Military System of Ancient Rome – Generals, Military & Navy

Published on: 01-Jul-2024(Cite: Khan, Dr. (Mufti) Imran & Hamdani, Mufti Shah Rafi Uddin. (2020), Military System of Ancient Rome, Encyclopedia of Muhammad  , Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 426-445.)

, Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 426-445.)

The Roman Empire was totally dependent on its army for its survival. Its main duty was to protect the empire and to help expand and then consolidate its geographical borders. Through this army, Rome managed to capture many tribes, confederations and empires. The army was not only the source for expanding the geographical limits of the empire but was also a source of the empire’s economic and political strength. Even though this army was one of the superior armies at the time, it still lacked the moral teachings and ethics which were necessary for a soldier because a real soldier is one who conquers the land by winning the hearts of the people and not by instilling fear and murdering thousands.

The Roman army was originally called Legio and this name, which is coeval with the foundation of Rome, continued down to the latest times. A legion comprised of an infantry, a cavalry and an artillery. The number of soldiers in a legion were not fixed but varied with moderate limits. 1 But it was precisely the army and its manpower that turned aliens into Romans. In theory only Roman citizens served in the legions. Originally, the Roman army barred those disqualified by sex or age from becoming Roman citizens. It met as an assembly in the Field of Mars outside the city boundary to elect magistrates with the power to command (imperium) potential generals. When it was in session a flag flew on a hill over the Tiber. If the flag was lowered it meant that the enemy were in sight; the assembly would end so that the participants would be ready for battle. This ritual went on until at least the 3rd century A.D. For the endless supplies of manpower, the Romans relied mainly on the resources of Italy which had become available to the legions when the Italian allies were enfranchised as a result of the Social War of 91 B.C.

Prominent Military Generals

Germanicus Julius Caeser (15 B.C. – A.D. 19)Germanicus, also called Germanicus Julius Caesar, originally named as Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, was the nephew and adopted son of the Roman emperor Tiberius (reigned 14–37 C.E.). He was a successful and immensely popular general who, had it not been for his premature death, would have become emperor.

Quaestor at the age of 21, Germanicus served under Tiberius in Illyricum (7–9 C.E.) and then on the Rhine (11 C.E.). As consul in the year 12, he was appointed to command Gaul and the two Rhine armies. His personal popularity enabled him to quell the mutiny that broke out in his legions after Augustus’s death. Although pressed to claim the empire for himself, Germanicus remained firmly loyal to Tiberius.

Early in 19 A.D., Germanicus visited Egypt, incurring strong censure from Tiberius, because the latter’s predecessor, Augustus, had strictly forbidden Romans of senatorial rank to enter Egypt (Rome’s breadbasket) without permission. 2 When he returned from Egypt, he fell ill but recovered, only to collapse again. On October 10, 19 A.D., he died. Antioch went wild with grief, joined soon by the entire Empire. It was generally held that Germanicus had been poisoned (a fact assumed by Tacitus and Suetonius), and Piso instantly received the blame. When Agrippina returned to Italy, she openly charged Tiberius and Livia with the crime, and the emperor sacrificed Piso rather than face even greater public outrage. 3

Mark Antony (83-30 B.C.)

Mark Antony or Marcus Antonius was the Roman General under Julius Caeser and later Triumvir (43-30 B.C.), who with Cleopatra (Queen of Egypt) was defeated by Octavian in last of the Civil Wars that destroyed the Roman Republic. 4 He was born into a prominent Roman family and got a reputation as a wild youth. About 58 B.C., he began his military career, serving with distinction in Egypt and Palestine and then joining Julius Caesar in Gaul. On his return to Rome, Antony held the offices of quaestor and tribune. As tribune, he opposed the Senate decree that attempted to take away Caesar's armies and weaken his power. In the civil war that followed, Antony fought along with Caesar, commanding troops at the battle in Greece and defeating Pompey, Caesar's former friend turned rival. Antony and Caesar then served together as consuls of Rome.

The assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C. abruptly changed the political situation in Rome. Antony seized Caesar's property and claimed to be his successor. Octavian made peace with Antony. They joined with Aemilius Lepidus to form the Second Triumvirate, a government in which the three leaders shared power. Antony ruled the eastern provinces and Gaul, Octavian took control of Italy and Spain, and Lepidus governed Africa. Antony had his enemies in Rome, including Cicero, killed, and in 42 B.C. he defeated Brutus and Cassius at the Battle of Philippi in Macedonia. Both Brutus and Cassius committed suicide.

While in his eastern provinces, Antony met Cleopatra, the Queen of Egypt. He became involved in a passionate relationship with this foreign ruler, which resulted in him losing support in Rome. The Romans grew increasingly critical of Antony and his foreign lover. Octavian used Antony's loss of popularity to increase his own power. He claimed that Antony planned to subject Rome to foreign rule and published Antony's will to prove this charge. In his will, Antony left large territories to his illegitimate children by Cleopatra and named Caesarion, Cleopatra's son by Julius Caesar, as Caesar's heir. Octavian then declared war on Cleopatra. The war reached a climax in September 31 B.C., when Octavian's navy defeated the forces of Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium off the coast of Greece. The couple fled to the city of Alexandria in Egypt. A year later, Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide. 5

Sulla (138-78 B.C.)

Lucius Cornelius Sulla was a ruthless military commander, who first distinguished himself in the Numidian War under the command of Gaius Marius. His relationship with Marius turned sour during the conflicts that would follow and lead to a rivalry which would only end with Marius' death. Sulla eventually seized control of the Republic, named himself dictator, and after eliminating his enemies, initiated crucial reforms. Believing he had left Rome for the better, he retreated to his villa in 79 BCE, but his reign could not forestall the fall of the Republic. 6

Pompey (106-48 B.C.)

Pompey, full name Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, was one of the greatest of all Roman statesmen and generals who played a pivotal role in the turbulent last years of the Republic. His career began in the late 80s B.C. when he commanded and won some battles for Sulla. Subsequently, Sulla, by now the dictator of Rome, granted him the honorary cognomen Magnus, meaning ‘great’ or ‘distinguished.’ In 77 B.C., Pompey went to Spain to deal with the province's rebel governor, Quintus Sertorius. Returning to Italy in 71 B.C., Pompey was just in time to aid Marcus Crassus in putting down the slave revolt led by the infamous Spartacus, after which he and Crassus were elected the consuls for 70 B.C. Soon afterward came what were perhaps Pompey's greatest triumphs. First, in 67 B.C., he was given sweeping authority by the government to rid the sea lanes of pirates, who had been menacing in the shipping and coastal towns. He did so in just forty days, sinking some thirteen hundred pirate vessels and capturing four hundred more, all without the loss of a single Roman ship. This extraordinary feat made Pompey a national hero; yet he matched it in 66 B.C. by crushing the forces of Mithridates, king of Pontus (in Asia Minor), and creating the new provinces of Bithynia, Pontus, and Syria. On his return to Rome in 61 B.C., Pompey enjoyed the most spectacular triumph staged in Rome up till that time.

Pompey seemed at the top of his form and the following year joined Crassus and Julius Caesar in forming what later came to be called the First Triumvirate. But soon his fortune began a downward spiral. In 54 B.C., his wife, Julia (Caesar's daughter, whom Pompey had married a few years earlier), died. Then the Triumvirate steadily fell apart and relations between Pompey and Caesar deteriorated, until civil war erupted between the two men in 49 B.C. The following year, at Pharsalus (in Greece), Caesar defeated Pompey, who fled to Egypt. There, the local ruler, hoping to gain Caesar's favor, had Pompey murdered. 7

Army

The Roman emperors gradually created a pool of potential legionaries, especially in Spain and Gaul and later in the Balkans. 8 The details are given below:

Early Republic

According to Roman tradition, the army as organized by Romulus consisted of 3,000 footmen, 1,000 from each of the three tribes, commanded by three tribuni militum, and 300 horsemen (celeres) under three tribuni celerum. The army was composed of various classes and the equipment of the various classes was as follows: The first had full hoplite armor after the Greek model, spear and sword, helmet, greaves, and round buckler. The second class wore no cuirass, and used the semi-cylindrical shield in place of the buckler. The third were without greaves. The fourth and fifth classes were light troops. 9

Middle Republic

Two consuls were elected at the beginning of each year, and they normally had command of the army. Each controlled two legions—a total force of 16,000 to 20,000 infantry and 1,500 to 2,500 cavalry. Praetors could also command legions, and in times of crisis a dictator was appointed, usually for six months, who took command of the whole army instead of the consuls. 10 A second in command to the tyrant was in some cases appointed by the despot himself who used to serve as ‘master of the horse’. During emergency, wide-ranging powers could be called upon from Rome's partners.

Early Empire

As the Roman realm rapidly expanded across the Mediterranean world, the army continued to increase in size, and to become better organized. Campaigns now often lasted many months or more and newly won territories required garrisons (groups of soldiers manning forts) to hold and protect them; so the army developed a hard core of professional soldiers who signed up for hitches lasting several years. 11 The state had no official strategy of remunerating these veterans with annuities and land when they retired; by the beginning of the first century B.C. this prompted inconvenience, as the dominant officers started utilizing their impact to attain such advantages for their men.

Paramilitary Force

The early years of the Principate saw the establishment of urban and praetorian cohorts, as well as the vigiles, a paramilitary force that conducted night patrols and extinguished fires. The prefects in charge of these three new forces were vested with criminal jurisdictions at various stages. The jurist Paulus states that the praefectus vigilum (‘prefect of the vigiles’) could hand out minor corporal punishments to those negligent in relation to fires, and that he had criminal jurisdiction over arsonists, burglars, thieves and robbers. 12

Auxilia

From the days of the Republic, Rome had utilized the armies of its client states and federated tribes, as well as the legions, for the defense of the Empire. These troops were the auxilia, or auxiliaries, of the imperial army. 13 The auxiliary forces provided the Roman imperial army with most of its cavalry, along with infantry units, including some specialists like archers, of lower status than the legions. Most auxiliaries were recruited from peregrine who were free non-citizen inhabitants of the empire, who received citizenship on their retirement. 14

Under Augustus, recruitments were a major part of the legionary system in the more reliable provinces, such as Germania, Africa, and the Danube. The possibility of a full Roman citizenship after 25 years of service was a great enticement. Basically, the auxilia served on the frontiers, patrolling, watching, holding the lines (border) and acting as support to the legions in battle.

There were three kinds of unit in the auxiliaries: alae or cavalry, infantry, and mixed formations of the two. The due (from the Latin for wing) normally served on the flanks in an engagement, as the Romans liked to secure their infantry in the middle and then have horsemen available to exploit any break in the enemy line. Auxiliary horsemen numbered 512 per quingenaria (unit), divided into 16 turmae (squadrons). Infantry was categorized into bodies of soldiers either 500 strong (cohors quingenaria) or 1,000 strong (cohors miliaria), broken down into centuries. Here the auxiliaries most closely resembled the legions, for they had centurions and an internal organization like that of the legion. Equipment was similar, as was weaponry, but in a pitched battle with an obstinate foe, no legate would ever risk victory by depending solely upon these troops. Mixed auxilia of infantry and cavalry, the cohors equitata, were for an unclear purpose. Aside from the aid that they gave their infantry counterparts, the mounted elements of any cohort were posted with the regular alae in a conflict and were less well equipped. Their numbers probably varied, for the quingenaria and miliaria: 480 infantry and 128 cavalry for the former, and 800 infantry and 256 cavalry for the latter. 15

Cavalry

The auxiliary cavalry was among the highest paid of Roman soldiers, partly because they had to pay for and equip their own horses. Romans were not very good horsemen, so the army raised regiments in areas where fighting on horseback was traditional, especially Gaul, Holland, and Thrace (Bulgaria). 16 The cavalry was the eyes of the military, watching and exploring in front of the armies and guarding their flanks in fight.

Logistics

When the army reached its destination, it made a fortified camp and the logistical skills of the Romans meant that they could be supplied independent of the local territory, especially in terms of food. Once supplies had reached a camp they were stored in purpose-built warehouse (horrea) which, constructed on stilts and well ventilated, better preserved perishable goods. Food stores were protected against their number one enemy - the black rat - by using cats, which were, for the same reason, also used on ships. One particular innovation of the Imperial period was the introduction of doctors (medici) and medical assistants (capsarii), who were attached to most military units. 17 There were even armed force medical clinics (valetudinarium) inside the braced camps.

Strategy

The tactics of the Roman army were initially very simple and involved confronting the enemy head-on along a common front. As the men picked up speed, they let go of a mass of flying steel shafts which was often enough to cause the enemy to turn and run. The Roman soldiers would continue to advance and kill in waves. Men on horseback would then swoop in for the kill. If there was a need to turn the enemy flanks, more cavalry support was ready for action. 18

The legionaries, when in battle-order, were no longer arranged in three lines, each consisting of ten maniples with an open space between each maniple, but in two lines, each consisting of live cohorts, with a space between each cohort. The younger soldiers were no longer placed in the front, but in reserve, the van being composed of veterans. As a necessary result of the above arrangements, the distinction between Hastati, Principes, and Triarii ceased to exist. The Velitcs disappeared. The skirmishers, included under the general term Levis Armatura, consisted for the most part of foreign mercenaries possessing peculiar skill in the use of some national weapon, such as the Balearic slingers, the Cretan archers (sayittarii), and the Moorish dart-men. When operations requiring great activity were undertaken, that could not be performed by mere skirmishers, detachments of legionaries were lightly equipped, and marched without baggage for these special services. The cavalry of the legion underwent a change in every respect analogous to that which took place with regard to the light-armed troops. The Roman Equites attached to the army were very few in number, and were chiefly employed as aids-de-camp and on confidential missions. The bulk of the cavalry consisted of foreigners, and hence we find the legions and the cavalry spoken of as completely distinct from each other. 19 After the end of the Social War, when the greater part of the inhabitants of Italy turned into Roman citizens, the antiquated qualification between the Legiones and the Socii vanished, and all who had filled in as Socii became incorporated with the Legiones.

Castration

Castration was also an important exploitive tool because it made men lose their identities in the patriarchal society. Romans thought that the survival of the family, and hence the society, relied not only on the fertility of the father to generate children but also for his fertility to infuse the crops, cattle, sheep and swine, this genius demanded the highest respect. Hence, in a patriarchal society like ancient Rome, a male’s entire identity and his agriculture stemmed from his virility. By castrating a male, the opponent was essentially stealing his identity and destroying his way of life. This was an important adaptive practice because the males in the ancient societies controlled the socio-economic and political practices of their society. If the males were castrated after a battle then that society’s whole patriarchal system came crashing down and internal warfare ensued. With internal warfare occurring, the castrator’s society would be able to invade and conquer the society. Even Aristotle in his Politics warned against the ‘disproportionate increase in any part of the state’ because it could cause political revolutions. The disproportionate number of males who were able to procreate in relation to the amount that were captured and made into eunuchs disrupted the balance of the state and cause a revolution. 20

Navy

From the time of the First Punic War, the Roman navy played a major part in allowing Rome to project its power throughout the Mediterranean and beyond. The development of the navy mirrored the evolution of the army, and under the early Principate, it became a fully professional force. It was never an independent service, but always a part of the army. 21

Rome became a major naval power when it began to expand its territory beyond Italy. Since the Romans preferred fighting on land to battles at sea, the Roman navy never became as important as the army. However, Rome used its fleets to transport troops, support land campaigns, and protect its ports. The navy also protected trade by fighting piracy. During the first 200 years of the Roman Empire, Roman naval power kept the Mediterranean Sea virtually free of pirates. Rome built its first large navy during the Punic Wars against Carthage in the 200s and 100s B.C. Despite disasters resulting from the inexperience of its sailors, the Roman navy performed well against Carthage, partly because Rome built more and larger ships than its rival. The Romans preferred heavy ships equipped with bridges that allowed Roman troops to board Carthaginian vessels, where they fought as they did on land. 22

Naval Ship

Roman warships were long war galleys based on designs from existing shipbuilding traditions, mainly Greek, with Latinized forms of Greek names. The three main types of warship were the trireme (three-er), quadrireme (fourer) and quinquereme (fiver). The standard warship of the republican fleets was the quinquereme, but it lost its pre-eminence after the battle of Actium in 31 B.C. Occasionally ‘sixes’ (probably outsize quinqueremes) were used as flagships, and Antony had galleys up to a ‘ten’ in size. Augustus, though, kept nothing larger than a ‘six’ for his flagship.

The fleets were apparently composed of a mixture of types of ship. The warships were narrow and long (generally 1 to 7 proportions). They were propelled by oars and so were superior to sailing ships as they did not rely on the Mediterranean winds. They were probably built in the same way as merchant ships. Space was very restricted, and ships could not exceed a certain size in case they broke down in rough weather.

Warships are not known to have exceeded 60m (200 ft.) in length and were usually far less. They did not stand high above the water and were not very seaworthy or stable, although they were broader and sturdier than earlier Greek ships.

The Romans adapted their warships to the tactics of land warfare by using a boarding rather than a ramming strategy. A moveable boarding bridge or gangplank (nicknamed the corvus, crow or raven) was designed to fix itself into the deck of the enemy ship. It was a boarding plank 11m (36 ft.) long and 1.2m (4 ft.) wide with a heavy iron spike at one end. It was lowered and raised by a pulley system. When raised, it stood against a vertical mast-like pole in the bow of the ship. When lowered, it projected far over the bow, and the spike would embed in the deck of the enemy ship, allowing the sailors to board. 23

Built for speed, most warships were lightweight, cramped, and without room for storage or even a large body of troops. Such logistical purposes were better achieved using troop carrier vessels and supply ships under sail. Aside from the bronze covered battering ram below the water-line on the ship's prow, other weapons included artillery ballista which could be mounted on ships to provide lethal salvoes on enemy land positions from an unexpected and less protected flank or also against other vessels. Fire balls (pots of burning pitch) could also be launched at the enemy vessel to destroy it by fire rather than ramming. 24

Incentives

The élite of the army were the praetorians, essentially the emperor’s personal guard, stationed in Rome and other parts of Italy, and enjoyed special pay and privileges. The acme of the soldier’s career, the ‘triumph’ that followed a major military victory and involved a splendid military parade through Rome, became the prerogative of the imperial family. The victorious commander, who had achieved his success as viceroy of the emperor, had to be satisfied, unless he was a member of the imperial family, with the lesser honor of triumphal insigni. 25

Weapons

The panoply (complete array of armor and weapons) of the typical Roman soldier long consisted of a cuirass (chest or upper body protection); a metal helmet; metal greaves (lower-leg protectors); a shield (the scutum, at first oval but later rectangular); a sword, usually worn on the right side, and sometimes also a dagger; and two throwing spears (javelins, known as pila; singular, pilum). Some troops, for example skirmishers like the velites of mid republican times, wore little or no armor and carried only javelins (or slings) and small round shields. Archers, most often hailing from Near Eastern lands, wore little armor and carried a curved composite bow. And by the end of the first century B.C., most soldiers no longer wore greaves (an exception being officers). Shields, swords, and javelins underwent some change in design and use. Over the time, the slightly concave rectangular scutum, for instance, had been phased out by the mid-third century A.D. in favor of an oval shield. The gladius, a sword of Spanish origin with a blade about twenty inches long, was long one of the Roman soldier's main offensive weapons. In the 2nd and 3rd centuries A.D., however, it was gradually replaced by a Celtic-style sword, the spatha, which had a blade at least two feet in length. 26

The Romans also used a javelin called pilum. It was short, about five feet long, with a heavy load of soft iron at the tip, which made up one-third of the shaft of the spear. It could not be thrown as far as some javelins, but it had greater impact. Also, because the soft iron tip bent on striking, it was of little value to the enemy, since it could not be reused. 27

Swords

In the 8th to 7th centuries B.C. swords varied from long slashing weapons to shorter stabbing ones. The longer ones are known as antennae swords, after their cast bronze handle with spiral horns. The blades were usually of bronze, sometimes iron, and were about 0.3 to 0.55 m (12 to 22 inches) long. Later on, in the century a new sword was introduced with straight parallel sides and a shorter point. The blade was 0.45 to 0.55 m (18 to 22 inches) long. In the late 2nd and early 3rd century the gladius was gradually replaced by the spatha, which was of 0.7 m (2 ft. 4 inches) long. By the end of the 3rd century all legionaries carried it. In the early empire much of the cavalry was Celtic and used the long spatha sword with a blade length of about 0.6 to 0.85 m (2 ft. to 2 ft. 9 in.) derived from the long Celtic sword.

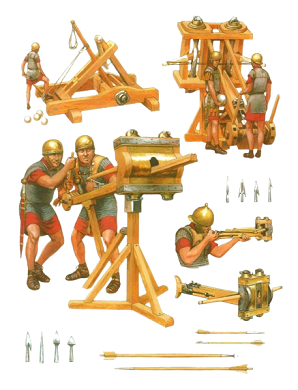

Artillery

The Romans copied and improved upon the artillery weapons used by the Greeks, but they were not used in open combat, rather, they were reserved for siege warfare in order to pound the fortifications of cities and strike terror into the defenders. The Roman machines used animal sinews instead of horse hair to increase strength and torsion, allowing them to fire projectiles over several hundred meters. Metal parts (iron and bronze) replaced wood to increase strength, stability, firepower, and durability, and springs were covered in metal cases to decrease wear from the elements. 28

From the late republic the Romans used bolt-shooting machines and stone-throwers that had twisted ropes for torsion, and worked on the principles of a crossbow. The ballistae were two-armed stone-throwing machines that could hurl stones up to 0.5 km (a third of a mile) distance and could breach walls of brick and wood, although they were less effective against stone walls. This type of machine may have continued in use to the early 3rd century but was obsolete by the 4th century. Catapultae (sing. catapulta) were two-armed machines that fired iron bolts or arrows. Some were fairly portable, and the smaller ones were called Scorpiones. They had a range of 300 m (990 ft.) or more. The standard bolt-head had a square-sectioned tapering point, a neck of varying length and a socket, and was mostly 60 to 80 mm (2 to 3 in.) long. In the 4th century, the term ballista was used for bolt or arrow-shooting machines, and the stone-throwing ballistae was used for bolt or arrow-shooting machines, and the stone-throwing ballista had gone out of use. 29

Helmets

From the earliest times in Rome, many different types of helmets are known to have been used by the tribes. In the 8th and 7th centuries B.C. Villanovan-type helmets were most common, made of two pieces of bronze joined along the edge of the crest. Another common type was the ‘bell’ helmet, most of which had cast bronze crest holders drilled through the center to take a crest pin. The Negau type of helmet was most common from the 6th to 4th centuries B.C., possibly even 3rd century B.C. It had a flat ring of bronze inside the rim with stitching holes to hold the inner cap, and normally a crest, sometimes transverse. The Montefortino-type helmet spread across the Celtic world and was adopted by the Roman army from the 4th century B.C. After this date, it continued to be worn by the Praetorian Guard with their traditional republican armor. It is estimated that some 3 to 4 million of these helmets were made. A second type of helmet is known as the Coolus helmet or jockey cap. It was a round capped bronze helmet with a small neck guard. The bronze Coolus helmet disappeared in the 1st century; from then on, all helmets were of iron. The cavalry wore helmets that covered the whole head, leaving only the eyes, nose and mouth visible, the ears being completely enclosed. Both infantry and cavalry helmets usually had a slit along the crown of the cap to hold a crest. 30

Armor

In early Rome (8th–7th B.C.) only the wealthiest soldiers wore armor, and then only a helmet and a breastplate of beaten bronze. They date to the early 7th century B.C. and continued in use to at least the end of the 6th century B.C. In the mid-2nd century B.C. the velites wore no armor other than a plain helmet sometimes covered with wolf skin. At this time the armor of the principes and hastati consisted of a small square breastplate about 200 mm (8 in.) square called a heart guard (pectorale). It was a descendant of the square breastplate of the 4th century B.C. They also wore one greave (on the left leg), although by the mid-1st century B.C. greaves were no longer worn. Around 300 B.C. mail armor (lorica hamata) was invented by the Celts, but was expensive to make and was restricted to the aristocracy. It was adopted by the legionaries and was made from rings of iron or bronze. From the mid-1st century, a new type of armor for legionaries was devised—articulated plate armor. It weighed about 9 kg. (20 lb.) Metal plates were held together by leather straps on the interior and on the exterior by straps and buckles or by hooks. With the shortening of the shield, articulated shoulder guards were developed.

Famous Battles

Punic Wars (264 -146 B.C.)As Rome grew in both strength and size, it became Carthage's major rival in the Mediterranean. Between 509 B.C. and 275 B.C., Carthage signed three treaties with Rome protecting its trading empire in exchange for promises not to interfere in Italy. Carthage even provided a fleet to help the Romans in 280 B.C. during Rome's Pyrrhic War against the Greeks. Eventually, however, the rivalry between the two states erupted in war. Carthage and Rome fought a series of three wars—known as the Punic Wars—between 264 B.C. and 146 B.C. In the first two wars, Carthage suffered embarrassing defeats and had to relinquish its territory to Rome. It was during the Second Punic War that Carthage's greatest general, Hannibal, became famous for leading his troops and elephants across the Alps in a daring invasion of Italy. The city of Carthage itself survived the first two Punic wars and remained strong. By the end of the Third Punic War, however, Carthage had lost its entire empire. Moreover, to ensure that the Carthaginians no longer posed a threat, the Romans plundered Carthage, burned it to the ground, and forbade anyone to resettle there. They took control of the remaining Carthaginian territory and formed the Roman province of Africa from its North African possessions. This marked the end of the Carthaginian Empire. 31

Latin and Samnite Wars

In 343 B.C., the Romans fought the Samnites, an association of tribes to the southeast. After a Roman victory two years later, the two sides became allies. Then they joined together to fight the tribes in the Latin League, who were beginning to challenge Rome’s authority. This Latin War ended in 338 B.C. with another Roman victory. After the war, the Latin League was broken up and Rome was clearly the dominant force in the region. Rome also expanded by founding colonies. Settlers agreed to give up their Roman citizenship in return for land. The new colonial towns were called Latin colonies, because they received the same rights as the members of the Latin League one had. Smaller settlements were known as Roman colonies, and were usually military posts. Roman citizens who moved to these colonies kept their Roman citizenship. Rome’s continuing growth led to two more wars with the Samnites. Around 327 B.C., the former allies supported opposite sides in a political struggle in the city of Naples. Their war ended more than 20 years later when neither side won. A third Samnite war began in 298 B.C. This time, the Samnites asked the Gauls and Etruscans for help in defeating Rome. But in the end, Rome and its allies won a major victory. In 290 B.C. the Samnites came under Roman control. Within the next two decades, Rome had also defeated the Gauls and the Etruscans. 32

Macedonian Wars (214-168 B.C.)

These three conflicts between Rome and Greece's Macedonian Kingdom took place in the late 3rd and early 2nd centuries B.C. and ended with the dissolution of that kingdom and the advent of Roman domination of Greece. The First Macedonian War (214-205 B.C.) was, from the Roman standpoint, a sub-conflict of the greater Second Punic War. The Macedonian king, Philip V (grandson of Antigonus Gonatas, the founder of the Macedonian Antigonid dynasty), allied himself with Rome's enemy, Carthage, and attacked various Roman outposts in Illyria (west of Macedonia). Romans formed alliances with some of Macedonia's Greek enemies, including the Aetolian League, Sparta, and Pergamum. When the Second Punic War ended (in 201 B.C.) with a resounding Roman victory. Rome wasted no time in mounting a punitive expedition against Philip. In the first year or so of the Second Macedonian War (200-197 B.C.), the Romans spent most of their time consolidating Illyria. Then, in 198 B.C. the consul Flamininus took charge of the war and pushed into Thessaly (in central Greece). There, the following year, he delivered Philip a debilitating defeat at Cynoscephalae, after which the king sued for peace. Macedonia was forced to surrender most of its warships, pay a large indemnity, and become a Roman ally. Over time, Philip's bitterness toward Rome and its interference in Greek affairs increased. When he died in 179 B.C., his son, Perseus, intrigued with various anti-Roman Greek factions. Aware of the danger Perseus posed, the Romans took the initiative and forced him into the Third Macedonian War (172-168 B.C.). In 168 B.C., the consul Aemilius Paullus crushed Perseus at Pydna and took him under guard back to Rome, where he soon died. The Romans dismantled the Macedonian Kingdom, and in 146 B.C. annexed it as a province. 33

During the 2nd century B.C., Rome was almost constantly at war. In addition to fighting in the east, the Romans battled to secure their control of the Iberian Peninsula. They also fought tribes of Gauls in the north of the Italian peninsula. In those two regions, the Romans took direct control of territory. This is because the various western tribes did not have established political and social systems that the Romans could easily influence—and be influenced by. To preserve its military gains and keep control, Rome had to leave troops behind and set up its own political systems. 34

Civil Wars (1st Century B.C.)

There were five episodes, the first was the Social War. Upset by the Roman government's refusal to grant the Italians with citizenship and civic rights, a large number of Italian towns, mostly in the central and southern sectors of the peninsula, rebelled in 90 B.C.; thousands died on both sides before the state gave in and granted citizenship to all adult men in Italy. The second round of civil strife pitted two Roman strongmen, Marius and Sulla, against each other. In 88 B.C., Sulla was elected consul and the Senate assigned him an army to quell a threat to Roman interests in Asia Minor. But the leaders of the popular party wanted their own favorite, Marius (who had been born a commoner), to lead the campaign. Sulla left for the east, fighting erupted in the streets and Marius massacred many in the aristocratic faction. Marius died soon afterward. But his supporters remained in power and faced Sulla when he returned from the east in 83 B.C. Marching on Rome a second time, Sulla regained control and then took the unprecedented action of making himself dictator. After murdering many of his opponents, he died in 78 B.C. The next civil war, which erupted in 49 B.C., involved Caesar and Pompey. After crossing the Rubicon River Caesar marched on Rome and Pompey fled, along with many senators, to Greece. In August of the following year, Caesar delivered his adversary a crushing defeat at Pharsalus, in central Greece, after which Pompey fled to Egypt, only to be murdered there by the boy-king, Ptolemy XIII. In December 47 B.C., Caesar crossed to North Africa, where he defeated the Pompeians at Thapsus (April 46 B.C.); then he traveled to Spain and destroyed the forces of Pompey's eldest son, Gnaeus, at Munda (March 45 B.C.). The fourth episode of civil strife was the short-lived resistance put up by Brutus and Cassius, the leading conspirators in Caesar's assassination in 44 B.C. Caesar's chief military associate, Antony, and heir, Octavian, marched on Greece, where Brutus and Cassius had raised a large army. In 42 B.C., at Philippi, two hard-fought battles ended with the total defeat of the republican forces and the triumph of Antony and Octavian. Octavian soon came to grips in a struggle for supremacy. The contest was decided largely by a single battle, the great sea fight at Actium (September 31 B.C.), which Octavian won. The following year, Antony and Cleopatra took their own lives, leaving Octavian sole ruler of a shattered, war weary Roman world. The Republic was dead and he proceeded, with his new name of Augustus, to erect the Empire on its ruins. 35

Gallic Wars

Conflicts between the Roman Legions under the command of Julius Caesar and the many tribes of Gaul (Gallia); raged between 58 and 51 B.C. These wars demonstrated the genius of Julius Caesar, the skills of the legions, the indomitable spirit of the Gauls and the damage that could be inflicted on cities, territories and entire populations in Rome's drive to world domination. In 59 B.C., a tribune of Caesar's own party, Vatinius, made the proposal to the Senate that Caesar be granted the governorship of Illyricum, Gallia Cisalpina and Gallia Transalpina for five years. Gathering together all available troops, Caesar surprised the advancing horde at the Arar River. A battle followed, in which some 30,000 Helvetii were annihilated. In July of that year another engagement took place at Bibracte; the Helvetians struck first, but they were repulsed, pushed back into their camp and massacred. Some 130,000 to 150,000 men, women and children were slain. Only 110,000 Helvetians were left to begin the long march home, and Caesar noted that he had earned the acclaim of Gaul's many chieftains. In year 57 B.C., the Romans pushed into Belgica, defeating an army at Axona under King Galba. Early in 56 B.C. Caesar set out against the tribes of western Gaul. A sea battle between Brutus Albinus and the ships of the Veneti helped seal Armorica's fate. In 55 B.C. Germanic tribes, the Usipetes and the Tencteri, pushed by the stronger Suebi, crossed the Rhine and tried to settle in Gaul along the Meuse River. Perhaps half a million Germans were living in the area. Caesar first tried to negotiate with them, in vain. Then Caesar allowed his soldiers to wipe out the tribes, slaughtering hundreds of thousands. Those who survived asked to be placed under his protection. Throughout late 53 B.C., the leader of the Averni, Vercingetorix, prepared his army, supplied it, trained it and used discipline and organization to make it formidable. At the start of 52 B.C. he struck, knowing that Caesar was in Italy. Caesar swept the field, taking Villaunodonum and Cenabum (Orleans) and Noviodonum. A siege of Avaricum netted Caesar a brilliant victory. From July to the fall of 52 B.C., Caesar conducted a masterful operation in siege warfare enduring massive sorties from within the city and from outside forces. Starving, Vercingetorix surrendered. In another year, the whole district was appeased and given the new name of Gallia Coma ta. For almost eight years Julius Caesar kept fighting and was responsible for the killing of one million individuals in order to promote the spread of Roman rule.

Marcomannic Wars

A series of bitter struggles were fought between the Roman Empire and a number of barbarian tribes from circa 166 to 175 and 177 to 180 A.D. By the start of the reign of Marcus Aurelius in 161 A.D., the pressure along the frontiers was becoming serious. Pushed by the new peoples moving toward the West, those tribes already established along the Rhine and Danube realized that their only hope for survival was to break into the provinces of the Roman Empire, to take for themselves the necessary territories. By the summer of 166 or 167, a small army of the Ubii and Langobardi crossed into Pannonia Superior, where they had to be routed in a series of counterattacks. In that same season a full-scale invasion swept across the Danube, as a host of the Marcomanni, under King Ballomar and aided by the Quadi, Langobardi, Vandals and other, minor tribes, marched toward Italy. A Roman army sent against them was broken, and Aquileia was besieged. The Italians faced disaster. Marcus and Verus immediately took steps to halt the invasion. The Alpine passes were blocked, defenses improved, reinforcements summoned and new legions levied. By early 168 A.D., however, the counterattack was launched. Aquileia was relieved and Illyricum scoured clean of the invaders. Around 170 A.D., a new torrent poured down on the frontiers, as the Chatti, Chauci, Sequani and Lazyges tribes made incursions into Germania, Gallia Belgica and throughout the Danubian Theater. Each new threat was met and defeated through hard combat, stubborn will and good fortune. In 175 A.D., Marcus Aurelius' legions were hemmed in by the Quadi, who used the summer's heat to induce them to surrender; without water, the soldiers were withering. The battle was won, and Marcus rewarded all the soldiers with the title of ‘Thundering Legion’.

The imperial plan, as envisioned by Marcus, was to convert the territory of the barbarians into the Trans-Danubian provinces, far stronger than Trajan's Dacia. His hopes were left unfulfilled, as he died on March 17, 180 A.D., begging Commodus to finish his campaigns. Commodus chose to return to Rome, make peace with the various nations and end the Marcomannic Wars. Not only did Rome advance into northern Europe during these campaigns and then withdraw, but also thousands of prisoners were allowed to return home. Many thousands more were settled on land in Italy and in the provinces. These immigrants soon participated in the affairs of the Empire, while supplying the army with fresh troops. Marcus Aurelius rendered the Marcomannic Wars an eventual success for the barbarians by helping to Germanize the Roman world. 37

Persian Wars

The conflicts along the eastern border of the Roman Empire, which saw Rome and Parthia struggle for supremacy in the Middle East from the middle of the 1st century B.C. onwards, received a new boost after the Sassanid dynasty came to power in Iran (in approximately 227 A.D.). Ardashir, the first member of Iran's new dynasty, began a policy of aggression toward his rivals shortly after consolidating power. In 230 A.D., Sassanid troops invaded Roman-controlled northern Mesopotamia, besieging Nisibis and entering into Syria and Cappadocia. Alexander Severus attacked the Persians (231-232 A.D.) using veteran troops from the Danube. The Romans were defeated, suffering serious losses. Although the military campaign resulted in a series of Roman victories, neither of the two sides was completely able to obtain a decisive victory. In 237-238 A.D., Ardashir captured Carrhae and Nisibis, and in 239 A.D. he attacked the Roman base of Dura-Europos on the Euphrates, while shortly afterwards he took Hatra following a long siege. In 243 A.D., Emperor Gordian III led a powerful army against the Persians and managed to expel the Persians from Syria and northern Mesopotamia, but later suffered a disastrous defeat at Misiche in the modern province of Al-Anbar, near Ctesiphon, before being assassinated by his own men. In 298 A.D., peace was concluded on terms moderated by Diocletian. Mesopotamia returned to Roman control and the border between the two empires was fixed at the rivers of Araxes, Khabur, and Tigris. The Anastasian war of 502- 506 A.D. was again the result of a crisis at the Persian court. After some initial successes, the war began to swing in Anastasius's favor and when a settlement was reached in 506 A.D., a key achievement was the fortification of Dara, which allowed the Romans once more to benefit from a fortified frontier base. 38

Role of Women in War

Women did not serve in the army because Romans considered it improper for a woman even to watch military maneuvers. 39 During the early centuries of the Republic, Rome had been ceaselessly at war, which meant that Roman men were constantly away from home for long periods at a time. This resulted in the Roman women becoming of necessity responsible for many of the duties usually performed by the men. They had to look after not only the house, but all the property and in some cases the farm; they controlled the slaves both indoors and out, and they superintended the education of the children, not only of the girls but of the younger boys as well. 40 Apart from a few extreme cases, women, children, and the elderly all belonged to the civilian category in ancient societies, since their weaknesses were widely recognized. They were generally but not always spared the worst treatment, such as torture or massacre, but nevertheless endured other abuses: for instance, raping women was an accepted part of any victory, and the sources only refer to it when it did not occur, to underline the singularity of the situation. 41

Roman soldiers were forbidden to marry but many had common law wives and children living in the village. 42 Women worked in workshops for fulfilling the needs of soldiers. Gynaecea was a workshop where women made clothes for soldiers. 43

Immorality

Sex among fellow soldiers violated the Roman decorum against intercourse with another freeborn male. A soldier maintained his masculinity by not allowing his body to be used for sexual purposes. This physical integrity stood in contrast to the limits placed on his actions as a free man within the military hierarchy; most strikingly, Roman soldiers were the only citizens regularly subjected to corporal punishment, reserved in the civilian world mainly for slaves. Sexual integrity helped distinguish the status of the soldier, who otherwise sacrificed a great deal of his civilian autonomy, from that of the slave. In warfare, rape signified defeat, another motive for the soldier not to compromise his body sexually. 44

The soldiers of the Roman army were not allowed to marry. Hence when it was on the march or at a permanent fort, it was accompanied by a number of camp followers who included prostitutes. 45 Apart from these prostitutes, other forms of sexual gratification available to soldiers were the use of male slaves, war rape, and same-sex relations. 46

During wartime, the violent use of war captives for sex was not considered criminal rape. Mass rape was one of the acts of punitive violence during the sack of a city, 47 but if the siege had ended through diplomatic negotiations rather than storming the walls, by custom the inhabitants were neither enslaved nor subjected to personal violence. Mass rape occurred in some circumstances, and is underreported in the surviving sources 48 to show that the ancient Romans were not cruel and followed ethical and moral values.

Genocide

Genocide occurred in two forms on the Roman scene. The external form encompassed acts of unbridled savagery, of virtual extermination, against large groups of non-Romans. In the internal form, Romans systematically annihilated each other. External genocide was stigmatized by Seneca as:

‘We are a mad people, checking individual murders but doing nothing about war and the ‘glorious’ crime of slaughtering whole peoples under the authority of duly enacted laws.’

Sulla was very famous for internal and external genocides. Sulla’s external victims were the Samnites, who had come perilously close to ending Rome’s drive for empire before it began. Later on, in 82 B.C., the Samnites, long seen as ‘the old enemy’, fought on Marius’ side in the civil war against Sulla. Sulla defeated them in a decisive battle at the Colline Gate of Rome. Sulla took more than 8,000 prisoners, but because they were mostly Samnites, he killed them, though only after accepting their surrender and imprisoned them for three days, after which he told his soldiers to butcher them. This breach of a deditio in fidem was pure savagery; it had neither the strategic objectives of Aemilianus nor a commercial interest in selling them into slavery. But Sulla was only at the start of his murderous career. At Praeneste, he paraded prisoners in three sections, consisting of Romans, Samnites and Praenestians. The Romans were pardoned, but the male Samnites and Praenestians were put to death. Their wives and children were spared to be raped and enslaved, but Sulla was determined to exterminate the Samnites. Hence, he declared that no Roman could live in peace as long as the Samnites survived as a separate nation.

A systematic campaign of extermination was launched in Samnium, at the end of which some towns had vanished, while others had become mere villages. Visitors to the region refused to believe that Samnium had ever existed. Sulla’s final solution was not his only barbaric act at this time. He is also said to have transported 6,000 townsmen of Antemnae to the Circus Flaminius in Rome and to have had them butchered while he was addressing the senate.

In the same year, 82 B.C., Sulla turned to domestic genocide. Installed as dictator, he was able to adopt a more legalistic approach this time. Laws of the people made him dictator ‘to write laws and reconstitute the state’, with power ‘to put any citizen to death without trial’ and to organize the proscriptions. With the implements of state terrorism in place, Sulla went ahead with the proscriptions. He posted up the names of people who were liable to be killed with impunity. Rewards were paid to assassins; this meant that killings had to be by decapitation, because payment of the reward depended on production of the severed head. The property of the proscribed was confiscated, burial and mourning were denied them, and civil disabilities were imposed on their children. The number of victims of Sulla fluctuate in the sources. The best estimate is Appian’s 105 senators, 2,600 knights and an unspecified number of others, but the true figure was even bigger, but remains hidden.

The vision of the Roman military was nothing but expansion through any means, terrorism, and survival by plundering other nations, almost the same vision which the so-called protectors of human rights have these days. On one side, they claim to be the champions of human rights, while they keep on murdering innocent people on the other. Secondly, these nations blame Islam and the Muslims for genocides and other cruel acts, while the books of history clearly show that the largest genocides and cruel acts were conducted by none other than the Romans who murdered millions and millions of people, enslaved almost a similar number so that they could expand their territory and sustain it. Some even waged wars for personal benefits, but in those wars, no rules were followed, women were raped and murdered, children were made slaves or were killed and the places were terrorized. Still though, these acts of terror are entitled as acts of valor and the vicious animals in the form of humans are celebrated. While the people who showed mercy, waged war not for desire, but to establish justice, peace and prosperity were presented as villains and an inferior species.

The people who are presented as villains are none other than Muslims, even though it was Islam which taught its followers to not attack the women and children, leave the farms unharmed, leave the elderly and those who do not wish to fight unharmed, and only fight those who come out to fight. History is filled with countless instances of ethical treatment done by the Muslims during the war, but in this age of disinformation and deception, the opinion makers prefer to close their eyes and betray humanity by providing the wrong facts and misguiding the people.

- 1 William Smith (1889), A Smaller History of Rome, Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York, USA, Pg. 122.

- 2 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/biography/Germanicus Retrieved: 14-11-2018

- 3 Mathew Bunson (1994), Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 443.

- 4 Meriam-Webster Authors (1995), Meriam-Webster’s Encyclopedia of Literature, Meriam-Webster’s Inc. Publishers, Massachusetts, USA, Pg. 59.

- 5 Carrol Moulton (1998), Ancient Greece and Rome: An Encyclopedia for Students, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, USA, Vol. 1, Pg. 36-37.

- 6 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): https://www.ancient.eu/sulla/: Retrieved: 06-12-2018

- 7 Don Nardo (2002), The Green Haven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Green Haven Press, California, USA, Pg. 52.

- 8 Barbara Levick (2000), The Government of the Roman Empire, Routledge, London, U.K., Pg. 4-5.

- 9 H. Stuart Jones (1912), Companion to Roman History, Oxford at the Clarendon Press, Oxford, U.K., Pg. 195-196.

- 10 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2004), Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 64-65.

- 11 Don Nardo (2002), The Green Haven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Green Haven Press, California, USA, Pg. 253.

- 12 Paul ErdKamp (2013), The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Rome, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., Pg. 412.

- 13 Mathew Bunson (1994), Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 564.

- 14 David S. Potter (2006), A Companion to the Roman Empire, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, U.K., Pg. 211.

- 15 Mathew Bunson (1994), Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 564-565.

- 16 Dr. Simon James (2008), Eye Witness Ancient Rome, DK Publishing, London, U.K., Pg. 13.

- 17 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): https://www.ancient.eu/Roman_Warfare/: Retrieved: 22-12-2017

- 18 Image Publishing (Author), Book of Ancient Rome, Image Publishing, London, U.K., Pg. 137.

- 19 William Smith (1889), A Smaller History of Rome, Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York, USA, Pg. 124.

- 20 Caitlin Elis (2012), The Berkeley Undergraduate History Journal: Clio’s Scroll, Phi Alpha Theta, Florida, USA, Vol. 14, Pg. 8-9.

- 21 Phillip Sabin, Han Van Wees & Michael Whitby (2007), The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., Vol. 2, Pg. 104.

- 22 Carrol Moulton (1998), Ancient Greece and Rome: An Encyclopedia for Students, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, USA, Vol. 3, Pg. 69.

- 23 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2004), Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 74-75.

- 24 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): https://www.ancient.eu/Roman_Naval_War fare/: Retrieved: 26-10-2018

- 25 Anthony A. Barrett (2001), Agrippina: Sex, Power and Politics in the Early Empire, Routledge, London, U.K., Pg. 3.

- 26 Don Nardo (2002), The Green Haven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Green Haven Press, California, USA, Pg. 250-251.

- 27 Carroll Moulton (1998), Ancient Greece and Rome, Simon & Schuster Macmillan, New York, USA, Vol. 4, Pg. 132-133.

- 28 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): https://www.ancient.eu/Roman_Siege_Warfar e/: Retrieved: 20-02-2019

- 29 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2004), Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 92.

- 30 Ibid, Pg. 85-91.

- 31 Carroll Moulton (1998), Ancient Greece and Rome, Simon & Schuster Macmillan, New York, USA, Vol. 1, Pg. 114.

- 32 Michael Burgan (2009), Great Empires of the Past: Empire of Ancient Rome, Chelsea House Publishers, New York, USA, Pg. 23-24.

- 33 Don Nardo (2002), The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Greenhaven Press Inc., San Diego, California, USA, Pg. 280.

- 34 Michael Burgan (2009), Great Empires of the Past: Empire of Ancient Rome, Chelsea House Publishers, New York, USA, Pg. 31.

- 35 Don Nardo (2002), The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Greenhaven Press Inc., San Diego, California, USA, Pg. 270-271.

- 37 Mathew Bunson (1994), Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 637-639.

- 38 Yann Le Bohec (2015), The Encyclopedia of the Roman Army, John Wiley & Sons Ltd., The Atrium, West Sussex, U.K., Vol. 2, Pg. 743-744.

- 39 Carroll Moulton (1998), Ancient Greece and Rome, Simon & Schuster Macmillan, New York, USA, Vol. 4, Pg. 139.

- 40 Dorothy Mills (1937), The Book of the Ancient Romans, G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, USA, Pg. 340.

- 41 Yann Le Bohec (2015), The Encyclopedia of the Roman Army, John Wiley & Sons Ltd., The Atrium, West Sussex, U.K., Vol. 2, Pg. 390.

- 42 Peter Conolly (2010), Soldiers of Ancient Rome in Campaigns and in a Life: the Roman Fort, Artsfumato, Vienne, France, Pg. 12.

- 43 Yann Le Bohec (2015), The Encyclopedia of the Roman Army, John Wiley & Sons Ltd., The Atrium, West Sussex, U.K., Vol. 2, Pg. 454.

- 44 Sara Elise Phang (2001), The Marriage of Roman Soldiers (13 B.C.–A.D. 235). Brill, Boston, USA, Pg. 93-94.

- 45 Pat Southern (2006), The Roman Army: A Social and Institutional History, Oxford University Press, Oxford, U.K., Pg. 144.

- 46 Sara Elise Phang (2001), The Marriage of Roman Soldiers (13 B.C.–A.D. 235). Brill, Boston, USA, Pg. 3.

- 47 Ibid, Pg. 244, 253-254, 267-268.

- 48 C. R. Whittaker (2004), Rome and Its Frontiers: The Dynamics of Empire, Routledge, Abingdon, U.K., Pg. 128-132.