded the cult of Alexander the Great, which laid the foundations for the later official state cult of the Ptolemaic dynasty.

There was also a dedicated attempt at Hellenization by Ptolemy I and his successors. Large communities of Greeks were now established at Alexandria, Naucratis, Ptolemais, and also in country districts like the Fayoum where farming was developed. The Ptolemies actively patronized the arts, particularly at Alexandria where the Great Library and Museum were established, and foreign scholars were encouraged to come to the city. At that time, Greek language and culture predominated in these new centers, although settlers in the country districts were more exposed to the continuing Egyptian traditions, and a degree of hybridization occurred in aspects of art, religion, and architecture.

Changes under the Ptolemies

The Greeks now formed the new upper classes in Egypt, replacing the old native aristocracy. In general, the Ptolemies undertook changes that went far beyond any other measures that earlier foreign rulers had imposed. They used the religion and traditions to increase their own power and wealth. Although they established a prosperous kingdom, enhanced with fine buildings, the native population enjoyed few benefits, and there were frequent uprisings. These expressions of nationalism reached a peak in the reign of Ptolemy IV Philopator (207–206 B.C.) when rebels gained control over one district and ruled as a line of native “pharaohs.” This was only curtailed nineteen years later when Ptolemy V Epiphanes succeeded in subduing them, but the underlying grievances continued and there were riots spelled out again later in the dynasty.

Family conflicts affected the later years of the dynasty when Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II fought his brother Ptolemy VI Philometor and briefly seized the throne. The struggle was continued by his sister and niece (who both became his wives) until they finally issued an Amnesty Decree in 118 B.C. 30 The last two decades of the Ptolemaic empire under Cleopatra VII and her coregents Ptolemy (XIII-XV) were characterized by dynastic discord and constant intervention from Rome. 31

Cleopatra, however, was ousted from the joint rulership in favor of her brother Ptolemy XIV. She seized her opportunity for power when Gaius Julius Caesar, Roman dictator from 49 to 44 B.C., followed his enemy the Roman consort Pompey to Egypt. Pompey had been appointed by the Roman Senate as the guardian of Cleopatra and her brother when their father died, but Pompey was killed by some Egyptian courtiers. Caesar now spent time in Egypt (47 B.C.), and Cleopatra’s plea to him to restore her throne was granted. Her royal powers were reinstated, her brother drowned in the Nile, and her son by Caesar, Ptolemy XV Caesarian, was adopted as her coregent.

Cleopatra’s involvement with Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony) ultimately led to the end of her dynasty. He was a Roman consul and triumvir whose early career at Rome had been supported by Julius Caesar. He had also married Octavia, the sister of Gaius Julius Octavianus, who was to become the first emperor of Rome and take the title of Augustus when he became sole ruler in 27 B.C. From thereon, Egypt became a Roman Province and lost all independence. 32

Language

The ancient Egyptians expressed their ideas in writing by means of a large number of picture signs which are commonly called Hieroglyphics. They began to use them for this purpose more than seven thousand years ago, and they were employed uninterruptedly until about B.C. 100, that is to say, until nearly the end of the rule of the Ptolemies over Egypt. 33

On the basis of ancient texts, scholars generally divide the history of Egyptian language into five periods: Old Egyptian (from 3000 to about 2200 B.C.), Middle Egyptian (2200-1600 B.C.), Late Egyptian (1550-700 B.C.), and Demotic (700-400 B.C.), and Coptic (2nd century B.C. until at least the 17th century). Thus, five literary dialects are differentiated. These language periods refer to the written language only, which often differed greatly from the spoken dialects. Coptic is still in ecclesiastical use (along with Arabic) among the Arabic-speaking Monophysite Christians of Egypt. 34

Old Egyptian was the name given to the oldest known phase of the language. Although Egyptian writing is first attested before 3000 B.C., these early inscriptions consist only of names and labels. Old Egyptian proper is dated from approximately 2600 B.C., when the first connected texts appeared, until about 2100 B.C.

Middle Egyptian, sometimes called Classical Egyptian, was closely related to Old Egyptian. It first appeared in writing around 2100 B.C. and survived as a spoken language for about 500 years, but it remained the standard hieroglyphic language for the rest of ancient Egyptian history.

Late Egyptian began to replace Middle Egyptian as the spoken language after 1600 B.C., and it remained in use until about 600 B.C. Though descended from Old and Middle Egyptian, Late Egyptian differed substantially from the earlier phases, particularly in grammar. Traces of Late Egyptian can be found in texts earlier than 1600 B.C., but it did not appear as a full written language until after 1300 B.C.

Demotic developed out of Late Egyptian. It first appeared around 650 B.C. and survived until the fifth century A.D. Coptic was the name given to the final phase of Egyptian, which is closely related to Demotic. It appeared at the end of the first century A.D. and was spoken for nearly a thousand years thereafter. The last known texts were written by native speakers of Coptic date to the eleventh century A.D.

Dialects

Besides, these chronological changes, Egyptians also had several dialects. These regional differences in speech and writing were best attested in Coptic, which had five major dialects. They cannot be detected in the writing of earlier phases of Egyptian, but they undoubtedly existed then as well: A letter from about 1200 B.C. complained that a correspondent's language was as incomprehensible as that of a northern Egyptian speaking with an Egyptian from the south. The southern dialect, known as Saidic, was the classical form of Coptic; the northern one, called Bohairic, is the dialect used in Coptic Church services today.

Hieroglyph

The basic writing system of ancient Egyptian consisted of about five hundred common signs, known as hieroglyphs. The term "hieroglyph" comes from two Greek words meaning ‘sacred carvings’ which are a translation, in turn, of the Egyptians' own name for their writing system, "divine speech." Each sign in this system was a hieroglyph, and the system as a whole was called hieroglyphic (not "hieroglyphics").

Unlike Mesopotamian cuneiform or Chinese, whose beginning can be traced over several hundred years, hieroglyphic writing seems to appear in Egypt suddenly, shortly before 3000 B.C., as a complete system. Scholars are divided in their opinions about its origins. Some suggest that the earlier, developmental stages of hieroglyphic were written on perishable materials, such as wood, and simply have not survived. Others argue that the system could have been invented all at once by an unknown genius - possibly influenced by the idea of Mesopotamian cuneiform, which is somewhat earlier.

Although people since the ancient Greeks have tried to understand this system as a mystical encoding of secret wisdom, hieroglyphic is no more mysterious than any other system that has been used to record language. Basically, hieroglyphic is nothing more than the way the ancient Egyptians wrote their language

Hieroglyphic Spelling

Each hieroglyph was a picture of a real thing that existed in the world of the ancient Egyptians. To summarize it, the individual pictures of the Egyptian hieroglyphic writing system were used in three different ways:

2. As phonograms, to represent the sounds that "spell out" individual words.

3. As determinatives, to show that the signs preceding is meant as phonograms, and to indicate the general idea of the word

Ideographic writing was simple and direct, but it was pretty much limited to things that could be pictured. All languages, however, also contain many words for concepts that cannot be conveyed by a simple picture. The idea that symbols could be used to represent the sounds of a language rather than real objects is one of the most important, and ancient, of all discoveries. 35

The empire of ancient Egypt was ruled by various races and kingdoms, but strangely, all made the same fatal mistakes which made their dynasty crumble down into pieces. Most of their governments were tyrannical and cruel, and enforced religions which were created for the sole purpose of ensuring their survival as a king rather than connecting humanity with God. Secondly, when prophets came there to lead these people to the right path, the king and his followers not only ignored them, but also conspired to martyr them. The sole reason due to which the king wanted the prophet to be martyred was that he thought that submitting to the will of God meant giving up all his power, authority and wealth. Hence, he refused blatantly and tried his best to express his animosity towards the divinely guided people. Moreover, immorality and injustice were prevalent during their rule and the condition of the poor was extremely bad. Still the elite were not bothered about the peasant class. They only cared about being the Monarch themselves or at least his favored people. Due to these and many other reasons, even the wisest people of ancient Egypt were not able to sustain their respective dynasties.

- 1 Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 115.

- 2 Lionel Casson (1969), Ancient Egypt, Time Life International, Amsterdam, Netherland, Pg. 11.

- 3 Rosalie David (2003), The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt, Routledge Taylor & Francis, New York, USA, Pg. 13.

- 4 A nome was a regional division like provinces, in ancient Egypt. Every nome was controlled by nomarch. Number of nomes changed in different times of ancient Egypt as per need and time. (Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 280.).

- 5 Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 116-117.

- 6 The Epipaleolithic or "peripheral old stone age" is a term used for the hunter-gatherer cultures that existed after the end of the last ice age, before the Neolithic.

- 7 Allan B. Lloyd (2010), A Companion to Ancient Egypt, Blackwell Publishing, Sussex, U.K., Vol. 1, Pg. 8-10.

- 8 Kathleen Kuiper (2011), The Britannica Guide to Ancient Civilizations: Ancient Egypt, Britannica Educational Publishing, New York, USA, Pg. 31.

- 9 Douglas J. Brewer (2005), Ancient Egypt: Foundations of a Civilization, Pearson Education Limited, Edinburgh, U.K, Pg. 72.

- 10 Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 117.

- 11 James Henry Breasted (1944), Ancient Times: A History of the Early World, Ginn and Company, New York, USA, Pg. 54.

- 12 Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 117-118.

- 13 James Henry Breasted (1944), Ancient Times: A History of the Early World, Ginn and Company, New York, USA, Pg. 54.

- 14 Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 117-119.

- 15 Ian Shaw (2000), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, New York, USA, Pg. 57.

- 16 Kathryn A. Bard (1999), Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Egypt, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, New York, USA, Pg. 33.

- 17 Patricia D. Netzley (2003), The Green Haven Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Green Haven Press, Michigan, USA, Pg. 117.

- 18 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 84-85.

- 19 Kathryn A. Bard (1999), Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Egypt, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, New York, USA, Pg. 57.

- 20 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 87-89.

- 21 Patricia D. Netzley (2003), The Green Haven Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Green Haven Press, Michigan, USA, Pg. 212-213.

- 22 Nicolas Grimmel (1992), A History of Ancient Egypt (Translated by Ian Shaw), Black Well Publishing Ltd., Oxford, U.K, Pg. 311.

- 23 Rosalie David (2003), The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt, Routledge Taylor & Francis, New York, USA, Pg. 93-94.

- 24 K. A. Kitchen (1973), The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100-650 B.C), Alden Press, Oxford, U.K., Pg. 148, 154.

- 25 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 94-95.

- 26 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): http://www.ancient.eu/Late_Period_of_Ancient_Egypt/: Retrieved: 31-05-2017

- 27 Apries, Hebrew Hophra, (died 567 B.C.), was the fourth king (reigned 589–570 BCE) of the 26th dynasty (664–525 BCE. Apries failed to help his ally King Zedekiah of Judah against the invading armies of Nebuchadrezzar II of Babylon, but after the fall of Jerusalem he received many Jewish refugees into Egypt. [Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/biography/Apries: Retrieved: 22-04-2019

- 28 Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 112-113.

- 29 Donald B. Redford (2001), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, New York, USA, Vol. 3, Pg. 76.

- 30 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 99-100.

- 31 Donald B. Redford (2001), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, New York, USA, Vol. 3, Pg. 80.

- 32 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 100.

- 33 E. A. Wallis Budge (1899), Easy Lessons in Egyptian Hieroglyphics with Sign List, Trench, Turner & Co. Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 01.

- 34 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/topic/Egyptian-language : Retrieved: 29-05-17

- 35 James P. Allen (2000), Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and the Culture of Hieroglyphs, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., Pg. 1-3.