Political System of Ancient Rome – Kings, Senate & Emperors

Published on: 29-Jun-2024(Cite: Khan, Dr. (Mufti) Imran & Hamdani, Mufti Shah Rafi Uddin. (2020), Political System of Ancient Rome, Encyclopedia of Muhammad  , Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 392-409.)

, Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 392-409.)

After its legendary founding, the Roman took on many forms of government over a period of time. It started off with monarchy, then involved in to an oligarchy and a republic and then finally became an empire. The Western civilization believes that it is indebted to the people of ancient Rome due to their contributions in the field of art, philosophy, and literature and especially in politics. However, if the political history and system of the ancient Roman civilization is studied thoroughly, one finds more harm than good in it. The ancient Roman political system was made only to benefit a class of the chosen few and not the society as a whole. At the foundation of that system were the phrases of 'might is right' and materialism. This is why history records that the Romans ravaged and destroyed many civilizations just for the sake of their personal lust and greed. They did not make societies prosperous but rather pillaged and robbed them and killed those who opposed them. Hence this 'gift' by the ancient Roman civilization has done no good to the world. Just like olden days, the power lies with a few who do whatever they like and are unanswerable for it.

Prominent Rulers

The political system of ancient Rome had many leaders who were famous for different traits such as development, military skill, management, lust and notoriety. Their details are given below:

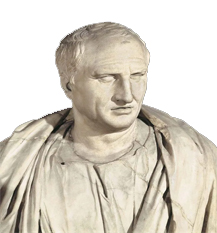

Cicero (106-43 B.C.)Marcus Tullius Cicero was a prominent man at Rome for some time in the latter years of the Republic. 1 He was born in the town of Arpinum in 106 B.C. in an equestrian family. 2 He was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, and writer who vainly tried to uphold republican principles in the final civil wars that destroyed the Roman Republic. 3 His written work mostly comprised of the speeches which were written down by others and presented to the world. 4

He rose to the office of consul and the lifetime Senatorial membership. It subsequently conferred by his audacious wit as a lawyer and orator in public prosecutions. His greatest moment as consul in 63 B.C. came in exposing a conspiracy by Catiline; the brutal suppression of the conspiracy by executing Roman citizens without trial, however, would tar his political legacy. He became an enemy of Julius Caesar (though accepting a pardon from him at the end of a stretch of civil wars in 47 B.C.), seeing the assertion of power first by Caesar and then Mark Antony as fatal to the republic. In 43 B.C., Cicero was murdered in response by partisans of the then-ruling Triumvirate to which Antony belonged. 5

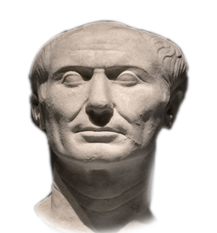

Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.)

Gaius Julius Caesar was born 12 July 100 B.C. (though some cite 102 as his birth year). His father, also Gaius Julius Caesar, was a Praetor who governed the province of Asia and his mother, Aurelia Cotta, was of noble birth. Both held to the popular ideology of Rome which favored democratization of government and more rights for the lower class as opposed to the Optimate factions’ claim of the superiority of the nobility and traditional Roman values which favored the upper classes.

He initiated many reforms including further land redistribution among the poor, land reform for veterans which eliminated the need to displace other citizens, as well as political reforms which proved unpopular with the senate. He ruled without regard to the senate, usually simply telling them which laws he wanted passed and how quickly, in an effort to consolidate and increase his own personal power. He reformed the calendar, created a police force, ordered the rebuilding of Carthage, and abolished the tax system, among many other pieces of legislation (of which quite a few were long-time Popular goals). His time as dictator was generally regarded as a prosperous one for Rome but the senators, and especially those among the Optimate faction, feared that he became too powerful and could soon abolish the senate entirely to rule absolutely as a king.

On March 15, 44 B.C., Caesar was assassinated by the senators in the portico of the basilica of Pompey the Great. Among the assassins were Marcus Junius Brutus, Caesar’s second choice as heir, and Gaius Cassius Longinus, along with many others (some ancient sources cite as many as sixty assassins). Caesar was stabbed twenty-three times and died at the base of Pompey’s statue. 6

Augustus Caesar (63 B.C.–14 A.D.)

The first Roman emperor that bore the honorary title of ‘Augustus’ was born on Sept. 23, 63 B.C. and died at Nola, Campania, Aug. 19, 14 A.D. He was the son of Gaius Julius Caesar Octavius. 7 He was only 19 years of age when Caesar was murdered in the Senate house (44 B.C.), but with a true instinct of statesmanship he steered his course through the intrigues and dangers of the closing years of the republic, and after the battle of Actium was left without a rival. Some difficulty was experienced in finding a name that would exactly define the position of the new ruler of the state. He himself declined the names of rex and dictator, and in 27 B.C. he was by the decree of the Senate styled Augustus. The epithet implied respect and veneration beyond what is bestowed on human things. 8

The month of August was named in his honor. In the year 19 B.C., he was given Imperium Maius (supreme power) over every province in the Roman Empire and, from that time on, Augustus Caesar ruled supremely, the first emperor of Rome and the measure by which all later emperors would be judged. By 2 B.C. Augustus was declared Pater Patriae, the father of his country.

The peace which Augustus restored and kept (the Pax Romana) caused the economy, the arts and agriculture to flourish. An ambitious building program was initiated in which Augustus completed the plans made by Julius Caesar and then continued on with his own grand designs. 9 His last words were:

‘I found Rome as a city of brick but left it one of marble.’ 10

Claudius (10 B.C.-54 A.D.)

Claudius was born at Lugdunum on the Kalends of Augustus in the consulship of Iullus Antonius and Fabius Africanus, the very day when an altar was first dedicated to Augustus in that town, and he received the name of Tiberius Claudius Drusus. Later, on the adoption of his elder brother into the Julian family, he took the surname Germanicus. He lost his father when he was still an infant, and throughout the course of his childhood and youth he suffered so severely from various obstinate disorders that the vigor of both his mind and his body was dulled, and even when he reached the proper age he was not thought capable of any public or private business. For a long time, even after he reached the age of independence, he was in a state of pupillage and under a guardian, of whom he himself makes complaint in a book of his saying that he was a barbarian and a former chief of muleteers, put in charge of him for the express purpose of punishing him with all possible severity for any cause whatever. It was also because of his weak health that, contrary to all precedent, he wore a cloak when he presided at the gladiatorial games which he and his brother gave in honor of their father; and on the day when he assumed the gown of manhood he was taken in a litter to the Capitol about midnight without the usual escort.

Yet he gave no slight attention to liberal studies from his earliest youth, and even published frequent specimens of his attainments in each line. But even so he could not attain any public position or inspire more favorable hope of his future. 11 He was also known as ‘Claudius the Idiot’ or ‘Claudius the Stammerer’ or ‘Clau-Clau-Claudius’ or at best as ‘Poor Uncle Claudius’. 12 Later on, he married four times but had poor luck with women. 13 Claudius was also known for initiating the incestuous practice of marriage between uncles and nieces in ancient Rome by marrying his own niece Agrippina. 14

He reigned for over 13 years (41-54 A.D.), having succeeded Caius (Caligula) who had seriously altered the conciliatory policy of his predecessors regarding the Jews and, considering himself a real and corporeal god, had deeply offended the Jews by ordering a statue of himself to be placed in the temple of Jerusalem, as Antiochus Epiphanes had done with the statue of Zeus in the days of the Maccabees. Claudius reverted to the policy of Augustus and Tiberius and marked the opening year of his reign by issuing edicts in favor of the Jews, who were permitted in all parts of the empire to observe their laws and customs in a free and peacefull manner, special consideration being given to the Jews of Alexandria, who were to enjoy without molestation all their ancient rights and privileges. The Jews of Rome, however, who had become very numerous, were not allowed to hold assemblages there, an enactment in full correspondence with the general policy of Augustus regarding Judaism in the West.

Whatever concessions were given to the Jews by Claudius may have been induced due to the friendship for Herod Agrippa. With the reign of Claudius is also associated the famine which was foretold by Agabus. Classical writers also report that the reign of Claudius was, from bad harvest or other causes, a period of general distress and scarcity over the whole world. 15

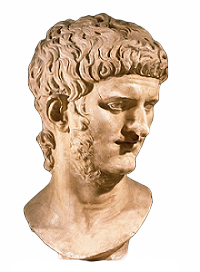

Nero (37-68 A.D.)

Nero, in full Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus 16 was the last Roman emperor (reigned 54 A.D. – 68 A.D.) of the Julian-Claudian line, was the son of Domitius Ahenobarbus and Julia Agrippina, niece of Emperor Claudius. 17 The brutal reign of Rome's fifth emperor, the self-centered, cruel, and extravagant Nero, symbolized the misuse of great power; numerous despicable acts which were attributed to him. He was born in 37 A.D. in the small seaside town of Antium (about fifty miles south of Rome) and was the son of Agrippina the Younger, great-grand daughter of Augustus and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, and an aristocrat with a reputation for shady dealings. In 49 A.D., Agrippina married the fourth emperor, Claudius, who the following year adopted the boy as his son.

With her son now the heir apparent, in 54 A.D. the scheming and ambitious Agrippina had Claudius poisoned and the seventeen-year-old Nero ascended the throne as Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus. At first, it appeared to all that Nero might become a responsible, constructive leader. The accounts of Suetonius, Tacitus, Dio Cassius, and other ancient historians all agree that in his first months in power he tried hard to be generous and enlightened. But it is unclear how much of this early good behavior stemmed from Nero's own character and how much from the influence of Seneca, the philosopher writer who had been his tutor. Evidence suggests that Seneca made a concerted effort to guide and restrain the youth, who, at least privately, must have revealed signs of a neurotic, cruel, and violent nature.

Unfortunately, Nero eventually revealed his dark nature and his reign grew increasingly more brutal and despotic. Among the close relations, he murdered his stepbrother, his mother, his first wife (Octavia), and his second wife (Poppaea). He also illegally confiscated the properties of several wealthy men, all to help finance his own excessive luxuries. As his misdeeds multiplied, Nero came to ignore Seneca and other responsible advisers and from 62 A.D. onwards he relied mainly on the advice of Ofonius Tigellinus, the ambitious commander of the Praetorian Guard, who encouraged his irresponsible and violent behavior.

Nero's greatest notoriety came in the wake of the terrible fire that devastated about two-thirds of the capital city in July 64 A.D. It has been stated that he organized shelters for the homeless and launched ambitious rebuilding projects. But many Romans became convinced that he himself had purposely started the blaze. Their suspicions stemmed in part from his transformation of a large area destroyed by the fire into his own personal pleasure park and palace (the Golden House). Many Romans came to see this waste of valuable public space as just another of Nero's outrages and several highly placed individuals began to plot his assassination. To their regret, he discovered their schemes and responded by torturing, executing, or exiling hundreds of people. Among these unfortunates was Seneca, whom he ordered to commit suicide.

The decadent emperor's own days were numbered, however. Early in 68 A.D., Roman troops in various parts of the Empire began proclaiming their commander’s emperor; soon afterward the Senate declared Nero an enemy of the people. Fleeing in disguise to a villa a few miles north of the city, the disgraced ruler took his own life when he realized that the soldiers hunting him were closing in. 18

Justinian (482 –565 A.D.)

Flavius Anicius Julianus Justinianus was born about 482 A. D. at Tauresium (Taor) in Illyricum (near Uskup). In 521 A.D. Justinian was proclaimed consul, then general-in-chief, in April, 527 A.D. In August of the same year Justin died, and Justinian was left sole ruler. The 38 years of Justinian's reign were the better period of the later empire. He tried to achieve the task of reviving their glory. The many-sided activity of this emperor may be summed up under the headings of military triumphs, legal work, ecclesiastical polity, and architectural activity 19 which was baseless from any divine guidance and was full of worldly achievement without considering the matter of hereafter which is a sole purpose of this life according to the teaching of all divine religions.

Toward the end of his reign, Justinian to some extent withdrew from public affairs and was occupied with theological problems. He even lapsed into heresy when, at the end of 564 A.D., he issued an edict stating that the human body of Christ was incorruptible and only seemed to suffer (the doctrine called Aphthartodocetism). This roused immediate protest, and many ecclesiastics refused to subscribe to it, but the matter was dropped with the emperor’s death, at which time the throne passed to his nephew Justin II in A.D. 565. 20

The Five Emperors (96-180 A.D.)

A series of so called Five Good Emperors: Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius—ruled Rome between A.D. 96 and A.D. 180. Nerva reigned for only 16 months before being succeeded by his adopted son Trajan, who became one of the most popular of all the emperors. Trajan's aggressive foreign policy led to the conquest of Dacia and the defeat of the Parthians. At home, he reduced taxes, sponsored a massive public building program, and showed great respect for the Senate, which proclaimed him optimus maximus (best and greatest) in A.D. 114. While returning from the east in A.D. 117, Trajan suffered a fatal stroke. His cousin and designated heir, Hadrian assumed power. Hadrian felt that Trajan's conquests had overextended the empire, so he pulled back from territory won in the east. He developed a policy of strengthening the frontiers of the empire rather than expanding them. Prosperity continued under Hadrian, who also reduced taxes and encouraged public works projects. One of Rome's hardest-working emperors, Hadrian spent many years traveling from province to province and dealing with local problems. Near the end of his life, he suffered from serious illness and became concerned about the succession when his chosen heir died unexpectedly. Before his death, he adopted the respected senator Antoninus Pius as his heir. When Hadrian died in A.D. 138, the Senate looked forward to rule by one of its own members. Antoninus Pius had a long, peaceful, and prosperous reign. He ruled with great concern for the welfare of the people and even refused to travel because he did not want to be a burden on the places he might visit. Antoninus had adopted his nephew Marcus Aurelius as heir, according to the wishes of Hadrian. Thus, even the issue of succession was not a problem. When Marcus Aurelius became emperor in A.D. 161, ominous signs of trouble began to arise. Problems in Rome's eastern provinces and with the Germans along the Danube River rapidly became crises, and the emperor spent much of his time fighting wars. A thoughtful and energetic ruler, Marcus put down most of the uprisings he faced. But his son and successor, Commodus, was the first of many bad or mediocre emperors who presided over Rome's gradual decline. 21

Political System of Ancient Rome

The nature of political life is a topic important for the understanding of any state; unfortunately, in the case of the Roman Republic, it is also a matter of considerable controversy. 22 Although ancient and modern historians disagree over when Rome was founded, they do agree that the first rulers were kings. 23 There were three phases in the Government of ancient Rome:

- The Kingdom (753-509 B.C.)

- The Republic (509-31 B.C.)

- The Empire (27-476 A.D.) 24

Roman Kingdom (753-509 B.C.)

The Roman government and state were ruled by kings and directly preceded the foundation of the Republic. The exact length of the monarchial period (the Monarchy), as well as the number of kings and the lengths of their reigns, is not precise. 25

Of the entire area which was subject to the Romans, some was ruled by kings, and some was ruled directly under the designation ‘provincial’ territory. Governors were appointed and special tax collectors were also appointed to collect tax from the inhabitants. There were free cities as well which were attached to the Romans as allies, while other friendly states were granted freedom as a mark of honor. The kings also relied on the advice of senators, or elders of the community, whom they chose to help them govern. Throughout their history, the Romans did not have a written constitution. Instead, they relied on customs, tradition, and laws to define what their government was and how it operated. 26

According to the early sources, Rome was ruled by a series of seven kings, none of whom were native Romans: Romulus, Numa Pompilius, Tullius Hostilius, Ancus Marcius, Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius, and Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. 27 The kings did not come in to power at once but the process was gradual. It is recorded in the books of history that in those times, a group of families, each of which was descended from a common ancestor, was called a Gens, and several of these groups bound together by common interests, common festivals, a common hearth and the worship of the same god formed a Curia. Ten Curiae made a Tribe, and three Tribes formed the early Roman state. But the Tribe did not last very long as a political division of the people, and it was the Curia that became of much greater importance, for the thirty Curiae included all the freemen of the early state. These freemen were supposed to be descended from the leading families in the small communities which had existed before Rome became a single state. As time went on and the state grew larger, these men claimed privileges for themselves because of their birth and position, and they were given the name of patricians, the patres or Fathers of the state. They sat in an assembly called the Comitia Curiata. It was they who elected the King, who on his part, chose a Senate of three hundred men to advise him, and whose business it would be to ratify the elections made by the Comitia Curiata.

The King was the chief priest, the chief ruler, and the chief general of the Roman people. As chief priest it was his duty to preserve peace and harmony between the city and the gods who watched over it. It was believed that Jupiter revealed his will by the sending of certain omens, by thunder and lightning and in the flight of birds. These omens were called the auspices and those who interpreted them the augurs. The college of augurs was held in such honor that nothing was undertaken in peace or war without its sanction. All matters of the highest importance were suspended or broken up if the omen of the birds was unfavorable. 28 As a chief ruler, he used to operate the society and its matters and as a chief general he used to lead wars and different expeditions. These three designations turned the psyche of the king and he believed himself to be a god who was unstoppable. In these circumstances when the king decided anything bizarre and malicious, he used to camouflage it under the clothing of religion and used to satisfy his evil desires in an organized way.

During the Monarchy, the kings could apparently oversee trials and pass judgment. 29 By law he had unlimited power which was called the imperium, a word which in various forms still survives today. To the Roman, this word imperium meant discipline and order in the state; it stood for the firm Roman conviction that when lawful authority had been entrusted to an individual by the members of a state, that authority needed to be absolutely obeyed. The early Roman method of electing a King ensured that every care would be taken to elect the right man, but when once elected and acknowledged as king by the people, his power was absolute. The outward symbols of this imperium were the rods borne before the King whenever he appeared in public by twelve attendants called lictors. Each lictor carried a bundle of rods called the fasces in the center of which was an axe, the symbol of the royal power over the life and death of his subjects. The lictors with their rods were introduced by the Etruscan Kings, who had also brought with them to Rome the other insignia of the kingly power: the gold crown, the ivory scepter, the ivory throne called the curule chair, and the white robe with purple border. 30

According to a few historians, the king was in theory only a magistrate to whom the people had given the management of the chief business of the state, but he was a sole magistrate holding office for life, and his powers were so enormous that they required very little straining to make his rule degenerate into a tyranny. 31

The way these rulers were chosen and how much power and authority they held is uncertain. But traditional accounts recorded by Livy and others suggest that some kind of election was held, in which the people selected male citizens, probably those who could afford to bear weapons, met periodically in an assembly and either chose or ratified nominees. More importantly, those chosen had to be ratified by the heads of the leading families (the Roman ‘fathers’, or patres). The Monarchy finally came to an end in 509 B.C. According to Livy, when King Tarquin the Proud was away from the city, the Roman fathers, meeting as the Senate, declared his rule null and void; soon afterward they set up a new government based on republican ideals. 32

Fall of the Monarchy

There were hundreds of cases of rapes, sexual harassments, exploitations and murders which are recorded and millions are unrecorded in the history of Roman monarchs but the rape case of King Sextus brought the actual downfall of monarchy in Rome. One day, he met Lucretia, a beautiful young lady while she was spinning amid her handmaids. Few days later, he entered her chamber with a drawn sword threatening that if she did not yield to his desires, he would kill her and lay by her side a slave with his throat cut, and declare that he had killed them both for adultery. Fear of such a shame forced Lucretia to consent, but as soon as Sextus departed after raping her, she went to her husband and father. They found her in an agony of sorrow. She told them what had happened, enjoined them to avenge her dishonor and stabbed herself to the heart. Her father and others swore to avenge her and took her corpse to the market of Collatia. There, the people took up arms and renounced the Tarquins. Brutus summoned the people and related the deed of shame to them. All classes were inflamed with indignation and a decree was passed deposing the king and banishing him and his family from the city. Sextus fled to Gabi, where he was shortly murdered by the friends of those whom he had put to death. 33 Hence the years of monarchy ended at Rome.

Roman Republic (509-31 B.C.)

When the monarchy came to an end, the city was governed by an oligarchy. 34 The last king of Rome was an Etruscan, called Tarquin the Proud. He offended Rome’s nobles, so they drove him out. Then, in around 510 B.C., they set up a new form of government, called a Republic (affair of the people) which served its purpose well for some four centuries. But its final century was one of increasing chaos and disorder. 35

Rome was now governed by annually elected magistrates, the most important being two consuls who were heads of state. The consuls ruled with the advice of the Senate, an assembly of around 300 serving and ex-magistrates. Every adult male citizen had the right to vote for the magistrates. Since a magistrate’s work was unpaid, only the richest could afford to stand for election, 36 but after being elected as a head of the state they used the power of the state to increase their wealth.

The Roman Republic emerged out of what one historian called ‘the ashes of the monarchy.’ Years underneath the unyielding yoke of a king taught the people of Rome that they had to safeguard against the rule, and possible oppression, of one individual. The real authority or imperium of the republic, and later empire, was to be divided among three basic elements - elected non-hereditary magistrates, a Senate to advise and consent, and popular assemblies. Unfortunately for many people in Rome, in the early stages of the Republic, power lay solely in the hands of the elite, the old-landowning families or patricians. The remainder and largest share of the city’s population - the plebeians - had few if any rights. This unequal division of power would not last very long. 37

The Republic was largely run by representatives of the people, although only free adult males, a minority of the population, could vote or hold public office. Some of these male citizens met periodically in the Roman assemblies, where they voted on new laws and also annually elected magistrates, including the consuls, praetors, censors, quaestors, and aediles. Another legislative body, the Senate, the most prestigious governmental body, held considerable influence over the assemblies and magistrates and much indirect power as a result, so the republican state was actually an oligarchy (a government run by a select group) rather than a true democracy. Still, in an age when kings and other absolute monarchs ruled almost everywhere else in the known world, the Roman Republic was indeed a progressive and enlightened political entity. Though most Romans did not have a say in state policy, many had a measurable voice in choosing leaders and making laws. These laws often offered an umbrella of protection for members of all classes against the arbitrary abuses of potentially corrupt leaders, at least until the first century B.C., when political turmoil and civil war brought about the Republic's collapse. 38

Instead of one king who held office for life, two officers, called Consuls, were elected annually from the patricians, each of whom possessed supreme power. 39 In consequence of this each consul could forbid what the other enjoined, and thus the consular commands, being both absolute, would, if they clashed, neutralize one another. 40 Hence it was very difficult for consuls to abuse their powers seriously. The Senate nominated the new consul candidates, who were then elected by the comitia centuriata. Their duties were to lead the army (each commanding equal manpower, at first two legions), to act as overall administers of the state, and to carry out the Senate's policies, especially in foreign affairs. At first, only patricians could run for the office of consul, but in 367 B.C. the privilege was extended to plebeians. 41

During the republic, male citizens could vote on legislation and in the election of government officials. Voting was done in popular assemblies, of which every citizen was a member, and voting was oral and public until 139 B.C., when secret ballots were introduced. There were four assemblies in the republic, all held outdoors. Three were known by the plural noun comitia (meetings of all citizens—plebeians and patricians), a comitium being a place of assembly. These were the comitia curiata, comitia centuriata and comitia tributa. The concilium plebis was for plebeians only. The assemblies met only to vote, not to discuss or initiate action. Legislation was initiated by a magistrate and discussed by the Senate, and was taken to one of the assemblies only for a vote. The senators therefore controlled the nature of the legislation that reached the assemblies. Laws or motions passed by the comitia were known as leges, and those by the concilium plebis were called plebiscita (decrees of the plebeians). There was no opportunity for discussion during the assemblies, but very often informal public discussions were held.

In the republican days, provinces were administered by governors appointed by the Senate and granted complete authority over tax collection, justice, and maintaining law and order. To facilitate the latter, a governor could raise and command troops; therefore, he possessed the imperium (power to command), although it was valid only in his own province. A governor was assisted by a quaestor (financial official) and a staff of formal advisers (legati) and informal advisers (amid or friends). It was common for a consul or praetor to become a provincial governor (with the title of proconsul) at the end of his consulship or praetorship. 42

By the end of the republic many Roman citizens did not live in or near Rome and so would have had difficulty exercising their right to vote. The comitia continued in existence until the 3rd century A.D. but had lost their functions by the late 1st century. 43

Roman Empire (27 B.C. - 476 A.D.)

At the end of the civil wars in 31 B.C., Octavian (later Augustus) was in complete control of the empire. While Octavian’s position was unassailable, his legal position was difficult. In 27 B.C., he handed over the state to the Senate. 44 Some dynasts, tribal chieftains and priestly rulers were also subject to the Romans; these people regulated their lives along their traditional lines. But the provinces, which were differently divided at various times, were arranged in a special manner under Caesar Augustus. For when his country entrusted him with supreme authority in the Empire and he became established as lord for life of peace and war, he divided the whole territory into two parts, assigning one to himself, the rest to the people. 45

The Roman realm that existed from the accession of Augustus in 27 B.C., following the collapse of the Roman Republic, until the emperor Romulus Augustulus was deposed in A.D. 476. The term Empire also refers to this roughly five-hundred-year long time period. At its height in the 2nd century A.D., the Empire encompassed about 3.5 million square miles and 100 million people. Its government was mainly autocratic in nature, as a succession of emperors, supported by the army, held most of the power. 46

Under the empire, governors were paid a salary, and their wives could accompany them to the provinces. The Senate retained nominal control of the peaceful (public) provinces and appointed governors, generally on an annual basis. The governors were proconsuls, usually recruited from ex-consuls for Africa and Asia (consular governors) and from ex-praetors for the rest (praetorian governors). The governors were still accompanied by a quaestor and legati. A law introduced by Pompey in 52 B.C. and reintroduced by Augustus stipulated that five years had to elapse between holding a qualifying magistracy and being appointed governor. This was largely to curb bribery and corruption.

All other provinces were under a single proconsul, who was the emperor, and was not bound by a time limit in office. Governors of imperial provinces were appointed by the emperor and were his legates with pro-praetorian power (legati Augusti pro praetore). They were recruited from ex-consuls in provinces where there was more than one legion and from ex-praetors elsewhere, and were not bound by the five-year rule. Roman Egypt was governed by a prefect (praefectus Aegypti) of equestrian rank, because no senator was allowed to enter Egypt without the emperor’s permission, fearing that an ambitious senator would cut off the grain supply to Rome. Some unimportant imperial provinces also had equestrian prefects or procurators as governors. Increasingly, governors were equestrian with a military background. Imperial provinces did not use quaestors as financial secretaries but rather fiscal procurators of equestrian rank (as opposed to the procurators, who were governors). 47

Government Institutions

SenateSenate was the chief legislative body of the Republic and a repository of tradition and great prestige for both the Republic and Empire. Originally, the Senate was the advisory council to the Roman kings. After the creation of the Republic, circa 509 B.C., it served, in theory, the same function for Rome's elected magistrates. However, it was at first composed exclusively of patricians (landed aristocrats), who held their positions for life; patricians came not only to dictate most of the policies of the consuls, but also, through the use of wealth and high position, indirectly to influence the way the members of the assemblies voted. Thus, except under extreme circumstances, the Senate held the real power in the Republic, especially in its last two centuries. 48

A senate in the early times was always regarded as an assembly of elders, which is in fact the meaning of the Roman senatus, and its members were elected from among the nobles of the nation. 49 The middle and late republic a man was automatically admitted to the Senate for life once he had been elected by the comitia or concilium to his first magistracy. He was expelled only if found guilty of misconduct. There were originally 100 members, which was increased to 300, then to 600 in 80 B.C., and to 900 under Julius Caesar. 50 Regarding the minimum age for a senator, lex annalis of the tribune Villius states that the age fixed for the quaestorship was 31. However, Augustus at last fixed the senatorial age at 25, which appears to have remained unaltered throughout the time of the empire. 51

A man was eligible to join the Senate after he had served in his first magistracy, which was usually the first office in the cursus honorum (course of offices), that of quaestor. So, the body became in essence a group of ex-magistrates. In mid-republican times, the qualification of belonging to the patrician class was dropped and plebeians were allowed to join, although they remained in the minority. Senators received no pay, but this posed no hardship because virtually all were rich property owners and they used to earn more money by using their relationships and sources especially in illegal transactions. A senator could be removed only for committing some serious offense against the state, in which case the censors, who kept the lists of senators, replaced him. Meetings of the Senate could be held on any of the grounds within the capital that had been consecrated by Rome's chief priests, but most often the senators met in the Senate House (Curia Hostilia), located in the northwest corner of the main Forum. 52

The Senate was formally a body that advised magistrates, but from the 3rd century B.C. it increased its influence and power, particularly through the crisis of the Second Punic War. Among other work, it prepared legislation to put before the assemblies, administered finances, dealt with foreign relations and supervised state religion. In the 2nd and 1st centuries B.C. the Senate was the virtual government of Rome, having great influence and control over the assemblies and magistrates. It could not make laws but issued decrees (known as decreta or senatus consulta). The final decree of the Senate was the final resort for crushing political threats, last employed in 40 B.C. It authorized magistrates to employ every means possible to restore order. Senators had to have a private income as they received no payment. During the republic, the most important activity in adult life for the small group of families who constituted the senatorial class was the pursuit of political power for themselves, their family and friends. A boy’s rhetorical education and a young man’s activities in the law courts were preparations for a political career. Men would try to win the election to their first magistracy in their early 30s. Friendships, marriages and even divorces were often a matter of political convenience. A politician was expected to greet everyone warmly and by name, and was assisted by a slave called a nomenclator whose duty it was to memorize names and identify people.

Only a small percentage of the population was deeply involved in politics. Rivalry was intense and the political campaigns were bitter. Because elections were held every year, the process of campaigning was virtually unending. Political slogans were painted on walls of buildings at Pompeii and presumably in other cities. Campaigns were also expensive, with bribery (ambitus) and corruption commonplace. Even if not running for office, a man was expected to campaign for family and friends. Among the senators was an exclusive group of nobiles (well known) whose ancestors (patrician or plebeian) had held a curule magistracy (later a consulship only). Up to the 1st century B.C. few men outside these families reached consular rank. Political alliances or factions (factiones) were common within these families, and various methods were used to undermine opposition factions. A novus homo (new man) was the first man in a family (such as Cicero) to hold a curule magistracy, especially a consulship.

In the empire the term nobiles was applied to the descendants of republican consuls. After the Gracchi, the politicians were divided into two opposing groups. The populares (on the side of the people) were reformers who worked through the people rather than the Senate. Their political opponents called themselves the optimates (best class) and were the larger and conservative part of the Senate.

Meetings of the Senate were attended by senators, magistrates and the members called flamen dialis 53 only, although the public could gather by the open doors in the vestibule. Meetings with Curia Hostilia were conducted in the northwest corner of the Forum, but they could also be conducted at any public consecrated place within 1.6 km (one mile) of Rome. Senators sat on benches (subselli) down the long sides of the building in no fixed order. 54

The senate suffered degradations in the 1st century B.C. at the hands of Sulla and Julius Caesar, and by the reign of Augustus (27 B.C.-14 A.D.) it was a mere instrument in the hands of the emperors. Although there would be moments of achievement during the imperial epoch, the Senate's era of glory had passed. As the first emperor, Augustus was shrewd enough to retain to the furthest possible degree the trappings of the Republic, including the Senate. Once he had cleansed it and made it his own through Adlectio (enrollment) and censorial privilege, he returned to its extensive powers. The Senate was still in charge of the Aerarium (state treasury), governed or administered all provinces outside the control of the emperor, including Italy, retained the privilege of minting all copper coinage, and eventually had legal and legislative rights. One by one, however, its original duties were curtailed or usurped by the rulers. The aerarium was one of the first to go as the Senate grew utterly dependent upon the goodwill of the Princeps. The emperor heeded the advice of the senators selectively and even the election of magistrates, which passed to the Senate from the people, was merely a reflection of imperial wishes. A serious blow to the Senate was the degree of supremacy exercised over the selection of its members by the emperors. As the Princeps Senatus, the ruler applied the gift of adlectio to appoint senators, while all candidates for the senatorial class were first approved by the palace. Nevertheless, the Cursus Honorum was intact, as senators were enrolled only after a long and possibly distinguished career in the military or government. High posts throughout the Empire were often filled with them, a situation concretized by the transformation of the senatorial class into a hereditary one. 55

Dictatorship

Despite the advantages of consular collegiality, unity of command in military emergencies was sometimes necessary. Rome’s solution to this problem was the appointment of a dictator in place of the consuls. According to ancient tradition, the office of dictator was created in 501 B.C., and it was used periodically down to the Second Punic War. The dictator held supreme military command for no longer than six months. He was also termed the master of the army (magister populi), and he appointed a subordinate cavalry commander, the master of horse (magister equitum). The office was thoroughly constitutional and should not be confused with the late republican dictatorships of Sulla and Caesar, which were simply legalizations of autocratic power obtained through military usurpation. 56

Civil Servants

In the republic the only civil servants were the treasury scribes (scribae) who assisted the quaestor. Some went to the provinces each year to assist the governor while the rest stayed at Rome. Under the empire scribae remained the only civil servants of the Senate, while a huge civil service was established under the emperor. Many of the clerical positions were staffed by freedmen and slaves, especially Greeks, and often other posts were held by equestrians. Many of the civil service posts encroached on old magistracies. The praefectus annonae was an equestrian in charge of the grain supply from the reign of Augustus, taking over the role of aediles. Augustus also established boards (curatores) to take over the functions of many magistracies. They included curatores viarum (keepers of roads) who were in charge of maintenance of Italian roads, curatores operum publicorum (keepers of public works) who were in charge of public buildings and curatores aquarum (keepers of the water supply) who were in charge of Rome’s aqueducts. 57

Fall of Rome

Today, most historians favor two broad views of Rome's decline and fall. The first stresses military factors, the most crucial being the accumulative effects of one devastating barbarian incursion after another and the steady deterioration of the Roman army, which became less and less capable of stopping the invaders. The second view (which does refute or preclude the first) contends that only Rome's political and administrative apparatus fell in the 5th century, and that many aspects of Roman institutions, culture, and ideas survived, both in the Byzantine Empire in the east and in the barbarian kingdoms in the west. Through such continuity, Roman language, ideas, laws, and so forth survived to shape the modern world. 58

According to James W. Ermatinger, the real political problem, succession, was not unique to this period but to all dynasties. Rome never established an efficient, stable, and beneficial means of succession. Diocletian attempted to solve this problem by adoption, as had the Antonines a century and a half earlier, but Constantine and a strong prejudice in favor of dynastic rule overrode this sensible plan. The problem of dynastic succession, evident since Augustus, constantly plagued Rome, and likely caused some weakness. However, even here, the same problem existed in the East, continuing for the next millennium, until Constantinople fell. Thus, poor leadership and issues of succession cannot be singled out as the cause of the Roman Empire’s collapse. 59

Even the ‘great’ political system of ancient Rome could not sustain itself. As time went on, Rome had problems that the Senate was not able to solve and these problems went from bad to worse. One of the problems was that the government kept running out of money. They needed money to pay the military, pave roads, and to satisfy their luxurious lifestyles. They kept raising taxes, but the people were taxed out. They didn't have any more money to give and could not afford to bear the brutalities inflicted by their cruel rulers. Rome suffered from graft and corruption amongst elected officials as well. Crime was terrible. It was unsafe to walk on the streets of Rome. Things were out of control, hence with time, the provinces of Rome started to break off one by one and gradually the great empire of kept shrinking till nothing but small pieces of land were left.

- 1 John H. Haaren & A. B. Poland (1904), Famous Men of Rome, American Book Company, New York, USA, Pg. 203.

- 2 W. Lucas Collins (1871), Cicero, William Blackwood and Sons, London, U.K., Pg. 2-3.

- 3 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/biography/Cicero Retrieved: 08-12-2018

- 4 J. L. Strachan-Davidson (1894), Cicero and the Fall of the Roman Republic, G. P. Putnam & Sons, London, U.K., Pg. 2.

- 5 Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Online Version): https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ancientpolitical/#CicLif: Retrieved: 08-12-2018

- 6 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): https://www.ancient.eu/Julius_Caesar/: Retrieved: 11-02-2019

- 7 Isidore Singer (1902), The Jewish Encyclopedia, Funk and Wagnalis Company, New York, USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 314.

- 8 James Orr (1915), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, The Howard – Severance Company, Chicago, USA, Vol. 1, Pg. 332.

- 9 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): https://www.ancient.eu/augustus/: Retrieved: 10-12-2018

- 10 C. Suetonius Tranquillus (1796), The Life of the Twelve Caesars (Translated by Alexander Thomson), G. G. & Robinson, London, U.K., Pg. 119.

- 11 C. Suetonius Tranquillus (1796), The Life of the Twelve Caesars (Translated by Alexander Thomson), G. G. & Robinson, London, U.K., Pg. 376-377.

- 12 Robert Graves (1934), I, Claudius: From the Autobiography of Tiberius Claudius, Born 10 B.C – Murdered and Deified A.D. 54, The Modern Library, New York, USA, Pg. 3.

- 13 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version):https://www.ancient.eu/claudius/: Retrieved: 08-12-2018

- 14 F. R. B. Godolphin (1934), Classical Philogy: A Note on the Marriage of Claudius and Agrippina, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA, Vol. 29, Article: 2, Pg. 143.

- 15 James Orr (1915), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, The Howard – Severance Company, Chicago, USA, Vol. 1, Pg. 666.

- 16 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version):https://www.britannica.com/biography/Nero-Roman-emperor Retrieved: 06-12-2018

- 17 The Catholic Encyclopedia (Online Version): http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10752c.htm Retrieved: 06-12-2018

- 18 Don Nardo (2002), The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Greenhaven Press Inc., California, USA, Pg. 45-46.

- 19 The Catholic Encyclopedia (Online Version):http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08578b.htm Retrieved: 22-12-2017

- 20 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version):https://www.britannica.com/biography/Justinian-I Retrieved: 28-01-2019

- 21 Carroll Moulton (1998), Ancient Greece and Rome, Simon & Schuster, New York, USA, Vol. 4, Pg. 16-17.

- 22 A. E. Astin (1989), The Cambridge Ancient History, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., Vol. 8, Pg. 167-168.

- 23 Michael Burgan (2009), Empire of Ancient Rome, Chelsea House Publishers, New York, USA, Pg. 81.

- 24 Image Publishing Authors (2014), All about History: Book of Ancient Rome, Imagine Publishing Ltd., Dorset, U.K., Pg. 31.

- 25 Don Nardo (2002), The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Greenhaven Press Inc., California, USA, Pg. 134.

- 26 Michael Burgan (2009), Empire of Ancient Rome, Chelsea House Publishers, New York, USA, Pg. 83.

- 27 Carroll Moulton (1998), Ancient Greece and Rome, Simon & Schuster, New York, USA, Vol. 4, Pg. 4.

- 28 Dorothy Mills (1937), The Book of the Ancient Romans, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, USA, Pg. 57-59.

- 29 Don Nardo (2002), The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Greenhaven Press Inc., California, USA, Pg. 128.

- 30 Dorothy Mills (1937), The Book of the Ancient Romans, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, USA, Pg. 57-59.

- 31 William Smith (1913), A Smaller History of Rome, John Murray, London, U.K., Pg. 16-17.

- 32 Don Nardo (2002), The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Greenhaven Press Inc., California, USA, Pg.134-135.

- 33 William Smith (1913), A Smaller History of Rome, John Murray, London, U.K., Pg. 29-30.

- 34 Paul Erdkamp (2013), The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Rome, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., Pg. 21.

- 35 Anthony A. Barrett (1999), Agrippina: Sex, Power and Politics in the Early Empire, Routledge, London, U.K, Pg. 1.

- 36 Peter Chrisp (2006), E. Explore Ancient Rome, Dorling Kindersley Limited, London, U.K., Pg. 12.

- 37 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): https://www.ancient.eu/Roman_Government/: Retrieved: 05-12-2018

- 38 Don Nardo (2002), The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Greenhaven Press Inc., California, USA, Pg. 138.

- 39 Robert F. Pennell (1894), Ancient Rome: From the Earliest Times Down to 476 A.D, Allyn and Bacon, Boston, USA, Pg. 18.

- 40 C. Bryans & F. J. R. Hendy (1911), The History of the Roman Republic, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, USA, Pg. 41.

- 41 Don Nardo (2002), The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Greenhaven Press Inc., California, USA, Pg. 127-128.

- 42 Don Nardo (2002), The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Greenhaven Press Inc., California, USA, Pg. 136.

- 43 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2004), Handbook to life in Ancient Rome, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 39-40.

- 44 Ibid: Pg. 113-114.

- 45 Barbara Levick (1985), The Government of the Roman Empire, Routledge, New York, USA, Pg. 9-10.

- 46 Don Nardo (2002), The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Greenhaven Press Inc., California, USA, Pg. 131.

- 47 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2004), Handbook to life in Ancient Rome, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 46.

- 48 Don Nardo (2002), The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Greenhaven Press Inc., California, USA, Pg. 138-139.

- 49 William Smith (1875), A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, U.K., Pg. 1016.

- 50 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2004), Handbook to life in Ancient Rome, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 40.

- 51 William Smith (1875), A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, U.K., Pg. 1019.

- 52 Don Nardo (2002), The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Greenhaven Press Inc., California, USA, Pg. 139.

- 53 Flamen, the name for any Roman priest who was devoted to the service of one particular god and who received a distinguishing epithet from the deity to whom he ministered. [William Smith (1875), A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, U.K., Pg. 540.

- 54 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2004), Handbook to life in Ancient Rome, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 40-41.

- 55 Mathew Bunson (1994), Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 903-904.

- 56 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/place/ancient-Rome Retrieved: 14-02-2019

- 57 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2004), Handbook to life in Ancient Rome, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 45

- 58 Don Nardo (2002), The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Ancient Rome, Greenhaven Press Inc., California, USA, Pg. 272.

- 59 James W. Ermatinger (2004), The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Green Wood Press, Connecticut, USA, Pg. 56-57.