Educational System of Ancient Greece – Athens and Sparta

Published on: 15-Jun-2024(Cite: Hamdani, Mufti Shah Rafi Uddin & Khan, Dr. (Mufti) Imran. (2020), Educational System of Ancient Greece, Encyclopedia of Muhammad  , Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 196-210.)

, Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 196-210.)

Education is the method of facilitating, and the acquisition of knowledge, capabilities, values, beliefs, and habits. Educational techniques include storytelling, dialogue, teaching, education, and directed studies. Education frequently takes place under the guidance of educators, but newcomers might also educate themselves. Education can take place in formal or informal settings and any procedure that has a formative impact at the manner of one’s thinking, feeling, or acts can be taken into consideration as educational. It is not merely restricted to schools, colleges, universities ¬¬or other centers as people of the modern age think, in fact, any place where a form of learning is imparted, that place is called an education center. In the words of Thomas Davidson:

“Education is the process by which a human being is lifted out of his original to his ideal nature, and is something which every human being ought to claim and strive after.”1

This process of education is not a new phenomenon, and its antiquity is immeasurable because, from the beginning of time, mankind has been learning in one form or the other. Overtime, methodologies have evolved, but the aim has remained the same.

In order to ensure the survival and transcendence of any civilization or culture or religion, its teachings must be imparted to the people, otherwise, the learned will eventually perish one day, hence the treasure of their knowledge would be lost forever.

The art of teaching is of great antiquity and probably as old as human culture itself – for existence of any art, skill or body of knowledge implies a teacher to transmit it. There is ample evidence in Homer of the skill of the Greeks in early times in such activities as shipbuilding, carpentry, metalwork, storytelling, and poetry, all of which presuppose a long tradition and therefore the teaching of one generation by another. 2 From ancient Greece, all the streams which swell the current of modern civilization have proceeded. Greek philosophy, painting, architecture, history, sculpture, poetry and oratory have furnished suggestion and inspiration for all the centuries since then. 3 The educational system of the Greek was indeed some inspiration for some people, but it cannot be forgotten that this educational system was unable to produce students which could ensure the existence and sustainability of a prosperous society because education was merely gained for mundane benefits.

Education in Greece

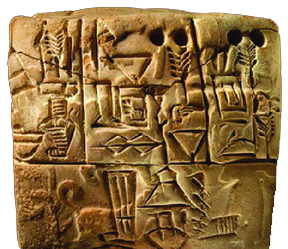

Surviving public inscriptions and historical anecdotes suggest that, in the more advanced Greek states, a majority of at least the male citizens could read and write by around 600 B.C.—barely 175 years after the Greeks had first adapted the Phoenician Alphabet. The impetus for this learning was probably not love of literature but the necessity of trade—a need that included the middle and lower-middle classes. 4

The history of Greek education – that is, of education in free Greece – is divided in to two fairly distinct periods by two contemporaneous events, the conflict with Persia and the rise of Philosophy. In the period previous to these events, education was for the most part, a preparation for practical life, and in the period succeeding them it, aimed more at being a preparation for dialogic life. In what is called the Hellenistic period, when Greece was no longer free, the latter tendency altogether gained the upper hand, for the reason that practical life, in the old Greek sense, no longer existed. 5

Paul Monroe in his book described it as:

“The generally recognized division of Greek education is The Old and The New, with the division point at the Periclean age or the middle of the fifth century B.C. Based primarily on the political periods of Greek history, this classification finds further justification in social, moral, literary, and philosophical changes, as well as in those relating to educational ideals and practices. Such a general division hardly suffices, however to trace the educational development along the lines just indicated, The Old education of the historic period is preceded by the education of the primitive and Homeric times, of the character of which much evidence can be drawn from the Homeric poems. This ‘Heroic Period’ is succeeded by the historic period of the Old Greek education which developed along two quite diverse lines, best known as Sparta and Athens.The New Greek period includes, first, the period of transition in educational, religious, and moral ideas during the age of Pericles. This is the period in which the new philosophical thought was developed and the new educational practices were shaped.”6

The Greeks began to take a practical interest in the education of their youth from an earlier time than other nations. It is with regard to the educational life of the Athenians that we have the most information up to at least the third century B.C. In later years, when Athens became the center of a new Hellenistic world, a tendency existed among nearly all Greeks, which grew stronger every day to adopt the principles and methods of the Athenian education.

Education in Athens

The education of the Athenians in the 5th century B.C. was, as is well known, a form of training, or education in the strict sense, rather than a system of instruction. It consisted of two parts – a training of the mind and character and a training of the body. Music in the broad sense comprised reading, writing, counting, singing and lyre or flute playing. 7

The Athenian education was in this as in other respects a reflex of the Athenian life. A national system of education in the strictest sense of the term was wholly foreign to the genius of the Athenian State. To force every citizen from childhood into the same rigid mold, to crush the play of the natural emotions and impulses, and to sacrifice the beauty and joy of the life of the agora, or the country-home, to the claims of military drill, were aims which were happily rendered needless by the position of Attica, as well as distasteful to the Athenian temperament. At the same time the State, while leaving the education of the citizen by the parents free, prescribed certain general rules. All had to be instructed in gymnastic and music. The Court of the Areopagus, moreover, as censor morum (a censor of morals) and guardian of the ancient constitution, exercised supervision and enforced certain laws. But the main controlling force seems to have been the force of public opinion. 8 According to Frederick, the aspects which were quite essential to a definition of the schools of Athens were:

1.The Education provided was cultural, not technical, directed towards character, training, and citizenship, not towards craftsmanship and personal profit.

2.The teacher was a professional, taking more than one pupil and offering instruction to all who could afford it. In this sense, he is to be opposed to the private tutor.

3.The instruction offered was given in some definite building or locality. 9

Schools

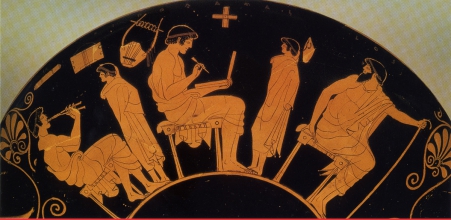

Literacy and numeracy were taught to boys at school. The earliest surviving reference to a school in the Western world occurs in the history of Herodotus (435 B.C.), in reference to the year 494 B.C. on the Greek island of Chios. Similarly, school scenes first appear on Athenian vase paintings soon after 500 B.C. Schools were private, fee-paid institutions. There were no state funded schools at this time and no laws requiring children to receive education. There were separate schools for girls, but girls’ schooling was generally not as widespread or thorough as boys. 10

Building and Equipment

About the physical conditions under which the letters were taught, scarce details have been found. In the reference that Herodotus makes to this type of school, he merely states that ‘the roof fell in on the boys as they were being taught’, so that we are left in doubt whether the instruction was being given in a building specially designed as a school, or whether some other building, private or public, hired or otherwise is made available for the purpose. Thucydide’s reference to the massacre at Mykalessos specifically mentions a ‘school’. The important fact which emerges from the references quoted is that schools did exist, and their number varied from sixty to a hundred and twenty, and we are not sure that whether they were located in Athens or how many teachers were employed in them.

The furniture of those schools was not very elaborate, it consisted of chairs for the masters and stools for the pupils. There were no desks, the pupils wrote with tablets resting on knees. Other equipment such as ink, rulers and so forth seem to have been provided. 11

Infant Education

The Greeks paid great attention to the appearance of their infants. At an early age the children wore shoes and their hair was twisted into artistic curls and drawn together over the forehead with a splendid comb, according to the fancy of mother and nurse. In the case of the girls, a slender make was aimed at by the use of stays, etc. From all this we see that the early childhood of the Athenian boy and girl was easy and pleasant.

The want of education among the Athenian women precluded their exercising much influence over the boys. But during the first seven years the mother and the nurse really laid the foundation of the child's education. Nursery rhymes, traditional stories in which animals played a part, thereafter the rich legendary, heroic, and mythical lore of the Hellenic races were imparted to the child. A poetic and dramatic cast of minds was thus given, to be nourished in future years by school teachings, public drama and civic festivals.

Primary Education

In the literary course under the Grammatist the first elements of reading, writing, and arithmetic were learned. Their details are as follows:

Reading

In learning to read, children learned synthetically i.e. they learned the individual letters first by heart, then their sounds, then as combined into meaningless syllables, and then into words. The analytic method of taking words first and analyzing the various sounds in them and teaching these on phonic principles, is held by some to have been practiced, but of this there is no sufficient evidence. "We," says Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who died about the beginning of the Christian era, “learned first the names of the letters, then their shapes and functions, then the syllables and their properties i.e. their accent and correct articulation, then kinds of declensions: lastly, the parts of speech, and the particular mutations connected with each, as inflexion, number, contraction, accents, position in the sentence; then, they begin to read and to write, at first in syllables and slowly, but when they had attained the necessary certainty, easily and quickly. It is said that the teacher wrote down what was to be learned and the children copied it. Plaques of baked earth on which letters and syllables were written or painted were in use also. The chief difficulties to be encountered by the child were the learning of the proper accent as these were not indicated by signs, and the separating of one word from another, as words were in those days written continuously without a break. Moreover, there was no punctuation. Reading was in these circumstances possible only when the sense was fully grasped, the want of separation of words and of punctuation may have contributed largely to mental discipline as well as to good elocution. The manuscripts were either folded or rolled. After the pupil was able to read, beautiful reading was practiced special attention being paid to the length and shortness of syllables and to the accentuation. Purity of articulation and accent were specially attended to. They were taught the raising and lowering of the voice and to bring out the melody and rhythm of the sentences, and all this with distinct articulation and expression.

Writing

In classical times, they used tablets covered with wax and a stylus or graver for writing. One end of the style was flattened for rubbing out what was written. These tablets were often diptychs and triptychs. For the children who could not yet write, lines were drawn and a copy set with the stylus; they imitated the copy, writing on their knees, since there were no desks. Some say they began by tracing the letters as lightly written by the master (the master guiding the hand); and this is highly probable. They drew straight lines with a ruler to keep the writing regular. Sometimes they carried the stylus over letters cut in wooden tablets. Plato thought very little of writing and considered that not too much time should be given to it. It was enough to be able to write legibly. When older, the pupils wrote with pen (calamus) and ink on papyrus or parchment. Owing to the cost of parchment they practiced on the back of leaves already written on one side.

Drawing

Drawing was much insisted on by Aristotle. It was not till his time that it began to be taught in the ordinary schools. But in the course of the fourth century B. C. it entered largely, into the general education according to Grasberger and others. It was first introduced from Sicyon. The drawing was on smooth boxwood surfaces white on a black background, or red and black on a white background. The instrument used was a pencil.

Geometry

As both Aristotle and Plato esteemed geometry as a school subject, it would appear that it was not till the later period of Athenian education (end of 5th century B. C.) that it was introduced into the schools. Geography was sometimes taught and maps began to come into use about the time of Plato. 12

Secondary Education

At fourteen or soon after, it was usual for the ordinary course of letters and lyre-playing to terminate though the gymnastics lessons were carried on till old age. During the first three quarters of the fifth century, the lad, on leaving the school was left to live more or less as he pleased. Rich boys spent most of their time in athletic pursuits such as riding and chariot driving while the poor ones settled down to learn a trade.

But with the Periclean age, a violent desire for a further course of intellectual study arose, and a system of secondary education arose to occupy the four years which elapsed between the time when the child finished his primary education and the time when the state summoned him to undergo his two years of military training.

Hence, secondary education was imparted, not in the regular schools by regular, established masters, but by wandering savants who taught every conceivable subject, and were all grouped together under the general name of Sophists. From this category, the mathematicians and astronomers, who in all respects occupied the same position, were often excluded. But Aristophanes, taking a more logical position, included geometry and astronomy, among the subjects taught by the burlesque Sophists of the clouds. In fact, secondary education included any subject that the lad or his parents desired; and the wandering professors who imparted it, and even established teachers like Isocrates, who kept permanent schools at Athens, had the same system.

But the most important subjects naturally fell in to two major groups: Mathematics and Rhetoric. Mathematics, as may be seen from the Republic, was a part of secondary education, the science of numbers, geometry, and astronomy, with a certain amount of theory of music, which, due to Pythagorean traditions, was classed with mathematics.

Rhetoric, from the time of Gorgias onwards, formed a very large part of the secondary education. Isocrates was its greatest professor. He provided his school a course of three or four years for children to occupy their time till they were epheboi (adolescents).

Grammar was also taught, and the right use of words. Less usual subjects were geography, art, and metre. Logic was at its infancy, but the growing lad could practice himself in argument by listening to the disputes of the dialecticians. Current conversation was full of ethical and political discussions.

In the fourth century, there the schools of Plato and later of Aristotle and the lectures of Antisthenes the cynic in Kunosarges, and Isocrates taught political science. Children seem to have been expected to learn something, at any rate, of the laws of their country. They were taken up to the Acropolis to read as spectators in the law-courts, in order that they might gain an idea of legal procedure. Those who intended to become speech writers for the courts would learn more. They would also attend some well-known writers like Lusias or Isiaos, and learn the art of forensic rhetoric. 13

Girls Education in Athens

For girls, Athens had a different system. An Athenian woman was essentially a housewife who spent her time at home. She was not a companion to her husband who spent the greater part of his life abroad, or a guide to her sons, who after the age of seven were removed from her care. Usually, girls were married early and her full training in household duties was regarded as the task of her husband, who thus had a better chance of molding her to his wishes. Hence, we see how the concept of life (narrow in this case) dictated the form of education.

Not allowing women access to education was akin to destroying future generations because the first person responsible for the upbringing of a child was a woman. If she remained illiterate then the child in her care could grow up without knowing any morals and various skills.

Education in Sparta

Sparta was a more liberal place from an educational viewpoint. People of Sparta were comparatively conscious for the education of their children and did a better planning than other states of Greece. Aristotle said:

“Sparta appears to be the only, or almost the only state, in which the law-giver has paid attention to the education and discipline of the citizens. In most states such matters have been entirely neglected, and every man lives as he likes, in Cyclops fashion, ‘laying down the law for himself and his spouse.”14

Education in Sparta was deliberately planned, designed, and controlled for a definite purpose. The life of the child began with the state’s decision as to whether the state had any use for him or not. When it had been decided that a child was to be kept, he was bathed in wine, for it was their superstition that wine so used, sent the weakly in to convulsions or unconsciousness, but tempered the body of the strong as steel. And there and then, the child’s education began.

For the first seven years of his life, the child was left at home, under his nurse. It was with the nurse that the training began. They taught them to be contented and happy, not to be dainty about their food, not to be afraid of the dark or in seclusion. So the nurse nurtured the child, even in his earliest days, into physical excellence and into that self contained courage for which the spartans were famous.15

At the age of seven, the child was consigned to the care of the state and subjected to the regular public education. Hence forth, he ate at the public table and slept in the public dormitory. Only half rations were granted and his bed was a mere bundle of reeds or rushes which he was compelled to gather for himself from the banks of Eurotas. No knife or instrument other than hands was allowed in obtaining them. In winter, thistle down was scattered among the reeds to inspire a feeling of warmth in the sleeper. For exercising his acuteness, the boy was often allowed only what he could steel. Adroitness was applauded if he was not detected, but was punished if discovered.

The head of the educational system was a superintendent, an eminent citizen specially chosen to look after the games and habits of the youths. His powers were quite extended, requiring a staff of assistants called moderators or chasteners, and whip carriers. Besides these officials, the youths were under the constant supervision of the older men, who regulated their play by well-timed praise or reproof. They were accustomed to stir up frequent disputes and conflicts among them to see who were brave or cowards. Besides, each boy had a special guardian (an adult) who backed him in his contests with other boys, stimulated his courage, and taught him to speak only when he had something to say, and generally formed his ideals. This relation, recognized by law was established by mutual choice, fortified by the disgrace belonging to the absence of such attachment in the case of either man or boy. Even though the boy was subjected to abuse, this practice was still the strongest character forming agency of the Spartan system. Such abuse also had negative psychological effects on the children due to which those children had uncontrolled tempers and were always hungry for a fight. Such children are a clear hazard for the society in every era. Children need to be treated with care and love so that they show compassion as well when they grow up. Moreover, their relationships with the pedagogs were unhealthy as well since their teacher mostly ended up sexually abusing the students.

At age twelve, the training increased in severity and took on more of a military character. At eighteen, the boys were admitted to the youth’s class (Ephebi), and for two years, were subjected to stricter discipline and greater drill. They were compelled to undergo strict examinations before the ephors (senior Spartan magistrates) once in ten days regarding their physical condition. Their clothing was inspected daily, and they exercised in gymnastics. Along with it, use of arms was taught under the supervision of five or six teachers.

David Sacks portrays it as:

“Wrestling and gymnastics were among the preferred disciplines. Militaristic states such as Sparta greatly emphasized sports as a preparation for soldiering; the rugged art of Boxing was considered a typically Spartan boy’s sport. Sparta was unusual in encouraging gymnastics training for girls.”16

At twenty, they were called ‘eirenes’, exercised alone, had influence over their juniors and were eligible for actual warfare. Their training was the endurance of hardship, coarse food, reed beds, and limited bathing. They practiced with heavy arms, danced the pyrrhic dance and manned the fortresses of the country. Not until the age of thirty did they attain their majority and admitted to citizenship. 17

Girls Education in Sparta

Spartan women were also permitted to public education as well. This was very radical as other Greek girls were not formally educated. They could not, however, use their education to have careers or earn money.

As part of a Spartan girls’ education, she would have been permitted to exercise outdoors, unclothed, like the Spartan boys, which was impossible in the rest of the Greek world. Not only would men and women not have been naked in public together, but a proper Greek woman would not usually set foot out of doors, other than to perhaps collect water from the cistern. Yet Spartan women not only exercised, they also participated in athletics, and competed in events like footraces.

It was seen as a guarantee that the strong and fit Spartan women would reproduce, and when they had babies, those babies would be strong warriors in the making. 18 The aim of these activities was to provide healthy environment to women so that they become stronger. However, these girls could have been provided a separate place with a female trainer to train them. Secondly, getting naked for exercise has never been compulsory. A person (man/woman) can easily exercise while clothed. This system was launched in Sparta, and managed to produce stronger women, but in reality, it destroyed the moral values and respect which were gifted to women by the Creator.

Girls have always been provoked in the name of expression of freedom of speech, living naturally and many other lures to wear minimal or no dressing. Humankind has forgotten that the first thing which Satan did to them was that he removed their clothing. It shows that the most favorite ploy of the devil and he has been using it since the beginning. Therefore, instead of endorsing and employing such methods, people who are known as or call themselves intellectuals need to give this matter some thought so that humanity is saved from this ploy of the Devil.

Spartan society was morally ill because they did not know the manner to live in to the society and to behave with respect to their women which needed to be respected according to the divine teachings.

Girls Education in Pythagorieo

Pythagorio was located at the ancient metropolis of Samos. Some ruins of the historical town are today integrated in current homes of Pythagorio. The historical town reached affluence round 530 B.C. below Polycrates tyrant. 19 At that time Samos became an effective nautical nation. This power led to richness and prosperity, which is obvious from exceptional works of the duration, along with the super aqueduct like the Tunnel of Eupalinos, temple of Heraion, and Samos harbor.

The Pythagoreans unlike Spartans, trained the mind along with the body of the girl. The admitted women were given full teachings in mathematics and music. Some of these women attained distinction in their city states 20 but they are scarcely mentioned in the books of Greek history.

Education System in Crete

In Crete the boys were retained in the family till their eighteenth year. At this age they were required to enter themselves (some say these associations were voluntary) as members of bands or troops to be trained in a severe course of gymnastic including archery, hunting, and military exercises. At this age also they were admitted to the public meals and allowed to listen to the conversation of the grown men. These bands, each with its own head, were under the general superintendence of an overseer appointed by the State. There was no gymnastic specialist employed as teacher, at least in the earlier times. Their literary education, so far as reading, writing etc., received little or no attention. But in connection with the Doric music which all learned, they became thoroughly versed in the laws. They also sang hymns to the gods, tales of heroes, and narratives of the great achievements of their ancestors. Their literary education thus really comprised music, religion, civic economy, history, and poetry in their rudimentary forms. 21

The musical education began generally about the age of thirteen. To the Greeks, the musical education for a gentleman means singing and playing upon the lyre and the flute or clarionet is commonly left to professionals. Strangely as it may appear to this enlightened age, the chief aim of musical teachings at Athens was the proper cultivation of feelings. There was no intention of turning out professionals, but of edifying the inner man. Side by side with the playing of the lyre, the pupils appropriately read and learned lyric poetry. 22 But history tells us that most of the times, their efforts went in vain because their generations still used to become savages that used to fight and brawl with other human beings for material gains only.

Universities

The universities of the Grecian world were outgrowths of the philosophical and rhetorical schools. While there were several such groups of schools, two alone were worthy of special mention and have been given the title of university.

The University of Athens resulted from the combination of three schools: The Academy, The Peripatetic School (name of the school founded by Aristotle), and the Stoic. Due to the war, all had been compelled to move in to the city. With the combination of the epheboi with the more intellectual work of the philosophical schools, a more permanent institution was formed whose head was elected by the Athenian senate. The boys were required to attend lectures in the three philosophical schools, and teachers of rhetoric and logic were added. Students came to this new school from abroad as well and many were ill prepared so this gave employment opportunities for numerous private teachers, tutors and assistants. In time, this grew up to an elaborate structure of a university as we know today.

The University of Alexandria, during the earlier Christian centuries, supplanted Athens as the intellectual center of the world. Under the influence of the Ptolemies (323-30 B.C.), the purpose of their master Alexander was to make this new city the center of Greek influence, power and learning. They founded a museum and library where men of letters and of science resided at royal expense. An extensive collection of Greek, Jewish, Egyptian and Oriental manuscripts were secured for this library.

Not only did Alexandria possess the manuscripts of Aristotle here all alone, but among all the institutions of higher learning, the Aristotelian method of investigation was employed.

Here, the Ptolemaic theory of the universe 23 was formulated. Here, Archimedes of Syracuse carried out most of his labors here and made many of his discoveries in physics. Even Euclid perfected that branch of mathematics here which bears his name. But it should be known that the work at Alexandria, like that in the Grecian philosophical schools, consisted mostly of the dreary comment and exposition of what the master or the corrupted manuscript version of the master said. 24

Professional Education

The Hippocratic tradition regarded medicine as fundamentally a technique for art and had to be taught and practiced like any other art. There was however, a tendency for it to be contaminated by philosophy which Hippocrates aspired to combat in his treatise on ancient Medicine. Plato placed the physician in the same category as the cook, the ship’s captain, the farmer and the shoemaker. ‘The Physician’, he says, administers the appropriate diet or remedies of knowledge of practical application. The long and complicated regimens which physicians prescribe are ridiculed in another passage of the Republic, where he says that such treatments were only for the wealthy. The poor should either recover on their own accord or end their troubles by dying. But the fact remains that the physician had to know how to prescribe regimens for his wealthy patients. Physicians learnt their craft like any other craftsmen through practice and association.

Teaching

The teaching profession was probably not held in very high esteem, but those who were forced to earn their living by teaching would learn their craft in the same way as medicos – by association, imitation and practice. For advanced teaching, as in Plato’s academy, Isocrates’ school for the career of a sophist a similar apprenticeship had to be served in a long association with the master until independence was achieved. The particular body of knowledge and the techniques of the particular school, which the scholar was attached needed to be thoroughly learned.

Law

Since Greek law did not allow advocates to actually appear for a client, the profession of the lawyer did not gain as much popularity in Greece as it did in Rome. Lawyers made a living by writing speeches for the clients. Such a speech writer was termed as a ‘logographos’. A logographos had to master a certain amount of practical psychology in order to be able to adapt to the speech and character of the client. He also had to learn the handling of legal arguments and phraseology.

His training was based upon the learning of a series of stock arguments, openings, perorations etc. This training was either provided by the senior logographi, the rhetorical schools or by the sophists. Antiphon’s tetralogies give us some basic idea regarding the type of rhetorical exercise which was practiced. Each of them consisted of four speeches. They consisted of the charges adduced by the accuser, the reply of the defendant, the second speech of the accuser and the second reply of the defendant. These speeches were mere skeleton speeches, stripped of all embellishments so that they could emphasize on the essential framework of a lawyer’s method of attack and defense.

Such was the choice of intellectual studies open to the youth of the fifth and fourth century Athens. A youth could take none of it, or as much as he could afford or desired. Apart from the formal instructions offered, he could hardly escape from the educational experience of living in the Athenian society by being exposed to its culture. 25

Education whether military, philosophical, mathematical or physical etc. was a primary aspect of every Greek’s life. The educational systems of the different city states varied due to their locations and their societal needs, hence we see that the Spartans had more emphasis on military education, whereas the Athenians focused more on other aspects. Girls didn’t have the same access to education as boys (with the exception of Spartan girls) because co-education did not exist, and boys were given special preference since they were the ‘bread earners’. It can also be seen that the people who had better skills and education, earned better than their peers. Therefore, anyone who could afford, opted to go for higher educational studies, while the poor struggled to earn their livelihood.

The ancient educational system of the Greeks produced a lot of development in various fields, but was imperfect and unjust in many ways since it was only accessible to those who could afford it. Education has always been a need which has been kept out of reach for most ancient and modern societies because it has been linked to material gain and only those people could attain it who were wealthy. In this manner, inequality started to spread and the rich started to become richer while the poor became poorer. Moreover, this educational system was completely devoid of moral and ethical teachings and has been one of the major contributing factors for ancient and modern savagery in the society where the juniors do not respect the elders and the elders detest the children. Morals have been corrupted to the extent it is considered ‘normal’ if a boy has sexual relations with his mother or even his sister, and unnatural phenomenon like homosexuality is not only accepted, but praised. In the name of betterment, development and progress, entire educational and then moral and social systems have been destroyed by the Greeks and those who followed them.

- 1 Thomas Davidson (1900), The Education of the Greek People and It’s Influence on the Civilization, D. Appleton and Company, New York, USA, Pg. 23.

- 2 Frederick A. G. Beck (1964), Greek Education 450-350 B.C., Methuen & Co. Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 72.

- 3 Frederick H. Lane (1895), Elementary Greek Education, C. W. Bardeen, New York, USA, Pg. 5.

- 4 David Sacks (2005), The Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 117.

- 5 Thomas Davidson (1900), The Education of the Greek People and It’s Influence on the Civilization, D. Appleton and Company, New York, USA, Pg. 53.

- 6 Paul Monroe (1905), A Text Book in the History of Education, The Macmillan Company, New York, USA, Pg. 61-62.

- 7 John W. H. Walden (1912), The Universities of Ancient Greece, George Routledge & Sons limited., London, U.K, Pg. 10.

- 8 S. S. Laurie (1894), The School Review: The History of Early Education: Hellenic Education, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 420-421.

- 9 Frederick A. G. Beck (1964), Greek Education 450-350 B.C, Methuen & Co. Ltd., London, U.K, Pg. 72-73.

- 10 David Sacks (2005), The Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World (Revised by Lisa R. Brody), Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 117.

- 11 Frederick A. G. Beck (1964), Greek Education 450-350 B.C., Methuen & Co. Ltd., London, U.K, Pg. 88-89.

- 12 S. S. Laurie (1894), The School Review: The History of Early Education: Hellenic Education, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 422-429.

- 13 Kenneth J. Freemen, (1912), Schools of Hellas, Second Edition, Macmillan and Co. Ltd, London, U.K., Pg. 157-162

- 14 William Barclay (1959), Educational Ideals in the Ancient World, Collins, London, U.K, Pg. 49, 63-64.

- 15 William Barclay (1959), Educational Ideals in the Ancient World, Collins, London, U.K, Pg. 49, 63-64.

- 16 David Sacks (2005), The Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World (Revised by Lisa R. Brody), Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 117.

- 17 Frederick H. Lane (1895), Elementary Greek Education, C. W. Bardeen, New York, USA, Pg. 32-36.

- 18 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): http://www.ancient.eu/article/123/ : Retrieved: 26-04-2017

- 19 Odysseus: http://odysseus.culture.gr/h/3/eh351.jsp?obj_id=19849 : Retrieved: 02-15-2018

- 20 Kathleen Freeman (1952), God, Man, and States: Greek Concepts, Macdonald & Co. Publishers Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 184.

- 21 S. S. Laurie (1894), The School Review: The History of Early Education. Hellenic Education, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA, Vol. 2, Pg. 337-338.

- 22 T. G. Tucker (1922), The Social and Public Life of a Classical Athenian from Day to Day, The Macmillan company, New York, USA, Pg. 185-186.

- 23 In astronomy, the Ptolemaic system (also known as geocentrism, or the geocentric model) is an outdated description of the universe with Earth on the center. Under the Ptolemaic version, the sun, Moon, stars, and planets all encircled the Earth. The Ptolemaic model served as the predominant description of the cosmos in many ancient civilizations. Modern Ptolemaic system which is called geocentrism is pseudoscientific which includes statements, ideals, or practices which can be claimed to be scientific and actual, within the absence of evidence accrued and confined by suitable scientific strategies.

- 24 Paul Monroe (1917), A Brief Course in the History of Education, The Macmillan Company, New York, USA, Pg. 76-78.

- 25 Frederick A. G. Beck (1964) Greek Education 450-350 B.C, Methuen & Co. Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 143-145.