Life Style of Ancient Rome – Society, Culture & Habits

Published on: 26-Jun-2024(Cite: Hamdani, Mufti Shah Rafi Uddin & Khan, Dr. (Mufti) Imran. (2020), Life Style of Ancient Rome, Encyclopedia of Muhammad  , Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 323-366.)

, Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 323-366.)

Around 2000 years ago, Rome was at the center of a huge empire that stretched from Scotland to Syria. The empire was built on the backs of its citizens - the unsung people who lived a relatively quiet existence, and who are often ignored by history. The contemporary western world seems so impressed by the lifestyle of this civilization that it made it their way of life.

Palatine Hill was one of the seven hills along the Tiber River. The Tiber River ran into the Tyrrhenian Sea. There, a little village began as a farming community. This is where the city of Rome was started around 753 B.C. The twin brothers named Romulus and Remus founded the city of Rome. Over hundreds of years, the city grew to become the Roman Empire. That empire included all of Italy and about half of Europe. It also included the northern part of Africa and a large part of the Middle East. 1 In a history of over 1200 years, Rome grew from a primitive settlement on the Tiber’s banks into the most powerful empire of the ancient world. Rome provided Europe, much of the Middle East, and North Africa with a unified social, legal, and administrative system, as well as a common language that was the basis of many European tongues thereafter. The Romans quantified time and the calendar, they gave Europe a superb road network, concrete bridges, a postal system, central heating, piped fresh water, enormous public baths, and monumental civic buildings. In the Roman world, we see the culmination of ancient Eurasian culture in about every respect that can be imagined. 2

Population

Ancient historians state that in the late 6th century B.C. the king, Servius Tullius, conducted the first census of the Roman people, classifying them according to wealth for voting purposes and eligibility for military service, with a minimum property qualification established for the army. 3

In the second half of the 5th century B.C. Rome was still an aristocratic community of free peasants, occupying an area of nearly 400 square miles. 4 In the first phase, up to about 400 B.C., the city-state itself grew up to a point where participatory institutions could still work in practice and a total population of fewer than 100,000 people. Rapid expansion from 400 to 270 B.C. brought dramatic changes. Although only vague estimates are feasible, it appears that the number of citizens more than quadrupled via mass enfranchisement between 350 and 290 B.C. while the number of allies quintupled around 200,000 to about one million. From 290 and 225 B.C., the citizenry grew by another 50% while the number of allies more than doubled. In brief, within 150 years Rome moved from a city-state with a core of 100,000 -150,000 citizens and a penumbra of some 200,000 allies to a multi-layered system comprised of a core of up to 300,000 citizens, an inner periphery of another 600,000 citizens, and an outer periphery of over 2 million Italian allies. 5

Reliable information about the population are the figures for totals of citizens registered under Augustus and Claudius. These suggest that around A.D. 14, there were about 5 million free inhabitants of Italy, to which some demographic analysts conjecture that a population of 2 to 3 million slaves need to be added. Rome had a population of between 500,000 and 1 million, possibly around 800,000 in the time of Augustus, rising to 1 million in the early 2nd century. 6 Many of inhabitants came from different lands, hoping to make their fortunes in the city they saw as the Centre of the world. 7 The population of the Roman Empire has been estimated at between fifty and sixty million. Yet the army maintained by the Roman Empire was only thirty legions strong in the later second century, about 150,000–180,000 men, with a force of about 253,690 auxiliary troops and sailors. 8

Race

The Roman race was strangely mixed. The principal element was Latin, and originally from Alba; but these Albans were composed of two associated, but not confounded, populations. One was the aboriginal race, real Latins. The other was of foreign origin, and was said to have come from Troy with Aeneas, the priest-founder; it was, to all appearance, not numerous, but was influential from the worship and the institutions which it had brought with it. At Rome all races were associated and mingled; there were Latins, Trojans, and Greeks; there were, a little later, Sabines, and Etruscans. 9

Life Expectancy

Life expectancy at that time was shorter than today, although there is evidence for people surviving to an old age, especially within the upper class. Infant and child mortality was high, as was the incidence of mortality due to childbirth. From time to time the population was severely reduced by outbreaks of disease, such as a plague in the late 2nd century. 10

Average life expectancy at birth was most likely between 22 and 25 years, and perhaps nearly half the babies born died before their fifth birthday. Children who survived to their tenth birthday had on average a life expectancy of some 36 to 38 additional years, taking the surviving female past menopause and the male to nearly age 50. Life span among Romans was apparently similar to our own, yet only a little over one percent of the Roman population reached their eightieth birthday, and people were dying at all ages. 11

Calendar

Three types of calendars were in use at several times among the Romans, which owe their origin to Romulus, Numa, and Julius Caesar. 12 Macrobius credits Romulus with establishing the first Roman calendar, in which the year began in March. 13

Ten Month Calendar of Romulus (753 B.C.)

The original Roman calendar (year of Romulus) was an agricultural 10-month year. There were 10 irregular months (totaling 304 days) from March to December. The names of the months originated in this first calendar, with an uncounted gap from December to March when no agricultural work was possible. 14 Romulus divided his year into ten months, where some months consisted of twenty days, some of thirty-five, and some of more. But he settled the number of days with a great deal more equality, allotting thirty-one days to March, May, Quintilis, and October and thirty days to April, June, Sextilis, November, and December; making up in all three hundred and four days. 15

Numa’s Reforms in Calendar (713 B.C.)

Numa Pompilius (715-673 B.C.) was a little better acquainted with the celestial motions than his predecessor, therefore, he added the two months of January and February; the first of which he dedicated to the god Janus; the other took its name from februo, to purify, because the feasts of purification were celebrated in that month. To compose these two months, he put fifty days to the old three hundred and four, to make them answer the course of the moon; and then took six more from the six months that had even days, adding one odd day more than he ought to have done, merely out of superstition, and to make the number fortunate. However, he could only get twenty-eight days for February and therefore that month was always counted unlucky. 16

Hence Numa’s year consisted of all 12 months, where March, May, July, October had 31 days, and the rest 29, except February which had 28. All the months therefore had an odd number of days, except the one which was especially devoted to purification and the cult of the dead; according to an old superstition, probably adopted from the Greeks of Southern Italy that odd numbers were of good omen and even numbers were of ill. 17

Names of months were adjectives relating to mensis (month): Januarius, Februarius, Martius, Aprilis, Maius, Junius, Quintilis (fifth month), Sextilis (sixth month, renamed Augustus in 8 B.C. after the emperor Augustus), September (seventh month), October (eighth month), November (ninth month), December (tenth month). 18

Martius (March) was the first month of the year. 19 But in 153 B.C., for reasons of administrative convenience, the beginning of the civil year was transferred from 1 March to 1 January, when the newly elected magistrates entered office. The Roman farmers would not feel much change at the end of December, since the real break in the agricultural year came in March after a period of comparative rest. 20

Julian Calendar (46 B.C.)

Before Julius Caesar reformed the Roman calendar, it was the job of the priests to keep the human calendar in line with the solar year. Unfortunately, they were not very good at doing this. They randomly added ‘leap’ days until the seasons were about 80 days out of kilter with the calendar months. 21 Julius Caesar was the first that undertook to remedy this disorder; and for this purpose, he called the best philosophers and mathematicians of his time. In order to bring matters right, he required to make one year of fifteen months, or 445 days. 22 The new system, Caesar decreed, began on January 1, 45 B.C. As for the year in which the calendar was being put into operation, 46 B.C., that was lengthened by three months, or by 90 days, to a total of 445 days, to ensure an astronomically correct transition. 23 The Julian calendar is acknowledged and runs alongside the others, particularly in the worlds of business and politics. 24

Days in a Month

The days were not numbered from the beginning of a month but from three special days called the Kalends (first of the month), the Nones (ninth day), and the Ides (13th day, or 15th in a month of 31 days). The Roman month was very organized and days were divided between four main types, with citizens told what activity may take place on each type of day. On a Dies Comitalis citizens could vote on political matters. On a Dies Fastus the law courts operated and legal matters were handled, including marriages. On a Dies Endotercisus legal matters took place in the morning and voting in the afternoon. On a Dies Nefastus neither voting nor legal matters were allowed. Market days (Dies Nundinae) occurred every seven days, whatever its type unless it was reserved for religious purposes. On market days agricultural produce was taken to markets. It was also a day for men of leisure to meet and exchange news in the Forum. There were days on which activity was restricted because they were unlucky. Such ‘black days’ (Dies Atri) were not usually marked on calendars. They were tainted by the anniversaries of past disasters in war, and on this day, the Romans remembered and mourned the dead. 25

Weeks

From earliest times, a market day (Nundinae) occurred every ninth day, according to the Roman method of inclusive reckoning. It was a day of rest from agricultural labor and a time to bring products to market. The intervening period was a Nundinum. The seven-day period was used in the east, particularly by astrologers in Hellenistic times, with some days receiving the names of the planets. The earliest reference to a seven-day period at Rome is in the time of Augustus (27 B.C.–A.D. 14), and it was gradually adopted during the empire. 26

By the middle Republic, every eighth day was a market day. This was marked on the calendars with a recurring cycle of the letters A to H, beginning on 1st January and continuing through the year. The Romans took no account of the months in aligning their continuous civic weekly cycle on a solar, not lunar year. 27

Time Measuring Devices

The day was divided into 12 hours of night and 12 hours of day, so that a daylight hour was not the same length as a night hour (except at an equinox) and varied from month to month. A daylight hour in midwinter was about 45 minutes, and in midsummer, one and a half hours. The length also varied with latitude. Midnight was always the sixth hour of night, and midday the sixth hour of day. The time of day was referred to in terms such as “first hour” (the hour after sunrise), “twelfth hour” (the hour before sunset) and “midday” (meridies). Ante meridiem (A.M.) was before midday (morning), and post meridiem (PM) was after midday (afternoon). Clocks (horologia) were used—the shadow clock or sundial and the water clock. Shadow clocks in the form of sundials (solaria) were introduced to Rome in the 3rd century B.C. These clocks had the disadvantage of relying on sunshine, needed different scales according to the latitude, and seasonal correction, and could not be used at night. 28 Time was perpetually fluid or, if the expression is preferred, contradictory. The hours were originally calculated for daytime; and even when the water-clock made it possible to calculate the night hours by a simple reversal of the data which the sun-dial had furnished, it did not succeed in unifying them. 29 At home, people used candles calibrated by marks representing the hours. In theory, depending on the time of year, it would take an hour for the flame to burn down between two marks. In practice, they were very inaccurate. Hourglasses suffered from the same problem of constantly changing hour lengths during the year. Water clocks, or clepsydrae, were more useful because they worked at night as well and seasonal adjustment was achieved by a clever mechanical system. 30

Social Classes

Roman social order was multi-dimensional with various coexisting social fields and complex hierarchies. Status was measured by sets of different criteria, as birth, gender, wealth, education, ethnicity, skill, etc. each contributing to assigning specific social positions. Purity, piety, trustworthiness etc. was not important for them at all. They were the followers of wealth and power, which was their main concern throughout their life. At the top – at the municipal, provincial and imperial level – stood the aristocracy, whose status was derived from and was expressed by the con-junction of different status criteria: wealth, education, political and/or religious functions which were mostly spoiled in their nature, birth and so forth. 31 At the top of the society were wealthy landowners from prominent families, whose privileged place was recognized by the state and marked by special clothing. At the bottom were peasants, tenant farmers, the urban poor, and slaves. Though the terms of respect varied from period to period, the subordination of the lower classes was found in every Roman age. Roman literature reveals that there was little to no support for the idea of equality, and no one gave serious thought to changing the class system. Early Roman society was divided into two orders, the Patricians (members of the upper class) and the Plebeians (ordinary Roman citizens).

In the early republic, the Patrician class dominated Roman society which pertained to a closed circle of privileged families and held a monopoly on Roman high political offices and priesthoods. According to Roman tradition, the patricians were descendants of the 100 men who had been in the first Roman Senate and membership in the patrician class was inherited. 32

Patricians

A strict social order developed in the early days of Rome, when the kings called together the oldest families (patres) for advice and counselling. The heads of the families formed the Senate (from the Latin for senes, old men) and thus constituted, with their families, the first class of the Roman society. With the expulsion of the kings, the Republic was founded, with political power resting in the hands of Patricians, who controlled not only the Senate but also the high positions of government. 33

After the expulsion of the kings, who may have been some check on patrician control, the patricians attempted to keep sole possession of magistracies, priesthoods, and legal and religious knowledge; there was even a prohibition against intermarriage with plebeians in the law of the Twelve Tables. Towards the end of the early republic, patricians retained exclusive control only of some old priesthoods, the office of interrex, or interim head of state, and perhaps that of princeps senatus, or senate leader. In the late republic (i.e., to the 1st century B.C.) distinctions between patricians and plebeians lost political importance; some patricians became plebeians by adoption. During the empire (after 27 B.C.), patrician rank was a prerequisite for ascent to the throne, and only the emperor could create patricians. Necessary for the continuation of ancient priesthoods, patricians had few privileges other than reduced military obligations. After Constantine’s reign (306–337), patricius became a personal, nonhereditary title of honor, ranked third after the emperor and consuls, but the title bestowed no peculiar power. 34

Plebians

All Roman citizens excluded from the patrician class—from peasants and artisans to landowners—belonged to the large class of plebeians. 35 In the early years of the Republic, the plebeians or plebs were not full citizens because they were not allowed to hold public office, sue in court, serve in important priesthoods, or become senators. Most plebs became part of the legal and social underclass known as the humiliores, whose members received harsher punishments for the same crimes committed by upper-class people. 36 According to law and custom, the Plebs could not enter the priestly colleges, hold magistracies or marry into the class of the patricii. They were considered as livestock and were dealt as aliens. Their status in the eyes of patricians was like garbage, and the patricians used to exploit their rights because of their status and hierarchy. However, they did command certain rights, including lower ranks in the army to be protected by their rebellions.

The status of the plebeians was greatly aided by increased organization, to the extent that they could challenge the patricians as a legitimate order. 37 The plebeians challenged the patrician monopoly on privileges. Eventually, plebeians gained access to nearly all the important political offices and priesthoods formerly held by the patricians. The greatest success for the plebeians came with the passage of the Licinian-Sextian laws in 367-366 B.C. Plebeians gained the right to become Consuls, the highest officials during the Roman Republic. The wealthiest plebeians thus joined the patricians in forming a small and exclusive group that dominated Roman politics thereafter: the ‘patricio-plebeian’ nobility. 38

Equestrians

These two social orders were joined in time by the Equestrians, who belonged both to the Patricians and the Plebeians. Importantly, the Equestrians fulfilled the needed task of acting as bankers and economic leaders. They received into their ranks numerous noblemen who opted for membership and commoners who could afford the large fees necessary for admission. They had access to all classes, were historically the most flexible and had long-standing ties to business and finance, the Knights were perfectly positioned to receive the patronage of the emperors. By the 2nd century A.D., they began to take over vital roles in affairs of the Empire. Because of the infusion of new blood, the Equestrians were constantly drawing off members of the next class, the Plebeians. The departure of members of this group to the Equestrians was probably always welcomed, especially by the new knight's family. 39 During the Republic the Equites served as the middle class, situated socially between the Senate and the common Roman citizen. During the Empire they were reorganized and used to occupy an increasing number of posts in the imperial bureaucracy. 40

Slaves

The word ‘servant’ cames from the Latin word servus, meaning a slave. 41 The civilization of the Roman world was enjoyed by the few at the expense of the majority. Wealth and resources were distributed unequally and there was relatively little social mobility. There was a large labor force of slaves and of poorly paid free labor. Slaves and their children were not considered human beings, but the property of their owners was traded like any other commodity. They were sold or rented out by slave dealers, or they could be bought and sold between individuals. 42 Their position was not much better than wild animals.

Slavery played such a major role in ancient Rome that these early civilizations can accurately be called slave societies. In addition to providing most of the labor in Rome, slaves made up a large percentage of the population. Perhaps a quarter to a third of the population of classical Athens were slaves. During the Roman wars of conquest, the Romans captured and enslaved hundreds of thousands of prisoners. By the end of the Roman Republic, Italy had more than 2 million slaves, which was more than a third of the population. 43

Slaves came from three groups of people—those captured in war, those abandoned by their parents at birth, and those descended from slaves. All three types were considered outsiders by their communities and were allowed to live only by being enslaved. Although debtors were sometimes sold into slavery, they had to be sold abroad. According to Roman law, a freeborn Roman could not be enslaved. If a slave could prove in a court of law that he or she had been born free, the individual had to be freed. 44

An important factor behind the institution of slavery was poverty. It was for a very good reason that the self-sale of impoverished citizens into slavery is named first among the different ways of enslavement in Roman civil law. The burden of mounting debts and the risk of starving to death was great enough to prefer a life in slavery to a free existence below the margin of subsistence. 45

Debt slavery also existed in Roman history. Since Romans were not permitted to sell their fellow citizens into slavery, insolvent debtors had to be sold trans Tiberim, i.e. beyond the borders of the city-state. This practice was prohibited at the latest by the lex Poetelia Papiria of 326 B.C. Even earlier, debtors had delivered themselves into the hands of their creditors as serfs (nexi), to work off their debts as manual labourers. 46 Dealers obtained slaves as prisoners-of-war and also from pirates and through trade outside Roman territory. Parents also sold their children, particularly to pay debts, and slaves were obtained as well from unwanted children left to die. 47 Another source of slave labour was enslavement as a form of legal punishment. It was routinely and systematically applied to members of the lower strata of the society (humiliores), specifically as a punishment for capital offences. 48

In the eyes of the law, a slave was the absolute property of his master; he could not marry without his consent and his master could inflict any kind of punishment on him that he chose or even kill him. 49 Roman laws regarding slaves were designed to protect the value of the property to the owner; the laws did nothing for the interests of the slave. If a court awarded compensation for an injury to a slave, the money went to the master. Similarly, because the slave was the master’s property, the slaveholder was responsible for any crimes or mischief the slave committed. Slaves could not appear in court on their own behalf, nor could they bring any complaint against their masters. If testimony from a slave was needed in a court case, the court was permitted to torture the slave to obtain the desired testimony. If a Roman wanted to put his slave to death, he was expected to follow a certain procedure. He first had to discuss the matter with a group of household friends, who served as a court. If the slaveholder was still determined to kill the slave, he had to turn the slave over to a government official for execution. Although masters were discouraged from killing their slaves, they were free to punish them as much as they wanted. 50

Slavery itself was a manifestation of a constant demand for a labour force and there were traditionally only few professions suited to women, such as wet nurses (nutrices), hairdressers (ornatrices) and walking companions (pedisequae). Even in personal households, cooks (coci), attendants (pueri), chamberlains (cubicularii) and dressers (a veste, vestiarii) were all male. The same can be said for the leading positions in the textile industries (lanipendi, sometimes lanipendae), even though the lower ranks were composed of a predominantly female labour force (textrices, textriculae). Consequently, the demand for male slaves was great that the available sources reflect. 51 Slaves were employed in every form of skilled and unskilled labor. No tasks was performed solely by slaves, but they formed the overwhelming majority of workers in mining, factories and private households. They were also owned by towns and cities to undertake public works, such as road construction or maintenance of aqueducts, but slave ownership by the state was limited by the practice of contracting out many public enterprises. The agricultural labor force was more complex, though, with large farming estates worked entirely by slaves existing alongside smaller farms worked by peasants or leased to tenants. The only job barred to slaves was military service. 52

Many were forced to work in the mines. They were often chained to their work areas, and most of them died of malnutrition and overwork. 53 Mountains were hollowed out by the digging of long tunnels by the light of torches. The miners worked in shifts as long as the torches lasted, and did not see daylight for months at a time. 54 Treatment was worse in the mines and life expectancy was short. 55

The Romans used slaves to assist the Magistrates in administering public works, such as buildings, roads, and aqueducts. Some slaves who worked in the households of emperors rose to positions of great influence and power. Emperors liked to use slaves in sensitive positions because they were loyal to the emperor alone. 56 Harsh treatment was often restrained by the fact that the slave was an investment, and impairment of the slave’s performance might involve financial loss. Treatment tended to be harsher in factories, agriculture and mining, where slaves would work seven days a week with no holidays. They could also be branded or wear inscribed metal collars, so that they had little chance of successful escape. 57 This practice shows that they were not treated differently from animals.

Apuleius states that the slaves working in a mill only wore threadbare rags, some no more than a loin-cloth. As long as they could survive and work, owners did not have to trouble themselves unduly about the material welfare of slaves like these. 58 Those who suffered the accident of sickness might, through no choice of their own, suddenly find themselves on reduced amounts of food, and the slave of a woman whose husband had provided the slave's clothing might well be required to hand it back, still in pristine condition, if the husband and wife divorced. 59

Some slaves were paid for their work as well. They could save this money to buy their own freedom, which might also be given as a reward for loyal service. There was a special freeing (manumission) ceremony, performed before a magistrate, where the owner struck the slave, who wore a tall felt cap. The blow represented the slave’s last indignity, and protection from being struck in future. Freed slaves (freedmen) were often set up in business by their former owners, becoming slave owners in their own right. 60 Slaves who had faithfully served their masters could expect to be freed at about the age of 30. Usually, however, this practice applied only to the slaves of urban households. Most agricultural slaves labored until they died. Upon gaining his freedom, a former slave adopted the name of his master. 61

The country slave had very little opportunity of gaining his freedom. He could run away, but he was sure to be caught, and when he was returned to his master he was cruelly flogged and the letter ‘P’ for Fugitives (Runaway) was branded on his forehead. For the town slave there was more hope that he might be set free. Sometimes his master would give him his freedom as a reward for long and faithful service, or he might buy it out of his savings, for it was possible for a town slave to earn and save money. 62

Citizenship

In the Republic, all free men and women born of Roman families were technically citizens (cives), although at first only men who could afford to own weapons—that is, those eligible for military service—could attend meetings of the citizen assemblies or hold public office. Because women were never accorded such political rights, they were always dealt as second-class citizens. Foreigners living in Roman territory were not citizens, and of course neither were slaves. So, Rome's body of active, fully privileged citizens was at first relatively small. Over the course of the centuries, however, that body steadily grew as citizenship and/or political rights were extended to various groups. For example, Rome frequently called on allies and other noncitizens to fight in the Roman army, and when these men completed military service, they received citizenship as a reward; moreover, because they acquired citizenship, they could legalize their marriages, which meant that their children were citizens, too. The state also periodically granted citizenship to individuals in return for various outstanding accomplishments or services, or for some other reasons. 63

The Family

The household (familia) consisted of a ‘nuclear’ family—the conjugal pair, their children and slaves— as well as their property. The father was the legal head of the family and had absolute control over all his children. His power extended to life and death—he had the right to expose newborn infants or to kill, disown or sell a child into slavery. Only at the father’s death did children become independent, although a son could be emancipated by his father. In law, free citizens were therefore either independent, or dependent on another. 64

Fathers were also responsible for their children’s education, and would teach their children basic reading and writing. Later, when the empire was established, most fathers sent their children to schools or hired tutors to teach them at home. Dionysus of Halicarnassus, a Greek historian wrote that the father’s role went back to the days of Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome. According to Dionysus, Romulus declared that the father had absolute power over his son. Whether he decided to imprison him, whip him or even kill him. Fathers also consulted with other adult family members when making important decisions. But fathers did expect obedience from their children throughout their lives. Roman families often included children from different parents. When a husband or wife died, the remaining spouse often remarried. 65

Men

The ancient Romans admired the characteristics that they believed allowed them to establish hegemony over their rivals. The hyper-masculine qualities of the Roman soldier became the hyper-masculine standard by which many Roman men measured their own manliness. Indeed, like many cultures that rose to prominence primarily through military aggression, images of the soldier’s life and the ideal manly life were often the same. Certainly many intellectuals in the Later Empire agreed with the time-honoured consensus that Roman pre-eminence had been achieved because its early citizens had avoided the life of effeminacy brought on by wealth and the sedentary life and fought in fierce wars which allowed them to overcome all obstacles by their manliness.

To be seen as real men, even the most affluent members of the aristocracy needed to prove their virility in the battlefield. Provincial governors until the third century C.E. were typically men from the aristocracy who functioned as both civilian administrators and garrison commanders. It is no coincidence then that in this era a Roman man’s identity remained tightly entwined with the notion that precarious manhood was best demonstrated and won on the battlefield.

From at least the first century A.D.., public displays of martial courage as a primary means of attaining a masculine identity had been complemented by alternative strategies of manliness based on non-martial pursuits. During the early years of the Principate, Stoic and Christian intellectuals had popularised codes of masculinity centred on self-control and a mastery over one’s passions such as anger and lust. To be seen as a true man, one did not necessarily need to prove his courage and manliness in times of war, but could earn a masculine identity through private and public displays of self-control, endurance, and courage by fighting internalised battles with his body and emotions. Public speaking and face-to-face verbal confrontations with political rivals provided an alternative means for privileged Roman men to display their verbal dexterity, as well as their manliness. As Gleason puts it, ‘Rhetoric was callisthenics of manhood.’ 66 During these often tense verbal confrontations, a man would be constantly judged not just by his mastery of words, but also on his ability to use the correct manly voice, keep hold of his emotions, and thus maintain the proper facial expressions and gestures. By concentrating notions of heroic masculinity into the figure of the emperor, imperial ideology created a portrait of the ideal emperor as a model of true manliness for all aspiring men to emulate. 67

Workmen and shopkeepers, schoolboys and men of letters were nearly always at work before the sun was up, seeing to do their business by the light of a smoky candle. The Roman gentleman, having risen, expected all the members of his familia to salute him and then he offered the daily prayers and made the offerings to the Lares and Penates. After his breakfast, when it was still barely light, the average Roman attended to some of his business.

At the Afternoon, the Roman returned home, where he had his midday meal. In the evening, between the siesta and the hour of dinner, which in ordinary times was usually about the ninth hour, the Roman took his exercise, in the Baths and in the Gymnasium. The younger men would go to the Tiber and the Campus Martius, and for the older men there were opportunities for all kinds of exercise in the halls adjoining the Thermae. The business of the day was over, and he devoted the remaining hours to his family or to the entertainment of his friends. 68 Whenever they felt like it, Roman men had sexual relations with their wives for reproduction and with slaves (male/female) for recreation. Courtesans provided recreation, companionship and sometimes advice. 69 Many Roman males had the somewhat hypocritical stance that their female relations should be honorable and chaste guardians of morality while at the same time they were more than willing to avail themselves of the services of lovers and prostitutes. 70

Women

Women, according to the opinion of the early Romans, were always children. They required protection and guidance during their whole life, and could never be freed from despotic control. Accordingly, when a Roman girl married, she had to choose whether she would remain under the control of her father, or pass into the control or—as it was called — into the hands of her husband. It is likely that in the early ages of the city she always passed from the power of her father into the hands of her husband. She thus became entirely subject to him, and was at his mercy. 71

Roman men did not consider women their equals, but they did not limit a woman to the inner chambers of her home. 72 If they were poor they attended to the work of the household. If they were rich and had a large household staff to relieve them of domestic cares, they had nothing to do but go out when the fancy took them, pay visits to their women friends, take a walk, attend public spectacles, or later go out to dinner. 73

Roman women were forbidden to serve in the army or to hold public office, although many wives of Magistrates and even emperors exerted influence on their husbands. 74 Loyalty and devotion to one's husband were also very important values attached to the idea of pudicitia. 75

The finest quality that a Roman woman could possess was pudicitia. For an unmarried girl, pudicitia meant sexual purity. For a wife, it meant faithfulness and devotion to her husband. Romans cherished stories of women who exhibited this quality. Romans gave their highest praise to women who had only one husband in their lifetimes. However, few women could win that praise in a society where girls married young, husbands often died while their wives were still young, and divorce was common and easy to obtain. The Romans prized obedience in a woman. Even a woman who was sharp-tongued and unruly at home was supposed to be quiet and obedient to her husband in public. They claimed that women were naturally weaker than men and that this weakness made them more likely to give way to greed, sexual desire, or jealousy. Whenever men relaxed their control over women, they believed, the women exploded into unseemly behavior—such as meddling in the business of men. In general, the Romans expected women to devote themselves to domestic matters. A woman's highest reward was the praise she would receive after her death for having lived up to her family's expectations. 76

Under the law of the early republic, a woman could not engage in business or own property independently of her husband, father, or guardian. These limits gradually loosened, however. By the time Rome had become an empire, the law still reflected the belief that adult women needed male guardians, but people generally ignored this rule. 77 Women had no legal rights over children. At her death she was expected to leave her property in her will to her children. If she died intestate, her property could pass to her father or other relatives. 78

Marriage

In Roman law, marriage was a status created by a simple private agreement. 79 The head of a traditional Roman family was the oldest male, called the paterfamilias (father of the family). He chose husbands and wives for his sons and daughters, arranging their marriages with another paterfamilias. Adult sons became head of their own families only when the paterfamilias died. Daughters often remained under their father’s authority, even after they married. 80 Marriage was equally unlawful, in the absence of the paternal consent, but these marriages were nevertheless indissoluble. 81 Hence A large proportion of the Roman men of the upper class regarded marriage as a burden and a vexatious interference with their liberty. 82

A marriage of the full and regular type could only be contracted between free citizens. There were varying degrees of the morganatic about all others, such as marriage with a foreigner or an emancipated slave. A non-Roman wife meant that the children were non-Roman. A man of the senatorial order could not marry a freed woman, if he wished to have the union recognized. Also no complete marriage could be contracted with a labouring under a degradation which was publicly inflicted by the authorities or by certain occupations. For this reason the actress on the ‘variety’ stage could not aspire to become even an acknowledged Roman wife, much less a member of the order which more or less coresponded to peerage. Nor could a Roman marry a relative within certain prohibited degrees. He was not infact allowed to marry any woman whom he already possessed what was called ‘the right to kiss’. 83

Marriage in ancient Rome could be characterized as successive polygamy (without any limit) and was one of many familial relationships that united kin to the head of the family. 84 Roman women tended to marry in their middle to late teens—earlier if they were from the upper class—while men married in their late twenties—again, earlier if they were of the nobility. The legal age of marriage for girls was 12, but a betrothal (sponsalia) could happen very early on, even when the couples were infants, although Augustus limited the length of a betrothal to two years. Consent of the parties involved (including the father) for a marriage to occur. For the girl, this consisted merely of not protesting her father’s (or her mother’s and father’s) choice of husband; although a woman’s consent was formally required, her feelings were not consulted and her opinion was never given any value in general.

For the upper classes, a digna condicio—a suitable match—was the aim; an unequal match would bring disgrace upon the better born partner. Roman marriage had little basis in romantic love or in sexual attraction; rather marriage and the procreation of children were seen as social duties. First, marriages between upper-class families at least were usually arranged, and romantic love was therefore a negligible factor, although it should not be discounted altogether, as there was the very real possibility of matrimonial devotion after marriage.

Few religious ceremonies were also accompanied the marriage. 85 Marriages with a more elaborate and costly ceremony, were complete with a priest and marriage contract. First, an animal would be sacrificed and its entrails read to see if the gods approved. For the wedding, June was always a popular month, took place in the atrium of the bride’s home. She typically wore a tunic-style dress (tunica recta) which was usually yellow. After a ring was placed on the third finger of her left hand and the matron of honor joined the couple’s hands, a contract was signed. Next, a procession was led to the groom’s home where festivities would last for several days. The bride was even carried over the threshold. Of course, the groom paid for the reception - complete with food, dancing and songs. 86

The young girl was carried to the house of her husband. Sometimes the husband himself took her. 87 After the marriage, a wife passed into the power of the husband; her legal position was the same as that of his daughter. At one time, the husband even possessed the right of putting her to death. 88

Many Romans felt a strong social obligation to provide a dowry (dos) for the bride when she wed. This is in part because, without a dowry (that is, money or property given to the groom by the bride’s family), the union could appear to be one of concubinage which was the severe resentment of the society. Dowry took the form of any number of different things (money, property, slaves); but generally it was a sum of money that the wife brought with her to the marriage to help support the household—the property of her father (dos profecticia) or other party/relative (dos adventicia)—sometimes payable in installments. In the event of the dissolution of the marriage it would have to be returned to the wife or to her family. The husband was legally entitled to keep part of the dowry (a retentio) under certain circumstances such as the wife’s sexual misbehavior, or if there were children of the union. 89 However, some cases are recorded in history which show that sometimes the men lent their wives to others. They used to do this so that their friends could also fulfill their sexual desires and could bear them children, but still they didn’t feel any shame while doing this. When the men did this, they rarely asked for the consent of their wives, and even if the wives refused to participate in these heinous acts, they would be forced to do so. Nussbaum states:

‘Cato had married Martia the daughter of Philippus as a girl; he was extremelyfond of her, and she had borne him children. Nevertheless, he gaveher to Hortensius, one of his friends, who desired to have children, but wasmarried to a childless wife, until she bore a child to him also, after whichCato took her back to his own house as though he had merely lent her.’ 90

Divorce

In the early empire divorce was easy 91 but women were reluctant to divorce because children of the marriage remained legally in the custody of their father. 92 Divorce was a fact of life for upper-class Romans 93 and the first Roman divorce is said to have occurred about the year 231 B.C., when Spurius Carvilius dismissed his wife because she bore him no children.

In those days, when the woman was still under the control of the husband, the woman could not divorce her husband, though her husband could divorce her without assigning a reason to her. In Augustus’s time, these laws were changed and his law required that the divorce would take place in regular form. The freedman of the man who wished to divorce would hand over the repudium, or bill of divorce, in the presence of seven Romans of full age, and the wife who wished a divorce did the same. The law ordained that a woman who was found guilty of adultery would be banished to an island, and would lose half of her dowry and a third of her property, and similar punishments were inflicted on a faithless husband. In the case of the wife, it still lay with the husband to inflict the penalty, and he himself was liable to be punished if he did not carry out the sentence. The husband could still kill his wife if he found her in the act; but he could execute vengeance only if he put to death both the guilty parties. 94

Remarriage

Remarriage was fairly frequent. Many men remarried without difficulty after divorce, although it was more difficult for a divorced woman to remarry, because men probably preferred younger women. For widows, remarriage was fairly normal and was required by the Augustan legislation. Among the upper classes, marriages, divorces and remarriages were often politically expedient. 95

Infidelity

In marriages men were held to vastly different standards than women. It was a long-standing cultural belief that men did not have to stay faithful in a marriage, whereas women did. However, there were limits; for instance, men were only allowed to have extra marital relations with someone who was a lower class than themselves – male or female. During the late Republic and early Empire upper-class men began to look to seducing the wives of their peers as a kind of sport and entertainment. Thus, even the women began to have sex outside their marriage. Famously, Julia, the daughter of Emperor Augustus, was completely unfaithful in her marriages. Part of Augustus’ family related legislation made his daughter’s and his own actions illegal.

Although, Augustus put on an appearance of a moral high-ground in public, which resonated with the populace of Rome, his private behavior was exactly what his laws aimed to avoid. Suetonius even claims that his wife was involved in his elicit affairs, she would find virgins and present them for Augustus to deflower. It seems Adultery became in inescapable vice for the upper echelons of Roman society. 96

Infanticide

Ancient Romans were pagans therefore, practicing infanticide was unproblematic. 97 The old Roman laws of the Twelve Tables stated that a child should be quickly killed, as the Twelve Tables ordain that a dreadfully deformed child shall be killed. 98 Any Roman who reached the age of marriage could look forward to burying one or more children, often very small ones. 99

The exposure of infants was widespread in many parts of the Roman Empire. This treatment was inflicted on large numbers of children whose physical viability and legitimacy were not in doubt. It was much the commonest, though not the only, way in which infants were killed, and in many, perhaps most, regions it was a familiar phenomenon. 100 A newborn was placed on the floor in front of the mother’s husband, if he picked the child up, it was considered his offspring, if not, the child was often killed. The Romans viewed this as a way of protecting the purity of their race 101 but they never thought that the one who committed this adultery was the real one who made this society impure. According to Philo’s explanation some even killed their babies with their own hands with monstrous cruelty and barbarity by throwing them in the depths of the sea after attaching some heavy substance to make them sink more quickly under its weight. 102 Still, some contemporary scholars never get tired in praising the uncivilized civilization of ancient Rome.

Food and Beverages

In ancient Roman society, food and drink were highly valued. Eating and drinking at banquets, feasts, and festivals were, at least for the wealthy, a major focus of social life. 103 Eating and drinking were used for a great variety of purposes, ranging from moral metaphors to character description or, more often, for character assassination, having little in the way of trustworthy objectivity. Perusing uncritically some of the rich and vivid remnants of ancient literature, a consensus has long held that the Romans went with hardly a pause from being frugal, upright vegetarians – ‘pulse-eaters’ – into decadence and unimaginable gluttony, eating and regurgitating the most diverse products of the known world all mixed together and moistened with rotten fish-sauce. 104 The diet of the vast majority of the population was extremely bland and dull. The ancient world was without such staples as coffee, tea, chocolate, potatoes, and tomatoes. Of the two grain crops most widely produced nowadays, rice and corn, the former was known but little grown, the latter completely unknown. 105

Diet and dining customs depended on the standard of living and geographical region. The diet of the most people was frugal, based on corn (grain) for bread or porridge, olive oil and wine, and in addition pulses, vegetables and various fruits and nuts were eaten, depending on the geographical location. Cereals, mainly wheat, provided the staple food. Originally husked wheat (far) was prepared as porridge (puls), but later on species of wheat (eventually known as frumentum) were cultivated and made into bread. Bread was sometimes flavored with other foods such as honey or cheese. It was eaten at most meals, accompanied by products such as sausage, domestic fowl, game, eggs, cheese, fish and shellfish. Fish and oysters were particularly popular with those who could afford the cost. Meat, especially pork, was eaten, but did not play an important role in the diet, because it was expensive, as was fish. Meat was more commonly eaten from the 3rd century due to improved husbandry. 106

Other foods, such as vegetables, fruits, and spices, mainly provided variety to the diet. Rich in protein, legumes were added to bread as well as eaten with vegetables or other foods. Despite their nutritional value and their versatility, beans and peas were considered the poor man's food. Legumes were also fed to cattle. During the reign of the Roman emperor Caligula, legumes were even used as packing material in shipping large monuments overseas. Grain was ground into flour, which was then used to make many varieties of Bread, porridge, and other foods. Biscuits and cakes were prepared by adding honey, fruit, eggs, or cheese to the flour. In Rome, bread production became a major industry. However, even the best breads available at the time were coarse. 107 Bread, cakes and pastries were produced commercially and at home. Circular domed ovens were used mainly for baking unleavened bread and pastries—a fire was lit inside the oven and was raked out before the food was put in. Most food was cooked over a brazier or open hearth, with cauldrons suspended from a chain or cooking vessels such as frying pans set on iron gridirons or trivets over a fire of charcoal. Cooking was done in the kitchen, and smoke from fires escaped through the roof or a vent in the wall. There were no chimneys, and so the atmosphere in the kitchen could have been very unpleasant, and the work very hard, involving squatting in front of ovens and the lifting of heavy amphorae and water containers. Cooking was also done outside. Many people, particularly tenement dwellers, probably had no cooking facilities, although communal ovens may have been available. The wealthy had slaves to do their cooking. Food was often cooked with fruit, honey and vinegar, to give a sweet-and-sour flavor. 108

The Romans ate numerous species of birds, including swans, ducks, owls, pigeons, and nightingales, as well as their eggs. Many species of Fish and Shellfish were eaten, including tuna, mackerel, sturgeon, mussels, and oysters. Fresh fish were fried, grilled, baked, broiled, or added to sauces. Fish were also preserved by salting, drying, or pickling. The internal organs of fish were fermented to make the famous Roman fish sauce Garum. 109

Meat was considered a luxury, and that only the wealthy could afford it. This view is often elaborated further with claims that only pigs were bred for consumption by the rich and that cattle were only slaughtered when old and could no longer be of any service, that sheep and goats were kept for wool, milk, and cheese, and that fish was a luxury food. 110 The poor rarely ate meat. A family entitled to a meat dole might receive five pounds of pork each month for five months of the year.

Augustus’s advisor Maecenas made donkey meat a fashionable delicacy. Pliny also records that the hard skin of an elephant’s trunk was sought after by gourmets, not because it was actually thought to taste good, but because eating the trunk was as close as they could come to chewing on the vastly expensive but quite inedible ivory of the tusks. Although horse meat was much appreciated in many parts of Europe, the Romans never ate it except in dire circumstances. 111 Contemporary research has proved that human beings adopt some of the power and traits of the animal which they consume. Since the ancient Romans consumed animals such as pigs and donkeys, their habits also became similar to them. Resultantly, they became more animalistic and inhumane in their lifestyles.

Everyone consumed cultivated fruits, such as apples, pears, dates, and figs, as well as several different species of wild fruits. Berries were rarely eaten, however, and tomatoes, bananas, and most citrus fruits were not available. Fruits were eaten raw, dried, preserved, and cooked, and such fruits as dates and figs were used to sweeten other foods and to help ferment grapes in the production of wine.

Wine was drunk most commonly, generally watered down (apparently to curb drunkenness), as well as spiced and heated. Drinking undiluted wine was considered barbaric. Wine concentrate (must) diluted with water was also drunk. Posca was a particularly common drink among the poorer classes, made by watering down acetum, a low-quality wine very similar to vinegar. Bronze hot water heaters or samovars with taps and space for charcoal were luxury items for use in banquets, possibly for heating water to mix with wine. Beer (fermented barley) and mead (fermented honey) were drunk mainly in the Northern provinces. Milk, usually from sheep or goats, was regarded as an uncivilized drink, and was reserved for making cheese and for medicinal purposes. A good water supply was often supplied to towns and even individual houses or villas of the wealthy, but it is uncertain to what degree water was chosen to be drunk rather than used for cooking, laundry, cleaning and bathing. 112 Occasionally, wine was consumed before a meal, but most often it was drunk after the meal was finished. Everyone, including young children, regularly consumed wine. The large variety of wine jugs, bowls, cups, and glasses produced also indicates how significant wine was for the people of the time.

Meals of the Day

The Roman dinner consisted of three courses. First, there was an appetizer—often an egg, seafood, or snail dish, or perhaps pumpkins, asparagus, or other vegetables. The main course, which followed, consisted of meat or poultry. Finally, there was a dessert of fruit or other sweet food. Wine always followed the meal. Although poor people generally had a less varied and exotic diet, they usually had access to grain, since free grain was frequently distributed to the poor during shortages. 113 The Romans generally ate one main meal a day. Breakfast (ientaculum) was not always taken, but was in any case a very light meal, often just a piece of bread. Breakfast originally appears to have been followed by a main meal of dinner (cena) at midday and by supper (vesperna) in the evening. However, dinner came to be taken later in the day, eventually becoming the evening meal. Supper was then omitted and a light lunch (prandium) was introduced between breakfast and dinner, so that the Romans came to eat two light meals in the day and a main meal (cena) around sunset. For the poor, most meals consisted of cereal in the form of porridge or bread, supplemented by meat and vegetables if available. For the reasonably wealthy, the main meal consisted of three courses, ab ovo usque ad mala (from the egg to the apples). The first (gustatio or promulsis) was an appetizer, usually eggs, raw vegetables, fish or shellfish, prepared in a simple manner. The main course (prima mensa) consisted of cooked vegetables and meats—the type and quantity of such dishes depended on what the family could afford. This was followed by a sweet course (secunda mensa) of fruit or sweet pastries.

The Romans often sat upright to eat their meals, but the wealthy reclined on couches, particularly at dinner parties, and often dined outdoors in their private gardens when the weather was fine. Slaves and the poor squatted or crouched while eating. A variety of cooking vessels was used, largely in coarse pottery and bronze. In Northern provinces there is evidence for tables used with upright chairs. For the poorer classes, tableware probably consisted of coarse pottery, but there was also available a range of vessels in fine pottery, glass, bronze, silver, gold and pewter. Food was cut up beforehand and eaten with the fingers. Knives had iron blades and handles of bone, antler, wood or bronze. Bronze, silver and bone spoons are also known, for eating liquids and eggs, and their pointed handles were used for extricating shellfish or snails from their shells. 114

Foods were categorized according to their nature as heating or cooling, moistening or drying. At the same time they were either strong, medium, or weak. Strong foods were believed to be most nourishing but hard to digest, weak foods least nourishing but easy to digest.

Among the strong foods, generally counted, were beef and the meat of other large domesticated quadrupeds; all large game such as the wild goat, deer, wild boar, wild ass; all large birds, such as the goose, peacock, and the crane; all sea monsters, such as the whale and the like; all pulses and bread-stuffs made of grain, honey, and cheese. Among foods belonging to the class of medium strength were counted: the hare, birds of all kinds from the smallest up to the flamingo, fish, and root and bulb vegetables. Finally, to the weakest class were thought to belong snails and shellfish, all vegetable stalks, gourds, cucumbers and capers, olives, and all orchard fruits. Strong foods were heating foods; in addition to being most nutritious they were also thought to be aphrodisiacs. The more heating the food, the more it was supposed to increase sexual potency, or at least sexual appetite 115 and such foods were adored by the Romans because it increased their sexual pleasure.

Roman Buildings

The Romans recognized two basic kinds of houses, the elite aristocratic houses, which they called domus (mansions or town houses), and apartments for the rest of the urban population, called insulae (residential units). 116

The private houses of the Romans were poor affairs until after the conquest of the East, when money began to pour into the city. Many houses of immense size were then erected, adorned with columns, paintings, statues, and costly works of art. Some of these houses are said to have cost as much as two million dollars. The principal parts of a Roman house were the Vestibulum, Ostium, Atrium, Alae, Tablinum, Fauces, and Peristylium. The Vestibulum was a court surrounded by the house on three sides, and open on the fourth to the street. The Ostium corresponded in general to our front hall. From it a door opened into the Atrium, which was a large room with an opening in the centre of its roof, through which the rain-water was carried into a cistern placed in the floor under the opening. To the right and left of the Atrium were side rooms called the Alae, and the Tablinum was a balcony attached to it. The passages from the Atrium to the interior of the house were called Fauces. The Peristylium, towards which these passages ran, was an open court surrounded by columns, decorated with flowers and shrubs. It was somewhat larger than the Atrium. 117

The elite houses in the city, the domus, had a layout including courtyards and receptions rooms, patterned after the rural estate of the Romans, the villa. Domus can be thought of as urban villae. These houses were usually called ‘atrium-peristyle’ houses because they have both of these architectural features – basically forms of open courtyards – the first being an Italian feature, the latter an import from the Greek east. These were clearly the most ubiquitous form of elite housing in Rome. 118 Early town houses were usually built around an atrium, an unroofed or partially roofed area. They were later roofed except for an opening (compluvium) in the roof to provide light and air. From the late 2nd century B.C. this type of house had extra rooms, a peristyle courtyard and/or garden (a courtyard or garden surrounded by a portico), and sometimes baths. Such a house only had one doorway and one or two windows opening onto the street, which presumably increased security and reduced noise and other nuisances. The atrium was a reception hall and living room. 119 Behind the atrium was the tablinum, the head of the house’s study, which would often look out onto the garden. Here the owner received clients, less-wealthy Romans who came to ask him for favours. In return for legal or financial help, clients gave their patrons political and social support. Important family documents were kept in a chest in the tablinum. The triclinium, or dining room, was named after the three sloping couches where the diners reclined to eat. The platform was spread with comfortable cushions. Some houses had an outdoor triclinium, where the family could enjoy eating out on summer days, as well as a main dining area indoors. 120 The kitchen and bathing room were located to the right of the entrance. Bedrooms were often arranged in a row on the ground floor of the town house, while rooms for servants, smaller and darker than other rooms, were located near the kitchen and work areas. 121 The kitchens in Pompeii were small and plain, for they would be seen only by the slaves who worked there. There was usually a raised brick oven, on top of which charcoal was burned. Kitchens were equipped with a wide range of utensils, including strainers which would have been used for straining wine or sauces. Food supplies were stored in pots called amphorae, some of which would be buried in the ground to keep them cool. Every house had a miniature shrine, called a lararium, where offerings were made to the gods who watched over the family and the home. This shrine was made to resemble a small temple, with a painting of the goddess Minerva on the wall. Bronze statues of the household gods stood on the shelf. 122

The vast majority of the population of Rome lived in apartment buildings of several stories (insulae , literally islands; hence the Italian isolato, meaning a block on a street). Insulae were notoriously dingy, cramped, and vulnerable to outbreaks of fire. A 4th-century A.D. catalog of the regions of the city records 46,602 insulae , but only 1,797 freestanding homes (domus). 123 The term insulae (rectangular areas of building plots within a town) was also used for rectangular apartment blocks. This did not imply that they were so large as to cover a whole insula: There were six to eight apartment blocks within an insula. They were built around an open courtyard with a shared staircase and usually had shops fronting the street at ground level. There were often three or more stories, making the courtyard more of a light well in the center of the building. Ground-floor apartments were more desirable, as upper floors had scarce water and cooking facilities. 124

Shops were ubiquitous in Rome, Pompeii, Herculaneum and Ostia, where four basic types are recognized: shop alone, shop with backroom; shop with mezzanine apartment; and shop with both backroom and mezzanine apartment. These four types cover the vast majority of possibilities. Shops were adjacent to private houses, in single rows, back-to-back, in every possible combination around courtyards, with and without colonnades, arcades and porticos, backing onto corridors and alleys, with and without backroom, with olive or wine presses with basins; there are even shops with their own pavements in front of them, and shops arranged as purely shopping bazaars. 125

Lower-class Romans often lived in the back of their shops or in tenement houses of cramped, subdivided rooms. Tenement houses were often hastily built of the cheapest materials, with walls of timber, reeds, and stucco. These dwellings provided little privacy, especially on the upper floors, which consisted of a single large room that served as both a living and sleeping area. There were no kitchens. Cooking was done over a brazier. Water had to be drawn from public fountains and carried upstairs for domestic use. Human waste was collected in chamber pots and emptied into drainpipes. Public latrines were available, as well as public baths located throughout the city. For poor Romans, an alternative to a tenement house was a ground-floor apartment without a second story, or an apartment above a commercial establishment. Because of the closeness of so many apartments and the widespread use of oil lamps and braziers for lighting, heating, and cooking, Roman cities were always at risk for fire. A fire in Rome in A.D. 64 destroyed many districts of the city and resulted in strict new building regulations. Communal walls were outlawed, and residents were required to ensure that water was available for emergencies. Dangerous as it might be, the tenement style of housing used by the Romans survived into the modern age. 126

Towns might have one or several public latrines (foricae), often associated with the public baths. They consisted of a sewer over which a line of seats of wood or stone were set. The seating was communal, with no partitions. The sewer was flushed with waste water, usually from the baths, and in front of the seats was a gutter with continuous running water for washing. The same system was used in latrines in forts and fortresses. Few private houses had latrines connected to sewers, and most used commodes or chamber pots. It is uncertain if the waste was deposited in the street or in public sewers, or else was collected for manure for gardens. 127

Houses were commonly built of stone, but in the provinces, timber frames with walls of wattle and daub infill were often used, set on foundations or low walls of stone. In some areas houses were built of mud brick. Materials used for decoration are a more reliable indicator of wealth, as many were imported from a distance at great cost. Surviving evidence, such as at Pompeii, shows that the interior of most houses was decorated and that the street frontages of buildings were painted in red on the lower part of the walls and white above. 128

The floors were covered with stone, marble, or mosaics. The walls were lined with marble slabs, or frescoed, while the ceilings were either bare, exposing the beams, or, in the finer houses, covered with ivory. The main rooms were lighted from above; the side rooms received their light from these, and not through windows looking into the street. The windows of rooms in upper stories were not supplied with glass until the time of the Empire. They were merely openings in the wall, covered with lattice-work. To heat a room, portable stoves were generally used, in which charcoal was burned. There were no chimneys, and the smoke passed out through the windows or the openings in the roofs. The rooms of the wealthy were furnished with great splendor. The walls were frescoed with scenes from Greek mythology, landscapes, etc. In the vestibules were fine sculptures, costly marble walls, and doors ornamented with gold, silver, and rare shells. There were expensive rugs from the East, and, in fact, everything that could be obtained likely to add to the attractiveness of the room. Candles were used in early times, but later the wealthy used lamps, which were made of terracotta or bronze. They were mostly oval, flat on the top, often with figures in relief. In them were one or more round holes to admit the wick. They either rested on tables, or were suspended by chains from the ceiling. 129 The atrium was often open to the sky and rain fell through a skylight into an impluvium, a basin in the center of this space. The water was stored for future use in an underground tank. 130

Attire

Knowledge about ancient clothing comes from three sources: the remains of garments, literary works that mention clothing, and images of clothing in sculpture and painting. No garments have survived whole from ancient times, but scraps of fabric found in tombs show how the Greeks and Romans made their textiles. 131 The Romans were very sensitive to distinctions of dress and the symbolic associations of costume. 132

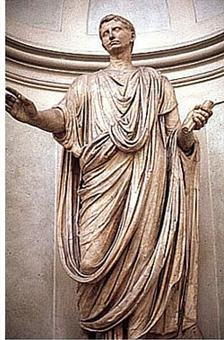

Men

The Roman men usually wore two garments, the tunica and toga. The former was a short woollen under garment with short sleeves. To have a long tunic with long sleeves was considered a mark of effeminacy. The tunic was girded round the waist with a belt. The toga was peculiarly a Roman garment, and none but citizens were allowed to wear it. It was also the garment of peace, in distinction from the Sagum, which was worn by soldiers. 133

The toga was made of a single piece of cloth. It was not a rectangle, but had one rounded or curved side. The toga was worn like the himation, draped over one shoulder and loosely fastened at the waist or hip. The curved side was worn at the bottom. Ordinary citizens usually wore plain, white togas. Some Romans wore togas that had a decorated border, the width and color of which were determined by the wearer's age and social class. Certain colors and patterns were reserved for the highest-ranking officials. For example, from the time of Augustus only the emperor could wear a purple toga. This is why becoming emperor is sometimes referred to as ‘taking the purple.’ Children of both sexes wore togas, but among adults, the toga was a man's garment. 134 Toward the end of the republic, it became more complex with a sinus and umbo. The sinus consisted of the drapes that fell from the left shoulder to the right thigh as a pocket and could be brought up over the right shoulder, forming a sling. The umbo was a projecting mass of folds in front of the body that could be pulled up to form a hood. A Roman with the toga drawn over his head is represented as a priest. A diagonal band of cloth from the shoulder to the armpit was known as a balteusor belt. Togas for senators had a broad purple stripe (latus clavus);for equestrians a narrow purple stripe (angustus clavus); emperors’ togas were entirely purple. A toga candida (white toga) was worn by candidates for office, the togas made whiter by being rubbed with chalk. A toga pulla was of natural black wool and was worn at funerals. In the late Roman period, those of senatorial rank wore a shorter, less voluminous toga, no longer with a balteusand umbo, but a more simple triangular fold of material. It was worn over a thin long-sleeved tunic and beneath that a longer under tunic. By the 4th century the toga went out of fashion as a ceremonial garment. 135 The toga had to be worn on all ceremonious occasions: when the Roman married, when he performed his duties as magistrate or governor, and by the general when he entered Rome in triumph. When a Roman died, his body lay in state in the atrium of his house, and there he lay wrapped for the last time in his toga. Only a free Roman citizen might wear the toga, and were he sent out from Rome into exile, he was obliged to leave it behind him. The toga was the outward symbol of Roman citizenship. 136

Tunics worn by charioteers were dyed the color of their faction. A dalmatic (dalmatica) was originally a short-sleeved or sleeveless tunic, but by the late empire it had long sleeves. It was made of various materials, such as wool, linen and silk, and was worn by people in high position. It was adopted as an ecclesiastical garment. 137 The wearer slipped the tunic on over his or her head and fastened it with a belt, often pulling it up to hang in a loose fold over the belt. The most traditional and important outer garment was the toga. During most of Roman history, a male Roman citizen who did not wear a toga ran the risk of being mistaken for a workman or a slave. 138

Women

Women of early Rome also wore togas, but later only prostitutes and other women considered of ill repute (such as adulteresses) were obliged to wear them. Women then wore tunics. Married women (matrons) wore a tunic covered by a stola, a long, full dress gathered up by a high girdle, with a colored border around the neck. It became a symbol of the Roman matron and could be worn by patrician women and by freedwomen married to citizens. An adulteress could not wear a stola as she was no longer a respectable matron. Women also wore cloaks (pallae) when they went out, in order to hide their head. They did not have hoods but were rectangular mantles drawn up over the head. A widow did not wear a palla, but a ricinium, a type of shawl, probably dark in color. The clothes of the wealthy were in various colors and fine materials, such as muslins and silks. In some areas women also wore close-fitting bonnets and hairnets. 139 Married women were expected to cover their heads in public. 140 The ladies indulged their fancy for ornaments as freely as their purses would allow. Foot-gear was mostly of two kinds, the Calceus and the Soleae. The former was much like our shoe, and was worn in the street. The latter were sandals, strapped to the bare foot, and worn in the house. The poor used wooden shoes. 141

Shoes

Many Romans probably went barefoot. For those who were shod, various types of leather shoes and boots were worn, varying from heavy hobnailed sandals and enclosed shoes to light sandals and slippers. A carbatina was a sandal made from one piece of leather, with a soft sole and an openwork upper fastened by a lace. A soccus had a sole without hobnails and a separate leather upper. A calceus was a hobnailed shoe secured by laces. A solea was a simple sandal with a thong between the toes and a sole with hobnails. A caliga,worn by soldiers, was a heavy sandal with a hobnailed sole and a separate leather upper, fastened by thongs. Some caligae were stamped with the maker’s name. Wooden clogs and sandals are also known, and footwear of felt, cork and plant fibers was probably made. 142

Accessories

Roman men and women wore the subligaculum, a linen undergarment similar to the Greek perizoma. Women might also wear a strophium, or brassiere. Made of linen or leather, the strophium was a band that supported and wrapped the breasts. 143 Short leather trousers were worn by soldiers, in particular cavalrymen, but long woolen trousers (braca) were mainly worn by barbarians outside the boundaries of the empire. Most men’s legs were bare or wrapped in leggings. Capes and cloaks of various styles and sizes are also known, of thick wool or leather, some with hoods. Hats were rarely worn. In the empire the Romans spent much time in bathing and massaging. Toilet instruments are common finds, singly or in sets, and were usually made of bronze. They include nail cleaners, tweezers, toothpicks and earpicks. Razors were of bronze or iron, and combs were of bone or wood. Strigils made of bronze and sometimes iron were used to scrape oil, sweat and dead skin from the body after bathing. Ligulae were used for extracting cosmetics or medicines from narrow unguent bottles. Mirrors were of polished bronze and silver, and occasionally of silvered glass. 144

Social Gatterings

Public entertainment in particular played an important part of life in Rome and to a large extent in the provinces as well. Juvenal remarked that the city mob in Rome was only interested in panem et circenses (bread and circuses). Although this was a satirical exaggeration, but it demonstrated the important place of entertainment in their everyday lives. 145 The huge open spaces of the Roman Forum and the nearby Imperial Fora were frequently used to stage cash hand-outs, public banquets, and (before permanent amphitheaters became available) gladiatorial games and beast hunts. The fora would also regularly host market days and, it must be imagined, hucksters, snake-oil salesmen, performers, reciters, sidewalk orators, and traveling troupes of entertainers were a constant feature of these piazzas, as well as of other public spaces in the city. 146 The Romans had no Sundays or other days in the week on which every day business was regularly stopped, but their calendar provided for a number of holidays. These amounted to about a hundred days a year, and on some great and unusual occasions there were additional holidays announced. These days were given up to public amusements, to the theatre, the circus, and the spectacles in the amphitheater. The theatre did not appeal to the Romans as it did to the Greeks, and the Circus and the Amphitheatre are more characteristically Roman. All these public amusements were provided for the people by the state, but as they grew more elaborate and magnificent, the Emperor and private individuals used to help in providing them, and at the end of the Republic, the providing of public amusements had become a favourite method of trying to win popular favour. All through Roman history the Games of the Circus played a very important part in the life of the Roman people. Every year in September the Ludi Romani took place in the Circus Maximus. 147