Religious Rituals of Greece – Rituals, Festivals & Worship

Published on: 14-Jun-2024(Cite: Hamdani, Mufti Shah Rafi Uddin & Khan, Dr. (Mufti) Imran. (2020), Religious Rituals of Ancient Greece, Encyclopedia of Muhammad  , Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 135-157.)

, Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 135-157.)

Every religion of this world, regardless of its time, location or race, has always been comprised of two basic components, beliefs and practices. The Greek religion was no different. It had certain religious beliefs (as mentioned in the previous chapter), and practices in the form of religious code, festivals and rituals.

Since they didn’t have any guiding works of scriptures, like the Jewish Old Testament, the Christian Bible, the Muslim Quran, nor any strict priestly caste, their beliefs were based on mythical stories of gods and heroes.

The relationship between human beings and deities was based on the concept of exchange: gods and goddesses were expected to give gifts. Votive offerings were a physical expression of thanks on the part of individual worshippers. The Greeks worshipped in sanctuaries located, according to the nature of the particular deity, either within the city or in the countryside. A sanctuary was a well-defined sacred space set apart usually by an enclosure wall. This sacred precinct, also known as a temenos, contained the temple with a monumental cult image of the deity, an outdoor altar, statues and votive offerings to the gods, and often features of landscape such as sacred trees or springs. Many temples benefited from their natural surroundings, which helped to express the character of the divinities. 1

Temples

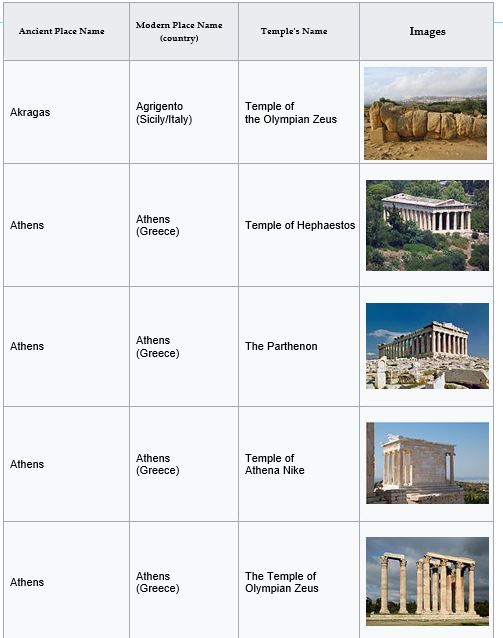

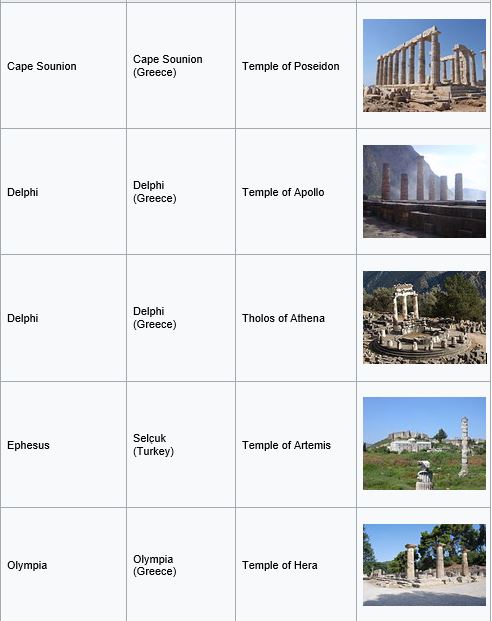

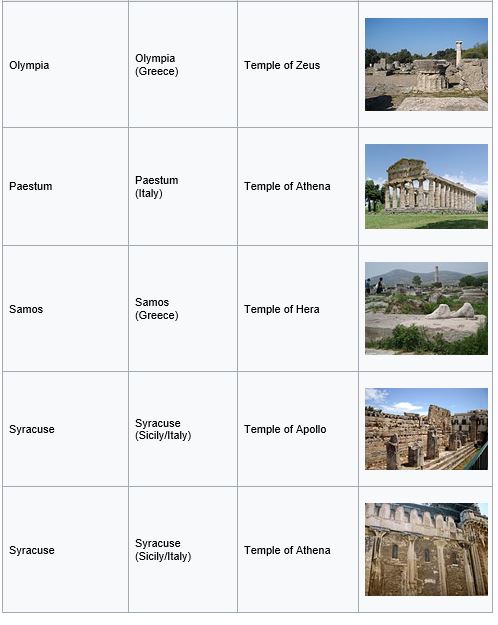

In Ancient Greece, the temple was the most important building. They were not used as places of worship but rather as monuments to their beloved god and goddesses. The earliest temples were either made by wood or mud bricks, but by 6th century BC, they were made by using marble and stone structures.

The major temples of ancient Greece can be seen in the table below: 2

Rituals

The Greeks had no central collection of sacred texts, such as a bible, nor a universal caste of priests to interpret and define orthodox religion. They demonstrated their beliefs and communicated with their gods largely through prayers, hymns, divination, sacrifice and votive offerings. It was believed that gods could intervene in human affairs and could be influenced by rituals, even though there was a distinction between the realm of gods and that of humans. Most rituals such as sacrifice were an attempt to please the gods. Such influence and intervention might be sought by simple prayers or by a combination of prayer, ritual and sacrifice. The religious festival was an example of such a combination and could include all methods of communicating with gods and propitiating them. Devotion to the gods was seen as regular performance of rituals, including various forms of prayer and sacrifice. Piety was defined by correct performance of these rituals, rather than by moral behavior. Most religious observance was probably performed at a local rather than city-state level. 3

Ritual in Homer was simple and uniform. It consisted of prayer, accompanied by the sprinkling of grain, followed by an animal burnt-offering. Part of the flesh was tasted by the worshipper and then made over by burning to the god; the rest was eaten as a banquet, with abundance of wine. The object was to "persuade the gods," and to a Northern god there was nothing more persuasive than an abundant meal of roast flesh and wine. The method of offering was by fire, because the gods were heavenly gods, and the sacrifice needed to be sublimated to reach them. 4

Worship in ancient Greece was sometimes conducted by the father on behalf of his household, by the king for his people, and by the magistrate for the state. When a father, a king, or a magistrate performed this sacred duty, he sacrificed to any divinity, whether god or goddess, as occasion demanded. On the other hand, worship was very often conducted by a priestly minister who was connected with a temple and was chosen for the service of a particular divinity.

According to Greek custom, gods were usually served by priests while goddesses were attended by priestesses. The statement of Fairbanks is as complete as any: “The choice of a priest needed to conform to conditions which differed with each shrine. Ordinarily the gods were served by men and the goddesses by women or vice versa, as at Tegea where a boy was priest of Athena, and at Thespiac where the priestess of Heracles was a young woman. 5

Prayers

Prayers in ancient Greece are known from ancient literature and inscriptions. They generally followed a formula and were highly structured, usually with three parts. They began with an invocation of the deity, referring to the relevant function or functions of that deity. This was followed by reasons why the deity should answer the prayer, often citing what the suppliant had done for the deity in the past, such as sacrifices, votive offerings and worship. The final part of the prayer was a particular request to the deity. Personal prayers were usually offered at the start of new projects, the beginning of a new day and the beginning of the farming season. Public prayers were offered at the start of military campaigns, athletic or dramatic contests, and political meetings. The division between prayers and curses could be very narrow; often the only difference was in what was being requested from the deity. It was believed that gods could provide protection and success for the living. Their prayers were often accompanied by sacrifice, and the gods were expected to listen and help. 6 Prayers were not concerned with the afterlife and tended to be requests for benefits for the living, such as success in war and love, a good harvest, good health and fortune, wealth and children. This concept was flawed as all the divine religions have repeatedly informed mankind that there is a life after this worldly life which would be everlasting and eternal. Islam teaches us that after the departure from the body, the soul continues to exist. It also informs us about the Day of Judgment when part of humanity will be sent towards the eternal destinations of paradise and the other part towards hell, but this concept was of little or no value to the Greek people.

In the main, the Greek worship was of a joyous, pleasant, and lightsome kind. The typical Greek was devoid of any deep sense of sin, did not think very highly of the gods, and considered that, as long as he kept free from grave and heinous offences, either the moral law or against the amour-propre of the deities, he had little to fear, while he had much to hope, from them. They prayed and offered sacrifice, not so much in the way of expiation, or to deprecate God's wrath, but seemingly in the way of piety, to ask for blessings and to acknowledge them. He made vows to the gods in sickness, danger, or difficulty, and was careful to perform his vow on escape or recovery. His house was full of shrines, on which he continually laid small offerings, to secure the favor and protection of his special patron deities. Plato says that he prayed every morning and evening, and also concluded every set meal with a prayer or hymn. But these devotions seem not to have been very earnest or deep, and were commonly hurried through in a perfunctory manner. It is an established fact that the Creator is the Supreme Being who is Independent in every way, hence the Greeks were unaware of the fact that the Creator did not need their obedience or prayers. In fact, it was humanity, who needed the support of Allah and therefore needed to submit to His will.

When a nation had transgressed, human sacrifices were not unfrequently prescribed as the only possible propitiation; if the case were that of an individual, various modes of purification were adopted, ablations, fasting, sacrifices, and the like. According to Plato, however, the number of those who had any deep sense of their guilt was few: most men, whatever crimes they committed, found among the gods examples of similar acts, and thought no great blame would attach to them for their misconduct. At the worst, if the gods were angered by their behavior, a few offerings would satisfy them, and set things straight, leaving the offenders free to repeat their crimes, and so to grow more and more hardened in iniquity. 7 Such corruption occurred in their minds because they believed that God was similar to them which is impossible even in theory. God is basically the source of all good and is not susceptible to any influence of any other being. Secondly, He is independent in every way, whereas the human is the complete opposite. Therefore, such atrocities can be expected from a human who is misguided, but expecting heinous acts from a God is nothing more than a delusion.

Hymns

Hymns were sung to the gods as prayers set to music, and there were several types of hymns, including paeans. The dithyramb was a choral hymn to Dionysus. There were also hymns for particular occasions, such as processions, and some were written to address a particular god about a specific subject. Singing of hymns by a trained chorus appears to have been a common element of communal worship, and it is likely that each sanctuary had its own set of hymns, probably used for festivals and special events, rather than as an act of daily worship.

Votive Offerings

Votive offerings or dedications were token gifts to the gods in gratitude for favors received and to ensure continuing attention from the gods. Some inscriptions give thanks for a gift or favor received, and also constitute a prayer for similar gifts or favors in the future. Votive offerings could be a part of what had been requested from the god or closely connected. For example, victorious soldiers often donated some spoils captured from the enemy, and winners of contests often dedicated part of their prizes. Votive offerings were made to mark important stages in life, such as births and marriages, to thank for having survived disasters, such as earthquakes and shipwrecks, and in gratitude for recovery from illness. Surviving inscribed inventories list votive offerings, giving additional information such as value and the name of the person who gave the offering.

Types of Offering

A great variety of votive offerings were existed in Greece. Almost everything could be used, from seeds and grains to massive statues, but some objects were specifically made as votive offerings. Votive offerings reflected the increase in prosperity from the 8th century BC. A variety of pottery containers were used (including specially made miniature pots), probably of less importance than the offerings of perishable foodstuffs or wine contained in them. These pots were often ritually broken to prevent them being taken back into everyday use after having been given to the gods. Other types of pottery were used as offerings, such as painted rectangular plaques and other terra-cotta models. Personal possessions were often dedicated to the gods. Soldiers might dedicate arms and armor, poets might give copies of their poems, athletes might dedicate athletic equipment, and women might offer spinning and weaving equipment and mirrors. Jewelry was commonly offered, more to goddesses than gods, and the size of some extremely large jewelry indicated that it was specially manufactured for votive offerings. Figurines in pottery and bronze were also popular, and some religious sanctuaries had their own manufacturing workshops. Human figurines predominated, sometimes representing deities, but more often representing the worshipper. Figurines of animals such as bulls, deer, sheep and goats, were also common. Statues were also dedicated, especially the kore. 8 Foodstuffs and other perishable offerings, such as flowers, continued to be dedicated, but have left no trace unless mentioned in surviving records. Hair was another perishable offering, frequently made at puberty and at times of crisis to a river god.

A particular form of votive offering, commonly made at healing sanctuaries in gratitude for a successful cure, consisted of anatomical models of parts of the body, such as hands, feet, legs, breasts, genitalia and heads. These represented the afflicted part that had been healed. Also given as offerings were images of the person cured and images of the deity that presided over the shrine. Most votive offerings were relatively small and were stored within the religious sanctuary where they had been dedicated. Thousands of offerings could accumulate, and special buildings were often constructed to house them. There were also larger and more elaborate votive offerings, such as sculptured reliefs dedicated to heroes, which were carved to portray scenes from the hero’s life, scenes of rituals and scenes of feasting. Another type of large votive offering was a bronze cauldron on a tripod; these cauldrons were everyday objects, but the ones specially made for the gods were much larger and elaborately decorated.

Washing

Before any sacrifice took place, the sacrificer needed to be ritually cleansed, which usually took the form of washing the hands or sprinkling with water. Hand washing was an essential part of the ritual of animal sacrifice; in classical times a distinctive metal vessel (khernibeion) was used for holding water for ritual washing and was portrayed in artistic representations of sacrifice. Perirrhanteria were raised stone basins holding water for ritual washing, commonly found in religious sanctuaries. 9

Sacrifice

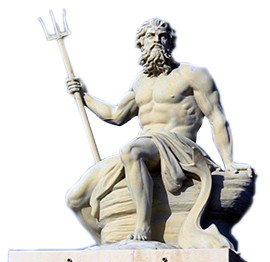

The rite of sacrifice—practiced in various forms by many ancient religions—probably dates back to Stone Age hunters’ rituals. The Greeks saw it as the essential way to win divine favor. “Gifts persuade the gods,” a proverb ran. Although “bloodless” sacrifices of grain, cakes, or fruit might be offered; a more significant act involved the slaughter of a domestic animal. The noblest victim was a bull; the most common was a sheep. Goats, pigs (according to all divine religions pigs are not eligible for being sacrificed due to its natural disgust), and chickens were also used. 10

Animal Sacrifice

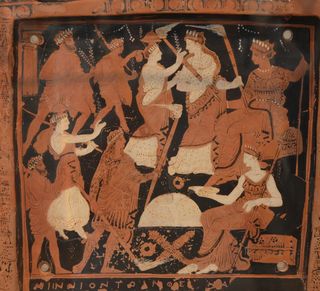

One of the most important parts of Greek religion was the sacrifice of animals to gods. Abundant references to such sacrifices exist in ancient literature and inscriptions. Animal sacrifices were also portrayed in art. Animal sacrifice formed the heart of the vast majority of Greek religious cults. Animals selected for sacrifice had to be without blemish. They comprised domesticated and wild animals, birds and sometimes even fish. Generally male animals were sacrificed to gods and female ones to goddesses. Light-haired victims were chosen for sacrifice to “bright” (celestial) deities, and black-haired victims were sacrificed to the dead and to the gods of the underworld, although there were many exceptions.

Animals unfit (or not used) for human food were sacrificed to specific deities. For example, horses were sacrificed to Poseidon and dogs to Hecate. 11 Homer gives details of the performance of an animal sacrifice. The sacrificer ritually washed his hands, and water was sprinkled on the victim. After a holy silence was declared, it was followed by a prayer by the officiate, unground barleycorn was sprinkled over the victim, altar and possibly the participants. Hair was cut from the victim’s head and burned on the altar. The victim was then killed with a blow from an ax, and its throat was cut—not usually by the priest or priestess, but by a particular official. Blood was collected in a bowl and splashed on the altar. The animal was then butchered, and the portion selected for the god was burned on the altar (apparently usually thigh bones wrapped in fat—worthless as food), while wine was simultaneously poured into the flames. The entrails were cooked separately and tasted first, then the remaining meat was cooked and eaten by the participants in a sacrificial feast at which the god was regarded as an honored guest.

The sacrifice took place in a sacred area, where the sacrificial meat often had to be consumed, although evidence suggests that sometimes the participants took home portions of sacrificial meat. The sacrifice was accompanied by music, and in post-Homeric times the entrails of the victim were examined for purposes of divination. In some local cults, women were banned from attending sacrifices. In purificatory sacrifices and those sacrifices designed to propitiate the gods, the whole animal (or other offering) was completely destroyed. The complete burning of a sacrifice is known as a holocaust; such a ritual was usually performed to propitiate gods of the underworld, although in times of crisis it was offered to any deity who was thought able to alleviate the problem. A hecatomb (hekatombe) was an offering of 100 oxen, but more often referred to a great public sacrifice, not necessarily of 100, nor of oxen.

Oath sacrifices were made to consecrate oaths. This was effectively a magical ritual, since oath takers made a conditional curse upon themselves that specified penalties if the oath was violated. Such a sacrifice is described in Homer’s Iliad, where those taking the oath first cut hair from the victims’ heads and invoked the relevant gods. They then stated the terms of the oath, cut the victims’ throat and poured libations of wine on the ground. Finally, they prayed to the gods and buried the victims or threw them into the sea. Although there are accounts of human sacrifice in Greek mythology, no definite evidence exists for human sacrifice, and the Greeks appear to have regarded the practice as barbaric. People were, though, expelled from cities as scapegoats (pharmakoi) during disasters such as plagues and famine. They were chosen from the poor and ugly. There is some evidence from Protogeometric to Classical times of ritual slaughter at the graveside, including the horses of the hearses; human sacrifice also possibly took place at the graveside.

Libations

Libations (offerings of a liquid as a sacrifice) were very common in honor of gods, heroes or the dead. Liquids were poured into a container and deposited in a sacred spot, or else poured on an altar, a rock or the ground. A distinction was made between a sponde, where a small part of the liquid was poured from a drinking vessel before the rest was drunk by the worshipper, and khoe, in which all the liquid was poured out. Spondai were particularly associated with solemnizing treaties and khoai with the dead. The most common liquid for libations was wine, quite often mixed with water (as normally drunk by the Greeks)

Water, milk, oil and honey were mainly used for specific rituals, and libations of oil, perfumes and ointments were smeared on sacred objects. A distinctive vessel called a phiale, usually of metal, was employed for pouring libations and was itself a common offering at religious sanctuaries. In the 5th century BC. in Athens, decorated flasks (lethykoi) containing oil were often deposited as grave goods and offerings.

Other Sacrificial Offerings

Apart from blood sacrifices of animals and libations, various other commodities were used as offerings to the gods. Incense, in the form of native herbs or expensive herbs imported from the East, were burnt on their own (as a modest sacrifice) or with other offerings. Fragrant substances such as incense, resin and spices were also burned on the altar or on braziers to neutralize the smell of burning flesh, hair and hoofs in animal sacrifices. Flowers were used as offerings, as well as to decorate sacrificial victims and adorn participants in rituals. Branches of trees, such as olive and laurel, were similarly used, and sometimes draped with fillets (decorative bands) of wool. All kinds of raw and cooked foods were used as offerings and in rituals. The panspermia (all-seeds) was an offering of a collection of different grains, and pots of cooked beans were deposited when an altar was set up and used as regular offerings. Pelanos was an offering made of flour mixed with liquids, and cakes in various shapes (often animals) were given as offerings. The “first fruits” (aparchai) of the harvest from fields and orchards were another popular offering. The idea also applied to meals, so that part of the meal was offered to the gods. 12

God is a Supreme Being who is independent therefore, neither the flesh nor the blood of the sacrificed animal nor the other offerings reach Him. He is the one who created everything, including those animals and other things which were supposedly being sacrificed in His name. So, sacrificing such things with such idiosyncratic and obscene methods create a lot of questions on the intellect of those so-called intelligentsia.

The physical act of sacrificing of the animals is just a ritual, and is just a sacred practice whereas the essence lies far beyond it and the spirit of it goes far beyond common human perception. Sacrifice, as portrayed by divine religions, and especially in Islam by Prophet Muhammad  is defined as giving up some of our own bounties, in order to strengthen ties of friendship and help those who are in need. It is to train us how to surrender ourselves to the will of Allah for the sake of serving humanity. We recognize that all blessings come from Allah, and we should open our heart and share those bounties with others. Secondly, it also symbolizes refraining from bad deeds and habits which would improve the spiritual condition of the sacrificer, and ensure betterment in the society which would also help him gain the approval of Allah.

is defined as giving up some of our own bounties, in order to strengthen ties of friendship and help those who are in need. It is to train us how to surrender ourselves to the will of Allah for the sake of serving humanity. We recognize that all blessings come from Allah, and we should open our heart and share those bounties with others. Secondly, it also symbolizes refraining from bad deeds and habits which would improve the spiritual condition of the sacrificer, and ensure betterment in the society which would also help him gain the approval of Allah.

Festivals

Practically, the religious worship of the Greeks consisted mainly in attendance on festivals which might be Pan-Hellenic, political, tribal, or peculiar to a guild or phratria. Each year brought round either one or two of the great panegyrics—the festivals of the entire Greek race at Olympia and Delphi, at Nemea and the Isthmus of Corinth. There were two great Ionic festivals annually, one at Delos, and the other at the Panionium near Mycale. Each state and city throughout Greece had its own special festivals, Dionysia, Eleusinia, Panatheiisea, Carneia, Hyakintlna, Apaturia, etc. Most of these were annual, and some lasted several days.

A Greek had no "Sunday"—no sacred day recurring at set intervals, on which his thoughts were bound to be directed to religion; but so long a time as a week scarcely ever passed without his calendar calling him to some sacred observance or other, some feast or ceremony, in honor of some god or goddess, or in commemoration of some event important in the history of mankind, or in that of his race, or of his city.

Accordingly, the Greek looked forward to his holy days as true holidays, and was pleased to combine duty with pleasure by taking his place in the procession, or the temple, or the theatre, to which inclination and religion alike called him. Thousands and thousands of people flocked to each of the great Pan-Hellenic gatherings, delighting in the splendor and excitement of the scene, in the gay dresses, the magnificent equipages, the races, and the games, the choric, and other contests. These festivals, as has been well observed, were considered important in Greek life, their periodical recurrence being expected with eagerness and greeted with joy. Similarly, though to a minor extent, each national or even tribal gathering was an occasion of enjoyment; cheerfulness, hilarity, sometimes an excessive exhilaration, prevailed; and the religion of the Greeks, in these its most striking and obvious manifestations was altogether bright, festive, and pleasurable. 13

Details of some of these festivals are given below:

The Spartan Karneia

The Dorian Karneia was celebrated in honor of Apollo Karneios (‘‘Apollo of the Ram’’), best known for precluding the waging of war and thus for causing the Spartans to arrive too late at the battle of Marathon. The festival of the Karneia lasted for nine days.’ Hesychius and other lexicographers provide us with further information. Five unmarried men from each tribe were allotted the liturgy, that is, official responsibility for laying on the festival, for a period of four years, the so-called Karneatai. It seems to have been some of these who took part in a kind of footrace under the name staphylodromoi, ‘‘grape-cluster runners.’’ They chased a single runner festooned with fillets of wool, and it was a good omen for the city if they catched him, a bad omen if they did not – though there was the let-out that he was meant to pray for the good of the city before or as he ran. Mixed dancing by boys and girls and above all choral song and dance also formed part of the program. A number of etiological myths are associated with the festival. The most influential in scholarship has been Pausanias’ story that the cult was established to propitiate Apollo for the murder of his Karnos by one of the Herakleidai, the Dorian descendants of Heracles, when they were conquering the Peloponnesos. 14

Hyacinthos

In Greek myth, Hyacinthos was a handsome Spartan youth loved by the god Apollo. While Apollo was teaching him how to throw the discus one day, the jealous West Wind god, Zephyros, sent the discus flying back into the young man’s skull. Hyacinthos lay dying, and from his blood there sprang the type of scarlet flower that the Greeks called the hyacinth. Hyacinthos was honored in a three-day early-summer festival throughout the Spartan countryside. His tomb was displayed at Apollo’s shrine at Amyclae, near Sparta. One ancient writer noted that Hyacinthos’s statue at Amyclae showed a bearded, mature man, not a youth. The name Hyacinthos was pre-Greek in origin, as indicated by its distinctive nth sound. Modern scholars believe that Hyacinthos’s cult dates back to pre-Greek times and that he was originally a local non-Greek god, associated with a local flower but not imagined as a young man and not yet associated with the Greek god Apollo. Sometime in the second millennium B.C.E., Hyacinthos was adapted to the religion of the conquering Greeks and was made into a human follower of Apollo. The element of romantic love between them may have been added later, after 600 B.C. 15

Panathenaia

A most prominent feature of Athena worship at Athens saw as a festival held every summer, the Panathenaea. 16 The Panathenaia, or ‘the festival of all the Athenians’ was the principal occasion for honoring Athena Polias, the patron goddess of the polis, and was held annually, a few weeks after midsummer, toward the end of the Hekatombaion, the first month in the Athenian calendar. As the Great Panathenaia, it was celebrated with special extravagance every four years. A smaller ceremony, known as the lesser Panathenaia, was held in the years between. By the classical period, the grander, penteteric (occurring every 5 years) version of the festival appears to have evolved in to one of the Greek world’s more impressive spectacles.

The ritual component was the core of the festival. This took place on 28th Hekatombaion. It began with a sacrificial procession along the Panathenaic Way, starting at the Diplyon Gate, at the northwest edge of the city, and proceeding through the Agora, up to the Acropolis. There, large number of victims were offered up to Athena at the Great Altar, and in the Arkhaios Neos, her small olive-wood idol, was draped in a new peplos (a rich outer robe). The sacrificial meat was later distributed by the deme, and all the Athenians present partook of the feasting that followed. Despite all the local significance of the festival’s ritual content, the organizers of the Panathenaia actively sought the participation of the outsiders. In particular, they aimed to attract those same luminaries of athletics and music who competed in the crown games at Olympia, Delphi, Isthmia, and Nemea. And to encourage leading athletics and musicians from all over Greece to take part in these contests, the organizers of the Panathenaia offered the added inducement of lavish prizes, from large sums of cash to decorated jars of olive oil. 17

Anthesteria

Anthesteria, a three-day-long festival held during the month of Anthesterion, was also known as the “more ancient Dionysia.” These three days of ritual centered on the racking of wine, propitiation of the dead, and issues of metempsychosis, including ceremonies alluding to transitional kingship. Anthesteria, an all-souls festival, had things in common with Celtic Beltane and Samhain rites. Indeed, the worshippers’ invitation to the dead to join in the ceremonies, combined with the air of consecration, eroticism, and topsy-turvy liberation, makes the Anthesteria seem like a fascinating combination of these two Celtic festivals.

The portion of the festival commonly begun on the 11th day of the month Anthesterion centered on the reopening of the huge, half-buried pithoi (earthenware crocks) in which the wine had overwintered in Athenian precincts, or the transport of smaller crocks from the countryside to Athens for use in the Athenian symposium. Libations were made directly from the newly opened crocks onto the ground in the memory of the ancestors and cthonic gods prior to any drinking or storage of the wine.

The word chous (singular of choe) refers to the ceremonial pitcher from which wine was customarily poured in libation to dead ancestors or cthonic Deities, and it is this word which was used to describe the second day of the Anthesteria proper. Considered by the ancients to be a “day of pollution,” Choës Day was the only day of the year when the Temple to Dionysos of the Swamps (Limnaios) was officially open to the public. Poetry, songs, and plays were performed in honor of Dionysos as Divine Bridegroom. A great deal of playacting and mummery went on during the entire Anthesteria festival; scholars note that wine lees were often used as face-paint by mummers.

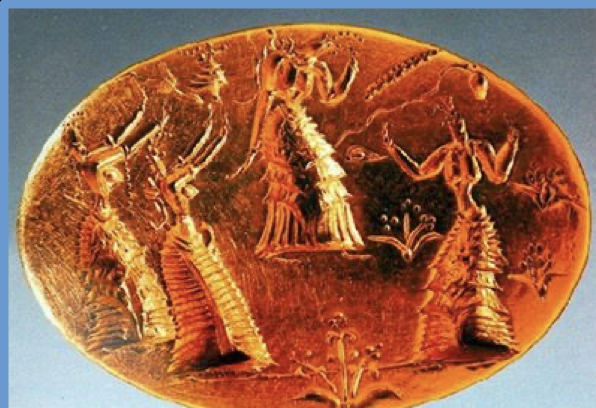

A ritual procession took place on the eve of Choes Day, originating from the Temple of Dionysos Limnaios and led by chanting, hymn-singing female worshippers, after the Neoptolemic meal of each individual had ended. This processional was made in anticipation of the “sacred marriage” of Dionysos with the Athenian Basilinna 18 , and the processional led from the Dionysian Temple sanctuary to the Boukoleon (“bull’s stable”), located in the central agora (“marketplace”) of Athens.

While the women of the city took part in the erotic events of Choes night within Athens, all the men of Athens were required to take part in the night-long symposium in the Temple en Limnais on the outskirts of the city.

A ritual offering anciently known as Chytroi, made to the spirits who rose into the living world when the wine pithoi (large storage container) were breached, was traditionally performed on the 13th day of Anthesterion. The Chytroi ritual marked a “return to normal” after the topsy-turvy, ghost-and erotica-filled days of the 11th and 12th. A customary offering of cooked grains and seeds — dedicated to the cthonic Deities and ancestors by being placed into naturally-occurring fissures in the earth — took place near the Temple of Dionysos, outside the city proper. Swings were set up over the half-buried pithoi outside the Temple of Dionysos, and maidens would play on the swings (aiora), a symbolic enactment of life following death following life in rhythmic and apparently endless progression.19

Aphrodisia

Festivals were celebrated in honor of Aphrodite, in a great number of towns in Greece, but particularly in the island of Cyprus. 20 Her most ancient temple was at Paphos, which was built by Aerias or Cinyras, in whose family the priestly dignity was hereditary. No bloody sacrifices were allowed to be offered to her, but only pure fire, flowers, and incense; and therefore, when Tacitus speaks of victims, we must either suppose, with Ernesti, that they were killed merely that the priest might inspect their intestines, or for the purpose of affording a feast to the persons present at the festival. At all events, however, the altar of the goddess was not allowed to be polluted with the blood of the victims, which were mostly he-goats. Mysteries were also celebrated at Paphos in honour of Aphrodite; and those who were initiated offered to the goddess a piece of money, and received in return a measure of salt and a phallus. In the mysteries themselves, they received instructions. A second or new Paphos had been built, according to tradition, after the Trojan war, by the Arcadian Agapenor; and, according to Strabo, men and women from other towns of the island assembled at New Paphos, and went in solemn procession to Old Paphos, a distance of sixty stadia (around 12 km); and the name of the priest of Aphrodite, seems to have originated in his heading this procession. 21

Brauronia

It was an Attic festival held every fifth year in the little town of Brauron, in honor of Artemis Brauronia. At Brauron, Orestes and Iphigenia on their return from Tauris were supposed to have landed and to have left the statue of the Tauric goddess. The festival was under the superintendence of ten; and the chief solemnity consisted in the circumstance that Attic girls between the ages of five and ten years, dressed in crocus-coloured garments, went in solemn procession to the sanctuary, where they were consecrated to the goddess. During this act, they sacrificed a goat, and the girls-performed a propitiatory rite in which they imitated bears. This rite may have simply arisen from the fact that the bear was sacred to Artemis, especially in Arcadia; but a tradition preserved in Suidas relates its origin as follows: In the Attic town of Phanidae a bear was kept, which was so tame that it was allowed to go about quite freely, and received its food from and among men. 22

The Eleusinian Mysteries

For almost two thousand years, the Eleusinian Mysteries, held in honor of Demeter and Persephone, were the most famous and influential religious cult in the ancient Greek world. Much is known about the more public aspects of the nine-day ceremonies, but a curtain of secrecy has always obscured what transpired once the initiates entered the walled sanctuary at Eleusis for the final day of the ceremonies.

One recorded feature that set the Eleusinian Mysteries apart from most other ancient mystery rites of the Mediterranean world was that first-time dedicants underwent a two-part initiation with an extended educational process provided between the two rites. Any person wanting to attend the greater Mystery rites at Eleusis had to first undergo a preliminary initiation known as the Agrai, or “lesser Mystery”, that was held in a precinct of Athens during the month of Anthesterion (approximately February 14 to March 12 on the modern calendar), a full seven months prior to the greater Mystery rite itself.

The greater Mysteries were a physically demanding, nine-day-long festival that began on the fourteenth day of Boedromeon, eight days before the Eleusinia proper, with the gathering of the Eleusinian epheboi — “(escorting) warriors” — and attendant priestesses at the sanctuary in Eleusis. In ritual procession, these individuals carried kalathoi (sacred baskets containing ritual implements and foodstuffs which would be needed by the mystai; it may be assumed that they were brought wholly or partially empty from Eleusis, and that the mystai filled them as part of the ceremonies leading up to the procession to Eleusis from Athens) along the Via Sacre to the Athenian Eleusinian. The Via Sacre, or Sacred Way — which ran a distance of roughly fourteen miles between Athens and Eleusis — was dotted with shrines commemorating the story of Demeter’s search for her daughter Persephone. Archeological evidence indicates that the shrines were built by epoptai in appreciation of the transformative power of the Mysteries.

Many of the preliminary rites held during the first few days, while the mystai were still gathered in Athens, seem to have involved acts of purification designed to spiritually prepare the initiates for the final night of Mysteries. For the entire nine days of the Eleusinia ceremony (Boedromeon 14-22), all dedicants observed abstinence-fasts as one form of purification. Some fasted from all food and water during the daylight hours, breaking the fast each evening, following the example of Demeter.

On the third day, Boedromeon 16th, each mystai bathed ritually in the sea with a piglet. It was believed in the ancient Greek world, as among some modern indigenous cultures, that the pig had the power to absorb evil and keep it away from humans.

On the sixth day, Boedromeon 19th, the dedicants, their associate mystagogoi (“those who guide the veiled”), and the epheboi all participated in another procession, now carrying the kalathoi of sacred items from Athens back to Eleusis. It is reported that a statue of the sacred youth Iacchos was carried in this procession by the Iacchogagos, a man specifically consecrated for this task. After the day-long trek from Athens to Eleusis, the dedicants would reach the Bridge of Rhiti, which spanned slender saline rivers that flowed into a salt lake near the Rharian Plain of Eleusis. Records suggest that the participants danced during all or part of their procession along the Sacred Way, and after a 14-mile journey, they would certainly have been exhausted.

Some Classics scholars, notably Paul François Foucart, have suggested that the eighth day of the Mysteries essentially involved a theatrical enactment of the story of Demeter and Persephone and that the sublime spiritual experience manifested at the climax of the Mysteries probably involved a play or other dramatized performance of the reunion of Mother and Daughter. Although initiates were forbidden to reveal exactly what happened at the climax of the Mysteries, they were only permitted to testify as to the impact of the experience. As Proculus observes: In the most sacred Mysteries before the scene of the mystic visions, there is terror infused over the minds of the Initiated. 23

Dionysia

Celebrations in the honor of Dionysus, were held in Athens in a special series of festivals, namely:

The Oschophoria:This was celebrated in the month of Pyauepsion (October to November), when the grapes were ripe. It was from the shoots of vine with grapes on them, which were borne in a race from the temple of Dionysus in Limuae, a southern suburb of Athens, to the sanctuary of Athene Sicras, in the harbour town of Phalerum. The bearers and runners were twenty youths of noble descent whose parents were still living, two being chosen from each of the ten tribes. The victor received a goblet containing a drink made of wine, cheese, meal, and honey, and an honorary place in the procession which followed the race. This procession, in which a chorus of singers was preceded by two youths in woman's clothing, marched from the temple of Athene to that of Dionysus. The festival was concluded by a sacrifice and a banquet.

The Smaller, or Rustic Dionysia:This feast was held in the month of Poseidon (December to January), at the first tasting of the new wine. It was celebrated, with much rude merriment, throughout the various country districts. The members of the different tribes first went in solemn processions to the altar of the god, on which a goat was offered in sacrifice. The sacrifice was followed by feasting and revelry, with abundance of jesting and mockery and dramatic improvisations. Out of these were developed the elements of the regular drama, for in the more prosperous villages, pieces—in most cases the same as had been played at the urban Dionysia—-were performed by itinerant troupes of actors. The festival lasted some days, one of its chief features being the Ascoliasmus, or bag-dance.

The Great Urban Dionysia:This festival was held at Athens for six days in the month of Elaphebolion (March to April) with great splendor, and attended by multitudes from the surrounding country and other parts of Greece. A solemn procession was formed, representing a train of Dionysiac revelers. Choruses of boys sang dithyrambs, and an old wooden statue of Dionysus, worshipped as the liberator of the land from the bondage of winter. The glory of this festival was the performance of the new tragedies, comedies, and satiric dramas, which took place, with lavish expenditure, on three consecutive days. In consequence of the immense number of citizens and strangers assembled, it was found convenient to take one of these six days for conferring public distinctions on meritorious persons, as in the case of the presentation of the golden crown to Demosthenes. 24

Olympics

The festival known as Olympics took place at the second or third full moon after the summer solstice, in the months of Apollonius and Parthenos respectively. The date was fixed by a cycle of eight years or ninety-nine months, the divergence between the year of twelve lunar months and the solar year being rectified by the insertion of three intercalary months, one in the first four years, two in the second. Thus, it fell alternately after forty-nine or fifty lunar months. The fourteenth day of the month seems to have been reckoned as the day of the full moon, though the actual full moon varied from the 14th to 15th. This day must, from the earliest time, have been the central day of the festival.

The Greek day was reckoned from sunset to sunset, and as Greek custom demanded that sacrifice to the Olympian gods needed to be offered in the morning, before mid-day, it follows that the great sacrifice to Zeus was offered on the morning after the full moon. The festival lasted five days. According to Herodotus, a historian of the fifth century, the five days festival was ordained by Heracles. It lasted five days in Pindar's time. Scholiasts of various dates, while affirming that it lasted five days, state that it began on the 10th or 11th and lasted till the 15th or 16th. The discrepancy may be due to the variation in the date of the full moon already noticed, more probably to the addition to the festival of one or more preliminary days necessitated in later times by the multiplication of competitions and religious ceremonies. To these days the preliminary business of the festival may have been transferred, but they were not reckoned as part of the actual festival.

These five days included sacrifices, sports, and feasts. Sacrifices and feasts, both private and public, formed part of each day's program, especially of the first and last days, which must have been largely, if not entirely, occupied by such ceremonies.

Plutarch definitely states that at Olympia the boy’s competitions took place before any of the men's. The foot-races all came on the same day, and probably before any other of the competitions for men. Wrestling, boxing, and the pankration (combination of wrestling and boxing) took place on the same day and in the same order. The race in armor was the last event of the whole program.

It is uncertain that when and where the victors were crowned. The only definite pronouncement on the point is that of a late scholiast, who states that the prizes were distributed on the sixteenth day.

The important of all the ceremonies was the sacrifice to Zeus on the morning after the full moon. The victors, the officials and the representatives of the different states, went in stately procession to the altar, where a hecatomb of oxen was sacrificed by the Eleans. This was the opportunity for the theoroi (sacred ambassadors) to display their magnificence, if there was any, and the wealth of their cities. 25

Theogamia

It was the anniversary of the marriage (gamos) of Zeus Teleios (authority, head of the gods’ family) and Hera Teleia, hence giving the month its name. Not much is known about this festival except that it was celebrated with great feasting. Because the sacred marriage was commemorated this month, the month became the ideal time to marry, perhaps because of the imminent arrival of spring. It’s also possible, but less likely, that the month was a marriage month first, and then became the appropriate date to celebrate the union of Hera and Zeus. 26

Burial

Some of the ancient Greek people used to ask themselves: What happens to us when we die? Our bodies decay, but is there a spirit, a soul, an essence of our personalities that survives us? And if so, how should we deal with the dead? How can we speak of them in terms we can relate to? Can we contact them – can they contact us? Their belief about survival after death varied widely and were not particularly consistent. Some Greeks denied any possibility of an afterlife, saying that the soul perished with the body. Others, such as Plato, believed the soul was immortal. Some believed that the spirit survived death, but as an insensate shell of its former self in a meaningless existence, lacking intelligence or understanding; others believed that the individual soul lived on after death with a recognizable personality.

Whether the average Greek believed in the soul or not, he at least believed that certain rites were due to the dead. Death was a passage to be marked with ceremony, and despite the lack of a universal doctrine about the nature of the soul, actual funeral and mourning customs in ancient Greece were relatively uniform. The Greeks practiced both inhumation and cremation, though the popularity of one method or the other varied over place and time. The manner of disposal was perhaps less important than the accompanying rites performed over the body. Ninth-century Greek geometric vases left as grave goods in the Kerameikos depict mourning rituals such as a body lying on a bier surrounded by women tearing their hair, or a body being carried out for burial.

A typical Greek burial ritual included several stages, in which the women of the family played a prominent role. First came the ‘laying out’ of the corpse, or prosthesis, during which the women would wash the body, anoint it, dress it by wrapping it in cloth, and lay it on a bier for the family to perform the traditional lament and pay their last respects. Once coinage became widespread, in the sixth century and later, a coin was placed in the mouth or hand of the deceased to symbolize payment for Charon, the mythological ferryman who rowed the dead across the river Styx, the final boundary between the living and the dead. After the prosthesis, which lasted one day, the body would then be transferred at night to its burial site in a formal but quiet procession, the ekphora . 27 ] At the cremation or burial site the family would make offerings of food, wine, olive oil, and various household possessions – such as weapons for the men or jewelry for the women – burning or burying them with the body, the idea being, at least in part, that the dead person might have use for these items in the afterlife.

The funeral would end with a family banquet in honor of the dead, the perideipnon, or ‘‘feast around,’’ though the banquet was held not at the gravesite but back at the family home. The funeral feast usually involved animal sacrifices. This sequence of ceremonies had its origins at least as far back as the Bronze Age, and as far as literary and archaeological evidence admits, the rituals changed little over the entire course of Greek history. 28

The law of Athens required anyone who chanced upon a corpse, to at least to cover it with earth. Even if one had entertained the bitterest enmity towards the deceased while he lived, still, all remembrance of the feud was to be thrown aside, when death intervened and due attention was shown to the dead.

There were some cases where burial was forbidden. It was the severest aggravation of the penalty of execution for a crime that the body of the criminal was denied interment. Such corpses, both at Athens and Sparta, were cast with the halter and their garments in to a pit in an allotted quarter of the city where the flesh might decay or be eaten by carrion birds. 29

Religion was always free in Greece and no man was forced to worship. Consequently, every type and kind of cult developed freely. To the Greek religion was observance, ritual, and awe combined, with lurking in the background great forces whose action revolved on mighty wheels. What is fated, fixed, or destined—it is seldom made into a personification—is at the back of all action. Men must see to it that the smaller wheels of their own actions revolve in harmony with the greater mechanism otherwise the smaller will be shattered. 30

Since the Greeks had no religious text, their beliefs and practices were mainly composed of mythical stories which differed from place to place and were insensible in their nature. The people (priests/priestesses) who conducted the religious activities were considered as a mediator between the gods and men, and were given special respect and honor due to their misguidance. The gods were believed to be a multigenerational family, could indulge in immoral activities and interfere in human affairs. Still, the Greeks worshipped them because they believed that the gods welcomed it, and also responded to certain acts of piety.

Majority of the religious festivals, prayers and sacrifices of ancient Greece involved drinking, erotic acts, and display of obscene acts. These acts were done in the name of religion but in reality, had no connection to it, but were rather connected to the Devil.

All these so-called religious rites were a perfect recipe for social violence, rapes, and obscenity which would end up in dividing the society whereas pure religious rituals unite the society. A brilliant example can be seen in the case of Ancient Arabia. Before the Advent of Prophet Muhammad  similar polytheistic, obscene and fetish rituals were observed over there as well. Cruelty was prevalent and the people were in a pitiable condition. He reiterated the religion which was preached by many prophets before him. When the people accepted the divine message, he gave them festivals like Eid-al-Fitr, Eid-al-Adha and many more which were pure in nature. Secondly these festivals ensured that the poor benefited the most and the society remained united and prospered. Such festivals were not seen in any of the other non-revealed religions of the world.

similar polytheistic, obscene and fetish rituals were observed over there as well. Cruelty was prevalent and the people were in a pitiable condition. He reiterated the religion which was preached by many prophets before him. When the people accepted the divine message, he gave them festivals like Eid-al-Fitr, Eid-al-Adha and many more which were pure in nature. Secondly these festivals ensured that the poor benefited the most and the society remained united and prospered. Such festivals were not seen in any of the other non-revealed religions of the world.

- 1 Hemingway, Colette, and Sean Hemingway (2000), “Greek Gods and Religious Practices.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grlg/ hd_grlg.htm : Retrieved: 20-03-2017

- 2 Wikipedia (The Free Encyclopedia) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Ancient_Greek_temples: Retrieved: 03-05-2017

- 3 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA Pg. 370.

- 4 Jane Ellen Harrison (1913), The Religion of Ancient Greece, Constable & Company Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 37-38.

- 5 Elisabeth Sinclair Holderman (1913), A Study of the Greek Priestess, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago Illinois, USA, Pg. 1-3.

- 6 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA Pg. 370.

- 7 George Rawlinson (1885), The Religions of the Ancient World, John B. Alden Publisher, New York, USA, Pg. 152-154.

- 8 Kore, plural korai, was a type of freestanding statue of a maiden—the female counterpart of the kouros, or standing youth—that appeared with the beginning of Greek monumental sculpture in about 660 BC and remained to the end of the Archaic period in about 500 BC. [Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/art/kore-Greek-sculpture : Retrieved: 15-04-19

- 9 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 370-372.

- 10 David Sacks, Revised by Lisa R. Brody (2005), Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World, (Revised Edition), Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 297.

- 11 Hecate was a popular and ubiquitous goddess from the time of Hesiod until late antiquity. Unknown in Homer and harmless in Hesiod, she emerges by the 5th century as a sinister divine figure associated with magic and witchcraft, lunar lore and creatures of the night, dog sacrifices and illuminated cakes, as well as doorways and crossroads. (Oxford Classical Dictionary: http://oxfordre.com/classics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.001.0001/acrefore-9780199381135-e-2957: Retrieved: 15-04-19)

- 12 Lesley Adkins & Roy A. Adkins (2005), Handbook to the Life in Ancient Greece, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 371-373.

- 13 George Rawlinson (1885), The Religions of the Ancient World, John B. Alden, Publisher, New York, USA, Pg. 152-153.

- 14 Daniel Ogden (2007), A Companion to Greek Religion, Blackwell Publishing, New Jersey, USA, Pg. 193.

- 15 David Sacks, Revised by Lisa R. Brody (2005), Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World, (Revised Edition), Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, PG. 164-165.

- 16 George Willis Botsford (1926), Hellenic History, The Macmillan Company, New York, USA, Pg. 141.

- 17 Greg Anderson (2003), The Athenian Experiment: Building an Imagined Political Community in Ancient Attica, 508-490 BC., The University of Michigan Press, Michigan, USA, Pg. 158-159.

- 18 Basilinna was a ceremonial priestess-queen chosen to rule with her husband, a ceremonial king or Archon Basileus, for a year. [Barbara Goff (2004), Citizen Bacchae: Women’s Ritual Practice in Ancient Greece, University of California Press, Berkeley, USA, Pg. 38.

- 19 Rosemarie Taylor-Perry (2003), The God Who Comes: The Dionysian Mysteries Revealed, Algora Publishing, New York, USA, Pg. 69-74.

- 20 William Smith (1875), A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, U.K., Pg. 31-32.

- 21 Ibid, Pg. 102.

- 22 Harry Thurston Peck (1898), Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, Harper and Brothers, New York, USA, Pg. 221.

- 23 Rosemarie Taylor-Perry (2003), The God Who Comes: The Dionysian Mysteries Revealed, Algora Publishing, New York, USA, Pg. 103-113.

- 24 Harry Thurston Peck (1898), Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, Harper and Brothers, New York, USA, Pg. 520-521.

- 25 E. Norman Gardener (1910), Greek Athletic Sports and Festivals, Macmillan and Co. Limited, London, U.K., Pg. 194-207.

- 26 H. W. Parke (1977), Festivals of the Athenians, Thames and Hudson Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 104.

- 27 Ekphora is a public, interactive ritual. On the level of death ceremonial it refers to carrying the body out accompanied by mourners and torches. [F. P Retief (2006), Burial Customs, The Afterlife and Pollution, Acta Theologica, Makhanda, South Africa, Pg. 53

- 28 Daniel Ogden (2007), A Companion to Greek Religion, Blackwell Publishing, New Jersey, USA, Pg. 86-88.

- 29 Frank P. Graves, A.B (1891), The Burial Customs of the Ancient Greeks, Roche & Hawkins, Brooklyn, USA, Pg. 10-13.

- 30 Stanley Cason (1922), Ancient Greece, Oxford University Press, London, U.K., Pg. 62-65.