- Home

- About Us

- Contribute

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Contact Us

Geography and Climate of Arabia

(Mufti. Shah Rafi Uddin Hamdani & Dr. Imran Khan)

Arabia is the largest peninsula on earth, 1 being one third of the size of Europe. 2 It lies between latitudes 13° and 32° N and longitudes 35° and 60° E and is considered as a part of the great desert belt, which stretches from the Atlantic Ocean, near the coast of north western Africa, to the Thar Desert of North Western India. 3 It is formed of crystalline rock that developed at the same time as the Alps did. 4

As a peninsula, it is enclosed on three sides by water, the Red Sea to the West, the Arabian (Persian) Gulf to the East and the Arabian Sea to the South. It forms the Southwestern wing of Asia, connected to Africa by the Desert of Sinai and Egypt. 5 The shape of Arabian Peninsula is like an irregular rectangle. On the North it is bound by Palestine, the Syrian Desert and parts of Iraq. The valley of Mesopotamia (the valley between Euphrates and Tigris) and the Persian Gulf are located on the East while the Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Adan are positioned on its South. 6 The Arabian Sea, which is an extension of the Indian Ocean, is also at its South. The Red Sea and Sinai Desert are found on its West. 7 The kingdom of Al-Hirah was located in its East. 8

Geographically, the peninsula and the Syrian Desert merge in the north with no clear line of demarcation. An imaginary line from the Gulf of Al-‘Aqaba in the West to the Tigris-Euphrates valley (Mesopotamia) in the East may be considered as the Northern edge of Arabia. 9 Some consider the northern boundaries of Saudi Arabia and of Kuwait as the marking limits of Arabia.

The total area of Arabian Peninsula is about 1,200,000 square miles (almost 3,100,000 square kilometers). The length of the Arabian peninsula bordering the Red Sea is approximately 1,200 miles (1,900 km) while the maximum breadth, from Yemen to Oman is about 1,300 miles (2100 Km). The island of Socotra which is located about 200 miles southeast of the mainland in the Indian Ocean, has strong ethnographic links to Arabia. Politically it is considered a part of Yemen. In contemporary times, Arabia is divided in to different states or political splits among them, the largest political division of the region is Saudi Arabia; which is followed in terms of size, by Yemen, Oman, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar, and Bahrain. 10

Arabia in the Ice Age

At the time when Europe lay dry and icy below the glaciers of the Ice Age, Arabia was a territory covered by forests and pastures, and irrigated by three mighty rivers. Then as the earth spun over on its axis as well as its crust hurled, rising here and dwindling there. Resultantly, the seasons and the climates altered then the ice melted and Europe roused to life but the Arabian region converted in to a desert. The rainfall became so less that the rivers dried up; the jungles faded away and the sand swept over the meadows. 11 Evidences have been found that the North Arabian Desert was once a fertile and well-watered land and sustained a large semi-nomadic population. Climatic conditions in ancient times, must have shaped great regions, having an amiable temperature and an ample supply of water. However, today Arabia - except in certain oases and along the bordering region - can only support a nomadic or semi-nomadic inhabitation. 12

Topography of Arabia

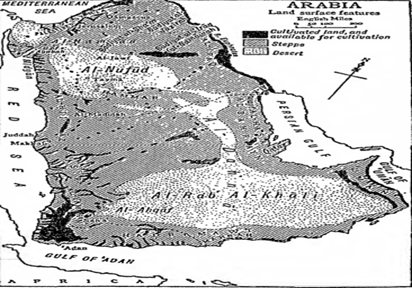

According to the physical features, the Arabian Peninsula has been divided in to 3 regions:

- Deserts of Arabia.

- Western and Southern coasts of Arabia including their Mountain ranges and plains. It includes Hijaz, Tihama, Asir Mountain, Yemen, Hadramaut, Dhuffaar and Oman.

- Central Plateau of Arabia including Eastern shores and planes of Peninsula. This region includes Najd, Yamamah, Qusaim, Tay Mountain, Al-Ahsa, Qatar, Kuwait and Bahrain. 13

Arabian Deserts

Approximately, 450,000 Square miles of Arabia consist of pure desert 14 which include Al-Rub Al-Khali, Al-Nafud, Al-Dahna and Al-Badiyat Al-Sham.

Al-Rub Al-Khali

The biggest desert of Arabia is Al-Rub Al-Khali which extends from the Southeastern part of Arabia to the central part of Arabia, 15 stretching over an area of 660,000 square kilometers. 16 It is one of the largest sandy deserts in the world. The latest generation of public-release satellite imagery exposes spatially varied dune patterns categorized by a diverse range of dune sorts. Their orientation, scale and morphology change scientifically from central to peripheral dune-field zones. 17 The large sand dunes of Rub Al-Khali are measured to range from 50-250 m in height. 18

Most of the Rub Al-Khali receives less than 50 mm rainfall, while some areas, even less than 25mm on average. Thus, most parts of Rub Al-Khali are waterless, unfertile, desolate regions and are lightly inhabited by Bedouin tribes, and the occasional visitors like oil explorers. 19 Water wells are very rare and most are even hundreds of miles away from each other. Sand storms are common, and if someone accidentally gets stuck in it, its difficult to make it out alive. 20

Many important regions of Arabia are located on different sides of Al-Rub Al-Khali. On the northern side of this vast desert is Al-Ahsa or Bahrain, Oman is located in the Southeast, while Hadhramaut and Mahra are positioned in the South. Sana'a, the famous city of Yemen is located in the Southwest of Al-Rub Al-Khali. It lies on the coast of the Arabian Sea and the Red Sea. When

Al-Nafud

Al-Nafud is located in the north-western part of Arabia. It is the second largest desert of Arabia, located 800 miles away from Al-Rub Al-Khali in the north. Al-Nafud consists of a large desert region and several small sections. The large one is called Al-Nafud Al-Kubra while the minor sections include Al-Nafud Al-Batra, Al-Nafud Qanifaza, Al-Nafud Al-Sir and Al-Nafud Al-Shaqiqah. It only rains during the winter season and allows the desert plants to grow. 22 Al-Nufud, is a land of white or reddish sand which blows into high sand banks or mounds and covers a massive area in North Arabia. It is a waterless dry land except for occasional oasis. 23

Al-Dahna

Al-Dahna, extends southward from the north-eastern edge of Al-Nafud to the north-western borders of Al-Rub Al-Khali (the Empty Quarter), thus, it connects the great deserts of Arabia. It contains seven main sand ridges, which are detached from one another by grasslands. 24 Al-Dahna literally means, the red land and it has been called Al-Dahna because the desert has a reddish sand which spreads from the great Nufud in the north to Al-Rub Al-Khali in the south, unfolding a great curve to the southeast and widening a distance of over six hundred miles. Hence, it is often referred to as an arc of reddish sand. Its western part is occasionally known as Al-Ahqaf or the dune land. On older maps Al-Dahna is generally indicated as a part of Al-Rub Al-Khali. Al-Dahna receives periodic rains and blooms in to grazing fields and remains attractive to the Bedouins and their livestock for several months a year. However, during the summer season the region becomes desolate. 25

Al-Badiyat Al-Sham (The Syrian Desert)

Al-Badiyat Al-Sham or Syrian Desert extends northward from the Arabian Peninsula and covers much of northern modern Saudi Arabia, eastern areas of Jordan, southern part of Syria, and western Iraq. It is an arid wilderness which receives on average, less than 5 inches (125 mm) of rainfall annually. The region is largely covered with mountains made by cooled ancient lava which made an almost impassable fence between the populated regions of the Levant and the valley of Mesopotamia until contemporary times. The southern sector of the desert, which is usually known as Al-Ḥammad, is populated by numerous roaming clans and breeders of Arabian horses. 26

Wadi Sirhan is a famous valley located in this region which serves as a major trade and transportation route between Syria and Arabia from ancient times. There are oases on both the sides of valley, where different human inhabitations are located. In ancient times, whiling travelling on this route, Arab-Syrian caravans would stay in these valleys. There are high mountain ranges on eastern, western and northern sides of Badiyat Al-Sham (the Syrian Desert). Khalid ibn Walid crossed this desert in five days with a complete Muslim army to join forces in Syria. The sand in Badiyat Al-Sham is whitish rather than reddish. 27

Al-Harrah (Volcanos)

A surface of ridged and fissured magmas covering sandstone is called Al-Harrah (الحرّۃ), in Arabic. A large number of volcanic zones are found in the western and central areas of Arabian Peninsula and spread north as far as eastern Hawran. Around thirty of such Harrahs are listed by geographers. The last volcanic eruption took place in 1256 C.E. 28

Mountain Ranges of Arabia

Arabia is bordered in the south and the west by mountain ranges of varying altitudes, reaching around 14,000 feet in the south and about 10,000 feet in the north. Starting from Hadramaut in the south, these mountain ranges run nearly parallel to the shoreline, through Yemen, Asir and all along Hijaz as well as the towns of Makkah and Ta’if and connect to the mountain ranges in the Sinai, Palestine, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon. In the eastern region, there are small mountain ranges, particularly in Oman, the Al-Akhdar Mountain rise to a height of around 10,000 feet. On the western side of Peninsula, the mountains escalate rather steeply, separating a narrow shoreline belt of plain and relatively fertile lands. The mountainous region in the west averages an altitude of about 4000 feet. 29

Arabian Plateau

The main orographic feature of the Arabian Peninsula is the great plateau of Arabia, with its high southwestern edge directing the Red Sea and its long mild slope to the northeast to the plains of Mesopotamia as well as the depths of the Persian Gulf. The Arabian Plateau, both at its eastern and western ends, is edged by orographic landscapes of a diverse character. To the east, occupying the lands of Oman, are wrinkle ranges supposed to be physically linked with those of Southern Persia. The Mountain systems of Syria and Palestine are located in the West of Peninsula, which form an essential feature of the landscape. 30

Climate of Arabia

Arabia is one of the hottest and driest regions of the world. 31 The Tropic of Cancer passes across the middle of the Red Sea and over the middle of the Arabian Plateau to Muscat on the Gulf of Oman. Arabia lies in the continuation of the extra-tropical high-pressure belt of the Sahara while Palestine, Syria and Iraq lie in the continuation of the Mediterranean belt. 32 Therefore, the climates of all these localities are relatively extreme as compared to many other parts of the world. It is very hot throughout the summer, and quite cold in the winter season. In winters, the temperature in some places in the north and south drops far below zero degree centigrade. 33

In summer, Arabia lies within the maximum heat zone of the world. Average temperatures in July at places surpasses 95-degree Fahrenheit. The heat on the shores of Arabia becomes rises to more than the other parts of the region because of the humid air caused by the evaporation from the Persian Gulf or the landlocked Red Sea. 34

Since Arabia is located at the arid subtropical zone, the key route of the jet stream which regulates the channel of atmospheric depressions lies north of the Pontic Mountains of Turkey during the summer season. While during winter season, this route of jet streams covers the northern Arabian Gulf and moves southwards. Only the Arabian Sea coastline to a limited extent, benefits from the track of the monsoon. 35 The precipitation is low and inconsistent. Thus, human settlements are only limited to areas with permanent water springs, oases or the areas where irrigation is possible.

Frequent cyclones, with characteristics of the westerly wind belt are common in winter. They deposit their moisture on Lebanon and the hills of Palestine, or on the second rampart shaped by Anti Lebanon Mountain. When the winds have crossed these two ramparts, they become dry so, the Syrian Desert and the Northern part of the Arabian Desert also becomes dry. The whole strip is rainless and faces extreme hot weather in summer. Droughts occur in Arabia due to its position in the high-pressure belt, as well as its lofty surrounding rim that seizes any moisture and does not let it reach the interior. 36

Thus, the mountain ranges of south and north hinder the monsoon rains from the Indian Ocean and during the winter, the rains from the Atlantic and the Mediterranean Sea, from entering the inner land. Hence, rainfall is usually very light in most parts, but there are occasional heavy rainstorms at many places including Makkah, Madinah, Ta’if and Riyadh. The existence of numerous valleys or streambeds indicates that in ancient times, the land was possibly more humid and there was plenty of rainfall in the region. 37 After these rains, the tough pastoral plants of the desert appear. In northern Hijaz, the remote oases, the biggest one of them covering an area of some ten square miles, are the only sustenance of settled life because five sixths of the population of Hijaz was nomadic. 38

Inhabitants of Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, has been populated from the earliest pre-historic period down to contemporary times. 39 Historians have divided the dwellers of Arabia into two groups, ‘the inhabitants of the cities’ and ‘the inhabitants of the desert’. 40 The Bedouins or 'inhabitants of the desert' were nomadic tribes, who wandered from place to place in search of enough vegetation to keep their herd of sheep and goats alive, 41 while the inhabitants of the cities settled in one area as they were familiar with how to till the lands and cultivate corn. They also had internal trade and exports with other countries as well and thus, can be classified as more sophisticated and cultured than the Bedouins. 42 Makkah is considered to be the oldest city in Arabia, whose ancient name was Becca or Baca. 43

Characteristics of Bedouin life

Nomads had no desire for settled life as they had perpetual movement in pursuit of pasture and fulfilment of their current desires. The basic unit of life, in the desert was not a state but a tribe. 44 The tribe did not generally acknowledge private property-owning, but exercised communal rights over pastures, water sources, etc. Even the flocks were at times, shared property of the tribe and only portable objects were subject to private ownership. 45

Arabic Bedouins, because of their constant movement, had no idea of any universal law or any general political order. They never accepted anything against total freedom of the individual, family and for the tribe as a whole. Settled people, on the other hand, agreed to give away lot of their autonomy in exchange for peace, security and the prosperity, whether to the group or to an absolute ruler but desert men never gave away their freedom for such gains. 46

In the Arabian Bedouin society, a group was considered as a social unit rather than an individual. The group was bonded together, apparently by the necessity for self-protection against the adversities and perils of desert life but internally by the blood-tie of origin in the male line which was the basic communal bond. 47

An Arab Bedouin did not compromise on the principles of honor and integrity demanded by the free life of desert. Therefore, the desert people have never agreed to any injustice inflicted upon them but resisted with all their strength. If they were unable to get rid of the injustice forced upon them, they would give up the area and move out into the other regions of the desert. These circumstances of desert life led to the cultivation and evolution of the merits and virtues of bravery, hospitality, neighbor protection, mutual assistance, magnanimity and benevolence. So, these qualities are stronger and more popular in deserts and villages while they are rarer and weaker in towns and cities. 48

The livelihood of an Arab Bedouin tribe was dependent on their flocks, herds and on invading adjacent settled areas and passing by caravans. They usually maintained a system of joint raiding by which, commodities plundered from the settled lands reached their people via the tribes on the borders to those who were located on the interior region of the desert. 49

Geographical Importance of the Region

The Arabian Peninsula has always sustained a unique position in the region because of its geographical location. It was always inaccessible to foreigners and invaders because of the deserts and arid nature, which allowed its people to live with complete liberty over the ages, regardless of the presence of two adjacent mighty empires. Thus, natural isolation and its size protected Arabian lands, against foreign invasions. 50 This geographical isolation allowed Arabs, primarily the nomads, not only biologically but linguistically, psychologically and socially the best representatives of the Semitic race. Thus, the monotonous consistency of desert life preserved their ethnic purity for centuries. 51

Arabia’s external setting and strategic location turned it to be the midpoint of the known continents of the ancient world, which resulted in the building of sea and land links with other nations. Hence, it had become the center for trade, culture, religion and art. 52

Hence, the Holy Prophet  was also sent to Arabia, but as a blessing for all creation. He was sent there for a number of reasons. Firstly, the people of Arabia had neither become subjects of any foreign power nor had they been ruled by any country. Secondly, no language of any region had achieved such perfection as Arabic, which surpassed other languages in power of expression. Thirdly, it was the center of trade which lies at the juncture of Europe, Asia and Africa. Fourthly, if Prophet Muhammad

was also sent to Arabia, but as a blessing for all creation. He was sent there for a number of reasons. Firstly, the people of Arabia had neither become subjects of any foreign power nor had they been ruled by any country. Secondly, no language of any region had achieved such perfection as Arabic, which surpassed other languages in power of expression. Thirdly, it was the center of trade which lies at the juncture of Europe, Asia and Africa. Fourthly, if Prophet Muhammad  had been sent to any other country except Arabia, the message could also have been attributed to other ancient traditions of the chosen country; hence he was sent to the arid region of Arabia which was neither conquered by any other superpower nor was in a united condition.

had been sent to any other country except Arabia, the message could also have been attributed to other ancient traditions of the chosen country; hence he was sent to the arid region of Arabia which was neither conquered by any other superpower nor was in a united condition.

- 1 R. W. McColl (2005), Encyclopedia of World Geography, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Vol. 1, Pg. 710.

- 2 Muhammad Mohar Ali (1997), Sirat Al-Nabi and the Orientalists, King Fahd Complex, Madinah, Saudi Arabia, Vol. 1, Pg. 29.

- 3 Abdulrahman Alsharhan, Zeinelabidin S. Rizk et al. (2001), Hydrogeology of an Arid Region: The Arabian Gulf and Adjoining Areas, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, Pg. 7.

- 4 R. W. McColl (2005), Encyclopedia of World Geography, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 710.

- 5 Muhammad Mohar Ali (1997), Sirat Al-Nabi and the Orientalists, King Fahd Complex, Madinah, Saudi Arabia, Vol. 1, Pg. 29.

- 6 Husein Haykal (1976), The Life of Muhammad ﷺ (Translated by Ismail Razi Al-Faruqi), Islamic Book Trust, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, Pg. 8.

- 7 Safi Al-Rahman Al-Mubarakpuri (2010), Al-Raheeq Al-Makhtum, Dar ibn Hazam, Beirut, Lebanon, Pg. 21.

- 8 Husein Haykal (1976), The Life of Muhammad ﷺ (Translated by Ismail Razi Al-Faruqi), Islamic Book Trust, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, Pg. 8-9.

- 9 Muhammad Mohar Ali (1997), Sirat Al-Nabi and the Orientalists, King Fahd Complex, Madinah, Saudi Arabia, Vol. 1, Pg. 29

- 10 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online): https://www.britannica.com/place/Arabia-peninsula-Asia: : Retrieved: 20-03-20121.

- 11 H. C. Armstrong (1934), Lord of Arabia, Arthur Barker Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 11.

- 12 Henry Field (1932), The Ancient and Modern Inhabitants of Arabia, The Open Court, London, U.K., Vol. 46, Issue. 12, Article 4., Pg. 848-849.

- 13 Muhammad Raby Hasni Nadvi (1962), Geographia-e-Mumalik-e-Islamiyah, Maktabah Dar Al-Uloom Nadva Al-Ulma, Lucknow, India, Pg. 9.

- 14 Akbar Shah Najeebabadi (2000), The History of Islam, Darussalam, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Vol. 1, Pg. 52.

- 15 Muhammad Mohar Ali (1997), Sirat Al-Nabi and the Orientalists, King Fahd Complex, Madinah, Saudi Arabia, Vol. 1, Pg. 29-30.

- 16 Mohammed A. Al-Masrahy & Nigel P. Mountney (2013), Remote Sensing of Spatial Variability in Aeolian Dune and Inter Dune Morphology in the Rub’ Al-Khali, Saudi Arabia, School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, Leeds, U.K., Pg. 1.

- 17 Ibid.

- 18 Arun Kumar and Mahmoud M. Abdullah (2011), An Overview of Origin, Morphology and Distribution of Desert Forms, Sabkhas and Playas of the Rub’ Al-Khali Desert of the Southern Arabian Peninsula, Earth Science India, India, Vol. 4, Issue: 3, Pg. 105.

- 19 H. Stewart Edgell (2006), Arabian Deserts: Nature, Origin and Evolution, Springer, Netherlands, Pg. IXVI.

- 20 Muhammad Raby Hasni Nadvi (1962), Geographia-e-Mumalik-e-Islamiyah, Maktabah Dar Al-Uloom Nadva Al-Ulma, Lucknow, India, Pg. 23-24.

- 21 Akbar Shah Najeebabadi (2000), The History of Islam, Darussalam, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Vol. 1, Pg. 52.

- 22 Muhammad Raby Hasni Nadvi (1962), Geographia-e-Mumalik-e-Islamiyah, Maktabah Dar Al-Uloom Nadva Al-Ulma, Lucknow, India, Pg. 26.

- 23 Phillip K. Hitti (1970), History of the Arabs, Macmillan Education Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 15.

- 24 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online): https://www.britannica.com/place/Al-Dahna: Retrieved: 2021-06-07.

- 25 Phillip K. Hitti (1970), History of the Arabs, Macmillan Education Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 15.

- 26 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online): https://www.britannica.com/place/Syrian-Desert: Retrieved: 2021-06-07.

- 27 Muhammad Raby Hasni Nadvi (1962), Geographia-e-Mumalik-e-Islamiyah, Maktabah Dar Al-Uloom Nadva Al-Ulma, Lucknow, India, Pg. 29-31.

- 28 Phillip K. Hitti (1970), History of the Arabs, Macmillan Education Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 17.

- 29 Muhammad Mohar Ali (1997), Sirat Al-Nabi and the Orientalists, King Fahd Complex, Madinah, Saudi Arabia, Vol. 1, Pg. 29.

- 30 L. Dudley Stamp (1946), Asia a Regional and Economic Geography, Methuen & Co. Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 106-107.

- 31 Phillip K. Hitti (1970), History of the Arabs, Macmillan Education Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 17.

- 32 L. Dudley Stamp (1946), Asia a Regional and Economic Geography, Methuen & Co. Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 109.

- 33 Muhammad Mohar Ali (1997), Sirat Al-Nabi and the Orientalists, King Fahd Complex, Madinah, Saudi Arabia, Vol. 1, Pg. 30.

- 34 L. Dudley Stamp (1946), Asia a Regional and Economic Geography, Methuen & Co. Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 110.

- 35 Abdulrahman Alsharhan and Zeinelabidin S. Rizk et al. (2001), Hydrogeology of an Arid Region: The Arabian Gulf and Adjoining Areas, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, Pg. 18.

- 36 L. Dudley Stamp (1946), Asia a Regional and Economic Geography, Methuen & Co. Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 109.

- 37 Muhammad Mohar Ali (1997), Sirat Al-Nabi and the Orientalists, King Fahd Complex, Madinah, Saudi Arabia, Vol. 1, Pg. 29.

- 38 Phillip K. Hitti (1970), History of the Arabs, Macmillan Education Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 17-18.

- 39 Henry Field (1932), The Ancient and Modern Inhabitants of Arabia, The Open Court, London, U.K., Vol. 46, Issue. 12, Article 4. Pg. 847.

- 40 K. Ali (1970), A study of Islamic History, Ali Publications, Dhaka, Bangladesh, Pg. 16.

- 41 Majid Ali Khan (1983), Muhammad (ﷺ) the Final Messenger, Sh. Muhammad Ashraf Publishers, Lahore, Pakistan, Pg. 42.

- 42 K. Ali (1970), A Study of Islamic History, Ali Publications, Dhaka, Bangladesh, Pg. 16.

- 43 Holy Quran, Al-Imran (The Family of Imran) 3: 96.

- 44 Husein Haykal (1976), The Life of Muhammad ﷺ (Translated by Ismail Razi Al-Faruqi), Islamic Book Trust, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, Pg. 15.

- 45 Bernard Lewis (1966), The Arabs in History, Harper & Row Publishers, New York, U.S.A., Pg. 29

- 46 Husein Haykal (1976), The Life of Muhammad ﷺ (Translated by: Ismail Razi Al-Faruqi), Islamic Book Trust, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, Pg. 15.

- 47 Bernard Lewis (1966), The Arabs in History, Harper & Row Publishers, New York, U.S.A., Pg. 29

- 48 Husein Haykal (1976), The Life of Muhammad ﷺ (Translated by: Ismail Razi Al-Faruqi), Islamic Book Trust, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, Pg. 15-16.

- 49 Bernard Lewis (1966), The Arabs in History, Harper & Row Publishers, New York, U.S.A., Pg. 29.

- 50 Safi Al-Rahman Al-Mubarakpuri (2010), Al-Raheeq Al-Makhtum, Dar ibn Hazam, Beirut, Lebanon, Pg. 21-22.

- 51 Phillip K. Hitti (1970), History of the Arabs, Macmillan Education Ltd., London, U.K., Pg. 8.

- 52 Safi Al-Rahman Al-Mubarakpuri (2010), Al-Raheeq Al-Makhtum, Dar ibn Hazam, Beirut, Lebanon, Pg. 21-22.