Military System of Ancient Greece – Generals, Military & Navy

Published on: 15-Jun-2024(Cite: Khan, Dr. (Mufti) Imran & Hamdani, Mufti Shah Rafi Uddin. (2020), Military System of Ancient Greece, Encyclopedia of Muhammad  , Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 257-274.)

, Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 257-274.)

Greece was engaged in warfare from the Greek Dark Ages onwards. In the ancient Greek world, warfare was seen as a necessary evil of the human condition, although this theory is gravely flawed. Warfare in ancient Greece consisted of small frontier skirmishes between neighboring city-states, lengthy city-sieges, civil wars, or large-scale battles between multi-alliance blocks on land and sea, even though the vast rewards of war outweighed the costs in material and lives. Whilst there were long periods of peace and many examples of friendly alliances; the powerful motives of territorial expansion, war booty, revenge, honor, and the defense of liberty ensured that throughout the Archaic and Classical periods the Greeks were regularly engaged in warfare both at home and abroad. These continuous wars were responsible for killing hundreds of thousands of people and converting a similar if not greater number into slaves. Therefore, the military of the ancient Greeks were more concerned in expanding their territory with the use of force and terror rather than living peacefully with other people.

The earliest evidence for Greek warfare comes from Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. These epic poems were probably composed in the 8th century B.C., but they reflected a much earlier Mycenaean phase. As they are epic poems, they cannot be treated as reliable and accurate historical documents. However, a great deal of information can be extracted and combined with the available archaeological evidence for the Mycenaean period. 1

War and the use of land were the building blocks of Aristotle's Politics and Plato's Republic. Both utopias, which have not been materialized ever and will never be in future, assume that before man can speculate, contemplate, educate and argue, he must first figure out how to eat and how to fight. The soldier and the farmer may be forgotten or even despised in our own culture, but in the Greek mind agriculture and warfare were central to a workable society, in which both professions were to be controlled by a rational and egalitarian citizenry. There was not a major Greek figure of the fifth century - intellectual, literary, political - who did not either own a farm or fight. Very often he did both. While talking about war, the philosopher Heraclitus said that war was 'the father of all, the king of all'. 2

War was almost a permanent condition in the Classical era. The Greek states were only united in a common cause twice, when they combined their forces to defeat the Persians. The rest of the time, they competed endlessly for precedence amongst each other. When one became too powerful, others formed temporary alliances against it to cut it down to size. From 490 to 338 B.C., the city of Athens was at war for two out of every three years.

Paradoxically, this resulted not so much from mutual antipathy as from shared values. The Greeks, according to the modern classical scholar Hans van Wees, were united ‘not only by a common language and religion, but also by a common rivalry to be the best’. ‘Rivalry and conflict between city-states’, claims van Wees, was ‘largely inspired by the wish to defend and enhance the intangible honor of the community, more than anything else, the states in question sought to gain prestige by demonstrating their superiority over their neighbors’. 3

After the republican constitutions of the Greeks were established, their armies consisted chiefly of militia. Every citizen was obliged to serve in it, unless the state itself made particular exceptions. In Athens, the obligation continued from the eighteenth to the fifty-eighth year. Each citizen was therefore a soldier, even the resident strangers were not always spared. In times of distress even the slaves were armed with promise of freedom if they did their duty properly. 4

Notable Generals

Mitiades (550-489 B.C.):He was largely responsible for the Greek victory at Marathon; a fatal infection from a battle wound on Paros, ended his plans for early Athenian naval expansion in the Aegean.

Leonidas (540-480 B.C.):As a Spartan king, he led an allied Greek force to Thermopylae. His courage became mythical through his stubborn refusal to abandon the pass, and his desire instead to die with 299 of his royal guard still fighting.

Aristides (530-468 B.C.):He was nicknamed ‘the Just’, and proved to be an able Athenian statesman. Aristides shared command at the battles of Marathon, Salamis, and Plataea and helped to lay the foundations of the Athenian empire.

Aechylus (525-546 B.C.):He was the great Athenian tragedian, author of the Oresteia and some ninety other tragedies (seven alone survive), fought at marathon, where his brother was killed at the beach. His epitaph records only his military service.

Themistocles (524-459 B.C.):He was a gifted Athenian general and architect of Athenian naval supremacy, was also responsible for the creation of a 200-ship Athenian navy and its brilliant conduct at Salamis. His later years were characterized by political intrigue and condemnation by both Athens and Sparta.

Pericles (495-429 B.C.):A brilliant Athenian imperialist and statesman who for nearly oversaw the rise of Athenian economic, military and political power. He died at the beginning of the Peloponnesian war from the plague (a result of his own policy of forced evacuation of Attica within the confines of Athens.).

Brasidas (Died 422 B.C.):He was without question the most innovative commander in the history of the Spartan state. By using light-armed troops and freed helots to carve out Spartan bases and win allies, his efforts checked Athenian ambitions for much of the early Peloponnesian war, until his death at Amphipolis.

Cleon (Died 422 B.C.):He appears as a roguish demagogue in Thucydides’ history, but he was not always inept in the field, and won an impressive victory over the Spartans at Pylos (425 B.C.) before dying in the battle for Amphipolis.

Alcibiades (451-404 B.C):The flamboyant Athenian politician and general, at one time or another was in the service of Athens, Sparta and Persia. As architect of the disastrous Sicilian expedition, and advocate of the Spartan occupation of Decelea, he helped to ruin the power of fifth-century Athens.

Agesilaus (445-359 B.C.):As a Spartan king for nearly forty years, he campaigned in Asia, Egypt, and on the Greek mainland to extend Spartan hegemony - a mostly failed enterprise since the king had no real understanding of the role of finance, fleets or siege craft in a new era of war.

Aeneas Tacitus:An Arcadian general who wrote the earliest surviving Greek military treatise, a work on siege craft, which is the rich source of Greek stratagems to protect cities against attack.

Chabrias 5 (420-357 B.C.):He fought on behalf of Athens for over three decades as professional commander at various times against Persia, Sparta and Boeotia. He was adept at using light armed troops in concert with fortifications and as mobile marines.

Iphicrates (415-353 B.C.):He brought light armed peltasts (light infantry) to the fore of the Greek warfare of the fourth century. As an Athenian general, he destroyed a regiment of Spartan hoplites at Corinth and employed his military innovations in various campaigns on behalf of Athens.

Lysander (Died 395 B.C.):He was the Spartan general who commanded the Peloponnesian fleet in its final victories over Athens in the Peloponnesian war. His attempt to extend Spartan hegemony to Asia Minor and Boeotia was cut short by his death in battle at Haliartus.

Demosthenes (384-322 B.C.):He was an active Athenian general of the Peloponnesian war. His success at Pylos and Amphilochia were more than offset by crushing defeats in Aetolia, Boeotia, Megara and Sicily.

Phillip II (382-336 B.C.):He was the brilliant and ruthless architect of Macedonian hegemony who conquered Greece through political realism, tactical innovation and strategic brilliance. Had he not been assassinated; the Macedonian army might have been content with the conquest of western Persia.

Alexander the Great (356-323 B.C.):Through sheer military genius conquered the Persian Empire in little more than a decade. But Alexander's megalomania and desire for divine honors helped to pervert the legacy of Hellenism and left hundreds of thousands of Asians dead and displaced in his murderous wake. Ancient and modern ethical assessments of Alexander vary widely and depend entirely on the particular value one places on military prodigy and conquest. 6

Army

Most evidence on the organization of armies relates to Sparta, to a lesser extent to Athens, and to the later army of Macedonia. Very little is known about armies of other states, and most evidence is derived from non-contemporary authors. Before the 4th century B.C., there is only evidence that the Spartan troops were trained, possibly because the hoplites in other Greek states were of a high social standing, who would not have tolerated any training. 7

The Following was the composition of the Greek Army:

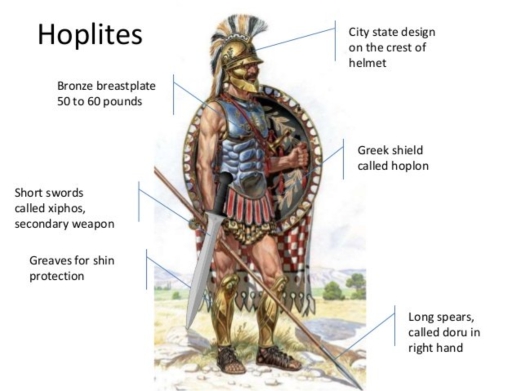

Hoplite

This term refers to the heavy infantryman of the Greek world, from about 700–300 B.C. The early hoplite was named for his innovative shield, the hoplon, which was round, wide (three feet in diameter), heavy (about 16 pounds), and deeply concave on the inside; it was made of wood reinforced with Bronze, often with a bronze facing. The soldier held the shield by passing his left forearm through a loop on the inside center and then gripping a handle at the far inside edge. This arrangement helped with the necessary task of keeping the shield rigidly away from the man’s chest. The shield was notoriously difficult to hold up for a long period of time; a hoplite fleeing from battle always threw away his cumbersome shield, and even victorious soldiers could lose their shields in the melee. In militaristic societies such as Sparta, keeping your shield meant keeping your honor, as indicated by the Spartan mother’s proverbial command to her son: “Return with your shield or upon it.”

The rest of the hoplite’s armor, or panoply, included a helmet—typically beaten from a single sheet of bronze and topped with a crest of bronze or horsehair—and a bronze breastplate and greaves (metal shin guards); under the breastplate the man would wear a cloth tunic. The offensive weapons were a six to eight-foot-long spear for thrusting (not throwing) and a sword of forged Iron, carried in a scabbard at the waist. By various modern estimates, the whole panoply weighed 50–70 pounds, and it seems that, on the march and up until the last moments before battle, much of a hoplite’s equipment was carried for him by a servant or slave. A hoplite did not normally fight alone; he was trained and equipped to stand, charge, and fight side by side with his comrades, in an orderly, multi-ranked formation. The hoplite relied foremost on his spear, thrusting overhand at the enemy while trying to shield himself from their spear-points. The sword was used if the spear was broken or lost. The armor’s weight, plus the need to keep in formation, meant that hoplites could not charge at full speed for any distance. Two hundred yards would seem to be the farthest those hoplites could actually run and still be in a condition to fight.

Yet this heavy armor did not make the hoplite invulnerable. It was not practical for armor to cover a man’s neck, groin, or thighs, and these were left exposed. References in ancient poetry and art make it clear that deadly wounds to the neck and groin were common, as were fatal blows to the head (possibly received from an inward denting of the helmet). Sometimes the bronze breastplate could be pierced—as demonstrated by evidence that includes the recently recovered remains of a Spartan hoplite, buried at a battle-site with the fatal, iron spear point lodged inside his chest.

Hoplites could fight effectively only on level ground; hilly terrain scattered their formation and left the individual soldiers open to attacks from lighter-armed skirmishers. Similarly, hoplites that broke ranks and became isolated—in retreat, for example—were easy prey for enemy cavalry.

On warships, hoplites served as “marines.” There they were armed mainly with javelins (for throwing) and were employed in grapple-and-board tactics. Soldiers unlucky enough to fall overboard would be dragged to the bottom by their heavy armor. Hoplite armies began their history as citizen armies. In most Greek cities, each man up through middle age who could afford the cost of a panoply was required to serve as a hoplite if his city went to war. (Alternatively, those rich enough to maintain horses might serve in the cavalry.) In states governed as oligarchies, a man had to be of hoplite status or better in order to be admitted as a citizen. 8

The Spartan army was commanded by the king and was divided into six regiments known as morae, each consisted of 576 men. Each mora was commanded by a polemarch and consisted of four lochoi. Each lochos (now 144 men) was the standard unit of the phalanx and was commanded by a lochagos. A lochos was divided into two pentekostyes. Each pentekostys (now 72 men) was commanded by a pentekonter and was divided into two enomotiai. The enomotia was the smallest unit of the army and was commanded by an enomotarch. The enomotia was composed of three files of 12 men or six half-files of six men. There were also rearguard officers called ouragoi, who could have been an integral part of the unit, forming the rear rank of each enomotia. In phalanx formation, the other officers would fight at the front of the right-hand file of the unit that they commanded.

The King’s Bodyguard (hippeis) served in the first mora. It consisted of 300 specially selected hoplites that were regarded as the best in the army. They were chosen by three hippagretae (hippagretai)—men chosen annually by the ephors specifically for selecting hoplites to serve in the hippeis. In addition, each mora had an attached unit of cavalry, also called a mora. These cavalry units, each about 60 strong, began to be used only near the end of the 5th century B.C., during the Peloponnesian War. When on the march, the Spartan army was led by the cavalry with the sciritae (skiritai) forming a screen in front of the column to provide advance warning. The sciritae were originally perioeci from the town of Scirus. They were foot soldiers serving as lightly armed scouts and outpost guards. 9

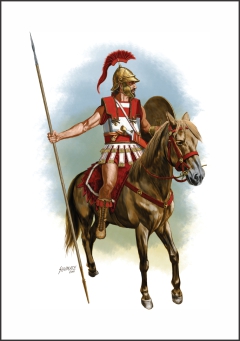

Cavalry

Cavalry, that is men fighting from horseback, may have played a role in late Mycenaean armies, though most scholarship attributes the first significant cavalry to the Assyrians of the early ninth century B.C. The history of cavalry in archaic Greece is complex and obscure in the extreme. The problem of scanty evidence is compounded by the difficulties in distinguishing cavalry from mounted hoplites, who would fight on foot, in archaic vase paintings. In addition, geographical variety was likely: although a small force did exist, real doubts remain about the very existence of an Athenian cavalry in the archaic period. The Thessalians, famous horsemen in the classical period, seem to have had cavalry from the eighth century on. Other states may have possessed cavalry and then abandoned it after the advent of the hoplite. Thus, Sparta’s hippeis, ‘horsemen’, consisted of an elite infantry unit in the classical period.

Weaponry varied between types of cavalry and even within a single unit. In classical Athens it seems that some riders were armed with throwing javelins and some with thrusting-spears, and some with both. In both cases, a short slashing-sword provided a back-up for close combat – since a long sword was hard to wield without stirrups. Special corps of horse-archers used bows and arrows. In 431 B.C., 200 of these horse-archers complemented Athens’ 1,000 regular cavalry.Cavalry men were well protected with armor. The extra weight of armor did not impinge as significantly on their horses’ mobility as on a hoplite and the expense of armor was less onerous for the wealthy men who typically made up the cavalry. Shields were rarely if ever used, since one hand was needed to hold the reins. Although horse armor was rare, riders were often protected with breastplates, helmets, greaves and boots. Although thigh, arm, and hand-armor existed, it does not seem to have been commonly used.

Peltasts

Although the clash of hoplites usually decided set battles, other foot soldiers often played an important auxiliary role and sometimes a decisive one. In some circumstances – for example, in rough terrain – these troops could rout unescorted hoplites. The most important of these, archers, peltasts and slingers, used missile weapons. Since they wore less armor, they were more mobile than hoplites. These types of soldiers were described by Thucydides as ‘prepared light-armed troops’ to distinguish them from the masses of poorly and irregularly armed combatants that sometimes accompanied a hoplite army and helped in ravaging the enemy’s countryside. These latter men were usually drawn from the city’s poorest class. Many may merely have thrown stones. Although a fist-sized stone thrown into the unprotected face of a fourth-century hoplite could knock him out, it seems in general that such generic light-armed soldiers were of little weight in battle. On the other hand, peltasts, archers and slingers were often highly trained and important. Spear-throwing specialists were often referred to as peltasts, since they carried the pelt’e, a crescent-shaped shield of Thracian origin that protected the arm and shoulder. This shield was light and suited to parrying missiles. Spear-throwers were also called akontistai, after the two light throwing spears, akontia, which they carried. A throwing strap imparted spin and made for a smoother and thus more powerful and accurate throw. Peltasts were occasionally depicted in hand-to-hand combat and unlike other light-armed troops could sometimes hold a line against cavalry and, on rough ground, even against hoplites. They carried a short slashing-sword as a secondary weapon.

Peltasts excelled at quick sallies, ambushes, reconnaissance missions, occupation of strong points and protecting or attacking marching routes. They tended to be particularly deadly in rough terrain, where hoplites could neither maintain their formation nor catch the quicker peltasts. In actions requiring speed and whenever an army had to move through the hills rather than staying in the plains, peltasts were useful.

Archers

Archers were naturally lethal against other light-armed troops who lacked protective armor. As hoplite armor became lighter over time and elements were discarded, hence archery became more of a threat. In open country, mounted archers could maintain their distance from the enemy infantry while continuing to shoot at them. Another important use of the bow was in sieges, either to clear the walls or to inflict injuries on the attackers.

Athenian triremes (naval ships) carried four bowmen. These could wreak havoc if they hit just a few of the entirely unarmored crew. To protect against this, linen, felt or leather screens – of unknown effectiveness but likely to make it hotter and harder to breathe when rowing – were put up during combat. Archers at sea were also probably useful for killing the crews of rammed, half-sunk triremes or for enforcing their surrender.

Slingers

Slings were inexpensive weapons made from leather patches with strings of sinew or gut attached to opposite ends. After loading the patch and spinning it around, the slinger released one string and the missile flew off. Rounded stones or balls of baked clay could be used. Heavy stones, some the size of a fist, might do considerable damage, Ancient sources insist that slingers had an effective range of about 200 meters and could outdistance archers.

Slingers possessed many of the same virtues and drawbacks as archers: easily overrun on their own, they could be an invaluable complement to other forces. Slingers fought best on rough ground or against other light armed troops or against cavalry with its unprotected horses. Slingers were not usually arrayed as closely as archers, since they needed room to swing their slings. Slingers helped in the attack or defense of walled cities. They served on triremes to harass other ships. Despite its low status, the sling’s usefulness was such that Plato includes training with the sling among the skills that children in the ideal state of the Laws should learn. 10

Male Companions

The male companions for the most part, seemed to have been the type of adolescents “just coming into the bloom of youth” that Greek paiderastai preferred. 11 The number of male companions which remained with the army for the duration of the campaign is uncertain, though it might perhaps be more appropriate to think in terms of many dozens rather than hundreds. The shared trials of the march to the sea evidently created affective bonds between the young captives and their erastai (older partner).

Boys whom the Cyreans acquired were most likely included in soldiers’ groups of comrades. Probably they marched, ate, and slept with ‘their’ soldiers. If they were trusted, they might become helpers in the daily tasks, as well as sexual partners for the men who acquired them. Over time, such youths could come to be seen as valued members of a group, perhaps even to the point of being provided weapons.

Female Companions

Most of the women accompanying the army were initially captured on the Mesopotamian plain; Xenophon called them as “the beautiful and tall women and girls of the Medes and Persians,” as with male companions. The seized female captives were sold as slaves or exploited as sexual objects. Forcing young boys in to sexual acts, and seizing young beautiful girls for wealth and personal lust were few of the disgraceful acts committed by the ancient Greek military. Those soldiers felt no shame while committing such heinous crimes against humanity. This terrorism was not only endorsed by the Greeks, but by the other ancient civilizations as well.

Navy

Thucydides, while commenting on the Greek navy, stated the following words:

'There are three considerable naval powers in Hellas - Athens, Corcyra, and Corinth'. 12

At the outset of the Peloponnesian War the Athenian navy was the largest in the Greek world, with no fewer than 300 triremes 'fit for service'. The nearest rival was the Corcyraean navy, which had 120 triremes, and Corcyra was allied to Athens. In addition, Athens could employ ships from Chios and Lesbos; 50 triremes from these two island states, for example, joined in the attack on Epidauros in 430 B.C. The Athenians naturally could not man all their ships at any one time - apart from the cost, 300 triremes would have required 60,000 able-bodied seamen. But the existence of this huge number of seaworthy hulls gave them a substantial reserve. The revenue from the empire also enabled them to accumulate a reserve of 6000 talents – enough to keep all 300 triremes in operation for 20 months – and imperial tribute came to 600 talents a year. 13

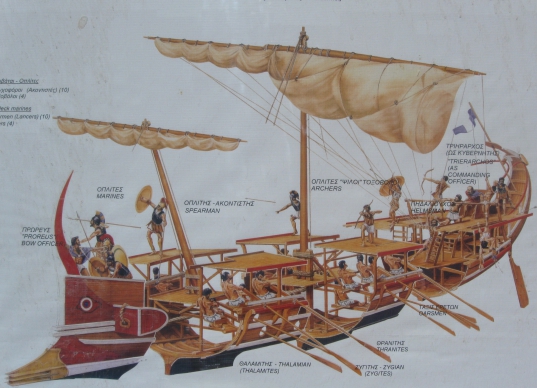

Warship

By the end of the 6th century B.C., triremes were the most common warship in the Mediterranean. The warship could have had two banks of oars on each side, but three banks of rowers, with one bank being central to the ship and pulling two oars instead of one. The Athenian navy was based at Piraeus, with over 370 ship sheds in its three harbors. Excavations of ship sheds at Piraeus harbor have provided maximum dimensions of 121.5 ft. (37 m.) long and 9.9 ft. (3 m.) wide at the bottom for the triremes based there.

Athenian naval records show that oars were 13.2–14.7 ft. (4–4.5 m) long. There were three types of oars: thranite, zygian and thalamian. The lowest level of rowers were the thalamites (thalamitai). There were 27 thalamites on each side, and they worked their oars through ports close to the waterline. The second level of rowers were the zygites (zygitai), of which there were also 27 on each side. The top level of rowers were the thranites (thranitai). There were 31 thranites on each side, and they rowed through an outrigger, which was an extension from the side of the ship that provided greater leverage for the oars.

The trireme was steered by a pair of steering oars at the stern, and it had a pair of anchors at the bow. They had a bronze-plated ram projecting from the bow at the waterline. Earlier triremes apparently had no deck or were only partially decked. Later they were decked right across to accommodate more armed men. Triremes still had a mast and sail like earlier ships, but before battle these were left ashore to lighten the load; the battle speed of a trireme depended only on the rowers. Because there was little room for supplies on board these ships, they were usually beached each night in order to obtain food and water.

The need for warships to frequently put into shore (usually every night) to take on water and supplies restricted the possibilities for an elaborate and prolonged strategy. The two main methods of attacking a ship, ramming and boarding, determined naval tactics. For example, the Athenian fleet carried relatively few marines, and the emphasis was on ramming rather than boarding. Tactics were generally simple, and the outcome of a battle depended on the success of individual ships.

For ramming, a ship would try to hit an enemy ship at a vulnerable point along the side and then pull away in order to get up sufficient speed to ram again. If the attacking ship could not pull away, marines from both ships would try to board the other and take it over in hand-to-hand fighting. For attempts at boarding, many methods of locking the two ships together were used, such as grappling hooks and ropes. As ships approached each other, missiles such as arrows and javelins were discharged. Tactical maneuvers were developed to maximize the chances of ramming, while other maneuvers attempted to foil such tactics. The periplus (periploos; literally, sailing around) was the simplest form of maneuver and was carried out by a fleet that outnumbered its opponent. Its superior numbers were used to outflank the line of enemy ships. Most of the fleet retreated, keeping their rams facing the enemy ships. Meanwhile their flanking ships rammed the side of the outermost ship in the enemy line, leaving the next ship exposed to similar attack. Once this flanking maneuver had been carried out, the entire fleet would attack. Another tactic was the diekplus (diekploos), which was used by a fleet of more maneuverable ships to break up a formation of enemy ships. This maneuver started with the attacking ships approaching the enemy line one after the other, in line-ahead formation.

The leading ship would make a sharp turn into one of the enemy ships, shearing off its oars on one side and leaving it stranded for the next ship in the line to finish off. This maneuver could be forestalled if the formation under attack consisted of two lines of ships, one behind the other, so that the ships in the second line could deal with the attacking ships once they had lost their speed. However, dividing a fleet into two lines meant that it was vulnerable to the periplus. The kyklos (circle) was a defensive formation adopted by slow or outnumbered fleets when attacked. The ships formed up in a circle with their rams pointing outward, making it very difficult for an attacking fleet to gain any advantage.14

Battle Tactics

Phalanx

George Grote described the Greek Phalanx as:

“The Hoplites, or heavy-armed infantry of historical Greece, maintained a close order and well-dressed line, charging the enemy with their spears protended at even distance, and coming thus to close conflict without breaking their rank: there were special troops, bowmen, slingers, etc. armed with missiles, but the hoplite had no weapon to employ in this manner”15

Warfare changed with the introduction of the double-grip hoplite shield and the tight formation of the phalanx at the beginning of the seventh century. In the new fighting style the warrior substituted for his pair of throwing spears a single heavy thrusting spear. The new shield, which was much wider, heavier, and more difficult to wield than a single-grip model, only made sense in close ranks, where one soldier sought cover for his vulnerable right-hand side behind the redundant half of the shield of the neighbor on his right. Therefore, soldiers arranged themselves in orderly rows with about three feet between them and in columns about (usually) eight men deep. The phalanx required many more men and much greater cohesion than the open-order combat of the Dark Age. It was essential for each soldier to keep his assigned place in the formation in order to provide cover for his neighbor and to make it possible for his side to break through the opposing ranks of the enemy. 16

While the phalanx could withstand attacks from cavalry and lightly armed skirmishers, it was too slow and clumsy to be effective against them. Adding cavalry and lightly armed troops to the hoplites of the phalanx gave it a measure of flexibility and also some protection for its flanks. The lightly armed skirmishers could harass the opposing phalanx or protect the flanks of their own phalanx, while the cavalry harassed the enemy. However, the outcome of the battle still depended on the phalanx itself. Usually both sides had cavalry and lightly armed skirmishers, so the advantage of such troops was reduced. 17

Famous Wars

The Battle of Marathon

The Persians attempted to invade mainland Greece twice – once in 490 and again in 480–479 B.C. These are conventionally called the First and Second Persian Wars. The key battle of the first campaign was Marathon. Its strategic effect was limited, for it did nothing to prevent the second invasion which came a decade later. The moral effect was enormous. It was the first time a Greek army had successfully faced the Persian enemy and demonstrated the superiority of hoplite tactics and equipment. 18

The Persians crossed the Euripus, and landed on the plain of Marathon, twenty-two miles from Athens. The ruin of Athens was certain if they waited for their town to be besieged; nothing but a victory in the field could save them from slaughter and captivity. They marched out, 9000 heavy armed men under the command of Polemarch and encamped on the hills overlooking the plain of Marathon. The army of the Persians that had wrought such ruin upon Ionia lay below them on the plain between the mountains and the sea. Sparta promised help but delayed sending it and the Athenians were alone in their desperate peril. At this moment, the little army of the citizens of Plataea, only a thousand in all, came to help the Athenians.

Still, the Greek army totaled up to 10000, and five of the generals thought that they ought to wait till help came from Sparta. The leader of the other five was Miltiades (who escaped from Persians and had been elected as strategus in Athens). Miltiades knew that there were traitors among the citizens, and feared that they would break up the army if fighting was delayed. Therefore, though the Persians were ten times as numerous, he urged immediate battle, and when the votes of the ten strategi (generals) were equally divided, the Polemarch gave his casting vote for battle. The generals gave up each of their own day’s command to Miltiades; and Miltiades, when the right time came, drew up the army in line for battle. After the generals had addressed their tribesmen, the battle signal was given and the whole army, raising the battle cry, charged down the hill upon the Persians. In the struggle, the center of the Greek line was driven back, but the two ends carried everything before them, and turned and attacked the Persians in the center. The Persians gave way, and fled for refuge to their ships, or were driven in to the marshes by the shore. Six thousand Persians and only hundred and ninety-two Athenians fell in the battle. Either before or immediately after the battle, a bright shield was seen raised on a mountain by Athenian traitors as a signal to the Persians that there were no troops in the city.

Miltiades instantly marched back to Athens. Soon after he reached, the Persian fleet approached, expecting to find Athens without troops. But when the Persians saw the men who had just fought at Marathon were ready to fight them again, they sailed away, and the whole armament returned to Asia.

The battle of Marathon was glorious to Athens and Plataea; and though the number of Greeks who fought and died in it was small, still it is one of the most important battles in all history. If this battle had not been won, Athens would have been captured by Persia; and the rest of Greece would have probably submitted. 19

Battle of Thermopylae (480 B.C., the Second Invasion):

Ten years after the defeat at Marathon, the Persian invasion of Greece was resumed by King Xerxes in 480 B.C. A Spartan, Leonidas led the Greek army to block the Persian advance at the pass of Thermopylae and Persian King Xerxes was leading a vast army overland from the Dardanelles, accompanied by a substantial fleet moving along the coast. His forces quickly seized northern Greece. The alliance of Greek city-states, led by Athens and Sparta, then tried to halt Persian progress on land at the narrow pass of Thermopylae and at sea nearby in the straits of Artemisium.

Leonidas had perhaps 7,000 men and faced some 70,000 enemies. The armored Greek infantry, held a line only a few dozen yards long between a steep hillside and the sea. This constricted battlefield prevented the Persians bringing their superior numbers to bear. The Greeks threw back two days of fierce Persian attacks, imposing heavy casualties while suffering relatively light losses themselves. Xerxes despaired of a breakthrough until he learned of a hill path that his troops could use to outflank the enemy line. On the third day, the Persians attacked via this route, brushed aside the Greek flank guard, and annihilated the parts of the Greek army that did not withdraw in time.

Leonidas and his 300 men bodyguard are said to have refused to retreat because it was contrary to Spartan law and custom. They staged a final suicide attack in which they were wiped out. Meanwhile, the largely Athenian Greek naval force received news of the defeat at Thermopylae and withdrew from Artemisium after a drawn battle with the Persian fleet. Overall, the losses were as follows: Greek, 3,000; Persian, up to 20,000. 20

The Peloponnesian War

When war broke out between Athens and Sparta, few Greeks foresaw that it would be different from any war they had ever experienced or even imagined. The twenty-seven-year conflict cost thousands upon thousands of lives and proved a stern lesson. It enhanced many of the worst features of Greek society— competitiveness, jingoism, lack of compassion, and gross disregard for human life.

The Periclean Strategy and the Plague

Pericles devised an ingenious strategy for winning a war he conceived as essentially defensive, and it is a measure of his influence and eloquence, that he was able to persuade his fellow Athenians to do something so conspicuously at odds with human nature. Harassing Peloponnesian territory with their navy, the Athenians declined to participate in hoplite battle with the Spartans. At Pericles’ instigation, the Athenian farmers abandoned their land, taking with them what few household goods could be loaded on wagons, and huddled with the city-dwellers inside the Long Walls that linked Athens to Piraeus. These walls, Pericles rightly perceived, made Athens an island. Food and other necessary goods would continue to be imported by ship from the different parts of the empire. The enemy, Pericles calculated, would tire of ravaging the land when nobody came out to fight. Seeing that the superior training and numbers of their infantry would do them no good, they would soon sue for peace. The Spartans, meanwhile, conjectured that the Athenians would grow restive cooped up in the overcrowded city throughout the campaigning season and, seeing their land being ravaged, would be unable to tolerate the frustration. They foresaw one of two consequences: either the Athenians would seek peace or they would overrule Pericles and come out to fight. In foreseeing that the enemy would give up after a couple of years, both sides miscalculated badly, but there was nothing intrinsically foolish in their thinking.

It was with reluctance and apprehension that the Athenians abandoned their homes and the familiar temples nearby, and when the farmers arrived in Athens only a few were able to find shelter with friends or relatives. Most had to seek out empty space in the city or bunk down in temples and shrines. Some wounded up spending the summer campaigning season in the towers along the walls. Fortunately, the Athenians thought, the war would not last too long; but of course, the Spartans knew this was just what they were thinking.

Though the first year of the war saw few casualties, by tradition the Athenians held a public funeral for those who had been killed. The next year brought a horrific surprise: a ghastly plague that attacked the population of Athens. Its origin was unknown, typhus probably or perhaps smallpox or measles—but it spread rapidly in the crowded, unsanitary environment of a city packed to capacity and beyond. Probably about a third of the populace died. Thucydides, who himself fell ill but recovered, took pains to record everything, he could do, about the course and symptoms of the illness so that it would be possible for readers to recognize the disorder should it ever reappear: he reported oral bleeding, bad breath, painful vomiting, burning skin, insomnia, memory loss, often fatal diarrhea and went on to describe the way in which people reacted to the disease.

Demoralized by the plague and frustrated by being forbidden to march out and offer battle, some Athenians tried to open negotiations for peace with the Spartans, ignoring Pericles’ cautions against this and in fact voting to depose him from the strategia (bringing forward some charge against him, as was common in Athens when politicians had ceased to please their constituency). Nothing much happened when Pericles was out of office except the long-awaited surrender of Potidaea. Finding that other leaders conducted the war no better, the Athenians returned Pericles to office at the next elections. Then he caught the plague and died. 21

After ten years of war, Cleon, the chief of war-like and imperialistic party was killed in Thrace and the power was passed on to Nicias, a man of small ability and a lover of peace. Sparta and Athens concluded a peace treaty and even formed an Alliance. This peace, which dated back to 421 B.C. was called the Peace of Nicias in history.

The peace did not last long. The Persian specter again raised its head in the east, and Persian gold found easy access to the pockets of the orators who attacked Athens in the Allied cities. Nothing but complete success could save Athens. A partial victory was little better than defeat, this point of view was expressed in set terms by Alcibiades, the Nephew of Pericles, an able general and dexterous politician. He thought that decisive success was attainable only by complete control at sea, and for this purpose, it was necessary that the Greeks in Italy and Sicily were included in the Athenian confederation. This was the design of Alcibiades, and if this was successful, it could bring certain victory. Still, the plan didn’t work out because his opponents persecuted him on a frivolous charge and then prevented an investigation while he was in office. Due to this, he fled to Sparta and revealed all the details of the plans to them. Nicias was not able to devise a new strategy, and made a lot of errors in following the current plan. Since Sparta was now aware of the Athenian plan and its weak points, it sent reinforcements under a competent general to Syracuse and the affair ended with the complete destruction of the army and navy of Athens in 413 B.C.

After the expulsion of Alcibiades, the Athenians made one more great effort. An Athenian fleet was now sent to defend the Hellespont and successful in the beginning. The Spartans were defeated at Arginusae in 406 B.C., but since this battle was fought during a storm, many Athenian sailors drowned in the sea. The failure of the generals to rescue their drowning men caused an explosion of anger in the popular assembly at Athens. The generals were deprived of their command and those generals who came back home were put to death. This was the major cause among others due to which Athens was defeated decisively at Aegospotami near the entrance of the Hellespont.

With this, the last hope of Athens perished. It was forced to accept the terms of peace dictated by Sparta in 404 B.C. The walls of the Piraeus were levelled, and the walls connecting the fortification of Athens were also destroyed. The Athenian naval fleet, with the exception of twelve ships was destroyed and Athens was forced to join the Lacedaemonian league, which was completely dependent on Sparta. 22

The Battle of Salamis

This battle started on the 20th of September 480 B.C., on an Athenian holy day. On the evening of this day, a figure of the god was carried in a grand festive procession to Eleusis, and the torches burned brightly along the sacred bay. While Themistocles was encouraging his fellow citizens for the decisive fight, there arrived from Aegina, the vessels with the sacred figures of the Aeacidae. An ardent desire for the battle spread through the Greek ranks, and when the Persians saw them, they were surprised to see Greeks ready for battle.

It was the Persians who made the first general attack. The Hellenes retreated upon the Salamis, but in perfect order, and the prows of their vessels faced the enemy at all times. The fight began with single assaults, bold commanders dared to advance beyond the line, and drew the rest in to the hand to hand contest. Thus, the battle became general and the Greek advantage became clearer.

The Barbarians (Persians), who entirely depended on their numbers, fought without any systematic plan or order, while the Hellenes, particularly the Aeginetans and the Athenians fought in proper formations. The vessels of the barbarians were floating houses filled with troops, while the vessels of Greeks were used as weapons of offense. Their courage rose with every collision which sunk a hostile vessel, with every successive sweep which broke the oars of their adversaries. Towards noon, the air and sea became disturbed, and the troubles of the enemy increased. Since the Persian fleet was drawn up in three lines, their heavy vessels were unable to move freely, and the ships which were damaged were unable to retreat or make way for fresh vessels to advance. The Persians became more frightened when they saw their inevitable death in the waters before them. The Greeks on the other hand fought with ease and agility.

Once Ariabignes, the admiral and brother of the king, and other men of eminence fell in the fight, the Persian fleet lost coherence, and the ships, fearing their destruction began to retreat in the direction of Phalerus, but even their retreat resulted in death and ruin. The Athenians pursued the fleeing Persian fleet, and attacked them continuously, which resulted in a big loss for the Persians.

In this situation there was no time for the Persians to take on board the troops which had been landed on Psyttalea to close the outlet of the bay against the Greeks. Aristides rapidly collected a band of armed citizens who were viewing the naval battle as spectators. These soldiers were transported to that island in which the Persians had closed the outlet of the bay. Since the island with its low bushes and branches, offered no protection to the masses of the Persians, a whole Persian army division was lost to the Athenian sword. By nightfall, the land and the sea were littered with broken mass of Persian vessels and corpses, and the battle was won by the Athenians. In gratitude for this victory, the memorial festival of the victory was connected with the moon-goddess. 23

The battles fought by ancient Greece were mostly for self-defense or for expansion of territories for material resources. One of the weaknesses of their military was that their military and navy was divided like the city states, and sometimes the army was used to inflict cruelty on its neighboring Greek states. Furthermore, the moral training of the Greek soldiers was non-existent. If these armies had defended the rights of the people and ended oppression by fighting in the way of God Almighty, they could have remained unbeatable, but since they used their energies for mundane purposes only, they were comprehensively defeated later on.

- 1 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 94.

- 2 Victor Davis Hanson (1999), The Wars of the Ancient Greeks, London, U.K., Pg. 18.

- 3 Paul Robinson (2006), Military Honor and the Conduct of War, Routledge, New York, USA, Pg. 14.

- 4 Arnold H. Heeran, (1842), Translated by George Bancroft, Ancient Greece, John Childs and Son Printers, London, U.K., Pg. 154-155.

- 5 Chabrias, was a mercenary who fought with distinction for the Athenians. Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/biography/ Chabrias: Retrieved: 18-04-2019

- 6 Victor Davis Hanson, (1999), The Wars of the Ancient Greeks, London, U.K., Pg. 13-15.

- 7 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins, (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 94.

- 8 David Sacks (2005), Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World (Revised by Lisa R. Brody), Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 163-164.

- 9 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 96.

- 10 Phillip Sabin, Hans Van Wees and Michael Whitby (2007), The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K, Vol. 1, Pg. 117-124.

- 11 Pederasty in ancient Greece became a socially recounted romantic relationship between a grownup male (the erastes) and a younger male (the eromenos) generally in his teens Martti Nissinen (2004), Homoeroticism in the Biblical World: A Historical Perspective (Translated by Kirsi Stjerna), Augsburg Fortress, Minnesota, USA, Pg. 57. It changed into typical practice of the Archaic and Classical periods. The impact of pederasty on Greek subculture of these durations changed into so pervasive that it's been referred to as the major cultural account of totally free relationships between residents.Some researchers discovered its starting place in initiation ritual, especially rites of passage on Crete, wherein it changed into related to entrance into army lifestyles and the religion of Zeus. It had no formal existence within the Homeric epics, and seems to have developed in the overdue 7th century B.C. as an aspect of Greek homo-social culture, which was characterized also by athletic and artistic nudity, late marriage for aristocrats, meetings, and the social seclusion of women. Beert C. Verstraete & Vernon Provencal (2005), Same-Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West, Harrington Park Press, New York & London, USA & U.K, Pg. 17.

- 12 Thucydides (1996), The Landmark Thucydides (Edited by Robert B. Strassler), Free Press, New York, USA, Pg. 24.

- 13 Nic Fields (2007), Ancient Greek Warship, Osprey Publishing, New York, USA, Pg. 33.

- 14 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 128-131.

- 15 George Grote (1846), A History of Greece, John Murray, London, U.K., Vol. 2, Pg. 106.

- 16 Donald Kagan & Gregory F. Viggiano (2013), Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, USA, Pg. Xi-Xii.

- 17 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 106.

- 18 Nicholas Sekunda, (2002), Marathon 490 BC, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, United Kingdom, Pg. 7.

- 19 Barne’s One Term Series (1883), Brief History of Greece, A. S. Barnes & Company, New York, USA, Pg. 113-114.

- 20https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Thermopylae-Greek-history-480-BC Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): Retrieved: 16-05-2017

- 21 Sarah B. Pomeroy (2004), A Brief History of Greece: Politics, Society and Culture, Oxford University Press, New York, USA, Pg. 200-204.

- 22 M. Rostovtzeff (1926), A History of the Ancient World (Translated by J. D. Duff), Oxford at the Clarendon Press, Oxford, U.K., Vol. 1, Pg. 278-281.

- 23 Barne’s One Term Series (1883), Brief History of Greece, A. S. Barnes & Company, New York, USA Pg. 118-120.